I write this column immediately following the April 24, 2024 edition of Dynamite. I was going to write about AEW’s post-All In creative funk and offer some helpful creative suggestions from the peanut gallery.

Then I saw this week’s show and thought, never mind.

Between AEW owner Tony Khan’s recent posts on social media, booking decisions including Chris Jericho, and the ending of this week’s Dynamite, I am convinced that AEW has decided on its path forward.

Welcome to what I will call the ‘Troll Era’ of AEW. May God have mercy on us all.

I’ve discussed wrestling’s use of social media before. Khan has been asked about his sometimes inflammatory social media presence. He prefers to see his tweets as fostering engagement with his audience and promoting his broadcasts. I may disagree, but then Khan would hardly be the first to think any reaction is a good reaction. In most cases involving pro wrestling, this is true. The problem arises when that reaction portends a rush to the exits by a fan base who feel betrayed. Beyond Khan’s comments, I worry that some mystifying booking featuring the likes of the Don Callis Family and new entrant Mercedes Monet may be starting to chip away at AEW’s good will… but those are stories for other days.

I will say that Jericho’s current run, which seems to steal Hook’s thunder along with his FTW championship is brilliant. Jericho has divided AEW’s audience into two camps: those who desperately wish he would go away and now chant “please retire” when he enters the ring, and those who are mortified by the apparent disrespect the chanting fans now show a genuine legend. I think it’s awesome, expert level trolling by Jericho, who’s getting exactly the reaction that he wants (as evidenced by a series of trademark applications). People often speak about Jericho’s promo ability, his move set and his ability to evolve his character — but this current version in which he condescendingly offers to sit younger wrestlers under his “learning tree” and hits them with a baseball bat leans into audience criticism that he now takes time away from less established talent, or uses them to bolster his own standing. It’s similar to Jericho’s ROH World championship run, wherein he increased the value of the title by setting himself in opposition to everything the promotion stood for; we couldn’t wait for him to be defeated back then, and we can’t wait for it now. It’s everything a heel should be.

The final segment of Dynamite was an even bigger troll. On a night where new AEW World Champion Swerve Strickland was relegated to a second-segment victory over the Don Callis Family’s Kyle Fletcher (without so much as a promo to put himself over as the new champion) and new IWGP champion Jon Moxley defended his title against Callis’ heater Powerhouse Hobbs, the main event slot was reserved for a reconciliation between “Pouty” Jack Perry and All Things AEW Tony Khan.

Jack Perry rips up his AEW contract

I confess to a degree of bias. I think Perry is a non-entity as a heel and following his confrontation with CM Punk back at All In, I think he’s ultimately every bit the destructive presence that Punk has been made out to be. I see the segment that unfolded as rewarding bad behavior, something pro wrestling has often done in the name of preserving the desired narrative. I also think AEW decided to troll its audience in earnest last week, when precious airtime was taken up replaying a mute copy of the video that showed the confrontation between Punk and Perry backstage at All In. It is apparent that Khan felt this would add interest to the Young Bucks’ tag team match against FTR, who were openly acknowledged as Punk’s friends, and for the purposes of AEW programming, his proxies. The whole thing seemed odd to me, as it profiled talent no longer employed by AEW, It generated a mild ratings spike, but numbers have been down since.

I’ll lift the proper recap of the segment from my SLAM colleague’s report: Dynamite: Jack Perry and Tony Khan meet face-to-face – Slam Wrestling

Jack Perry was out first and said that while he usually has a great time in Jacksonville, he has business to conduct tonight. Tony Khan comes to the ring. Perry said it’s been a long road as he continued to reflect on the first Double of Nothing five years ago, and says AEW has changed the world.

Perry said that he and Tony Khan haven’t always seen eye to eye, but all he’s ever wanted is what’s best for AEW. Jack Perry asks Tony Khan to shake his hand and reinstate them so they can change the world together. Khan shakes Perry’s hand, and the two hug.

Perry raises Tony Khan’s hand and then hits him with the mic. The Elite come down and they check on Khan. They slowly get Khan up and end up hitting him with a Meltzer Driver instead. The Elite posed over Khan. Members of the roster come out along with Shad Khan [Tony’s father and the ‘real’ owner of AEW] to check on Tony as AEW Dynamite goes off the air.

Quite the departure from AEW’s original mandate, especially given the younger Khan’s repeated statements that he does not want to play an onscreen role.

Since its inception in 2019 AEW has sought to differentiate itself from WWE by appealing to ‘serious’ wrestling fans.

It’s an interesting strategy, one which may or not be shifting as we speak.

WWE became the market leader and over the last 40 years has put most of its competitors out of business by focusing on (some would say pandering to) more casual fans.

WWE emphasizes storylines and product placement and merchandising opportunities ahead of in-ring action. It’s a strategy that has worked great for those of us who see pro wrestling as a male soap opera but has alienated fans who just want to watch great matches. AEW has done a great job of filling the quality gap in pro wrestling TV. AEW has made a point of signing capable in-ring performers and (albeit inconsistently for many of them) has given them the airtime to show what they can do. As a regular Dynamite viewer I can count on one to two good to excellent matches per show; depending on who gets time on the microphone there’s usually a fun promo or two wedged in the broadcast for good measure. At Vince McMahon’s nadir you could go months without any of that.

One can argue how WWE’s approach affects talent, and many wrestlers are vocal about their lack of creative fulfilment working for WWE. They do get paid (and talent who get over when the office allows it get paid handsomely) in a business that is notorious for shorting talent. For many years WWE was the only main American promotion with any visibility. WWE’s style, which emphasizes the same few safer spots in every match may be boring, but it could also be seen as safer than the daredevil moves required or permitted elsewhere. WWE wrestlers suffer their share of injuries, but in restricting moves with blind landings or that drop performers on their heads… and in providing a more regular work and travel schedule.

Those fans complain that with its vast and growing resources WWE has assembled an incredible roster of talent who are mostly relegated to short, repetitive matches that fail to showcase their skills, except for the rare Premium Live Event or televised match where these wrestlers have the chance to tell a longer form story. Even then those matches receive little follow up. Decorated wrestlers from other promotions fall down the card, leaving the general audience to wonder what’s so special about them in the first place.

The online wrestling commentariat has swiftly condemned Khan and his show-closing angle. In one respect, I can’t blame them. Greater minds than I have pointed out that in the vast majority of cases, a promotion that makes its owner the focal point of events is doomed to failure. This practice is bad enough when the owner is a wrestler himself, but it is understandable. Verne Gagne, Bill Watts, Fritz Von Erich and Jerry Lawler (to name a few) often placed themselves at the center of attention because they felt they alone could be trusted to advance the interests of their businesses. Crowning yourself (or proxies like your children) champion or enmeshing yourself in hot feuds means you can see storylines to completion without risk of your main eventer absconding or holding you up for a bigger pay day (at least not that you’d complain about it).

For his latest show-closing angle Khan has drawn unfavorable comparisons to other non-wrestlers who thought they could compete in the WWE-dominated arena.

Ric Flair and Ted Turner on a WCW/NWA program.

Perhaps the highest profile owner is Ted Turner. If you’ve been a fan for any length of time or watch television in general changes are you’re familiar with his work. Outside of wrestling he is perhaps best known for founding the news network CNN, for introducing the ‘superstation’ to the airwaves in the form of TBS and for his ownership of a number of media and sports properties (including the baseball’s Atlanta Braves). If none of this impresses you he also co-created the cartoon Captain Planet and the Planeteers. Turner got his start when he took over his father’s billboard business. He parlayed that into the purchase of an Atlanta UHF station well before ‘Weird Al’ Yankovic made UHF cool. That station would become the basis of a nationwide media empire, as the Federal Communications Commission allowed Turner to use a satellite to submit his station’s content to local cable companies across the US — the first superstation. Turner understood the importance of owning content for his outlet. In the late 1970s he bought the Braves and NBA’s Hawks to provide content for his TV station and, given the cross-country reach of his broadcasts, turning them into nationally recognized brands. In 1988 Turner bought the distressed Jim Crockett Promotions, which had worked itself into debt after its own ill-conceived purchase of Bill Watts’ UWF. Crockett’s television show had been a mainstay Turner’s network. Turner was never a terribly active owner, but during lulls in the business he resisted network executives’ pressure to cancel the show or wind up the brand. Turner held WCW as part of his portfolio until 1996, when he sold his broadcast empire to Time Warner, which was in turn merged with America Online to create AOL Time Warner. WCW’s greatest success — the Monday Night Wars — took place outside Turner’s time in charge. By 1999, as the pro wrestling boom was ending, WCW’s ratings and revenue eroded. Without an owner invested in its continuation (and a series of executives placed in charge of WCW who knew nothing about pro wrestling), WCW was shut down in 2001 and its bones were sold to WWE.

TNA was founded by wrestler Jeff Jarrett and his father, former wrestler Jerry. It was rescued from near bankruptcy by businesswoman Dixie Carter, who pumped millions of dollars into the company for over a decade in a bid to make it financially successful. In the latter days of her ownership she assumed an on-screen role, a female version of the ‘evil owner’ trope. Between her mediocre acting skills, generally derivative storylines and a series of misguided roster moves that alienated TNA’s fan base (which had been drawn to the brand for its use of younger, more acrobatic wrestlers) by presuming that the sun rose and set on Hulk Hogan and his cronies, Carter consistently lost money and left TNA in worse shape than she found it. TNA was ultimately sold to Canadian media company Anthem Sports and Entertainment, where it operates on a shoestring budget before minimal crowds, generating inexpensive content for Anthem’s networks. Diminished as it may be, TNA is still running and often puts on shows featuring some of the best in-ring action in the US and Canada.

Eddie Einhorn started the International/Independent Wrestling Association (IWA) in 1975. Einhorn was a successful broadcaster and sports executive. He held an ownership stake in MLB’s Chicago White Sox and served as their vice chairman (he had the 2005 World Series ring to prove it). Einhorn began his career in 1958, producing the nationally syndicated radio broadcast of the NCAA basketball championship. He stated his own network, the TVS Television Network, to broadcast college basketball games to regional networks well before the sport held national attention. He sold his interest in the network to become head of CBS Sports, and helped found the entity that would ultimately become the cable Sportschannel. Somehow he found the time to start up his own wrestling organization alongside established Northeastern promoter Pedro Martinez. The IWA followed Martinez’ earlier promotion, the National Wrestling Federation, which was based in Buffalo, New York, and had a significant following during its four-year run. Einhorn and Martinez anticipated the growth of pro wrestling well before WWE. They launched the IWA with the intention of promotion nationally but wound up concentrating their efforts on the Mid-Atlantic region. Einhorn presaged Vince McMahon’s expansion tactics. He offered talent more money and benefits to come work for him, and succeeded in drawing talent like Ernie Ladd, Mil Mascaras, Mighty Igor, Bulldog Brower, Ox Baker, the Wild Samoans and the Mongols. Einhorn sought to compete directly against the then WWWF, running house shows in McMahon’s territory and at one point knocking him off television in his New York home base (the WWWF had to find a temporary home on a Spanish-language station to keep its presence in its biggest market). Einhorn’s tenure with the IWA did not last long. He left before the end of 1975, citing business conflicts and financial losses. The promotion continued on a smaller scale for three years, mainly operating in Virginia and North Carolina, run by Johnny Powers. It closed in 1978 after attempting to sue Jim Crockett Promotions for anti-trust violations, alleging that JCP prevented the IWA from promoting its shows in the regions larger venues. The lawsuit failed and the promotion went out of business, although the promotion’s reach extended to airings of its TV show in Nigeria and Singapore in the late 1970s.

Outside traditional business, music producer Rick Rubin was a chief financial backer of Jim Cornette’s Smokey Mountain Wrestling at its outset n 1992. While popular among hardcore fans, Smokey Mountain never quite caught on; it was deliberately pitched to a local crowd, which made it difficult for the promotion to grow or secure a television deal of any scope (ironically, the issue of regionalism was one of the first things that Eric Bischoff addressed when he took WCW’s reins, transforming WCW from an old school “Southern ‘Rasslin’” promotion to a polished, nationally-minded concern made WCW competitive in a mass market). Smokey Mountain folded in early 1996 after Rubin pulled his funding.

Today, former Smashing Pumpkins front man Billy Corgan continues to try to make the National Wrestling Alliance great again. He took over the organization in 2017 after it had been reduced to a few shreds of intellectual property. One of Corgan’s first moves was to transform the NWA from a sanctioning body with nothing to sanction, to a standalone promotion which attempts to combine classic wrestling tropes with modern performers and matches. Viewed charitably, the NWA looks like it’s run on a narrower shoestring than TNA; it has also relied more heavily on former WWE acts who have filtered through AEW, TNA, ROH and larger independents before settling in Corgan’s promotion for however long — but it has also helped elevate a few careers on their way back to the big time. I would not buy a ticket for Trevor Murdoch or Tyrus as world champions, but I could have been persuaded to go see Matt Cardona, Eli ‘LA Knight’ Drake, Nick Aldis or Cody Rhodes on their ways back up the ladder. The NWA provides a showcase for talent who have been slept on by other promotions, including current champion EC3. In late 2023 the NWA announced it would re-establish its system of territories; we’ll see where that goes.

The above examples feature would-be promoters and investors who came to pro wrestling after distinguished (or infamous) careers in other fields. Wrestling lore is littered with stories of individuals who felt their best shot at fame and fortune.

As stated in the Leonard Bernstein musical Wonderful Town: “A million kids just like you come to town every day with stars in their eyes. They’re going to conquer the city, they’re going to grab off the Pulitzer Prize, but it’s a terrible pity, because they’re in for a bitter surprise. And their stories all follow one line…”

New York born Herb Abrams’ UWF lasted on paper from 1990 to 1994. Like Khan, Abrams was a lifelong pro wrestling fan. In 1976 he sought entry into the world of pro wrestling via veteran journalist Bill Apter. Abrams asked Apter to recruit wrestlers to appear at Abrams’ father’s womenswear store, offering free dresses for the wrestlers’ wives in exchange. Abrams moved to Los Angeles and after starting a series of non-wrestling businesses, founded the UWF in 1990. Unlike Carter or Turner, Abrams financed his new promotion with $1 million received from SportsChannel America to produce a weekly television show. Abrams believed his promotion would succeed despite his lack of a wrestling background, figuring he could get by on “Hollywood glitz.” He also turned out something of a grifter, running his promotion without paying venue owners or talent. Perhaps because getting paid is a prerequisite for most wrestlers, UWF storylines were often ragged and ended without clear conclusions. The matches themselves rarely went to a finish which was frustrating for fans. Abrams did practice an early form of trolling, naming one of his enhancement talent ‘Davey Meltzer’ after the established pro wrestling journalist. The UWF TV show lasted a year. The promotion hung on for another three years in name, holding occasional live shows until 1994. By that point Abrams cashed in his chips, betting on a television special that aired live from the MGM Grand Arena in Las Vegas. Only 300 people showed up for the event, held at a venue that could accommodate 17,000. Struggling with substance abuse, Abrams died less than two years later.

Gordon Scozzari in the ring with the AWF title belt at an AWF show. Photo by Mike Lano, WReaLano@aol.com

One sad example Gordon Scozzari, who, at age 21, founded the American Wrestling Federation in 1991 with money he either made off of a shrewd investment or inherited on his parents’ deaths. Scozzari hoped to create a third national promotion and ran a series of TV tapings that leveraged established WWF and NWA stars and international acts from All-Japan Pro Wrestling and Puerto Rico’s World Wrestling Council (WWC). Scozzari’s efforts were plagued by production challenges, including prominent wrestlers no-showing cards after getting paid up front, and empty houses that followed questionable business decisions like running shows in a tourist town during the winter. Scozzari had hoped to syndicate the shows he created but wound up salvaging them to be aired on Mario Savoldi’s International World Class Championship Wrestling program. Scozzari made other attempts to get in the business, notably in a similarly ill-fated venture in Puerto Rico. Having suffered from kidney disease his whole life, he passed away in 2011.

Ironically Scozzari believed that the UWF’s Herb Abrams set out to sabotage his promotion, which operated close by and shared wrestlers. Scozzari claimed that Abrams bribed wrestlers to ‘no show’ Scozzari’s TV tapings. Wrestlers including Dr. Death Steve Williams, Dan Spivey, Paul Orndorff, Junkyard Dog and Sunny Beach (Scozzari’s head booker) have all been implicated.

Wrestling fans are never happy. Despite their displeasure with the carny nature of ‘inside’ promoters like the McMahons, they attack these interested ‘outsiders’ as ‘money marks’ — naïve non-wrestlers who are conned out of significant sums of money by grifting grapplers, with little to show for it. In some cases, this may be true. Scozzari’s story is particularly tragic. But he made a number of business decisions that would have been flawed regardless, against advice from friends who legitimately had his interests at heart.

Khan catches a lot of flack for being a fan first. I am not sure that is fair. Ted Turner’s support of WCW carried the promotion until its sale to Time Warner led to its demise. Dixie Carter became a fan and kept TNA going even when her balance sheet might have dictated otherwise. Anthem put the promotion in Scott D’Amore’s hands until they fired him earlier this year in a bid to contain costs, even as D’Amore advocated for greater investment in order to grow the brand. I would like to be more optimistic about TNA’s fate given the promotion’s status as a content provider owned by a broadcasting company, but wrestling companies without owners to champion them don’t seem to last long. It’s worth noting that as expensive as WCW may have been, it also had the advantage of falling under the same umbrella as Turner’s TBS and TNT superstations — in fact, Turner bought the former Jim Crockett Promotions partly out of loyalty to a company that drew eyes to his networks in their early days. Ring of Honor filled the same role for the Sinclair Broadcast Group until, facing mounting debts across their business, Sinclair put ROH on hiatus in 2021 and ultimately sold the company to Khan (Khan’s failure to do more with ROH since them deserves its own column). Whether you like the McMahons or not, until recent years WWE was never just an asset — it was the family’s livelihood. Even Vince McMahon was a fan before he became the boss. He has told the story about being drawn into the world of wrestling by Dr. Jerry Graham, going so far as to buy a red suit and dye his hair platinum blonde to match his hero. Wrestling does better under the stewardship of its fans than as a line on a balance sheet. It needs to be more than cheap TV to survive.

So far as audience trolling goes, AEW has drawn criticism since its inception by appointing active wrestlers like the Young Bucks, Kenny Omega and Cody Rhodes to senior executive positions when the company started. At the time, fans asked how talent could be trusted to lead in a readily apparent conflict of interest. I never quite got the fuss: as noted above, wrestlers have held a piece of the office since the territory days. Bringing them into ownership was and is still a way of fostering loyalty and continuity in a transient business. I never saw a functional difference between Omega, the Bucks and Cody versus the likes of Whipper Billy Watson, the Sheik, Gorilla Monsoon, Eddie Graham, Stu Hart, Nick Gulas, Bob Armstrong, Dick the Bruiser, Verne Garne, Bill Watts, Dusty Rhodes, or the Jarretts, Von Erichs, Funks, Maivias, Fullers, Mulligan/Windhams, Vachons, Rougeaus, Dupres, and I know I’m missing a bunch.

All of these promotions saw their share of success and failure based on the talent available and the storylines employed to draw audiences. At points all of these promotions faced the same criticisms as AEW’s executive wrestlers — which is odd, since I would argue that Cody Rhodes, for example, deliberately undervalued his in-ring presence. By the time AEW started, Cody had the benefit of an extensive WWE run, plus championship credibility as a former ROH and NWA titlist. He could have booked himself as a world-beating AEW champion but deliberately opted not to. Instead he had several secondary title runs and served as a gatekeeping first feud for debuting heel talent like the late Brodie Lee, Andrade or Malakai Black. Omega had an extensive run as an early AEW champion but he joined off of an incredibly hot run in NJPW — and AEW was created out of a desire to spotlight wrestlers like him. Omega, who has had a few extended layoffs due to injury and illness, has opened up about his limited involvement in an executive capacity. I believe him and hope he recovers to continue doing what he does best: putting on main event matches.

As long as it exists, AEW will face criticism between crowning champions who lack the first-rate exposure that comes with the WWE championship, or else picking up ex-WWE stars and slotting them into title runs which feels derivative and makes AEW out to be second rate. Even current champion Swerve Strickland, who was released by WWE before joining AEW and setting the company on fire with his next-level matches, has been derided as a castoff. Current storyline aside, I think AEW’s brain trust has done a good job for the most part.

That’s not to say that I agree with AEW’s apparent shift to trolling its fans. On one hand, the EVP business demands a course correction. It feels too ‘inside baseball’ to sustain interest and as good as the Bucks, Okada and Perry may be, they are too small, too bland and do not feel like a main event threat. I get that the Elite is supposed to be a spiritual successor to the NJPW Bullet Club stable, but without heaters like the Guerrillas of Destiny, Bad Luck Fale or the Good Brothers they’re missing the all important heel intimidation factor. Their most interesting singles competitors are ‘Hangman’ Adam Page and Omega, both former AEW champions, and both sorely missed from an in-ring perspective — which raises a legitimate systemic issue in AEW’s privileging in-ring talent above all else.

A top level heel stable needs to be able to talk the audience into the building, so we can cheer for them to get their comeuppance. AEW has a few gifted vocalists, but they’re nowhere near this angle. AEW has struggled as much with Okada as it has with other non-native English speaking wrestlers (and some native English speakers with accents that are challenging for North American ears, like Ospreay). The solutions they have found are turnoffs. Established managers like Don Callis or Stokely Hathaway get limited platforms while cyphers like Jose the Assistant (since released) or Alex Abrahantes are trusted to speak for talent, which eventually cools them off. On Dynamite, Japanese wrestler Katsuyori Shibata resorted to a female-voiced translation app on his smartphone during an interview with Renee Young. Somehow the app had Shibata’s lines set up so he did not need to say or type anything into the phone. It’s not quite WCW overdubbing La Parka in ‘jive talk’ or WWE gifting Sho Funaki a second career with his ‘Indeed’ promos, but it is not much better. Somewhere, Vince Russo weeps and the audience trolling ramps up a notch. The Bucks are fantastic flyers but I could not give an example of a compelling promo. Jack Perry has turned his post-All In suspension into a push that I suspect outstrips his abilities, but we’ll see. He was a decent white meat babyface as Jungle Boy. So far he is absolutely flat as a heel.

For Khan’s first physical involvement in an angle, the Daley’s Place crowd (which was apparently heavily papered) was subdued. Regardless of where this storyline is headed I suspect it will be difficult to effectively cast Khan as a sympathetic figure. His social media presence and penchant for hugging new signees suggests that he sees himself as a proxy for the audience laboring to build a product they will love. Increasingly fans see him as another disconnected billionaire treating talent like very expensive action figures. Taking him out from behind the curtain feels like a no-win proposition. For fans who love to complain (and we are legion) Khan is seen as the personification of everything wrong with AEW. He’s looking for love from a fan base that finds fault with everything. If Khan is meant to eventually turn heel, well, we’ve seen that show before and reheating 30-year-old ideas will only serve to alienate an audience that sees AEW as more late-stage WCW than Attitude Era WWE… either of these comparisons is detrimental. Wrestling needs to be at least somewhat forward looking in order to build anticipation to the next event. I’m all for recycling ideas that work, but when the competition is going to great pains to dissociate itself from the problematic parts of its history, Khan’s efforts feel strange.

I’m sympathetic to a point. Khan has admitted that he takes the lead in writing most of his shows. It’s one of the many roles he plays as President, Chief Executive Officer, General Manager and Executive Producer of AEW. This in addition to various roles in other aspects of the family business. Khan has claimed to work 90-hour weeks. He is abetted in the creative department by the likes of Bryan Danielson, Sonjay Dutt, Jerry Lynn, Jimmy Jacobs and Will Washington and recently hired former WWE writer Jennifer Pepperman, who had a particularly strong working relationship with Mone. Khan has surrounded himself with creative wrestling minds who have proven track records in other companies. He has also made clear that the buck stops with him, and, as with WWE in recent years that could be part of the challenge.

Khan has also admitted that he can’t do this forever. In a recent interview he noted that while he feels capable of running AEW at 41 years of age, he anticipates that he will have to turn over the company’s direction at some point. I would hope that whenever that day comes AEW is a thriving promotion and the decision to be made is one of succession rather than the continuation of AEW as a whole. However one may feel about the promotion, pro wrestling is better with AEW. It offers more places for talent to work and a better chance at fair compensation. It gives wrestlers a place to go to refresh themselves and if need be, return to WWE in a stronger position than when they left. Just ask Cody Rhodes.

Speaking of AEW taking advantage of talent who have left WWE, if I am correct and this week’s Dynamite signals a turn to trolling AEW’s haters, Khan urgently needs to come up with an answer to his problem with the Elite. He needs an in-ring leader to counter the Bucks’ smarminess and Perry’s blandness. A better-than-physical matchup against Okada who has his own championship pedigree and a ready supply of available backup.

Seth Rollins (left) and Jinder Mahal talking trash to one another. Credit WWE

On April 19 that man, along with his burly associates received his walking papers from WWE. If Tony Khan really wants to troll his audience, he will sign former WWE Champion Jinder Mahal along with his charges Indus Sher as soon as their non-compete clause runs out. I’m on record as a Jinder Mahal fan; I wrote a lengthy plea for WWE to push him following his confrontation with a returning Dwayne ‘The Rock’ Johnson back in January. I didn’t mean for WWE to push Mahal out the door while giving The Rock the heel run that Mahal could have used (OK, I did not expect Jinder to main event WrestleMania — at least this year). But the WWE’s failure to take advantage of Mahal-Mania should be AEW’s opportunity. Recall Khan’s reaction when Mahal received a title shot against Seth Rollins after his promo with The Rock. Khan was incredulous that Mahal would get a title opportunity despite a long losing streak. He then used the tweet to promote his main event of Hook vs. then-AEW world champion Samoa Joe, to which Mahal responded “Who’s Hook?”

Pro wrestling makes for strange bedfellows, and it’s time Khan and Mahal got cozy. Mahal is making media rounds since he was released. He thanked Khan for drumming up interest in his match against Rollins (which was very good, if too short, and teased the possibility of a Mahal win on a few occasions). The same audience that went flat for the Elite attack is now calling for AEW to hire Mahal and company as the company’s saviors. Even Eric Bischoff agrees.

I think it’s a brilliant idea, especially with Mahal and Indus Sher playing against stereotype as babyfaces. Even better if they team them up with Satnam Singh, who is largely just background for Jay Lethal and Jeff Jarrett. Better still, throw Sonjay Dutt in the mix (or the Bollywood Boyz) and you have a logical stable with all the tools to run over the spot-heavy charisma-light AEW roster, while premising their run on a social media beef with the boss.

I can’t think of a better way to troll the trolls.

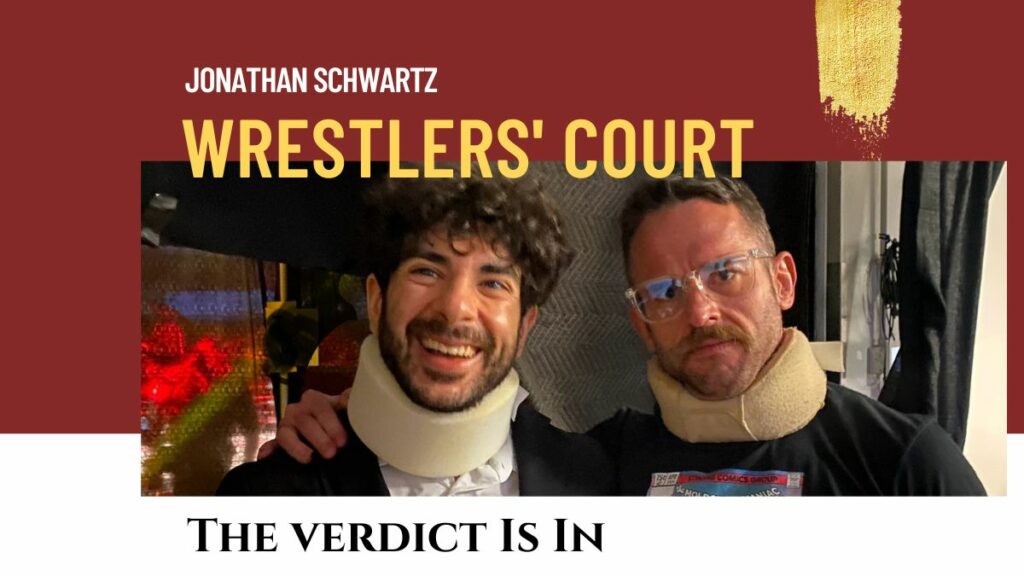

TOP PHOTO: Tony Khan and Roderick Strong with matching neck braces in late April 2024. X photo

RELATED LINK