The initial story told in my first wrestling book, Bluegrass Brawlers, is one that has captivated me ever since I first read it. I’ve never shared the full story online before now. It’s the story of a young lady who came to Louisville in 1880 with the circus and won the whole town over in an intergender wrestling match.

You read that right. An intergender wrestling match took place in Louisville, Kentucky way back in 1880.

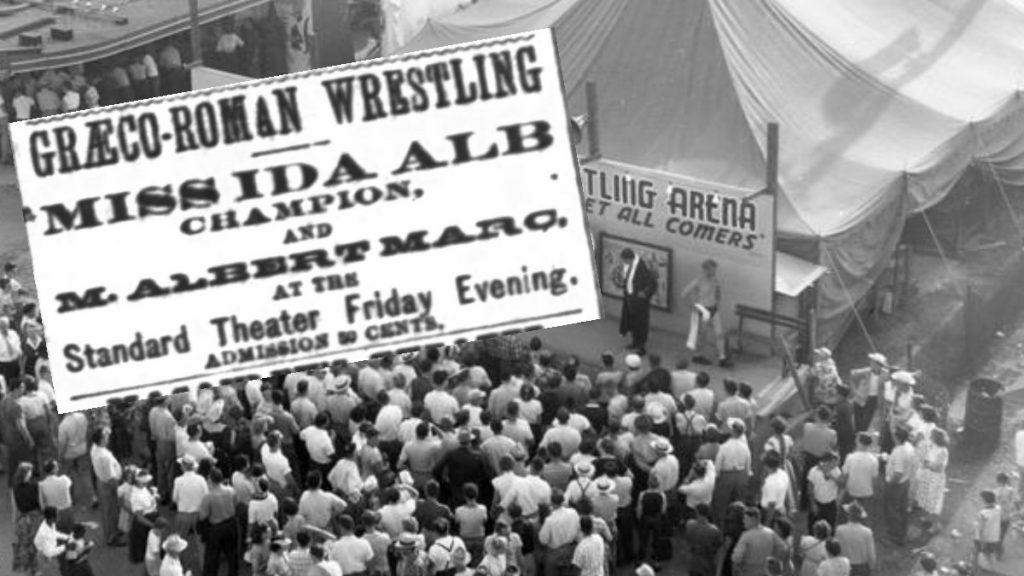

The circus in question was not that of the better known P.T. Barnum but one of Barnum’s rivals, Adam Forepaugh. Like Barnum, Forepaugh was a wrestling enthusiast and had an “Athletic Show” in the midway where fans could see wrestling matches. One of his top attractions was a 5-foot-3, 150-pound pixie named Ida Alb. Alb captured the attention of Louisvillians with her exhibition matches against fellow circus performer (and sister) Mademoiselle Marcia.

Alb’s visit would have come and gone without any major press coverage had she not taken umbrage with allegations that she and her compatriots were hippodroming: an antiquated term that referred to staged athletic contests with a predetermined finish. It’s not made clear who was making such allegations against the circus performers, but they provided Alb with a chance to gain some press coverage for the circus while defending her livelihood.

The June 1, 1880, edition of The Courier-Journal states that Alb issued an open challenge to any Louisvillian in her weight class to step in the ring with her. A day later, her challenge was answered in the paper by Albert Marc, a Frenchman and a highly skilled athlete in his own right. An agreement was signed at the New Southern Hotel on June 2. Both wrestlers would receive $50 for the match, and the winner would be declared the Kentucky state champion.

The Courier Journal, June 4, 1880.

The match took place in front of a packed house at the Standard Theater. After an unexplained delay, a man appeared in the audience at 20 minutes until nine to read the rules for the match:

- No holds below the waist allowed.

- No scratching or kicking.

- Contestants must wear soft-soled shoes or socks.

- Finger nails had to be cut close.

- When a contestant touched both shoulders to the mat, they would lose one fall.

- Best three out of five wins.

- One referee and two judges would be chosen from the audience.

Albert Marc was first to make his entrance, played to the ring by a band of African-American musicians. Standing at 5-foot-3 with “black hair, black, sparkling eyes, and a good humored face,” he was dressed in loose fitting white tights, a red shirt, and blue trunks.

With a flourish of music from the orchestra pit, Miss Ida Alb appeared, skipping lightly and pausing to blow a kiss to musicians. The “luscious damsel with a pert smile,” was described by the poetic sports writer as far less dressed than her opponent. She wore red tights “which fitted like she had been poured into them with a ladle until the point of running over was reached.” She wore a blue leotard over top of the trunks tight enough that “the human form divine was outlined as perfectly as the most fastidious anatomist could have desired.” Ida was of equal height to her opponent but had a 17 pound weight advantage, and her tight fitting costume revealed that the difference in weight was all muscle.

The competitors stood before their audience as the judges and referee were selected. Arthur Suarez, described by The Courier-Journal as being from France, was chosen to be Marc’s judge. The rotund Suarez danced about outside the ring throughout the match, voicing his admiration for Alb and declaring he would challenge her himself given the chance. Alb’s judge was a wrestler named H. Schulen. Sam Self acted as referee, and The Courier-Journal notes he performed his duties with “grace and occasional relapses of deep emotion.”

Alb appeared to be nervous as the match began, while Marc was the picture of cool composure. They traded holds and flips with one another until Marc managed to take Alb down for what he thought should be the first fall. Alb protested her shoulders did not hit the mat, and the referee disallowed the fall. Alb went in for her best hold, but Marc slipped out and managed to get her shoulders pinned to the mat, scoring the first fall in 13 minutes.

Marc was energized as the match resumed, while Alb looked tired. Marc caught her in a headlock, but Alb escaped by tossing him overhead. She tried to roll his shoulders onto the mat, but he escaped and the match continued. Alb repeated the maneuver and this time got both shoulders to touch as he rolled across the mat. Her judge demanded the referee score a pin fall in her favor, and Sam Self gave Alb the fall.

The audience was really into the match, cheering the competitors on as they began round three. Alb came out with a vengeance, looking to continue her momentum. She tossed Marc a few times and tried to claim her second fall, but Marc managed to wriggle free before she could pin him. When Marc rolled up on his side to avoid being pinned, Alb grabbed him around the waist, flipped him with a somersault, and landed face down on top of his chest, scoring her second pin in six minutes.

With his back against the wall, Marc came out with renewed vigor in the fourth round. He caught Alb in a headlock and tried to roll her on her back, but Alb kept her shoulders off the mat. With a loud laugh, Alb attacked Marc, but Marc was ready for her and flipped his opponent, nearly scoring his second pin fall. Marc attempted the maneuver twice more to no avail, but he finally evened the score when he caught Alb in a back-neck hold and turned her over, pinning her squarely to the mat. Reluctantly, the referee scored the fall for Marc at fifteen minutes. It would all come down to one final fall.

By now the audience was completely in Alb’s corner. The referee was too, but he resolved himself to call the final pin fairly. Alb came at Marc at full speed. Marc out-maneuvered her and tried unsuccessfully to go for the pin. In the tumult Marc grabbed her legs above the knee, an illegal move, per the terms of the match, and Schulen demanded the referee disqualify the challenger. Alb refused to win that way, stating that she wanted the match to end the right way, with a pin.

The competitors battled on the mat, each trying to use their weight to seize the advantage and win the final fall. Marc grabbed Alb by the shoulders and threw her, rolling over on top of her with his full strength, but he failed to score a pin. They locked up again, and this time, Alb wrapped her arms through his and gave him the bridge throw, scoring the final fall.

The audience erupted with cheers. Marc and Alb shook hands and bowed to the audience. Alb then announced that she would challenge Marc to a second match on June 17 following an engagement in St. Louis. Marc accepted on the spot. Alb gave Sam Self a kiss, and the evening was over.

There’s no further mention of Ida Alb in The Courier-Journal archives to tell who won the rematch or whether one even took place, but it would not be Ida’s last match with a man, or her last brush with mainstream fame. According to The Cincinnati Enquirer, Ida agreed to another man vs. woman match in St. Louis versus a man named Charles A. Standbrook. Standbrook took the first fall against the much smaller woman, but Alb rallied to take the second and third falls and claim victory. Alb and Standbrook would face off again later that summer in Montana

It’s not too much of a stretch to read between the flourished lines of the newspapers to see that all of these matches were most likely staged. The At Shows were staged exhibitions with fixed finishes, and it was not uncommon for promoters to plant ringers in the crowd posing as locals to take on the wrestlers. What’s more, Lucien Marc is listed on a few wrestling cards alongside Alb and Marcia in other towns.

Nevertheless, Ida Alb left an impression on the Louisville audience not easily forgotten. The match garnered mention in a few other publications as well including The Pall Mall Gazette in London, England. Ida Alb made at least one return visit to Louisville when she and Mademoiselle Marcia arrived in late January of 1881 for an engagement at the Buckingham Theater as part of an exhibition of novelty acts.

The Courier Journal, April 14, 1882.

Tragically, on July 6 of that same year Ida was found dead in Milwaukee from an opium overdose. Numerous papers across the country carried the story in which she was identified her as a member of Forepaugh’s circus. “It is supposed from things found in her trunk that she is a Cleveland girl,” the article’s final sentence begins, “but her real name could not be discovered.”

A more in-depth obituary appeared in the Cincinnati Inquirer a week after her death. Alb’s real name is never revealed, but the article confirms that letters found in her trunk indicated she was from Cleveland and had a sister in Pittsburgh. The Inquirer also notes that Alb had been recently been discharged from Forepaugh’s Circus, prior to which she had been a song and dance performer. The Inquirer also makes note that she had been part of a wrestling act prior to joining the musical act.

I’ve made numerous inquiries with circus historians and museums to try and learn more about Alb and Marcia. I’ve come up empty so far, but this is one story I can’t let go of. A lot of time has passed since Ida Alb’s tragic end, but I keep hoping another clue might surface that will shed more light on this early wrestling pioneer.

Ida Alb would not be the last wrestler to die tragically at a young age, but she made her mark on the world of professional wrestling and the city of Louisville. She blazed a trail for male and female wrestlers, creating an appetite for the drama and the action of professional wrestling.

The story of Ida Alb was first printed in the book Bluegrass Brawlers: The Story of Professional Wrestling in Louisville. A story inspired by Alb also appears in the book Grappling by Gaslight, a collection of short stories inspired true life tales of wrestling in the late 19th century. Both books are available on Amazon, and signed copies can be purchased at www.eatsleepwrestle.com.

TOP PHOTO: Jimmy Demetral’s AT show tent, Courtesy Scott Teal, Crowbar Press

RELATED LINKS