It was the eve of October 31, 1934, at Arena Nacional in Mexico City. Tiger Hernandez had just achieved a win over Eugenio Munoz. Before exiting the ring, Munoz had an announcement to make to the fans: henceforth, Eugenio Munoz will be known as Jimmy El Pulpo (Jimmy the Octopus). What better time than the approaching Dia de Los Muertos to put an identity to rest? And why wait for a new season to spring to life with a new identity?

Born in Aguascalientes, Mexico, on November 15, 1908, El Pulpo was a fitting name for the six-foot-one muscular — albeit lanky — gentleman who left home in his early teen years in search of work.

“He did run away from home, and that was to start a career,” says daughter Katherine Rutherford. “They lived a small, meager existence, and he had to make money. He was an extra mouth to feed.”

In search of making a living, Munoz tried several different lines of work, including a stint in the military. A keen fan of athletics, Munoz participated in boxing, baseball, and the sport that would become his career for a good 16 years, professional wrestling.

If he had his druthers, Eugenio Munoz would have become a professional boxer. “(Boxing) became a talent he tried to excel in,” says Katherine. “He was good, but he was a better wrestler than he was a boxer.” Perhaps Jimmy also recognized, as did some pugilists of the era, like Whiskers Savage and Bobby Pico, that wrestling was a more reliable way to make a living than boxing.

This is not to say The Octopus Man disliked wrestling. “He was a man of all seasons, he could shoot, he loved hunting, he loved sports, he loved being physically fit,” says his other daughter, Lorraine.

He began his career wrestling for promoter Salvador Lutteroth’s newly formed Empresa Mexicana de Lucha Libre (which still thrives today under the banner of Consejo Mundial de Lucha Libre, the world’s oldest existing wrestling promotion) along with fellow EMLL pioneers Charro Aguayo, Ciclon Mackey, Dientes Hernandez, Eddie Palau, and Walter “Sneeze” Achiu.

A posed photo of Jimmy El Pulpo autographed to fellow wrestler Roland “Speedy” Warren, from the Estate of Roland Warren

Although he enjoyed great success in Mexico, his dream was to live in the United States. He hit the American scene in 1937, gaining main event status in Texas, Arizona, and Northern California.

It was the Southern California territory where the 6-foot-1, 215-pound Pulpo received his strongest main event run, though, under promoter Jack Daro, who had recently been given the reigns as promoter from his older brother, Lou.

Julio Mueller, from Mexico’s polo team, is seen in a photo with El Pulpo in 1937. The polo team was attending the matches at Los Angeles’ Olympic Auditorium to cheer on El Pulpo.

The idea was to create a fresh Latino star for the local Hispanic wrestling fans to replace superstar Vincent Lopez. Born Daniel Lopez in Meridian, Ohio, he was a talented wrestler who was box-office gold in Southern California throughout the 1930s, and he held a version of the world heavyweight championship.

Daro immediately pushed Jimmy El Pulpo into the main event slot in Los Angeles. “Jack Daro attempted to see if lightning could strike twice by giving a promotional push to a Latino wrestler,” wrote wrestling historian Rock Rims in his 2020 book Legends and Icons, which covers the history of professional wrestling in Southern California. The promotion put out a mountain of publicity on The Octopus Man, including features and a photo op in the Los Angeles Times with former world champion Strangler Lewis, presenting a storyline in which Lewis was interested in managing the emerging mat star.

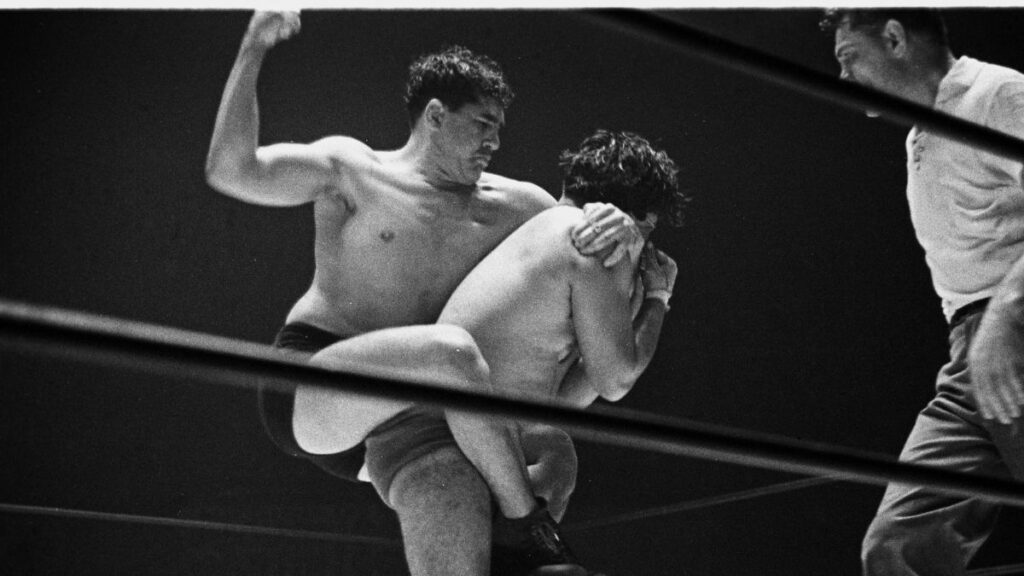

Jimmy’s appeal was his technical wrestling, which one old-school journalist saw as reminiscent of Joe Stecher, while another veteran writer saw his legwork as gimmickry. He took down wrestlers utilizing his legs, locking them in exotic grips, often “putting the hooks” into his opponents, the move we see today as the road to a submission in MMA bouts.

The most popular hold in Pulpo’s arsenal was his Octopus Hold, which he used both as a submission move as well as a pinfall technique. Judging on descriptions of his matches in the newspapers, his submission version of this hold might be recognizable as the Octopus Hold made famous years later by Antonio Inoki, where the descriptions of Pulpo’s pinning technique sounds akin to the poetic rolling pinfall that Terry Funk and Manami Toyota used in their heydays.

Jimmy El Pulpo with the Octopus Hold on an unknown opponent in 1937. Photo courtesy Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive, UCLA Library Special Collections.

El Pulpo’s push was successful. By November 24, he was already in the main event versus former world title holder Gus Sonnenberg at the famed Olympic Auditorium in Los Angeles. The press portrayed Sonnenberg as vying for a shot at the championship he once held, and El Pulpo was the wrestler he needed to beat to gain a match with then current champ Jim Londos. Sonnenberg, who just ten years earlier was one of pro wrestling’s most innovative and dynamic wrestling superstars, was now on the rapid downswing of his career. A combination of heart issues, heavy drinking and personal complications left Sonnenberg looking quite weathered compared to the firecracker of a performer he once was. That said, Gus was still very popular with the fans and could still perform well enough to get the job done.

The match drew a sellout of 10,000, which included actor Peter Lorre, who marveled over the night’s matches: “Not only is it amusing, but it’s a real education for an actor, a post-graduate course.”

Sonnenberg took the first fall after polishing off Pulpo with a series of elbow smashes. The second fall saw Jimmy coming back on Gus with a barrage of dropkicks. Gus rebounded, trying to nail Jimmy with his famous flying tackle, only to have Pulpo dodge each one of them, with the final attempt seeing the former champ sailing out of the ring to lose on a count out.

But fall three saw Pulpo pin Sonnenberg with the Octopus Hold in seven minutes and 27 seconds. The clean win showed that Daro had big plans for The Octopus Man, placing him alongside Sandor Szabo as a contender for Jim Londos’ championship.

The next few months saw Jimmy grapple with the stars of the southland including Chief Little Wolf, Bill Longson, Abe Goldberg, Pat Fraley, Sandor Szabo, Del Kunkel, and the sibling trio of Tom, Chris and George Zaharias. With the exception of putting over George Zaharias and trading a win apiece with Sandor Szabo, El Pulpo was planted securely in the winner’s column.

The year 1938 looked to be promising for Jimmy’s career, but that turned out to be a very rough patch for him, suffering injuries that tempered his main event status. He was slated to meet Jim Londos for the world championship at The Olympic Auditorium on March 2, 1938. Unfortunately, Mother Nature had other plans.

A powerful storm hit Los Angeles, Orange, and Riverside counties between February 27 and March 1, causing the worst flood the region had ever experienced. The result was horrific. Over 5,000 homes and businesses were destroyed, multiple roads and bridges were washed away, and 115 lives were lost to the disaster.

The city of Los Angeles was pretty much shut down, which saw the Jimmy El Pulpo versus Jim Londos title match postponed.

The card that didn’t happen at the Los Angeles Olympic Auditorium on March 2, 1938.

Even if the weather had mellowed enough for the match to take place, El Pulpo would have been unable to perform. The March 2 edition of the Ventura County Star reported that Chris Zaharias had broken El Pulpo’s wrist during their match the previous evening. The truth is that Jimmy did indeed break his wrist, but he broke it the evening before his match with Zaharias while taking part in rescue efforts after the storm caused a mudslide that destroyed Roosevelt Highway in Santa Monica Canyon.

The city of Ventura was spared the worst of the storm, so his match with Zaharias was still on. Instead of cancelling their match, Zaharias and Jimmy turned Pulpo’s injury into an angle. The two threw together a quick five-minute, two-out-of-three falls affair. Jimmy hid his injury from the fans, scoring the opening fall from Zaharias in just over a minute. Zaharias gained the second fall in just 38 seconds. The third fall consisted of Zaharias being disqualified for hurling El Pulpo out of the ring. Jimmy clutched his wrist in pain, the ringside doctor confirmed that it was indeed broken, and Jimmy swore revenge against his foe.

Jimmy returned to the wrestling scene by May, but another break to the same wrist led to another tough break in his career, courtesy of a new entry in the wrestling business, Dr. Patrick O’ Callaghan.

Dr. Pat O’Callaghan vs El Pulpo at the Los Angeles Olympic Auditorium on June 1, 1938.

Dr Patrick O’Callaghan of Ireland was the newest pet project of promoter Paul Bowser, who had considerable sway when it came to grooming future world champions. O’Callaghan did his country proud when he won gold medals in the hammer throw event in both the 1928 and 1932 Olympics. He was also an accomplished amateur wrestler, but too inexperienced of a professional wrestler to work on a main event level. He was also very arrogant, hesitating to sell moves by his opponents.

His second match during a nationwide tour of the U.S. was versus El Pulpo at The Olympic Auditorium on June 1. El Pulpo and O’Callaghan went for nearly eight minutes without neither man leaving his feet, nor gaining any advantage. Dr. O’Callaghan then applied a “track and field” finishing move designed for him, dubbed the Hammer Throw. The move in this match was described as O’Callaghan securing something akin to a hammerlock on El Pulpo, swinging him in circles, and then hurling him out of the ring.

Pulpo’s wrist was rebroken due to the Hammer Throw. Either unaware of or insensitive to Pulpo’s injury, O’Callaghan awkwardly reapplied the hold and pinned Jimmy. By news accounts and a press photo, Dr. Patrick seemed none too concerned over his opponent’s injury.

O’Callaghan’s undefeated win streak continued until August 17, when he faced a contender who had no plans to work with his opponent. Enter Dr. Patrick’s opponent for the evening, George “KO” Koverly, wrestler and bad-ass extraordinaire. Although their match was not the main event of the evening, KO promised that his match with O’Callaghan would be the match that folks would remember best. A frequent opponent of El Pulpo and the other local boys, perhaps KO was fed up with the treatment Dr. Patrick had bestowed upon his comrades.

Koverly kept his promise in a match that the L.A. Times described as “a gory affair.” Taping his fists and soaking them in cold water before the match, Koverly spent the entire bout boxing Dr. O’Callaghan’s face into oblivion. No holds were displayed, all the action was courtesy of Koverly’s fists. One split nose, two ripped lips, and twenty minutes later, the referee jumped in and awkwardly called the match a no-contest once Koverly punched a nasty gash over O’Callaghan’s brow. “When O’Callaghan got out of the ring, he looked like a page full of war horrors,” recalled San Francisco promoter Joe Malcewicz.

The Hammer Throw King was scheduled to wrestle accomplished shooter in Canada shortly thereafter in Fred Grubmeier. Grubmeier, who Lou Thesz once described as a skinny unassuming man with a face like Ichabod Crane, was actually a wolf in sheep’s clothing, a true shooter in his day. O’Callaghan wisely no-showed the match and caught a ship back to Ireland, citing a family illness (Perhaps the illness was his own traumatophobia, the fear of battle?). Thus ended the clumsy wrestling career of Dr. Patrick O’Callaghan.

El Pulpo tugs at Vincent López at the Olympic Auditorium in Los Angeles, 1937. Photo courtesy Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive, UCLA Library Special Collections.

Pulpo returned to the ring in late August, but the momentum of his main event status lulled. He had with a rematch with Sonnenberg on September 14 that drew 5,500, barely half the number of fans they drew the previous year. Pulpo was again the winner, but both his main event status and the strength of the Daro promotion began to wane.

As 1939 rolled in, Pulpo was now more of a supporting player in Los Angeles, though he still served as a frequent main eventer in smaller towns. He did finally get two title matches with Jim Londos over the next year, one in San Bernardino and the other in Stockton, each match seeing the champ win in straight falls.

Jimmy’s injuries and the end of his feature status were no doubt a disappointment, but not heartbreaking. While his wrestling schedule was still quite busy, he was already mapping out his post-wrestling career. He was firmly settled in the state of California and was already looking at a line of work with more security than pro wrestling. He scored a good paying job at one of the local dams, and he stepped away from wrestling for the entirety of 1942 to serve in the Merchant Marines, working in a munitions plant.

Jimmy El Pulpo in 1946.

His schedule throughout the 1940s tended to favor smaller arenas, often close to his home in Fresno. Researching his wrestling schedule in 1946 shows that he took what was likely a working vacation across the country. He would spend several weeks in one territory with main event hype, winning his initial matches before doing the honors for the local hero or heel, and then hitting the road.

In an April 1946 appearance in Asbury Park, New Jersey, he was the villain the eyes of columnist Sam Siciliano: “El Pulpo draws the crowd because he is so ugly. He even brags about the title of being the most ferocious looking man in the ring today. And he swears that Boris Karloff almost fainted when he took a good look at him when they came face to face in Hollywood recently.”

Jimmy El Pulpo versus Chief Little Wolf, circa 1937. Author’s collection

El Pulpo married in 1949, which is the year he had his final match as a professional wrestler. Eugenio Munoz had by now legally changed his name to James Hernandez Munoz, keeping the “Jimmy” in his name, but leaving any cephalopod references behind. He and his wife had three children, James Jr., Katherine and Lorraine.

Jimmy’s children knew very little about their father’s wrestling career. Both he and his wife believed in looking forward, leaving the past in the past. “We never asked, and he never told us,” says Lorraine. “That’s how we were raised. We’ll ask (our mother) about her life, and she won’t let on. And it was hard for me to ask what we wanted to know. I was born in 1952, my brother was born in 1950, and my sister was born in 1953.”

This is not to say that we are left without valuable information on James Munoz. The artist previously known as Jimmy El Pulpo was just getting warmed up. “Everything he did was to make money to travel,” says Katherine. “He wanted to get it out of his system before he permanently settled down in life. After that, everything he did was more for his family than it was for himself. Making mom happy was his top priority.”

Jimmy worked at the dams non-stop so that he could move his family to the prospering suburb of Redding in Shasta County. Retiring from the wrestling business did not slow him down, quite the opposite. He became a perpetual motion machine of sorts via an array of interests, many of which he took part in with his children.

“He was always active,” says Katherine. “When one activity stopped, there was always another.” Over the years, Jimmy loved to fish, raise Dermot Shorthair dogs, horseback riding, and he donated time to a boxing program at Atascadero Prison. He was also an avid hunter. “He would (design) the stocks to his guns, his hunting rifles, he engraved all the wood on that. He did the leatherwork on all his gun cases, beautifully done,” adds Katherine.

On top of that, he was the sole chef of the family. “Try everything in life,” he told his children. “And he would try it,” says Lorraine, “whether he liked it or not!”

Jimmy and his wife divorced in 1970, and he relocated to the coastal city of San Luis Obispo. “Making Mom happy was his top priority,” repeats Katherine. “It didn’t seem to happen that way, because they ended up divorcing. You can try your hardest to make someone happy, but if that person’s just not happy, it’s not going to work. Money doesn’t buy happiness.”

Katherine says that her father found a new home in the coastal city of San Luis Obispo, and threw himself into the activities he loved, and he added scuba diving into his already impressive repertoire in his 70s.

As Pulpo grew older, he reconnected with family in Aguascalientes, and spent time with his grandchildren. “I had to watch him with my son,” chuckles Katherine, “because he had sort of a free hand, letting my son do an awful lot. He was bringing in the guns, the knives, the vehicles: he adapted his car for my son, and he put these blocks on the clutch and the brakes and the gas pedal, so he could drive the car on the beach!”

Pulpo kept busy and stayed in excellent physical shape until the end. His only frustrations were being unable to master the art of stained glass (he excelled at all his other hobbies) and Father Time, “growing old and saggy,” says Katherine.

James Hernandez Munoz/ Eugenio Munoz / Jimmy El Pulpo died on July 26, 1991, at the age of 82. The Octopus Man was really one groovy cat that lived more than his assigned nine lives.

TOP PHOTO: Jimmy El Pulpo with the Octopus Hold on an unknown opponent in 1937. Photo courtesy Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive, UCLA Library Special Collections.