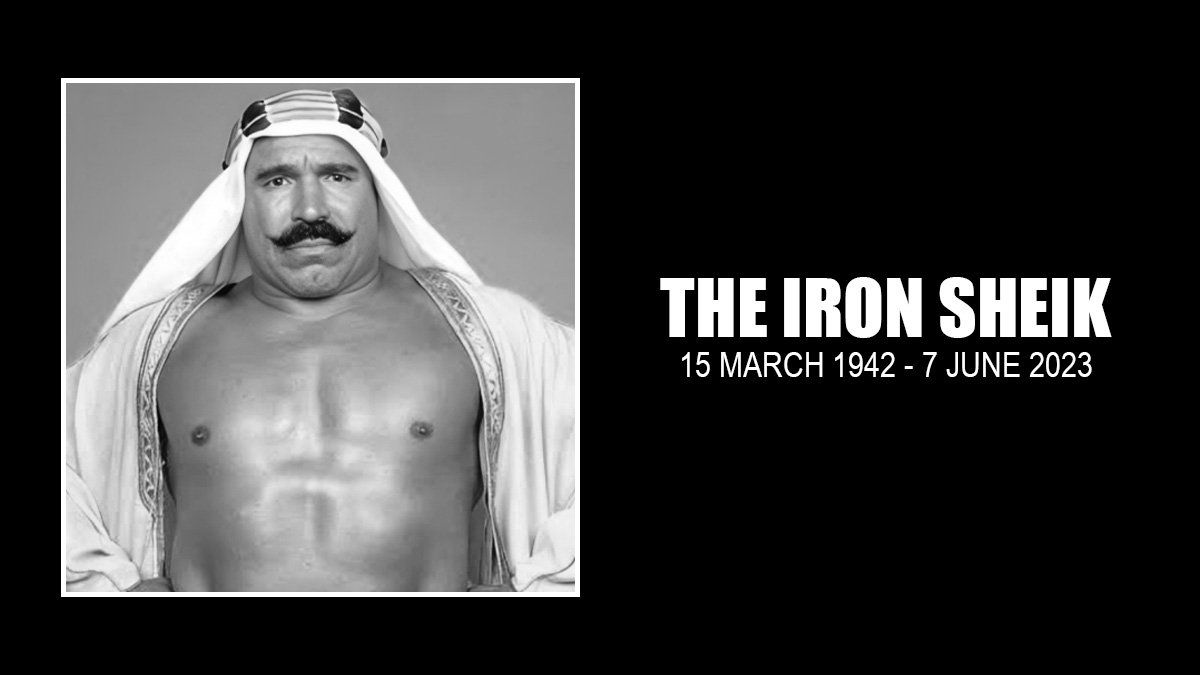

Khosrow Vaziri, the feared Iron Sheik, who became WWF world champ in 1983, has died.

Jian Magen, who worked with his twin brother, Page, on the Iron Sheik documentary, The Sheik, and ran Sheik’s social media, posted the news: “It is with great sadness and sorrow that Page and I make this post. My hero, my mentor, my beloved Papa Sheik has passed away. There is so much more to say however I will need a moment to collect my thoughts.”

Vaziri was 81 years old.

His transformation has been detailed through the years.

Discerning fact from fiction with the Sheik is like trying to separate sausage into its component parts – it’s a painstaking process, and it’s not clear whether you’ll come up with anything worthwhile. Still, it’s worth a shot. The Sheik definitely was an Olympic-caliber amateur wrestler in Iran, starting in Greco-Roman at age 15, when he tipped the scales at 155 pounds. He did serve, apparently, as one of many guards for the former Shah. Contrary to urban legend, he didn’t win any Olympic gold medals. He did not get to the Games; he lost a qualifying round match when Iran was fielding a team for the 1968 Olympics. Nor did he train pro wrestlers for Gagne. But he was AAU national champion in Greco-Roman wrestling in 1971 for the Minnesota Wrestling Club, and worked with some of Greco-Roman wrestlers there who were training for the Olympics. That’s how he hooked up with Gagne, who sponsored the amateur wrestling club.

Greg Gagne started training in a class with Vaziri, Ric Flair, Ken Patera, and Bob Bruggers, and has a clear memory of the facts. “He didn’t know anything about professional wrestling,” Gagne said. “One day, in fact, we went down to the TV studio and we were watching the matches. This is about two weeks into the class. He says, ‘Nobody could beat me. Nobody could ever dropkick me.’ And Verne turned and dropkicked him and knocked him out. He had a little different attitude after that.” Valiant distinctly recalls the meek Vaziri hoping against hope that he might get a chance to change from hanger-on to wrestler. “They had all these guys like Ric Flair and Ricky Steamboat and all these other cats. Then he said to Verne, ‘You think maybe someday I can do like sheik gimmick and make money?’ He did it and he made a fortune. And he’s legit.”

That Vaziri was quiet and reserved.

“You couldn’t get a word out of this guy,” Johnny Valiant said of Vaziri’s days in Verne Gagne’s American Wrestling Association. “He was a very quiet guy. He was 180-some pounds and Verne had him set up the ring and had him refereeing.” Jumping Jim Brunzell added: “He was very, very introverted when he first got in the business. He didn’t drink or smoke and was very religious.”

After working as a midcarder in the AWA for several years under his real name, he headed to New York as Hussein Arab in 1979, just before the U.S. hostage crisis in Iran flared up. Never mind that the Sheik actually was aligned with the Shah, the object of revolutionary Iran’s’ wrath – he had the geopolitical connection to infuriate the fans. “My heat was a natural because I was a real Iranian and you know Ayatollah Khomeini keep the people over there 444 days,” he said. “I was not involved with the politicians but the people didn’t like me carrying Ayatollah picture, Iranian picture. But I just say, that is my country, and I was proud.”

He worked in the Carolinas and Louisiana before returning to the WWF, where he ended Bob Backlund’s five-year reign as champ before dropping the title to Hulk Hogan a month later. He and Nikolai Volkoff, managed by Freddie Blassie, won the federation’s tag titles at WrestleMania I in 1985. As a worker, “he never really caught on to the professional style. Later on, he got big, and he couldn’t move,” Gagne said. Davey O’Hannon felt the Sheik was “kind of a vanilla guy in the ring,” but showed signs of his Greco-Roman training. “He had a suplex for every occasion. He could suplex you from now to next week and not do the same one twice.” But that was secondary to what the Sheik did out of the ring, where he dropped his proper bearings and lapped up Americanization. “What happened to Khosrow is when he got here, it was like a kid on Christmas morning, He said, ‘Holy crap, look at all the stuff I’ve got at my fingertips. All I’ve got to do is, ‘Ptooey, U.S.A’ and wave the flag,’ ” O’Hannon said. “New York did it to him.”

Goulet remembered how the Sheik’s mouth would drop when he encountered women not necessarily covered by a chador, as they were in his homeland. “He was about 31 years old and I don’t think he had ever seen a woman before that. Every time he would see a woman, he would come and he would ask her, ‘Are you a whore?’ ”

That quiet Sheik was long gone by then. When it comes to flapping the gums, well, Captain Lou Albano put it best: “The man is definitely a legend, a vocabulist. When he speaks, the words come out of his mouth. Where they come from, I don’t know. But they come out. Don’t know what he’s talking about, but he talks, he talks, he talks.”

What’s more, the beefy man who would swing heavy Persian clubs over his head for training was a quick-as-a-cat racquetball star, according to Rene Goulet, who knew him in the AWA and the WWF. “He was a helluva of racquetball player. He was playing racquetball up there in Minneapolis with one of the top guys in the country. One time, I challenged him. I used to play racquetball, too. I told him I could beat him. He got pissed and, man, he wiped my ass there. He was really good at that. He was a better racquetball player than wrestler.”

Brunzell had the distinction of wrestling the Sheik in the AWA, the Mid-Atlantic, and the WWF, and diplomatically said he thought Vaziri’s character changed when he got into the goodies in the fast-paced Northeast. “He sort of sampled various products and it completely changed him. He was like a Dr. Jekyll and My. Hyde.” What Brunzell was referring to, among other incidents, was a May 1987 episode when the Sheik and Jim Duggan – his arch-rival at the time – were busted for drug possession in New Jersey. The charges were dropped after the Sheik, who had been found with small amounts of marijuana and cocaine, completed probation and underwent drug testing.

Volkoff had firsthand experience with the Sheik’s wayward ways when he woke up in a cloud of smoke in a Toronto hotel room one night. “The drugs. It was the Sheik and his party there. I told him, ‘Sheik, you, what’s wrong with you?’ ” But Volkoff got him back in spades – sharing a big bed one night, the big Russian simulated passing gas. The Sheik immediately got up and took a shower. “He is Muslim … he has to be clean, you know?” Volkoff said. A couple of hours later, Volkoff pulled the same trick, same result, same shower. “I love the guy, but Sheik likes to party, likes to drink,” Volkoff laughed. “There is nobody like him.”

The Sheik returned to the WWF in 1991 as Col. Mustafa, acting as a second to American turncoat Sgt. Slaughter, and was inducted into the WWE Hall of Fame in 2005. He’s now better known for his obscene, and off-the-wall rants against Hogan, Gagne, Vince McMahon, Volkoff, and others, though he suffered a personal tragedy in May 2003, when his 27-year-old daughter Marissa was found strangled to death in a Georgia apartment; her boyfriend told police he did it. “He keeps screaming her name out. And he’s still recovering from his surgery. So he hurts from head to toe,” Vaziri’s wife Caryl told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

The redemption of the Iron Sheik came, in part, through the Magen twins in Toronto. Their father, Benjen, was a competitive Iranian table tennis player, and knew Vaziri from their homeland. When Vaziri would wrestle in Toronto, he would visit the Magen household.

“We took him from being a drug addict, cleaning him up, to making him a social media icon. Indirectly, he has had everything to do with the success of our business,” Jian Magen said in 2013, detailing work on the documentary, The Sheik, which was a six-year project. “The first three years, he was addicted to crack cocaine. We couldn’t do much with the footage, other than expose him. So we kept on trying. He cleaned up one night here in Toronto, when we stopped everything, and said we’re not going to be able to work with him anymore. He had a mild heart attack and he was in the hospital for four days here in Toronto, getting sober. At that point, his life turned it around — he turned it around.”

The was the Magens who made Sheiky-baby a huge presence online, from the outrageous tweets to the surprise appearance at the Grammy Awards.

The Sheik documentary and a recent A&E Biography on him have helped tell Vaziri’s tale in greater detail. There was a book written about Vaziri by Keith Elliot Greenberg, but it was shelved indefinitely by WWE. ECW Press did make up review galleys before it was spiked, and a few copies did make it out into the world.

The Sheik’s Twitter account signed off the news appropriately:

To his family, friends, and all those who were touched by his larger-than-life presence, we offer our deepest condolences. May you find solace in the knowledge that The Iron Sheik’s legacy will forever be cherished and celebrated. Rest in peace, dear Sheik, and thank you for the memories.

RESPECT THE LEGEND.

Vaziri leaves behind his wife of 47 years, Caryl, and children, Tanya, Nikki and Marissa.