In a recent interview, National Wrestling Alliance (NWA) owner and The Smashing Pumpkins (and Zwan) frontman Billy Corgan noted that he is not a fan of entrance music used in wrestling. While he acknowledged the importance of music to the overall presentation of the modern product, he noted that much of the music we hear weekly is sub-par and that the costs associated with licensing recognizable popular songs are prohibitive to all but the biggest players in the game.

Piecing together an accurate history of any part of pro wrestling is a challenge, given the prevalence of kayfabe and the often fractured nature of the territory system, but conventional wisdom has it that the use of entrance music coincided with the advent of televised wrestling in the 1950s. Women’s champion Mildred Burke and Gorgeous George have competing claims to being the first wrestlers to employ music, although George’s “Pomp and Circumstance” (later used to great effect by Randy Savage) is by far better known. Until the boom of the 1980s which saw wrestling wedded to popular culture and MTV’s version of rock ‘n’ roll, music would be used only where it particularly suited an existing character. For example, Sgt. Slaughter sometimes employed the “Marine’s Hymn”. Slaughter also takes credit for introducing the broader idea of playing wrestlers into the ring to Vince McMahon at the beginning of WWE’s national expansion…but the wrestling so many of us know and love established many of its conventions in the 1980s.

Gorgeous George.

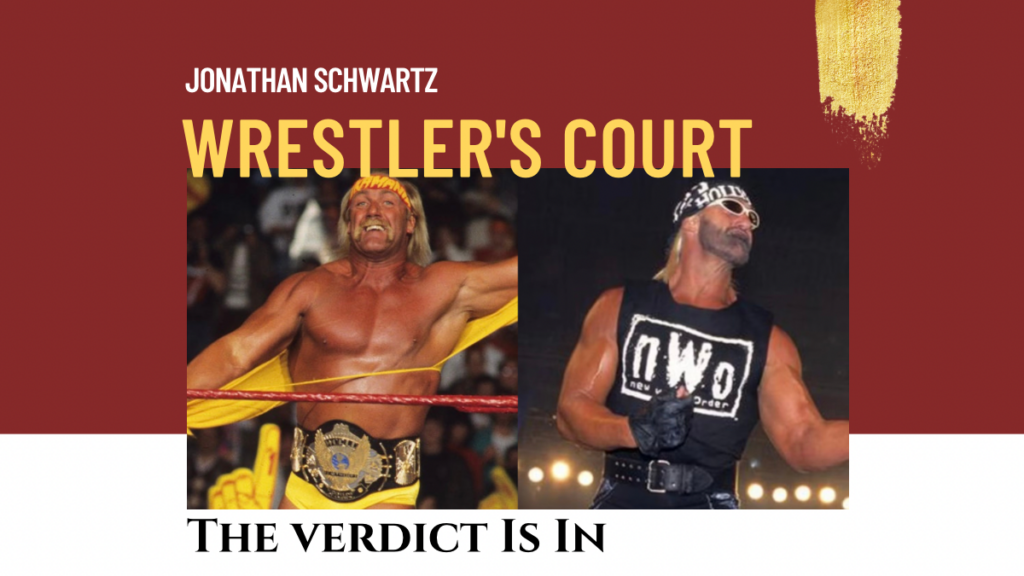

Hulk Hogan’s use of “Eye of the Tiger” from the Rocky movies predated his (then) WWF arrival and was part of his run almost to the top of the American Wrestling Association (AWA)…and was a part of his near-mythical entrance performance until Jimmy Hart’s “Real American”, which had the advantage of being produced in-house with no royalties required, was used instead.

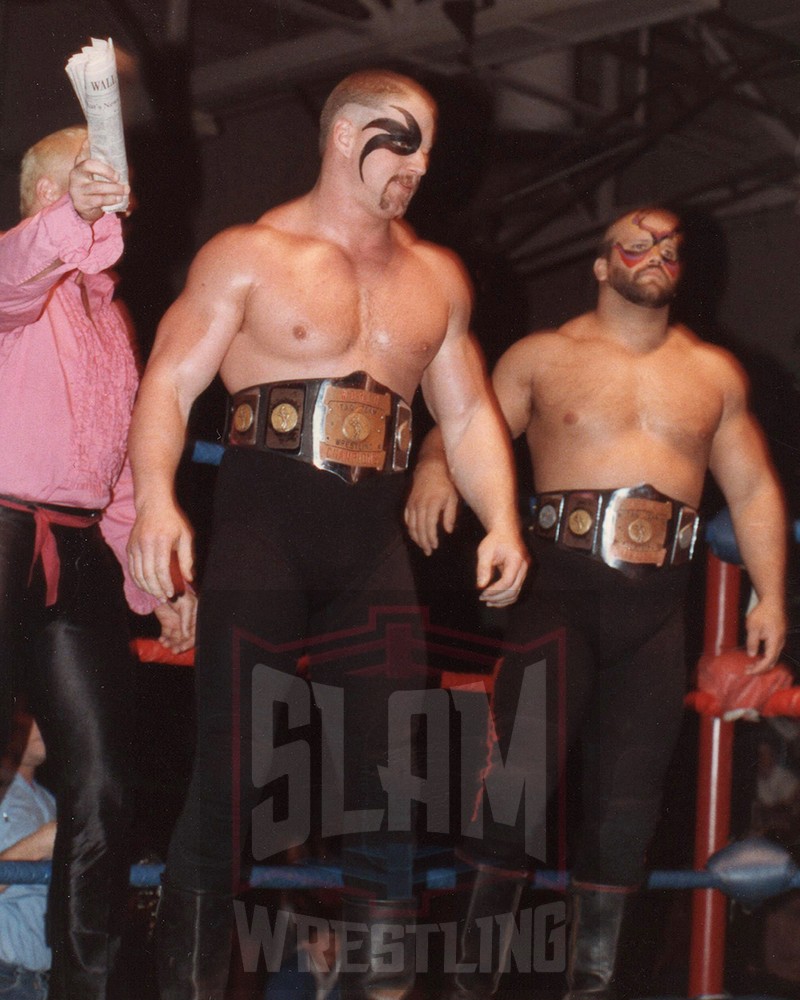

Outside WWE, Ric Flair became synonymous with the classical piece “Also Sprach Zarathustra, Op. 30”, composed by Richard Strauss (really, classical music has become an essential part of the heel’s musical canon; including Daniel Bryan’s run with Wagner’s “Flight of the Valkyries”, Damian Sandow’s use of Handel’s “Messiah” and a pre-D-Generation-X Hunter Hearst Helmsley’s employment of Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy” when generic harpsichord failed to pop the crowds), and the infamous Road Warrior pop was set to the opening riff of Black Sabbath’s “Iron Man”.

Precious Paul Ellering presents the Road Warriors, Hawk and Animal, for AWA action. Photo by Joyce Paustian

Some argue that other territories beat WWE to this punch. Kerry Von Erich’s use of Rush’s “Modern Day Warrior” in World Class predated the widespread use of music in WWE, along with the Missing Link’s appropriation of “Bang Your Head”. In Bill Watts’ Mid-South Wrestling Junkyard Dog would come to the ring to Queen’s “Another One Bites the Dust” (which would also follow him to WWE, until replaced by another in-house composition, “Grab Them Cakes”, which sucked). I’ve never quite captured the timeline but controversial journeyman Chris Colt was also an early adopter of many modern wrestling tropes. He borrowed liberally from subcultures he encountered along the way, Colt would enter the ring to Alice Cooper’s “Welcome to My Nightmare”; eyes painted black like vintage Alice, pierced and wearing chains and leather and sometimes more Nazi-inspired regalia than would make one feel comfortable. Colt lived a rock ‘n’ roll lifestyle, and like Judas Priest’s Rob Halford or Hellraiser’s Clive Barker, drew inspiration for his gimmick from the hardcore LGBTQ scene of which he was a part.

One of the best early uses of entrance music and its integration into wrestlers’ characters, was the Fabulous Freebirds. The Freebirds rose to prominence using that Lynyrd Skynyrd song, before transitioning to the so-bad-it’s-good “Badstreet USA” and the execrable “I’m a Freebird (And What’s Your Excuse)” during their latter WCW run. While the Freebirds and their gimmick would likely not play nearly as well today as they did in the early-mid 1980s, their influence on the performance parts of pro wrestling still bears note. They also deserve mention for one of the best, albeit brief, tie-ins between wrestling, music and film, as part of the beginning of the movie “Highlander” where their entrance with a headbanging Terry Gordy and gyrating Michael P.S.Hayes plays out against a parking lot battle to the death that makes William Regal and Fit Finlays’ look tame.

The Freebirds.

Since entrance music became widespread during the 1980s and 1990s, it has become as much a part of a wrestler’s character as his or her move set, gear, merchandise or catchphrases.

The opening notes of a wrestler’s theme can cause a crowd to explode-I’d argue many songs were designed for that initial pop, especially those with a distinctive riff (CM Punk’s Cult of Personality, Hollywood Hulk Hogan’s Voodoo Chile (Slight Return)), sound effect (Steve Austin’s broken glass or Razor Ramon’s squealing tires), or voice clip (“If you smeeeeeeelllllllllll what The Rock….is….cooking”). The vast majority of music composed specifically for entrance themes treats the body of the song as incidental; either a version of a driving guitar-focused instrumental, a close-enough soundalike to an existing popular song that still keeps the intellectual property lawyers at bay, or a generic rocker with some angry dude singing about how his guy will beat up the other guy. As pro wrestling seeks to diversify its audience rap has become increasingly common-and not just for more stereotypical characters like R Truth (who raps himself to the ring), Cryme Tyme, Men on a Mission or Hit Row. Taz(z) moved on to a Cypress Hill variant of “Rock Superstar” and his son Hook now enters the ring to an Action Bronson joint in AEW. Jack Swagger used a Rage Against the Machine cover band. AJ Styles’ theme is a DMX soundalike, while Austin Theory’s “A-Town Down” is apparently performed by Def Rebel. Heck, John Cena released a whole rap album that went to #15 on the Billboard 200 during his ‘freestyle’ phase.

A change in music often signals a character’s move from face to heel, or vice versa. Edge, who used Alter Bridge’s “Metallingus” since he debuted his “Rated R Superstar” persona overhauled his persona to a darker version of Chris Jericho’s run as a delusional, suited, Nick Bockwinkel-style heel (really, if Chris Jericho and his friend Don Callis as the Jackyl had a baby, it would be that version of Edge). This change included a shift to a slower, more foreboding Alter Bridge track which stayed with Judgment Day after Edge was kicked out (though individual Judgment Day members retain their own themes). Edge’s dalliance with that stable also involved getting rid of his distinctive pyro, hyped-up entrance mannerisms, and a shift away from rock ‘n’ roll leather jackets and sneakers …in other words, to make a conquering hero a heel, WWE has stripped him of everything that made Edge fun to watch. Of course, Edge’s run was limited and somehow the group became more fun without him, which led to a year-long feud between the old boss and new boss Finn Balor.

The Judgement Day.

When CM Punk fought MJF in a blood-soaked dog collar match in AEW the two men communicated the seriousness of the contest with a musical double-turn. MJF sought to psych out Punk by entering the ring to Punk’s own “Cult of Personality”, while Punk dug deep into his Ring of Honor roots with his old theme: Miseria Cantare by AFI. The use of music played directly on the real, historical grounding of this feud and provided a great soundtrack.

As usual, WWE and AEW provide an interesting contrast. Except for rare circumstances, WWE produces or licenses most of its’ music in-house. For decades this meant a variety of styles invoked first by Jimmy Hart (who would later contribute music to WCW and TNA-and who is probably one of the all-time most useful support players in the business) and later by Jim Johnson (whose contributions merit inclusion in WWE’s Hall of Fame). Johnson captured styles as varied as rock, rap, country and metal, and collaborated with any number of ‘legitimate’ musicians in capturing superstars’ signature sounds. This is despite not being a wrestling fan himself. In his wake, WWE used corporate music outfit CFO$ for two years…which did bring a more modern sound to a new generation of talent. More recently, WWE has turned to Douglas J David and Ali Dee Theodore, and new themes feel increasingly generic, identifiable primarily by sound effects or voice clips rather than signature styles or instrumentation. If you’re a music fan, this approach is probably a snooze, but it has the advantage of keeping key parts of talents’ presentation (like ring names or catchphrases) within WWE’s IP wheelhouse. From a talent’s perspective, it makes a tougher road to retain their identity and fan interest, but it’s an effective safeguard. The Hardys arguably owe most of their notoriety to WWE, but between using their actual names and generic, easily licensable music (which was produced outside of WWE’s auspices), they were able to leverage a hometown pop in Jeff’s first match in AEW. If you’re a fan of music spotting, try tracking down an old Kids in the Hall sketch where Scott Thompson’s Francesca Fiore sashays through a sketch to Harlem Heat’s old theme.

For completeness’ sake it’s also worth noting Dale Oliver’s contributions to Impact Wrestling and Harry Slash and the Slashtones, who produced Extreme Championship Wrestling’s (ECW) in-house music (including their truly banging TV show’s theme).

Tommy Rich and Tracy Smothers of the Full-Blooded Italians in ECW. Photo by George Tahinos, https://georgetahinos.smugmug.com

AEW has taken the route employed by old school promotions and ECW in using actual songs for some of its’ talents…the key difference being that AEW is most likely paying the exorbitant licensing fees that gave Corgan pause, and which ECW owner Paul Heyman allegedly ignored figuring there was never enough mainstream attention paid to his product to worry about it.

What’s interesting is that AEW’s themes are a combination of in-house (Adam Cole, Kenny Omega when not teaming with the Young Bucks to Kansas’ “Carry on my Wayward Son”) and pre-existing, whether the talent who uses them is at the top of the card like Punk when he’s around, or somewhere in the middle like Jungle Boy (“Tarzan Boy” by Baltimora”), Hook (“The Chairman’s Intent” by Action Bronson), Toni Storm (“Barracuda” by Heart), Orange Cassidy (“Where is my mind” by the Pixies and now “Jane” by Jefferson Starship) or Ruby Soho (that one’s a gimme). AEW talent aren’t subject to the same restrictions against performing elsewhere as WWE’s independent contractors, so it may be that the office feels they have less to lose…and grounding the fictional world of AEW rivalries and conflict resolution in real-world music helps grow their presentation up a bit. I suspect AEW’s nods to classic rock across the roster is also meant to make their talent more relatable to an older audience.

Hook and Action Bronson at AEW All Out at the Now Arena, in Hoffman Estates, Illinois, Sunday, September 4, 2022. Photo by George Tahinos, https://georgetahinos.smugmug.com

Corgan is right about entrance music in general. With the exception of a few visionary performers and promoters, pro wrestling often falls well behind the pop culture curve. For the last decade or so it has been a last bastion of early 2000’s rap-rock and nu-metal, droning instrumentals or sound effect-laden samples without much context. But there are a few bright spots, particularly on the independent scene where people play a bit faster and looser with copyright laws. I can only hope that more wrestlers and organizations start putting their ears to the ground and realize how much more interesting music brings to their products.

But seriously…without going into specifics, go find an Asylum match on the Ontario Indies and tell me he hasn’t picked the perfect song.

RELATED LINKS