Many years ago, when I started law school, it was impressed on me that there is often a big difference between that which is “right” and that which is “legal.”

Since the end of December former WWE Chairman Vince McMahon has returned from his retirement/exile and come back to the helm of his company with a mandate to sell, sell, sell.

This has left many wrestling fans uneasy, me among them. McMahon saw a sexual misconduct scandal which allegedly involved using company funds to pay “hush money” to subordinates with whom he entered inappropriate workplace relationships as something that would “blow over.” Allegations that these affairs took place despite a clear imbalance of power and apparent questions about consent offend many. The fact that he has used the clout provided by the majority of shares he controls to work his way back onto the Board of the Directors and the Executive Chair position, claiming his presence is integral to the ‘best interest’ of those shareholders (primarily McMahon himself) and that without his involvement in shaping the trajectory of the company, those shareholders (McMahon again) would refuse to approve any significant direction, fall in my view, squarely in the “wrong” category even if they seem legal from a distant onlooker’s point of view.

I should note that since I started writing this piece, Vince’s daughter and WWE co-CEO and Chair Stephanie McMahon, has resigned her positions and left the company. Her fellow CEO Nick Khan now holds that role himself. Head of Creative Paul Levesque — Triple H and Stephanie’s husband — is still on board for now but depending on where this roller coaster ends up it is difficult to see him staying on for long. The optics of an 80-year-old Donald Trump-supporting alleged predator returning to a New Media company while his daughter, newly minted to the CEO role after her own brief sabbatical, are problematic. Within WWE Stephanie was comparatively progressive; she and Triple H prioritized representation, giving better platforms to women and racialized performers on WWE programming. Not perfect and a cynic would suggest that Stephanie’s action is more performative than sincere, but it bears mention in light of where this column is heading.

To be clear, I don’t provide legal advice of any sort in this column (or elsewhere) and my opinions are my own. I’m also not a businessman, although I hope one day to be like Jay-Z “A business, Man”.

As prodigal CEO returns go, this isn’t a new story. Jack Dorsey left and returned to Twitter pre-Musk. Mark Pincus left Zynga in 2013 and returned within two years. AG Lafley came back after a three year absence from Procter & Gamble, using similar language; coming back at an “important time… to further improve results, implement the current productivity plan and facilitate an ongoing succession process.” Starbucks CEO Howard Schultz led a significant restructuring effort after eight years away. Most famously, Steve Jobs was forced out of Apple in 1985 and returned in 1997 when the fruit company purchased his NeXT startup. That went well. Most recently, Bob Iger has returned to the CEO position at Disney, replacing Bob Chapek who held the role for two years.

Of course, the Return of the King is rarely as freighted with public ill-will and potential lawsuits as it is in this case. News of McMahon’s return was greeted with the announcement of a prospective shareholder lawsuit, and with good reason. These days executives who use their positions to take advantage of women are more likely to be indicted than reinstated to their Boards. As I mentioned when WWE’s misconduct scandals first broke, CNN President Jeff Zucker resigned over one affair with a much more senior colleague.

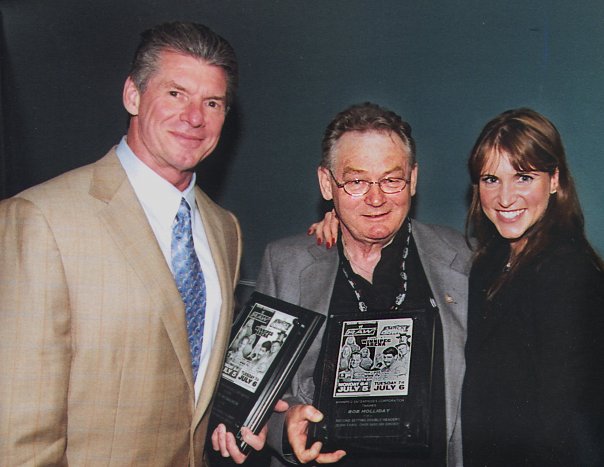

Vince and Stephanie McMahon with Bob Holliday in July 2004.

At first blush, it seems that Vince has overtaken the WWE’s Board of Directors to begin a potential sale process. Financial services giant J.P. Morgan has been hired in an advisory capacity, and the prospective sale of WWE is being timed to coincide with television rights renewal negotiations. The sale of WWE has been a hot topic since April 2022, with rumors heating up in July as word of McMahon’s misconduct spread. In the wake of Vince’s return and Stephanie’s departure the internet was quick to suggest that a sale to a Saudi Arabian government agency had already happened. It now seems like this is just an example of internet wrestling fans’ imaginations running amok, but for reasons I will set out below I don’t think it’s a far-fetched conclusion, or one that bodes well for the long-term health of WWE.

But first, let’s look at some of the dynamics associated with a potential sale. Valuing a business can be tricky under the best circumstances. For a billion dollar nominally public company, things are more complex but the basic idea in valuation is to arrive at what those in the know call the ‘fair market value’ of the business. The rules may be different in the US but here in Canada, fair market value is the highest price, expressed in dollars, that the business would bring in an open and unrestricted market, between a willing buyer and a willing seller, both of whom are knowledgeable, informed, prudent, and act independently of each other.

Different basic approaches can be used, including the following:

- Value of Assets: The sum of the value of everything the business owns, including all equipment and inventory, less any debts or liabilities. This is the basic information that will be captured on a business’ balance sheet, but in a complex entity like WWE which relies heavily on licensing and intellectual property and good will, it’s fair to say that the actual business is worth a lot more.

- Revenue: The amount of annual sales generated by the business, compared to a typical business with a certain level of sales.

- Earnings Multiples: More typically used to calculate a company’s worth, this approach considers a multiple of the company’s earnings or price to earnings ratio. Earnings for the next few years may be estimated and the ratio applied to give a longer-term estimate of value, so a prospective buyer has a clearer sense of how the business will perform over time.

- Discounted Cash Flow Analysis: OK, now we’re getting beyond my amateur wrestling columnist pay scale, but in a nutshell you apply a formula that begins with the annual cash flow and projects it into the future, then discounts the value of the cash flow to the present using a “net present value” calculation. I could Google this but I’m not gonna.

- Extra-Financial Analysis: Here’s where valuation becomes complicated, especially when it comes to publicly facing companies like WWE. Value means more than physical assets, otherwise WWE is the sum of its production trucks and equipment and video library — which is not considerable, but a bunch of tapes lack value if they’re not used in a compelling way. Factors like geographical location, strategic value and potential business synergies can help increase a business’ value.

Under any sale scenario it would seem that WWE’s most valuable asset is its bank of intellectual property. WWE has always aggressively protected its own IP and sought to acquire others’, building a library so vast that it spun away from conventional television — first programming and third party pay-per-views and into towards its own Network, which currently airs on NBC’s Peacock streaming service. The fact that WWE owns so much of its intellectual property (including wrestlers’ ring names and theme music) gives it a clear path to stream content exclusively. WWE sells its licenses; it doesn’t buy them. This also gives it a pipeline for merchandise, music compilations, TV and film projects, and whatever attractions it may decide to brand. Think about WWE Niagara Falls. Or WWE New York. Or the still imaginary Hall of Fame.

Vince is spinning his return as best he can but as usual facts get in the way. He issued a statement as follows: “My return will allow WWE, as well as any transaction counterparties, to engage in these processes knowing they will have the support of the controlling shareholder…” McMahon pledged not to tamper with current leadership but his return has seen about half of WWE’s Board of Directors replaced with those who align with his vision, and Stephanie’s departure. It is rumored that he wants to retake creative control as part of any deal, although he may face considerable internal and external pressure to remain hands-off. His track record when it comes to promises suggests this one ranks near Bad News Brown’s WWF title run, Bret Hart’s 10-year contract to keep him from joining WCW, the sale of Stampede Wrestling in the 1980s or retaining existing Georgia Championship Wrestling content on TBS following Black Saturday. If a sale does happen imminently, it remains to be seen where Vince would fit in. Prospective investors would do well to trust but verify.

Despite the weirdness of WWE’s chief (and apparently super-activist) shareholder cheerleading a potential sale, Vince may have a particular understanding of WWE’s value as a brand and the intellectual property that underpins it. Vince built Titan Towers on the base of his father’s New York office, putting his dad’s co-conspirators out of business. WWE bought out dead promotions like World Class Championship Wrestling, Stampede Wrestling and the American Wrestling Association even though their chief (in some cases, sole) assets were their libraries. He has used these libraries as the basis for WWE Network Programming, DVD releases and occasional ironic t shirts. WWE tried to wring further life from WCW, which it acquired for $4.2M (it bought the trademarks and logo for $2.5M and the tape library for $1.7M). WWE bought ECW’s assets from HHG Corporation following that promotion’s bankruptcy, where it had listed assets worth almost $1.4M vs. liabilities totaling almost $8.9M. ECW had an arguably more successful rebirth but the biggest value from each sale would be the hours upon hours of matches featuring future WWE stars.

Outside of WWE, Ring of Honor was purchased by AEW owner Tony Khan; after talent was let go it was basically intellectual property rights, a few trucks, rings and banners. WCW became a force in the late 1990s following Ted Turner’s purchase of Jim Crockett Promotions, which was itself on the verge of being put out of business by the then-WWF’s national expansion and raid of syndication and cable providers. On a smaller scale, music producer Rick Rubin was an original investor in Jim Cornette’s Smokey Mountain Wrestling. He was a huge wrestling fan but bailed as it became clear this wasn’t going to make him money. Let loose from Crockett, the NWA has changed hands a few times in recent years including Billy Corgan’s recent purchase. In each case the sale involved a distressed asset. The lesson that I take from this is that successful wrestling promotions are rarely sold. You might have to go back to the territory days when healthy promotions came up for sale — but a lack of transparency and ‘old boys network’ meant those transactions often involved talent directly, giving the ‘boys’ a piece of the office. I tend to think a lot of those promotions failed after being sold, too. Wrestling seems to be based heavily on cults of personality. Locals understand their markets and how to manage the team that is needed to make a show work. There may also be a fair amount of grift and puffery involved. While I don’t think Corporate America is naïve, I think most executives would balk at the carny nature of wrestling and close up shop once they realize how things work.

Given how potential suitors like Fox, which paid more than $1B to air SmackDown, or Comcast, which is the parent company of NBC Universal and Peacock — the WWE Network’s current streaming home — are already in business with WWE, one can see the appeal of a synergistic argument. Endeavor, which owns pro wrestling’s “real” cousin the Ultimate Fighting Championship and Amazon, which is relentlessly thirsty for content and previously broadcast the late Howard Brody’s Ring Warriors lone season have also been floated, along with the likes of Disney, Apple, Paramount and Netflix.

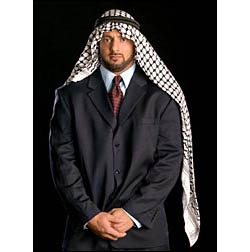

Muhammad Hassan

Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund, which has already entered into an extremely lucrative arrangement to put on mediocre WWE shows overseas, has also been mentioned. In fact, in the wake of McMahon’s return they were reported as having already bought WWE — a development that left many fans angry and threatening to boycott the company over human rights issues. Past reluctance to feature female performers on Saudi Arabian shows (and lately, to include them but in culturally-appropriate costumes) and other matters of conscience for WWE performers like Sami Zayn, Kevin Owens, John Cena and Daniel Bryan have raised concerns about how WWE’s product would be affected if the Public Investment Fund were successful. We know from WCW’s sale to larger corporate interests means input into creative decisions. At minimum, it is difficult to reconcile foreign ownership with the jingoistic nature of WWE broadcasts. How does WWE run its Tribute to the Troops at US military bases when they work for a government with a sometimes contentious relationship with the US? Could WWE continue to present itself as patriotic, as it has going back to Hulk Hogan beating the Iron Sheik or Sgt. Slaughter as a featured babyface performer? WWE and pro wrestling in general have used Middle Eastern stereotypes to generate heat forever. Even following 9/11 Muhammad Hassan was portrayed as a villain — and was ultimately removed from SmackDown after complaints from media outlets and SmackDown’s then-broadcaster, the UPN network … which, following its own shutdown is now split between potential WWE suitors Warner Brothers Discovery and Paramount Global. When the decision was made to turn Mustafa Ali heel (Ali is of Pakistani descent, but this seems less important to wrestling fans) he leaned into grievances about his treatment by WWE, its fans and society as a Muslim.

That said, in wrestling money talks and what the Public Investment Fund may lack in direct wrestling knowledge (this is the same outfit that expressed an interest in seeing the long deceased Yokozuna and Ultimate Warrior), they make up for in resources with over $620B in assets. The Fund owns PGA competitor LIV Golf and the Premier League’s Newcastle United franchise.

Warner Brothers Discovery is already in the rasslin’ business. In fact, its predecessor Time Warner was probably the first major corporation to enter the fray, when it purchased WCW as part of Turner’s portfolio of assets in October 1996. WCW had been founded by Ted Turner in 1988 after Turner Broadcasting System purchased the assets of Jim Crockett Promotions — one of the last bastions of the old NWA following the WWF’s national expansion. Legend had it that Turner had a soft spot for wrestling, which provided cheap programming for his fledging media empire. Turner also had a hard edge when it came to Vince McMahon and his aggressive negotiations over broadcasting rights. After a honeymoon period during the Monday Night Wars, by 1999 WCW’s TV ratings sank. Revenue dried up for reasons best chronicled by R.D. Reynolds and Bryan Alvarez in their book The Death of WCW. The merger of Time Warner with America Online drew more attention to wrestling’s lack of profitability and inconsistency with a higher-end brand. The last episode of WCW’s flagship show, Nitro, aired on March 26, 2001, with special guests and new owners — the McMahons. Still, decades after killing WCW and selling it to WWE, Warner Brothers Discovery holds the TV rights for AEW, which airs on Turner legacy superstations TBS and TNT.

While there are many key differences between the financial and creative positions of both companies, it’s worth noting that WCW in 2000 also attracted its share of speculation regarding potential purchasers. Among them, former WCW head Eric Bischoff had joined with Fusient Media Ventures (a now-defunct venture capital firm) to buy and keep the company alive. This fell through in part when AOL Time Warner refused to keep airing WCW programming since pro wrestling was out of line with the bigger company’s public image.

Notwithstanding the wealth of lowbrow programming put out by all of the suitors mentioned above, it’s difficult to put an accurate value on a media property like WWE which by its nature skirts the boundaries of good taste and is subject to huge shifts in popularity over time. Many commentators have pointed out how ill-suited pro wrestling is to a more corporate environment. Wrestling insiders typically blame clueless network executives for silly creative decisions, but as the smaller fish in the bigger pond WCW actively contributed to its own demise. For example, in 1992 Bill Watts was named Executive Vice President of WCW. Watts had a strong reputation in wrestling circles following the success of his Mid-South/UWF promotion. He failed in a broader corporate environment, clashing with management, exhibiting boorish behavior unbecoming an executive (he was notorious for finding ‘creative’ spots to relieve himself) and giving an offensively racist interview which was brought to baseball legend and fellow Turner (Atlanta Braves) executive Hank Aaron’s attention, resulting in Watts resigning. In 1994, on-air personality Missy Hyatt filed a lawsuit against WCW alleging, among other things, sexual harassment. Hyatt claimed that Watts’ successor, Ole Anderson, made demeaning remarks and propositioned her. She also alleges that photos of her suffering a wardrobe malfunction were circulated around WCW offices. In 2000, manager Sonny Onoo filed a class action lawsuit against the company alleging racial discrimination. The case was later settled out of court. What was accepted in a privately-owned enterprise shocked the conscience of the media conglomerate. And it should be a cautionary tale when it comes to WWE’s next step. It is unlikely that a corporate parent would abide another Plane Ride from Hell.

Missy Hyatt

Prospective buyers may look at the success of the WWE Network, the mainstream success of Batista, John Cena and The Rock (more on him, later), or a share price that jumped on the news that Vince would be returning to the company he inherited. If they look a bit deeper, they may see dodgy storylines like the aforementioned Muhammad Hassan or Katie Vick or Roddy Piper in allegedly well-intentioned blackface, all of which WWE has worked hard to scrub from its own archives. They may see the scandal that forced Vince McMahon from his own company, ever so briefly, and the fact that his return prompted the immediate resignation of two other board members — including the one who called for and led the internal investigation into his actions. They may read WWE’s Board of Director’s letter sent urging Vince not to rejoin the executive team, citing ongoing concerns about the effect that his conduct may have on the company’s value, the allegations that he used company funds to bankroll his love life for decades and their fear that further scandals may be uncovered. They may see further instances of misconduct going back to the 1980s involving Vince and other senior officials — the ring boy and steroid scandals, sexual assault allegations made by former referees and briefcases brought to police stations, much of which lay outside broad public knowledge since the then-WWF was a private entity. As I write this, WWE is worth approximately $6.5B. To a major entertainment company concerned about the potential for reputational damage, a spell of bad ratings or a Bill Watts-style racial tirade in front of the wrong microphone shuts the whole enterprise down. To Disney or Amazon or the Saudi Arabian Government, $6.5B is a rounding error.

Putting WWE up for sale with Vince on board feels like a significant gamble. I half-suspect that his return may be fueled by the fact that his misconduct and the use of company funds to support it is not the only instance of creative accounting. Current share prices notwithstanding, his involvement in any kind of corporate heavy lifting seems like it would be a disincentive to prospective purchasers (but, as mentioned, I’m no businessman). I keep thinking of the Wizard of Oz trying to misdirect attention from the ‘man behind the curtain.’ Despite Vince’s age (noted wrestling and cultural critic Evan Ginzburg might call me out here, since he views ageism as the last acceptable prejudice) I think there’s a different play here. I don’t know whether Vince wants to retake creative control. Even if he thinks he does not, his controlling nature is apparent to anyone who reads the dirt sheets; he may not be able to stop himself from meddling even if he wanted to.

I see two alternate outcomes as more likely than a sale to a third-party public company. Interestingly, both were directly contemplated in McMahon’s initial press release, although neither has attracted the same level of attention as the prospect that WWE goes full Big Business.

My first guess is that this is an attempt to take the company back private — in fact, this is what is proposed as part of a sale to the Public Investment Fund. To go private, a company undertakes a transaction which turns a publicly owned company (one that is owned by shareholders, who can buy or sell shares on an open market) into a private one (the company is effectively sold to one or a few shareholders and taken off the public market). Private companies have their advantages: being a public company involves expensive and time-consuming interactions with regulators, extensive financial reporting, corporate governance and public disclosures. Going private alleviates many of these pressures; it frees up capital and provides flexibility since there are fewer interests to take into account. WWE wouldn’t be the first company to go private. Companies like WestJet and HJ Heinz have also gone private as a strategic decision when the stock market tanks. Sometimes companies will go private to facilitate a reorganization, then put themselves back in the public realm once the deed is done.

For a company which has experienced scandal, one benefit of going private is that WWE would stop being a ‘reporting issuer’ and would fall outside the scope of a host of public reporting laws. Transparency regarding finances and internal investigations would be limited, which would insulate WWE from the glare of the US Securities and Exchange Commission’s regulations and effective public scrutiny. It also precludes the possibility of shareholder lawsuits, which have been threatened since McMahon was caught out. Going private would tempt Vince and his cronies go back to business as usual in all its debauchery, with fewer public safeguards. Again, ‘legal’ if not ‘right.’

Alternatively, WWE’s play could be for a consortium led by an insider like Nick Khan with The Rock as the new public face of the company to take over.

Nick Khan

I like the this option because I get to use the term “Khan-spiracy” again, and because it makes sense.

Vince and The Rock have done business over the XFL. The Rock has kept a relationship with WWE over the years. He and Khan are childhood friends and Khan’s sister is the showrunner on Young Rock. To me it feels like a great long con… and it means that there would be people in visible positions who know the wrestling business. Of course, this seemed to be the way WCW was headed with Bischoff and Fusient back in the day, and I’ve covered why that didn’t work out so well. The Rock may be motivated to return to an entertainment field where he is unchallenged. A recent attempt at a power play in support of his Black Adam franchise has left him outside the DC Universe looking in. With Vince McMahon as the heel holding WWE captive, I’d expect the WWE Universe would greet The Rock as a liberator.

Of course, all of this is pure idle speculation. And for someone who views a little knowledge as a dangerous, but very fun thing, that’s the best kind.

TOP PHOTO: Vince McMahon making his in-ring debut against Stone Cold Steve Austin. WWE photo

RELATED LINKS