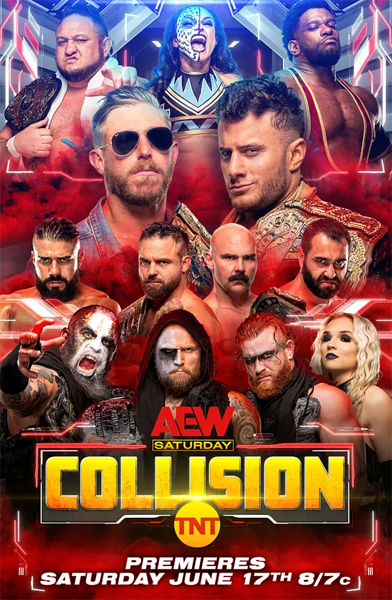

On Saturday, June 17th, AEW will air the first episode of it’s new show: Collision. The show will air live on TNT, joining Dynamite and Rampage as appointment viewing for die-hard wrestling fans.

Details are still emerging but it looks like Collision will be positioned as a full-fledged AEW broadcast, while Rampage will officially be demoted to a developmental show like WWE’s NXT (some might say this has long been the case, but clarity is a good thing). It also looks like Collision’s network platform will mean the end of AEW’s YouTube shows, Dark and Elevation, which have already been cancelled.

I’m all for more wrestling on television but let’s consider the reality of a Saturday, 8 PM timeslot in a streaming universe. In 2021 Nielsen reported an aggregate of 8 million U.S. viewers for broadcast television on a Saturday evening. Forget cable outlets like TNT or TBS, this number caught the four major networks ABC, CBS, NBC and FOX. Keep in mind this number also reflected viewership at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic when many of us had little to do on weekends but watch TV. In the U.S. today, Saturday is the lowest rated night of the week and Saturday evening is considered a “graveyard slot” by programmers, meaning there are fewer people watching TV compared to other days of the week and times of day.

This wasn’t always the case. Saturday nights used to be big business for broadcasters. Shows including Gunsmoke, All in the Family, the Bob Newhart Show, the Facts of Life and the Golden Girls all commanded audiences in the tens of millions. This continued through the 1990s with shows like Walker, Texas Ranger, America’s Most Wanted and COPS.

But then a funny thing happened; whether audiences started tuning out or networks lost interest in the face of cheaper alternatives to first run programming, U.S. networks have aired a steady diet of movies, reruns, burned-off cancelled series and infomercials for almost 40 years. The last network gasp happened in 2001, with NBC’s failed XFL run.

From TNT’s perspective the stakes are relatively small but from AEW’s viewpoint the opportunity is significant. Collision’s Saturday night spot gives AEW a chance to continue to build its brand in front of a smaller audience but one with arguably less first-run programming competition. I’ll leave how streaming services like Netflix and Disney+ have decimated network TV viewership to actual media writers.

I imagine it’s also a time slot that draws outside the usual, key and all-important 18-35 male demographic that wrestling has chased since the Monday Night Wars. My guess is that 8:00 pm on a Saturday will attract more kids (older kids but still kids) who never heard Billy Red Lyons say “Dontcha dare miss it!” or Dusty Rhodes lament George South’s failure to hit the “pay window” after a “clubberin”. A Saturday night slot may give these kids a chance to make their own memories, investing in the characters, storylines and matches that will help make them fans.

The time slot may also capture older viewers who tuned out when Vince McMahon undertook his national expansion, bouncing local wrestling shows from the airwaves and leaving them disaffected with WWF’s more soap-opera oriented product; or who left in the late 1990s when wrestling got edgy and disapproved of the sex and violence that drove the Monday Night Wars. AEW has a chance to lure these lapsed fans back, too. Harkening back to my own experience, the best of all worlds may see AEW capture both generations at once, creating memories within families and building a new generation of fans if AEW is smart with how it uses this new slot.

Saturday nights have long been big business for wrestling. Before pay per views and premium live events and all manner of merch, TV wrestling was an infomercial designed to attract people to come see the fights live. TV stations were quick to capitalize on the cheap programming that pro wrestling offered and promotions were eager for the platform to put TV viewers behinds in arena seats. Depending on where you live and the era in which you grew up, you likely have your own Saturday night wrestling memories.

WWWF broadcasts were a fixture on iWWOR TV in New York going back to the 1970s, airing late Saturday night. In 1975 media executive and future Chicago White Sox owner Eddie Einhorn saw the success of WWWF’s local TV show and hatched an ambitious plan for the first national pro wrestling company. Einhorn amassed a million dollar bankroll and joined forces with Pedro Martinez as the wrestling ‘inside man’. He named his venture the International Wrestling Association (or IWA) and offered lucrative standardized contracts to his talent. IWA signees included Ernie Ladd, Ivan Koloff, Lou Thesz, Ox Baker and the Wild Samoans. Einhorn also signed reigning, defending WWWF tag team champion Victor Rivera-a move that would later see Rivera blackballed from wrestling. The IWA’s first champion would be Mil Mascaras.

Einhorn’s legitimate media background allowed him to sign syndicated TV deals across the US, tethering the IWA to a list of sports properties that Einhorn already held. It was a shrewd move which led many stations to jettison other wrestling companies from their airwaves in favor of Einhorn’s not-so-small package. Thus, the IWA replaced WWWF Saturday night wrestling in New York-the Federation’s home turf-overnight; exiling WWWF broadcasts to the Spanish-language Telemundo station.

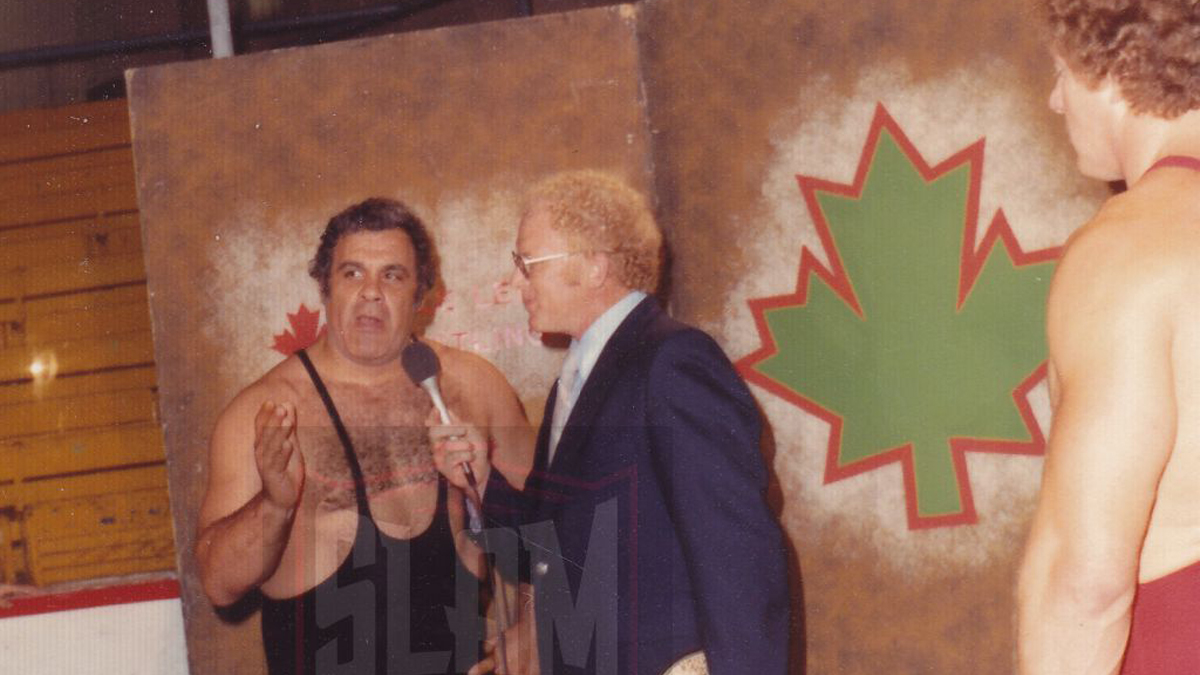

Angelo Mosca is interviewed on Maple Leaf Wrestling by Billy Red Lyons as Dewey Robertson looks on. Courtesy: Terry Dart, Slam Wrestling.

Moves like this failed to endear Einhorn to other promoters. Following anti-trust lawsuits and talent defections due to pro wrestling’s anti-competitive nature, the IWA shrunk from an internationally syndicated brand to a small loyal outfit. It would go out of business in 1978.

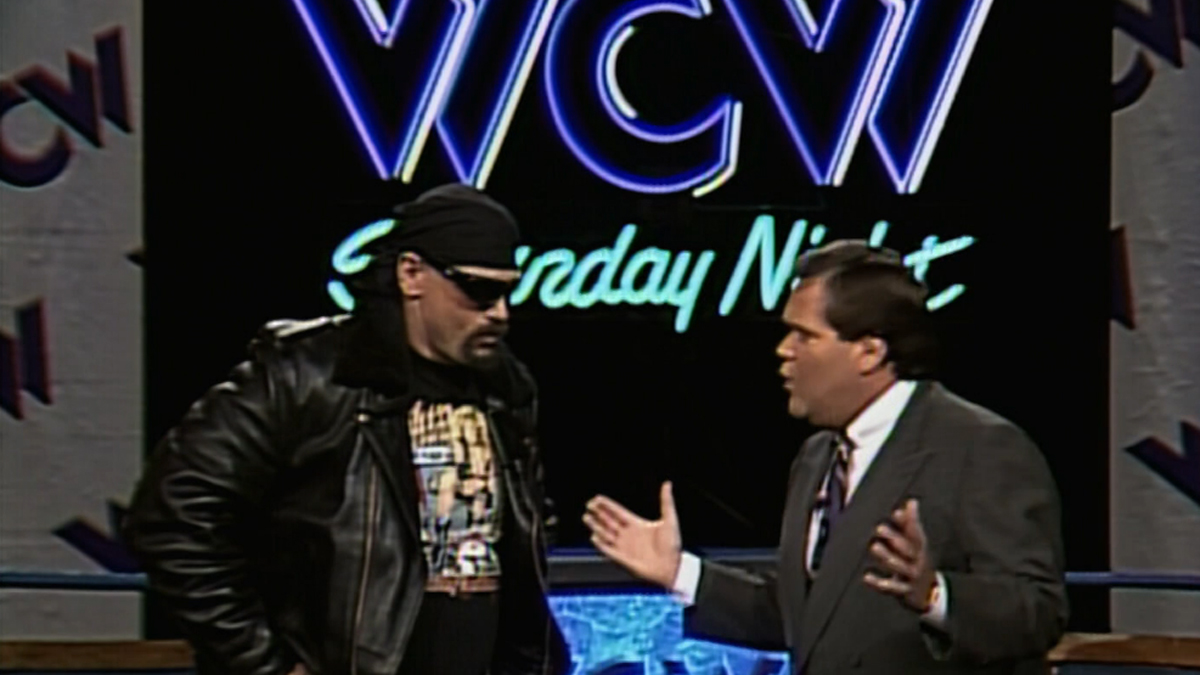

The grandaddy of TV wrestling (or the Mothership, if you will) was WCW Saturday Night, which aired on the station that would become TBS starting in 1971. Saturday Night started with WCW’s predecessor, Georgia Championship Wrestling. It was a fixture on Turner’s networks and Turner felt a degree of loyalty to the genre, since cheap ‘wrasslin’ drew regular eyeballs to his struggling new stations. Younger fans (OK, not so young. The show went off the air in 2001) may remember Saturday Night as a less relevant show featuring mid-carders in squash matches against enhancement talent but in the days before Monday Nitro, Saturday Night was the place where stories were told, titles changed hands and feuds were hyped.

Two key points: WCW Saturday Night was a fixture from 6:05 to 8:05, notable for being a kid-friendly time slot (especially compared to AEW’s 8:00 PM slot) and for TBS’ and Ted Turner’s signature off-kilter scheduling, which he used across networks in the belief that staggering his broadcast times would make viewers less likely to change the channel.

WCW’s modern version of its Saturday Night wrestling program premiered in April, 1992 but it’s origins lie in Georgia Championship Wrestling and Jim Crockett Promotions, as far back as 1971. By virtue of its presence on WTBS as that station went national, GCW became the first NWA member to broadcast across the U.S. This upset other NWA members, which GCW tried to mollify by claiming it was only using local talent. GCW’s TV series was hosted by Gordon Solie and taped in-studio before a small live audience. The show adhered to a now-familiar TV wrestling template: matches, promos and disputes between performers. In 1982 Georgia Championship Wrestling renamed itself World Championship Wrestling at Ted Turner’s request, reflecting his desire to build a national media empire.

The show would be an integral part of one of the biggest moments in wrestling nerd history: in 1984 WWF’s owner Vince McMahon bought a majority stake in Georgia Championship Wrestling, along with it’s timeslot on WTBS (something Tony Khan might have considered when buying Ring of Honor, but I’ll get back to that). On July 14, viewers were shocked to see McMahon on screen offering WWF matches. This broadcast, which took place without warning before an audience of entrenched Southern wrestling fans, would become known as ‘Black Saturday’. The entire GCW promotion went out with a snap of McMahon’s fingers.

The WWF’s tenure in Georgia would prove short-lived. McMahon had promised Turner that he would continue producing original content for his new show but failed to deliver, airing clips of matches from WWF’s other syndicated broadcasts instead along with occasional squash matches. Turner would counter McMahon’s broadcast by inviting Ole Anderson and Bill Watts to air their respective programs on his network in addition to McMahons’, where McMahon had presumed exclusivity but failed to add it as a term of his contract with Turner. McMahon started losing money and eventually sold his timeslot on TBS to Jim Crockett Promotions in 1985. Crockett would consolidate his promotion with Anderson’s (successfully) and later Watts’ (less successfully).

The rest, as they say, is history.

WCW Saturday Night offers a lesson for AEW, which between Dynamite, Rampage and now Collision, will be producing five hours of first-run network wrestling TV a week. In the wake of a three-hour Nitro and two hour Thunder, Saturday Night faded intro irrelevance. Despite a bloated roster and an army of bookers, WCW just had too much time to fill and too few ideas about how to fill it. The car crash nature of Nitro and Thunder plots conditioned WCW’s audience to expect similar breakneck action across its platforms, which the likes of Lightning Foot Jerry Flynn, Hardbody Harrison and Jim Powers just couldn’t provide.

I’m a little concerned for AEW in this respect. AEW has a reasonable formula when it comes to Dynamite. Shows usually feature one or two very good matches, plus an excellent promo or two. There’s still a bunch of filler (although this could be remedied for folks like myself by airing more or longer matches, especially when many talents appear to be off TV for extended periods of time). My hope is that the Saturday show will give more talent room to breathe, although Rampage already feels like an afterthought. It features tons of great wrestlers in often rushed matches of little consequence. I don’t know if Tony Khan is considering it but I think he needs to expand his writing/booking staff so the extra time is meaningful.

Jesse Ventura and Jim Ross on the first episode of WCW Saturday Night. Courtesy: WWE Network.

I think the biggest challenge with AEW creatively is the mid-card. It seems like they haven’t quite figured out yet how to convincingly elevate talent or keep them in that mix. I’m surprised how little main event exposure performers like Miro and Malaki Black have had (although Miro is supposedly booked for the Collision premiere). I thought they were badly misused in WWE but they don’t seem to have done THAT much more in AEW. I would hope that they and others would have a bit more space to show just what they can do across a few more blocks; showcasing deeper move sets and filling time with more creative, cinematic segments.

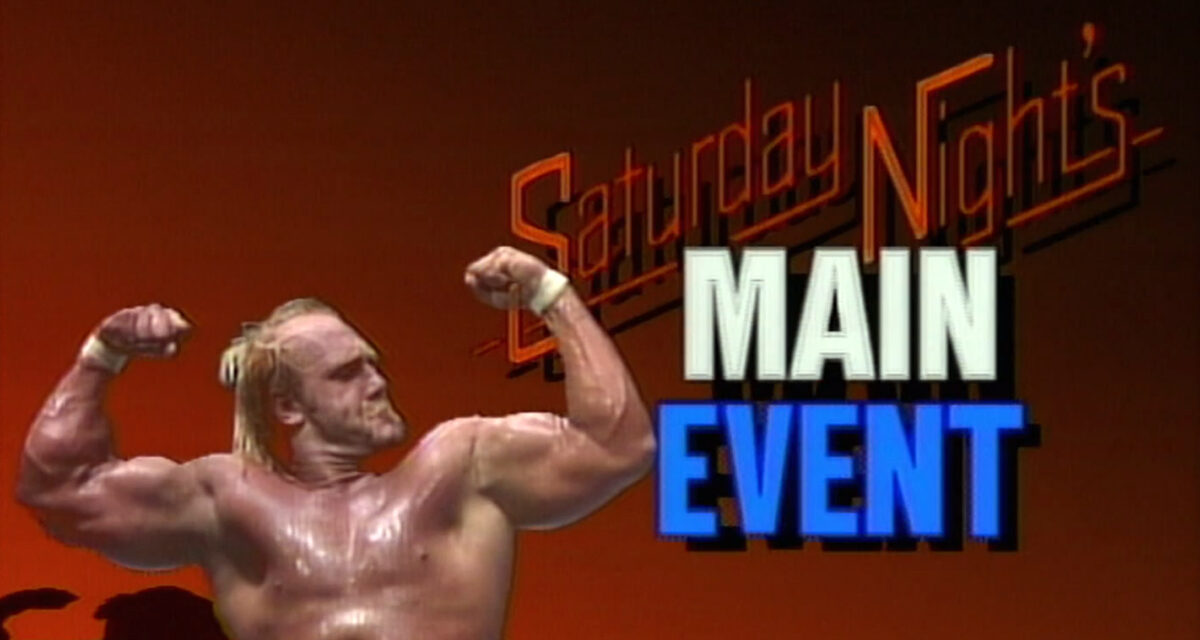

Less frequent but perhaps with greater audience penetration and pop culture relevance, Saturday Night’s Main Event was launched by the WWF in 1985 as a periodic replacement for Saturday Night Live (which would air three weeks out of four during the TV season). It ran for 29 episodes between 1985 and 1991 on NBC, then twice on FOX in 1992. NBC would bring the show back between 2006 and 2008 for five more episodes.

Saturday Night’s Main Event was notable as one of the main instances of professional wrestling appearing on a commercial network well after the sport’s heyday when television was born in the 1950s. It was a critical part of the Rock and Wrestling fad and gave viewers a rare chance to watch compelling matches between major stars, rather than the squash matches and promos that made up other syndicated weekend broadcasts. That said, reviewing the early cards few of these matches went ten minutes. It was a different time, and McMahon was in the process of reorienting pro wrestling away from the in-ring action emphasized by the likes of WCW (in it’s GCW and JCP days) and towards storylines and skits.

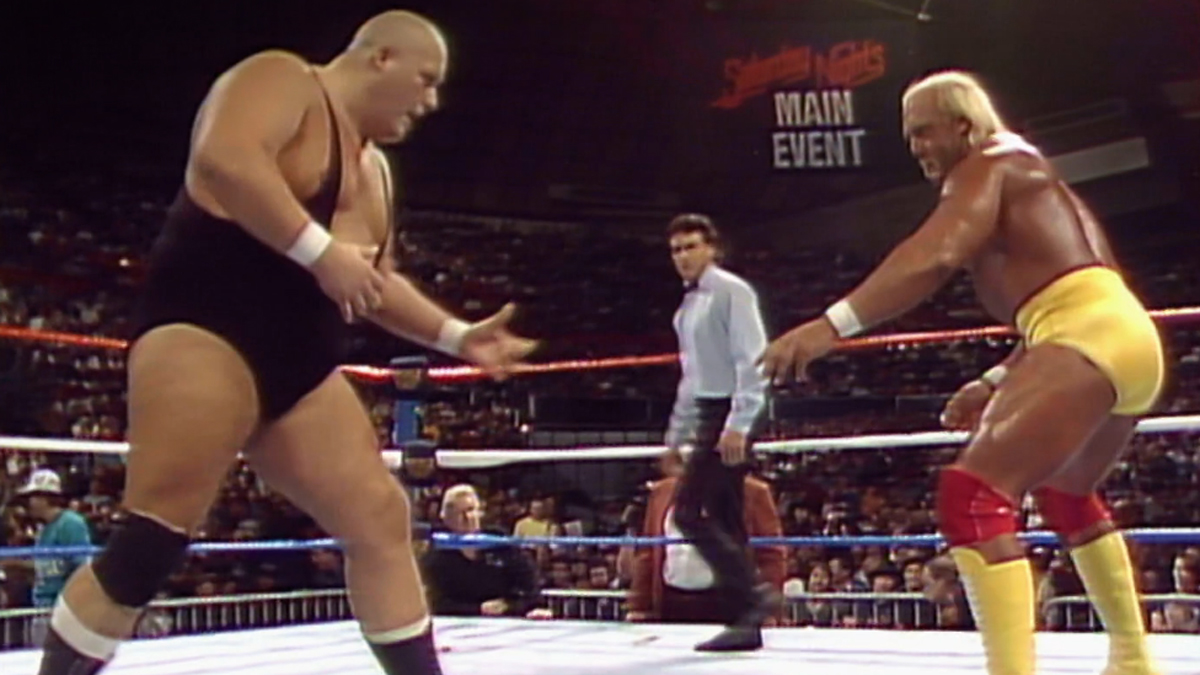

At a time when WWF Champion Hulk Hogan rarely appeared on free TV, Saturday Night’s Main Event would be where fans like myself got to see him fight (I went to several cards at Maple Leaf Gardens but would not get to see the Hulkster until his WrestleMania X8 match against the Rock). It was also unique in that, given it’s late start, the ‘main event’ would often go on early, with the last match left to the likes of the Young Stallions, Playboy Buddy Rose, Lanny Poffo or Boris Zhukov.

Saturday Night’s Main Event is so ingrained into wrestling fans’ consciousness that WWE recently brought the name back to promote weekend house shows.

Saturday Night’s Main Event reflected NBC executive producer Dick Ebersole’s close relationship with Vince McMahon, especially after Ebersole noted the high ratings for two WWF specials on MTV. It was a smash hit in its early years. In March, 1987 it earned an 11.7 rating which remains untouched in that time slot. It was so successful that it would spawn a series of Friday Night broadcasts, called “the Main Event”. The First Main Event would see Hulk Hogan lose his championship to Andre the Giant thanks to “evil twin” Earl Hebner, who between this and Survivor Series some years later may just be history’s greatest monster.

More recently, promotions have used the Saturday night ‘death slot’ to carve out reputations as being part of a more violent or risqué subculture. ECW’s flagship Hardcore TV show was syndicated to markets across the US between 1993 and the promotion’s death in 2000. While aspects of ECW’s broadcasts have aged badly, the central idea that anything could happen in a broadcast, highlighted by a lack of structure or reliance on traditional main event booking made it must-watch TV at a time when the WWF and WCW were often predictable and boring. ECW was able to leverage late night weekend timeslots to air it’s adult content without censorship, and fans grew rabid. Int it’s home base of Philadelphia ECW aired Hardcore TV during the week, but Orlando, Pittsburgh, Los Angeles, Virginia, Louisiana all aired the show late Saturday (New York and other markets would air Hardcore TV on Friday late nights, which is close enough for my purposes).

Seeing ECW’s success with a more grown-up pro wrestling product, the WWF would attempt it’s own adult-oriented Saturday night broadcast. Shotgun Saturday Night had a short run from 1997-1999 but featured a number of innovations. As first conceived, Shotgun Saturday night aired in a late timeslot, shot on location at a series of New York nightclubs. The WWF’s idea of edgy TV, the debut episode saw Goldust’s valet Marlena remove her top (with her back to the camera) during a match between Goldust and the Sultan. The most impressive debut saw a returning Brother Love dress the headbangers tag team in nun outfits as the Sisters of Love. The nightclub theme didn’t last and the show would soon be taped around Monday Night Raw. Still, it presaged WWE’s move to raunchier content as part of the Attitude Era.

Less historically important but dearest to my heart is Maple Leaf Wrestling, which was produced out of my hometown of Toronto and neighboring city Hamilton, Ontario. Taking its name from the wrestling promotion run by Frank Tunney (uncle of future figurehead WWF President Jack), it ran from 1930 until 1984 when it was absorbed into the WWF as part of the latter’s national expansion, although it kept operating under the WWF’s auspices until 1986. After the WWF’s takeover, the title “Maple leaf Wrestling” would continue to be used for WWF’s Canadian TV program, which is where I come in. The show aired on Hamilton’s CHCH television station at 7:00 PM on Saturday night. It was originally hosted by Angelo Mosca and Jack Reynolds, and in later years featured frequent cut-outs to Ontario wrestling legend Billy “Red” Lyons, who’s catchphrase is still used in my house to the confusion of my children. For what it’s worth, Billy Red told us not to miss the next broadcast and we didn’t. Maple Leaf Wrestling was appointment viewing in my house.

Hulk Hogan and King Kong Bundy throw down on Saturday Night’s Main Event. Courtesy: WWE Network.

TV tapings were held in Southern Ontario for a while, then replaced by standard syndicated matches with a ‘main event’ tacked on at the end. This ‘main event’, called by Gorilla Monsoon and heel commentators like Bobby Heenan or Jesse Ventura was often a preliminary match from a recent card at Toronto’s Maple leaf Gardens. The effect was jarring: the syndicated squash matches featured WWF state of the art graphics and lighting and camera work and sound. The main event was often garishly lit and the camera work shaky, with music barely audible over the crowd noise. Monsoon would hype the viewer promising a ‘main event anywhere in the country’ only for the likes of Mario Mancini, Jose Luis Rivera, a pre-Genius Lanny Poffo or SD Jones to take on Barry Horowitz or Steve Lombardi or Jose Estrada or Pete Dorchester…or maybe one of the above would fight a local talent even lower on the independent contractor pecking order. Once in a while, a bright spot for in-ring action when a new superstar would debut in a squash. Maple Leaf Wrestling gave me my first look at the Ultimate Warrior, or a strange result like Tugboat beating a recently-debuted Kane the Undertaker in a body bag match.

Occasionally the magic of a house show translated well. Gorilla Monsoon had a freer hand on commentary and was wont to call out what he saw as poor wrestling. Apart from problematic Pearl Harbor and “Pat Patterson School of Self Defence” comments, Monsoon would roast talent he thought worked lazily, or who didn’t look the part. Veteran Montreal wrestler Richard Charland had a shot on one broadcast. Monsoon’s repeated digs at his physique (he was bulky, but not a bodybuilder) and lack of urgency in hitting his spots made it clear we wouldn’t expect him back.

The Killer Bees featured in one main event, only Jim Brunzell wore his Masked Confusion mask through the whole contest. Masked Jim Brunzell was also Black. And the team still did the full Masked Confusion gimmick. And it worked. I think NXT blew a huge opportunity by not pairing up Apollo Crews with PAC or Murphy in a variation of the gimmick which I would call the Murder Hornets-they’d work the masked switcheroo and the referee and opponents wouldn’t be able to tell the difference because of the Hornets’ similar builds. Vince Russo, I’m comin’ for ya!

Maple Leaf Wrestling wasn’t on the level of WCW Saturday Night or WWE’s own main event broadcasts, but as a little kid the 7 PM start time marked peak weekend. Scrubbed and pyjamaed after a day of play, stomach filled with pizza or Peking ravioli from the local Chinese food place, I remember the show as better than it was. Sharing the couch with my dad (or a very patient babysitting grandmother) it was a weekend ritual that I still value. I wouldn’t be a fan today if not for Saturday night wrestling.

But most of you aren’t here for my nostalgia trip. Next column, five things that I think will help make Collision a success and help make Saturday night wrestling a tradition once more.

RELATED LINK