All Elite Wrestling recently celebrated its third anniversary, and with it, a move to a larger television platform from TNT to TBS.

This is great news for fans who enjoy the action that AEW provides — -the more grown up storylines, the heartfelt promos and interviews, and the emphasis on longer and more innovative matches.

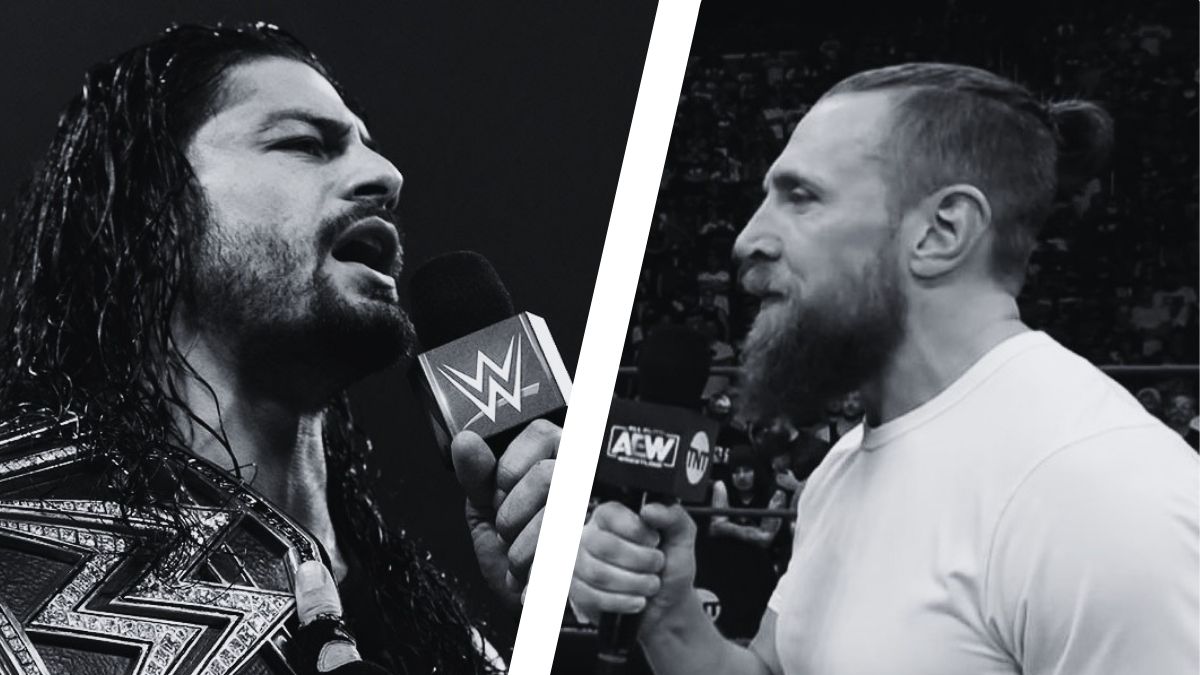

Fans also note that one of AEW’s great strengths has been repurposing talent who seemed to languish in WWE. Wrestlers like Malakai Black, Andrade and Cody Rhodes have shown sides of themselves we never got to see elsewhere, and established acts like CM Punk and Bryan Danielson are getting the final acts their careers deserve, putting on the kinds of performances denied to fans by WWE’s rigid approach to booking and time constraints, before suitably large audiences.

And those audiences are large and growing; AEW has drawn impressive TV ratings and spectators for house shows despite the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. They’ve expanded the content across platforms and don’t seem to be slowing down.

So it’s no surprise that fans — and apparently some inside AEW — are calling for a head to head ‘war’ between AEW and WWE. AEW already beat WWE’s developmental-focused brand, NXT, in head-to-head competition, and some are begging AEW to challenge WWE’s main TV shows, and “put them out of business.” In my view, that’s the worst thing that could happen to pro wrestling and for fans.

I get why some fans may want to see WWE fail; it’s been the only game in town for almost 20 years, and the idea that AEW, which has consciously tied itself to the former National Wrestling Alliance (NWA)/World Championship Wrestling (WCW) legacy must appeal to fans who feel lost without the latter’s often more grown up presentation. AEW has successfully combined newer aspects of pro wrestling athleticism with an older, Southern US approach to booking feuds.

AEW emphasizes tag team wrestling, larger stables and blood in its feuds; characters are more grounded and legends familiar to NWA/WCW fans like Sting and Tully Blanchard and Jake Roberts connect adult fans to the wrestling they remember. It’s still occasionally goofy, but so far we are willing to overlook that for the quality matches we get to see weekly.

This contrasts with WWE storylines, which seem stale and focused on the same few characters, and WWE’s failure to advance new, diverse talents like Malakai (Alastair) Black, Bray Wyatt, Karrion Kross or Keith Lee, who have succeeded elsewhere (including NXT) only to be repackaged, blamed for failing to get over with fans, and released. Some viewers see WWE getting its comeuppance as justified, if only for its painful labor practices, including waves of releases during the pandemic.

Further, as wrestling fans we are conditioned to see things as stark contests for survival; battles of good vs. evil where only the strong survive. History confirms this; WWE succeeded by swallowing territories across the US and Canada, including its last two main competitors — Paul Heyman’s ECW and Eric Bischoff’s WCW — and both men eventually came to work for WWE.

But a funny thing happened; with WWE as the only game in town, storylines and rosters started to stagnate. Talent stayed locked into WWE since it was the only game in town, and without competition there was little incentive to innovate. Where competitors arose, WWE would still conduct periodic talent raids, keeping them small. Before AEW, TNA seemed primed to challenge WWE with a younger, faster roster and more risqué storylines… then they decided to challenge WWE programming head-on and lost tremendously; the company has never recovered and actively seeks to collaborate with others, including AEW for survival. TNA (now Impact Wrestling) has also granted its talent much broader control over their intellectual property as an incentive to stick around, however long.

While the North American wrestling scene seems to be thriving, it is also undergoing a period of consolidation. AEW’s earliest days dovetailed with the end of Lucha Underground, which had provided a platform for talent including Ricochet, Brian Cage and John Morrison. Lucha Underground only ran four years but offered North American wrestling fans a decidedly different brand of wrestling and heralded the trend towards ‘cinematic’ matches where storylines and theatrics outstrip in-ring action.

Viewers who point to AEW’s success must remember that it was born in large measure by signing talent from Ring of Honor and Impact Wrestling. It’s hard to argue that even without the pandemic, the exodus of talent from ROH, which necessarily kept a smaller roster, hurt business badly. ROH did the right thing by its wrestlers through the beginning of COVID, paying their contracts out while WWE has released waves of talent in an environment that could not find venues to perform. Ultimately that decision was not sustainable. ROH effectively paused operations at the end of 2021, and those wrestlers whose salaries had been paid were released to a stronger buyer’s market. While ROH may yet come back, it seems like they will do so without a full-time roster, meaning fewer opportunities for wrestlers to work under contract. ROH has been a breeding ground for AEW and WWE talent for the past decade; many of both promotions’ most successful acts honed their skills there. Many WWE backstage personnel have extensive TNA, NWA and ROH stints on their resumes rather than WWE.

From an in-ring standpoint, the lack of viable competition means WWE has largely failed to create its own new stars. TNA and ROH talent pervade their main roster and attempts to recreate the experience of learning how to work via NXT have not proven successful. Better to treat NXT as a finishing school for established acts who need to learn the peculiarities of WWE, than a way to teach random athletes from scratch.

The fact is, WWE and AEW need each other and as many other players as they can afford to get in the game. From a creative point of view, the more entrants into wrestling, the more places for talent to learn, get better and work in front of spectators. The more backstage opportunities for people to learn this specific art of storytelling. Cheering for WWE to fail means putting hundreds and hundreds of people out of work, instead of gossiping who can be absorbed by competitors. It means that talent who run their course in one promotion lose the chance to reinvent themselves elsewhere, and those who get cut early in their careers lose the opportunity to rebuild themselves for future main event runs. It means a huge hole in wrestling programming, and the deaths of WCW and ECW show that with fewer options in the wrestling market becomes a lot less entertaining.

RELATED LINK

TOP PHOTO: Roman Reigns and Bryan Danielson. WWE and AEW photos.