Pat Patterson, one of the greatest wrestling minds in history, has died of liver failure. He was 79. He liked to bring up a slightly-mixed-up thought to make one think about one’s goal in the ring: “The roar of the paint and the smell of the crowd.”

Give that some thought, and you too might understand what the wrestling business used to be about for Pat Patterson, who was born Pierre Clermont in Montreal on January 19, 1941

“Everybody thinks it’s backwards, but I really accept and believe that. The roar of the paint to me was like you walk into the building and you look at the building, and it’s like wow. What a nice building, it’s sold out. That’s the roar of the paint. The smell of the crowd is having those fucking people yelling” — he inhales deeply — “that smells good. You know what I mean? It’s the crowd. You have to pay attention to the crowd when you’re in the ring.”

There were few better as an in-ring performer than Patterson, and as a wrestling mind, coming up with finishes and ideas — like the Royal Rumble — he was unparalleled. (Some might note his use of profanity was another great skill.)

Patterson’s bump-taking was off the charts, but more importantly, he knew when to take those spectacular bumps.

Chavo Guerrero Sr. explained in The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: The Heels. He first worked with Patterson on the undercard of a big battle royal show at the Olympic in Los Angeles. Patterson entered the ring and held his nose, indicating that Guerrero smelled a little funky. “It embarrassed the shit out of me, because at that time, I’m small, I’m Mexican, I had a complex anyway. And you do it in front of a crowd of people! I’m getting hot,” said Guerrero. “Then he says, ‘Just go with it.’ I’m saying, ‘You son of a bitch.’ He does it again. I go to lock up, and he goes, ‘Ugghhh’ and he holds his nose. But as he does this, I’m watching and he’s turning and doing it to the people too, not directly but indirectly. At the right time, he tells me to give him a dropkick. By that time, I’m ready to kill him — not that I could have. I give him a dropkick and he takes a bump to the second floor and those people, you could have mistaken them for being in the Superdome. It just popped, and I went ‘Wowwww.’ After that, the match was easy.”

Growing up in Montreal Clermont considered the clergy but was talked out of it. Instead, his adventurous nature took him to a church gym where amateur wrestling was taught. It was 50 cents to get in. He had a pro match at age 17 against one of the other students, and was soon booked around Montreal on promoter Sylvio Samson’s smaller shows. (His other wrestling connection? Roger Barnes, who later become Ronnie Garvin, used to date Patterson’s sister.)

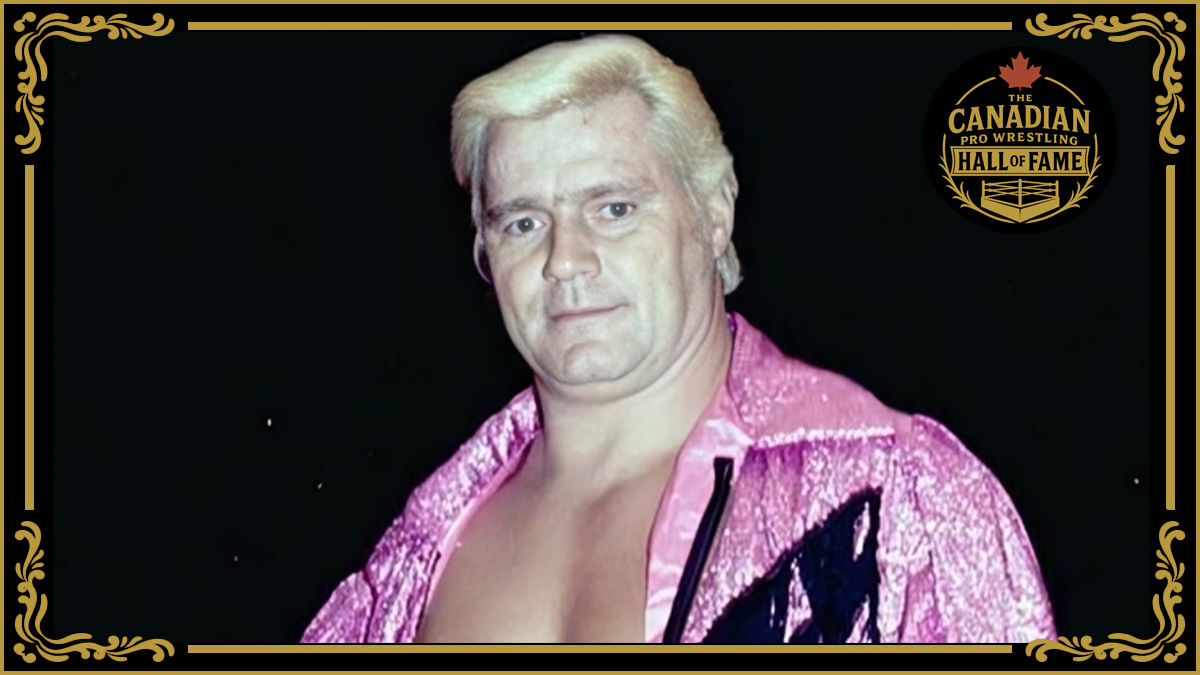

Like any kid, he had his hero. “When I used to watch [Killer] Kowalski in Montreal, he was my idol,” Patterson said. “Kowalski the big name, a big star. He had purple boots, a purple jacket and I had the same thing. I came to Boston and I was on the same card that he was—obviously, I’m in a preliminary match. I’m in the same dressing room as Kowalski and I’m freaking out.” He patterned himself after Kowalski really until the “Pretty Boy” Patterson gimmick developed around 1962. Wearing pink wrestling tights, pink lipstick and rouge on his angular, high cheekbones, and puffing away on a cigarette, held in a long, diamond-studded holder, he had found a way to create instant heat. Over time, he learned to get the heat without the props, like his French poodle.

“He was a flawless heel, vicious and aggressive, and did everything with precise timing,” wrote Superstar Graham in his autobiography. “To this day, there’s never been anybody who can throw better mounted punches from the ropes. When his head was run into the ring post, it recoiled, with hair flying backward, like it was about to pop off.”

Patterson used a few shortcuts to getting a crowd to react: he could scream and rant with the best of them on the microphone, his heavy French accent only adding to the charm; he would hide a mask in his trunks and at the right moment, put it on behind the referee’s back and headbutt his opponent into oblivion with whatever was hidden inside; and he could bleed with the best of them, his blond locks soaked with sweat and blood.

“He was also of that era of the pure heel, and there was no fudging, you didn’t cross that line. You remained a heel, period,” said his former partner Graham. “It was just his timing, and his believability, his punches. His promos were the basic Ray Stevens, baddest bully on the block, just hard-nosed. He was just so convincing. … His accuracy, his timing, he just had the magic in him, he really did.”

His first big run came in the Pacific Northwest in the early 1960s, but it is in the San Francisco promotion where became a legend. Patterson is proud that he was able to stay on top for so long, and the city was home for many years to Patterson and his life partner Louis Dondero. “In those days, you’d work in the same towns every week and you see these people in the front row. ‘Oh, Pat, we love you!’ I’m like, ‘God, what am I going to do this week? How many times can these people watch you?’ Whether you’re a heel or a babyface, it’s hard to—I was hoping that one day I could leave San Francisco, but I was there about 14 years. I thought that was a pretty good accomplishment to last that long in a territory.” In ‘Frisco, he would form championship teams with Graham, Rocky Johnson, Peter Maivia, Moondog Mayne, Pedro Morales, Tony Garea, and Pepper Gomez, but it is his pairing with Ray Stevens as the Blond Bombers that stands among the best teams of all time. Stevens and Patterson entered the Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame as a team in 2006.

While in San Francisco, he learned the philosophies of booking a territory from promoter Roy Shire. Patterson would book ‘Frisco, and in Florida for a short while, before ending up in the inner circle of the WWF after his in-ring retirement in 1984. He’s an unsung hero, say those who worked with him in the WWF. “Much of the credit for the success of the WWF should go to Pat Patterson,” said J.J. Dillon in his autobiography, adding that Patterson had the rare ability to communicate with Vince McMahon. “Pat was one of the most colorful, energetic, enthusiastic, funny, caring and understanding individuals I’ve ever known,” wrote Vince Russo in Forgiven. “I learned so much from him, and I think back then he was drawing from my energy. Pat and I always used to bounce ideas and angles off each other. To this day, I don’t think he realizes what a thrill that was for me.”

In Montreal, Patterson wrestled in International Wrestling, and was known as “Le Rêve du Québec,” meaning Quebec’s dream. Later, he was an announcer for French broadcasters of WWE programming.

Though he retired from the WWE in the fall of 2004, Patterson would continue to be called upon by the company, especially for help with finishes. Content to travel, visit friends and family, and hit the golf course in his golden years, Patterson had a huge health scare in August 2006, when he had emergency heart surgery to remove a cyst from his main artery.

Patterson was a regular at Cauliflower Alley Club reunions in Las Vegas, often leading the room in singing “My Way,” and holding court in the bar into the wee hours. The CAC presented Patterson with one of its top awards, the Art Abrams Lifetime Achievement Award, in 2008.

When Shawn Michaels received the same away in 2018 (though it was renamed the Art Abrams/Lou Thesz Lifetime Achievement Award), he paid tribute to Patterson, who was sitting at a table at the front of the banquet room. “Pat Patterson is, as far as I’m concerned … as the business changed, you changed, and you always stayed ahead of the curve. You never got bitter, grumpy and all that kind of stuff, man,” said Michaels. “You inspired hope and joy and going out and having fun … you were a huge influence on all of us, and I don’t know if you think about that that much, but Pat, I’m telling you, you were absolutely one of the greatest things this line of work has ever had. I don’t get up here without you, man.”

WWE feted Patterson at a May 2015 event in Montreal, the whole crew coming out to applaud him, and Bret Hart presenting him with a personalized Montreal Canadiens jersey and a framed Intercontinental title.

He brought a joie de vivre to events, was adept at teasing and joking without being cruel. “He had an infectious personality where you always wanted to be around him,” posted Kurt Angle in a Tweet. In short, everyone loved Pat Patterson.

His last appearance with WWE was the Royal Rumble in Houston in January 2020.

Patterson’s autobiography, Accepted: How the First Gay Superstar Changed WWE, came out in 2016, written with Bertrand Hebert.

In the last number of years, Sylvain Grenier was Patterson’s caretaker, and the two grew close. Grenier saw Patterson as a father figure (his own father having died in 1999) and Patterson saw Grenier as the son he never had. Grenier has power of attorney over Patterson’s affairs.

Patterson’s passing early in the morning of December 2, 2020, was due to liver failure, complicated by his previous cancer issues. He had lost a lot of weight in recent months, had memory issues, and had moved to a nursing home in Hallandale, Florida. On November 27, a liver clot saw him moved to hospital in South Beach, Florida, where he fell into a coma, and never recovered.