Jim Crockett Jr., the promoter who took his father’s Mid Atlantic Wrestling regional promotion and made it into a national entity as the National Wrestling Alliance / World Championship Wrestling, has died. He was 76.

He had been in ill health for the last little while.

James Allen Crockett Jr., was born August 10, 1944 in Charlotte, North Carolina, to Jim and Elizabeth Crockett. He went to Myers Park High School. He was one of four children, including David, Jackie and Frances.

When Jim Crockett Sr., died on April 1, 1973, Jim Jr. was one of three people who took over Crockett Promotions, Inc. — known to wrestling fans as the Mid Atlantic territory since the 1970s — which was run out of a two-room office on Morehead Street in Charlotte. He had been around the promotion a bit while his dad ran it, the talent referring to them as “Big Daddy” and Little Jim, but had little say in day to day operations.

Prior to wrestling, Crockett Jr. had been involved with North Carolina’s Republican party, and had even attempted to win a seat in the state senate. He finished last in a field of five.

The others to take over the wrestling operations were Jim’s brother, David, and John Ringley, who was Crockett Sr.’s then-son-in-law. Ringley had been groomed to run the wrestling end of the family business, but didn’t stay involved very long, because he was caught cheating on his wife Frances Crockett. Elizabeth Crockett and Frances were definitely involved too. Jim later installed his sister, Frances, as the general manager of the Charlotte O’s Class AA baseball team.

“It just isn’t like a normal business,” said Crockett Jr. about pro wrestling in January 1975 in the Charlotte News, when he was 29. “I enjoy it. It’s a whole different lifestyle that I’m not sure I could give up at this point.”

The tale of the territory is a remarkable one, full of amazing heights, the national spotlight, fights with Vince McMahon and the World Wrestling Federation, lawsuits, and, ultimately, a sale to Ted Turner and his Turner Broadcasting Corporation in 1988.

George Scott was hired as the new booker in the territory. He told this site that it was Ringley that hired him, and that “Jim Crockett Jr. knew nothing about wrestling.”

Whatever Crockett Jr. did and didn’t know about wrestling didn’t especially matter, as he had a business mind. Scott helped the promotion expand, as Crockett bought into the Tunney’s Toronto promotion, expanding into Buffalo, with Crockett owning a third, Scott a third, and the Tunneys owning the rest. Later in the 1980s, Crockett bought the Florida promotion and Kansas City.

An Associated Press story from early in Crockett Jr.’s ownership noted that his company produced wrestling programs seen on 24 stations in North and South Carolina, Georgia, Virginia, Texas and West Virginia. “According to the latest ratings, we have 1.06 million adults watching the program each Saturday,” Crockett said in the article. “Our program delivered more adults than ABC Wide World of Sports, CBC Sports Spectacular or NBC sports in the same market.”

In the article, Crockett declined to reveal just how much his corporation was worth; he did say that business had grown “a steady five to 10 percent every year for the last four or five,” and could show a 25 percent increase by the end of this fiscal year.

But Crockett didn’t do it on his own. His booker, Scott, took a territory that had relied on tag teams and built it around stars such as Blackjack Mulligan, Johnny Valentine, Wahoo McDaniel, Masked Superstar (Bill Eadie), Paul Jones, and lucked into rising stars like Ric Flair, Roddy Piper and Ricky Steamboat.

What was the growth like? Scott recalled that payroll went from $20,000-$25,000 a week when he started to $100,000-$200,000 a week when he quit in 1981. “We did ungodly numbers in the Carolinas,” recalled Scott in a 2001 interview.

In a Raleigh newspaper in 1979, Crockett said, “TV is the maker and killer of us all.” The TV arm of Crockett Promotions was a subsidiary, National Electronic Mobile Operations. It rented out its trucks for other events, such as basketball games or concerts. It was forethinking. “We feel with the expansion of cable there is going to be a great demand for production facilities,” said Crockett in a 1983 story.

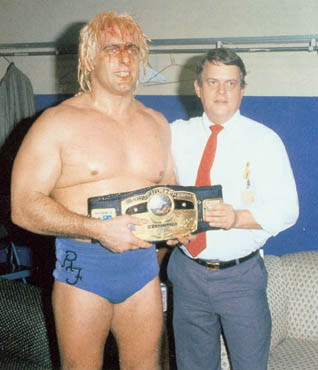

NWA World champion Ric Flair and Jim Crockett Jr.

“King Kong” Angelo Mosca was one of the talents that Scott brought down to the Carolinas. “Very clever guy. … He knew how to put talent together — or as they say in the business, create narratives,” Mosca said of Scott. “George was good that way. He ran a very tight ship. Jimmy Crockett was a pretty good payoff guy.”

The split between Crockett and Scott was not amicable, and ended up in the courts — Crockett Jr. sued Scott, but then dropped the case. (Later, Scott sued Jack Tunney for the money he never got when Tunney sold out to the expanding WWF.)

Another lawsuit happened when Johnny Powers (Dennis Waters) tried to promote International Wrestling Association shows in the Carolinas. Powers had respect for the Crockett family and what they meant. “Wrestling was the premier sports franchise, with the premier audience base and that had been built up by the Crocketts, who did a superb job with that,” he said. Ultimately, Powers was forced out of the Carolinas. The Crocketts used their many connections to keep venues closed to outsiders. Besides running a minor-league baseball team in Charlotte, to keep Powers out of Winston-Salem, NC, the Crocketts invested in a minor-league hockey team to gain control of the arena.

As the Mid Atlantic territory grew, it became Jim Crockett Promotions (JCP), but more familiarly to fans as the National Wrestling Alliance (NWA) — since it had the biggest platform on WTBS — and World Championship Wrestling.

Crockett became president of the NWA in 1980 and served three terms. His promotion became the NWA as other territories were steamrollered by the WWF.

The story of how Crockett ended up on TBS is one of legend. Briefly, Georgia Championship Wrestling had the timeslot on Saturday nights, and Jack and Jerry Brisco secretly convinced enough shareholders to sell to Vince McMahon in 1984 for $750,000. It became known as “Black Saturday.” Loyal fans revolted against the WWF programming on TBS and the ratings were not as good as the previous show. McMahon, through Jim Barnett, sold Crockett Jr. the timeslot for $1 million.

While the business was Crockett, the creativity came from Scott and then Dusty Rhodes as the primary matchmaker. Massive shows, like Starrcade 1983, headlined by Ric Flair winning the NWA World title from Harley Race, were nationally covered, and set in motion the idea of supershows like WrestleMania.

Those were the heights, said Rhodes. At the 2004 Mid-Atlantic Legends Fan Fest, Rhodes said the Crocketts “were like the Kennedys” in the Carolinas, and in a Chicago radio interview from 2010, Rhodes said that the JCP time was the best. “The Crockett days. We were riding around like rock stars.”

Rhodes, though, took a lot of the blame for the fall. He was taking on WWF without the business acumen. “He was the wrong guy to be a booker. He is the one who put Jim Crockett out of business,” said former NWA World champion Ronnie Garvin in 2014. “He is the reason Jim Crockett had to sell and was losing his butt.”

At the 2004 fan fest, Rhodes admitted that things changed. “Our business took a big fall when the Crocketts were bought out by TBS.”

In 2013, Rhodes was asked by Bleacher Report about the blame he gets. “That’s something I’ve stayed out of the mix on. Because it was not important to me who they blamed. What we were doing wrestling-wise speaks for itself, and I’ve left it at that,” said Rhodes. “I took a little minor league area down there, put genius to it. And yes, I still think I’m a genius after all this time, crazy egotistical maniac that I am.”

He also added, “I did not cause the downfall of Jim Crockett Promotions. Not by a long shot. I don’t even want to get started on that.”

In 1983, Crockett shared his philosophy in a newspaper article. “You have to give people what they want,” he said. “It has to be fast-paced and entertaining. And what’s successful today may not be successful tomorrow. You have to go with your gut reaction, and you won’t always be right.”

Crockett Jr. remained NWA president until 1991, and that was the end of his association with the big-time.

There were two other attempts by Crockett Jr. to return to wrestling. In 1994, he founded the World Wrestling Network to try to capitalize on the new Internet, but it was too early and broadband access was not available. He also tried to promote shows in Dallas around the same time, where he had moved the company’s headquarters to look more important, in a major TV market.

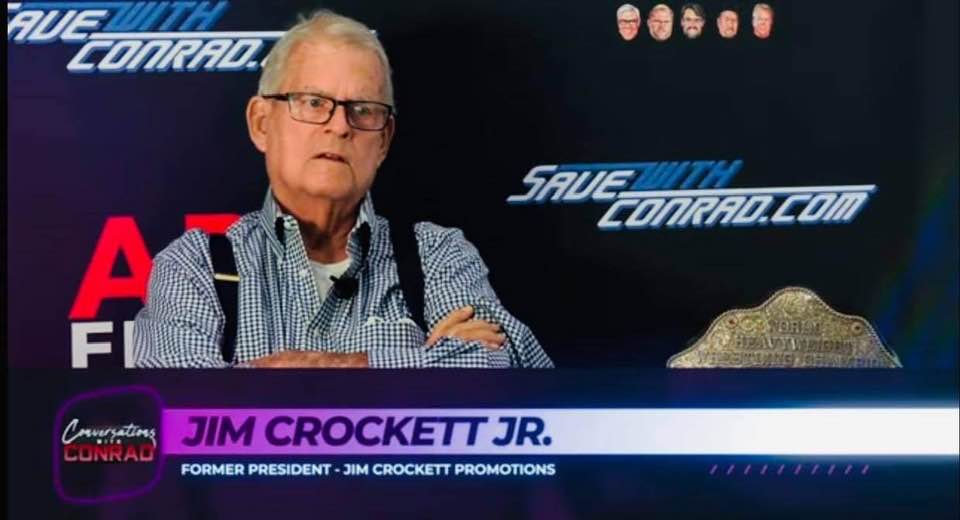

Based out of Dallas, Texas, Crockett was a realtor and rarely made any wrestling-related appearances. Conrad Thompson had Crockett as a guest in February 2021, on his Ad Free Shows platform on Patreon. On “Conversations with Conrad,” Crockett was quizzed about all aspects of JCP.

Talent, in general, usually spoke highly of Jim Crockett Jr.

Ivan Koloff, in an interview with Steve Slagle, said “Jim Crockett, who gave me some of my best money-making years, it’s hard not to like a guy like that.”

Roddy Piper, in 2011, told Mike Mooneyham that he wouldn’t let the WWF book him in Crockett’s territory. “I wouldn’t come and work against Crockett,” said Piper. “I wouldn’t work against Jimmy Crockett and I wouldn’t work against (Pacific Northwest promoter) Don Owen until the time came. I got a tremendous amount of heat, but there’s got to be some kind of honor there.”

Sonny King noted that he was taken care of while out injured. “Jimmy Crockett Jr., I have the utmost respect for him,” said King in 2010. “This guy was a good guy. When I went to the hospital, he comes and he says to me, ‘Don’t worry about anything, and if you need something go direct to me, and don’t talk to anybody.’ Fine, that was it.”

A young Scott Hall spent some time in JCP. He told Wade Keller of the Pro Wrestling Torch, “A lot of times, Jim Crockett when I was working for Crockett Promotions and I was just breaking in, a lot of times, Crockett doesn’t even watch the matches. You know what he does. He stands in the back and listens. He said it’s all about who can make ’em yell the loudest and the longest.”

But not all of them.

“I always liked David and Jackie Crockett, but I only met Jim Crockett once or twice, and everyone thought he was a [jerk]. But Flair had him as the best man in his wedding. Who has the promoter as his best man?” Scott Steiner asked Kevin Eck of the Baltimore Sun in 2008.

Myra and Jim Crockett. Facebook photo

Crockett and his first wife had one son, James A. Crockett III — known as Jace. Crockett and his second wife, Myra, had two daughters.

News of his death circulated on March 3, 2021, as AEW Dynamite featured a few of his top stars — Tully Blanchard back in the ring, accompanied by JJ Dillon (who worked in the WCW office), and Arn Anderson coming out to flash the symbol of the Four Horsemen. Robert Gibson of the Rock’n’Roll Express apparently broke the news.

TOP PHOTO: Jim Crockett Jr. and Tony Schiavone.

RELATED LINKS

- Mar. 14, 2024: Jackie Crockett, dead at 76, ‘just one of the boys’

- Nov. 29, 2022: This week’s ‘Tales from the Territories’ offers little more than a history lesson on Jim Crockett Promotions

- Apr. 3, 2001: End of an era on TBS: Solie, Georgia and ‘Black Saturday’

- Apr. 4, 2001: End of an era on TBS: Crockett, Flair and ‘The Clashes’

- Apr. 5, 2001: End of an era on TBS: Fond memories of the SuperStation

- Apr. 12, 2001: End of an era on TBS: The letters