Book looking at legal side of pro wrestling a long time coming

Working with SlamWrestling.net gives me the opportunity to read and review books. It’s one of my favorite parts of the gig, since I love reading and learning about how one of my favorite forms of entertainment works.

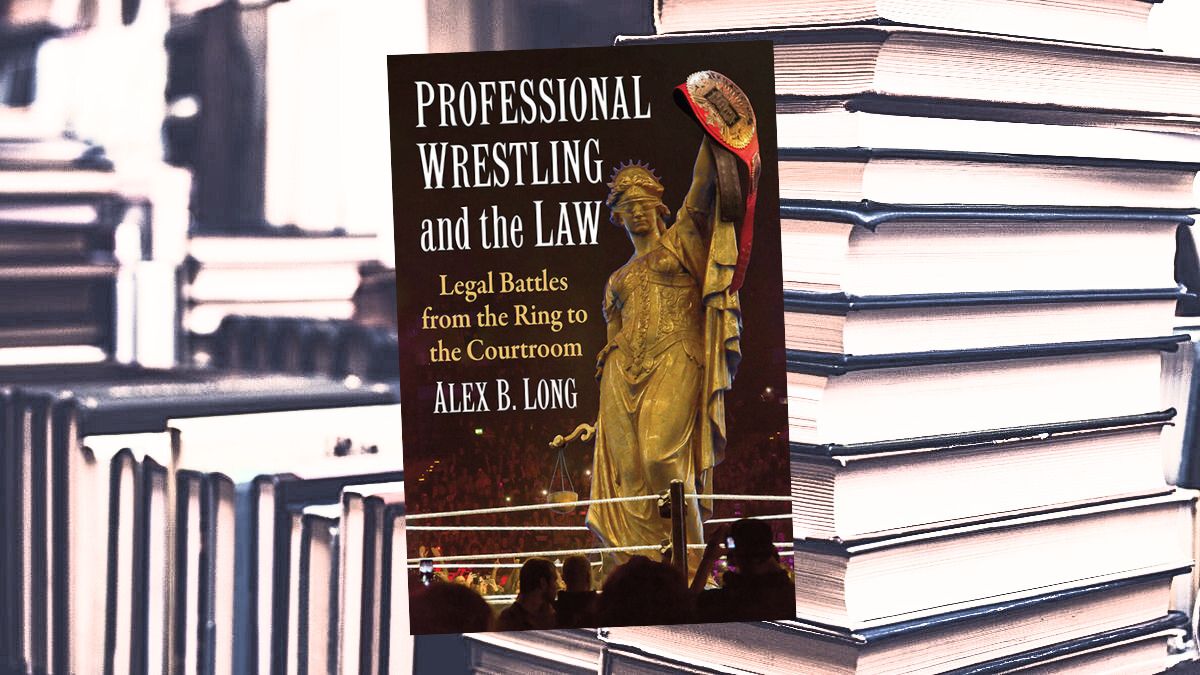

I was particularly excited to read Professional Wrestling and the Law: Legal Battles from the Ring to the Courtroom by Alex B. Long, a US law professor and lifelong pro wrestling fan.

As I frequently remind everyone within earshot, I am a lawyer myself. That said, I’m non-practicing and am more knowledgeable about Canada’s legal system than I am about the US — much less the peculiarities of all 50 states. I was excited to receive this assignment in the hopes that Professor Long might answer some longstanding questions I’ve had about how pro wrestling, its treatment of talent and business practices have evolved as they have.

Professor Long sets himself a difficult task. He defines his audience as including lawyers (anecdotally, there are an awful lot of us who are wrestling fans, even if many choose not to admit it) and laypeople. He seeks to describe complicated legal theories and history in a way that appeals to both. He tries to apply sociological economic and policy lenses to his work, addressing themes like the misogyny and racism which have (and let’s be honest, still do) pervade pro wrestling at all levels. It makes for a very interesting read, if not always a happy one.

Professional Wrestling and the Law, just released through McFarland, begins with a lengthy dissection of kayfabe — professional wrestling’s insistence that the world it presents including in-ring action and the personalities who fuel it are real. Historic court cases are presented where wrestlers and promoters went so far as to commit perjury to defend their livelihood, reinforcing legal doctrines that in some cases created no-win situations. Some US states had laws which prohibited ‘fixed’ fights that extended to wrestling, which meant that admitting pro wrestling was ‘just a show’ would constitute an admission of fraud. Up here in Canada some jurisdictions had similar laws, but savvy promoters got around them by classifying wrestling cards as ‘exhibitions’ of skill rather than full-on competitive sporting events.

The book starts in earnest with a discussion of two cases that would be familiar to anyone who came of age during the WWF-fueled wrestling boom of the 1980s: Reporter John Stossel’s lawsuit against then-WWF performer ‘Dr. D’ David Shultz (Schultz infamously slapped Stossel twice after the reporter dared ask the wrestler whether his craft was ‘fake’) and comedian Richard Belzer’s claim against WWF champion Hulk Hogan (Belzer had invited Hogan to appear on his talk show, then asked the Hulkster to demonstrate a wrestling hold on him; Hogan caught Belzer in a variation of a front facelock and Belzer fell to the ground, apparently unconscious, cracking his head open on the floor).

Professor Long asks his reader where kayfabe comes into play: is it the wrestlers who defend their careers against age-old accusations? Is it the claimants in the lawsuits — both ‘legitimate’ media personalities who scored large settlements that might have derailed the rock ’n’ wrestling phenomenon? Professor Long makes sure to note that Belzer used the proceeds from his settlement to buy a villa in France and that Stossel’s alleged pain and suffering resolved when his check from the defendants cleared. Is it the lawyers themselves, who tried to argue for a bigger piece of one settlement when they saw how lucrative it might be?

Throughout his book, Professor Long tries to place lawyers and the practice of law at least partly in the world of kayfabe. I understand it, but I would argue that most of us play a role at work that differs from who we are in our personal lives. Professor Long is quick to equate lawyers’ courtroom performances to anti-authority babyfaces or preening heels.

With respect, I think this is a bit of a stretch. One of my own professors often made the point that when most folks say that they ‘hate lawyers’ what they mean is that they hate opposing counsel. Their own lawyers are great. There is theatre in many legal proceedings. As Professor Long acknowledges, most cases settle out of court before trial, but Professor Long seems to suggest this is the result of lawyers fostering suspension of disbelief in the grind of the justice system. Most lawyers I know do the opposite. They zealously advocate for their clients’ positions where they are ethical and grounded in fact. In meetings with those clients, they will be clear about the prospects for success at trial and be the first to promote practical solutions in the face of emotional upheaval. Any lawyer I’ve met is attuned to the reality that even if a client wins, the expense of trial may turn that victory Pyrrhic. In my own brief foray into litigation, I quickly learned that taking a case to trial is generally worthwhile under two circumstances: if a client is truly committed to ‘bet the farm’ to recover a substantial award, or if that client feels so wronged that they need vindication from the justice system regardless of cost. I tend to think that settlement statistics show how grounded in reality the practice of law really is.

That said, Professor Long provides a series of cases that tested the bounds of kayfabe in great detail, going so far as to reprint excerpts from trials and copies of court filings. He pauses his accounts frequently to offer quick and useful summaries of legal concepts and does a great job parsing the turns of phrase that make up a lot of legal practice. It’s fun to see a rigorous analysis applied to the often-silly world of professional wrestling. It’s sobering to remember that for the parties involved, this silliness represents peoples’ livelihoods and in some cases was a direct cause of the worst days of their lives.

As someone who has made his career at the intersection of law and public policy and advocacy, I enjoyed Professional Wrestling and the Law. I read the book as a professional who is familiar with the legal and policy concepts involved. I particularly enjoyed sections devoted to antitrust law, labor and employment and fraud — areas where I think US law varies from Canadian law, and which have long given rise to systemic questions about how pro wrestling operates. Professor Long offers well-reasoned explanations grounded in applicable case law.

He doesn’t answer every question; I would have liked to see a more exhaustive review of the 2008 lawsuit brought by Scott “Raven” Levy et al. against WWE over their alleged misclassification of wrestlers as independent contractors vs. employees (I’ve written about that issue myself and still don’t fully understand why the case was dismissed well before trial. Professor Long simply states that the lawsuit “failed for a variety of reasons” — apart from the use of the term “independent contractor” on the face of the wrestlers’ contracts — which shouldn’t be dispositive, I would love to know more) but he offers the most cogent line of reasoning that I have come across and provides insights that go well beyond the usual wrestling talking heads.

Professor Long similarly grounds his takes on broader legal/policy issues like systemic misogyny and racism in the law. These sections most strongly reflect the kind of authoritative voice one would expect from a law professor, but the subject matter is serious and demands that approach. None of it is an ‘easy’ read, but the material isn’t easy. Professor Long expects that even if his readers lack a legal background they approach his book with a good bit of curiosity about how the system works. He rewards those readers by explaining these concepts and their application clearly and in an engaging manner. For what it’s worth, I would recommend this book as an introduction to many foundational legal concepts whether you’re a wrestling fan or not.

Reading Professional Wrestling and the Law I felt like a student in one of Professor Long’s law classes at the University of Tennessee College of Law in Knoxville. He writes like a law professor — an engaging professor, but a Prof nonetheless. As a result I admit that at points I felt lectured at rather than invited to engage with the material.

The book is thoroughly researched. A preponderance of footnotes means it is researched to a fault. Like most lawyers and academics I know (myself included) footnotes help cram a few extra points or arguments into a piece of writing that the writer just can’t bear to leave out. They do make for a more challenging read. As a student I pored over footnotes obsessively and they would often be the make-or-break points I’d need to regurgitate on a final exam. In most cases, for a book aimed at a more casual reader, they could be left out for readability’s sake without hurting the author’s point.

The footnotes feel a little at odds with Professor Long’s stated intent. He relies heavily on certain turns of phrase. Kayfabe is a key theme, often expressed by asking whether pro wrestling is “on the level”. It’s a fair approach but overused when it pops up repeatedly within the same paragraph. I get it: one of the first things we are taught in law school is the importance of specificity in language. A word is either ‘right’ or it’s dead wrong and could well cost you your case. Professor Long decided “on the level” was the ‘right’ way to capture the issue of legitimacy in pro wrestling and never looked back. From a legal writing perspective this is good practice. Non-lawyers might find it, and other expressions throughout the book repetitive. Although if you’re picking up a nearly 300-page book entitled Professional Wrestling and the Law written by a professor of the latter it would be unfair to expect him to use a different voice.

Perhaps my biggest takeaway from this book is the lack of attention that professional wrestling has received from the courts and the dismissive treatment it receives in that forum when a case does move forward. Despite clearly justiciable issues regarding corporate governance, labor and employment, discrimination and competition it seems like the law has often left pro wrestling to its promoters to figure out. Most of the cases cited in the book are dismissed before trial.

Professional Wrestling and the Law offers a successful and innovative marriage of two of my favorite subjects. Writing for SlamWrestling.net I have often tried to incorporate legal themes into my own work. It’s a challenge, and one that Professor Long meets admirably in longer form — which not only captures important case law but roots it in social and political issues from the beginning of kayfabe to the present day. I don’t agree with all of Professor Long’s takes, but any good lawyer knows that there is at least as much value in an opposing viewpoint well-argued.

As a book about wrasslin’ Professor Long provides an interesting and well-substantiated historical viewpoint, going so far as to reach out to some of the parties to the lawsuits he covers and test their recollections against the public record. I recommend it on that basis. I recommend it even more strongly as a book about the law whether you are a wrestling fan or not.

I have often said that all things are professional wrestling. Professor Long clearly shows that the law is no exception.