Just around the corner from Toronto’s Maple Leaf Gardens was Joe Black’s studio, Graphic Artists, on Yonge Street. The location meant that Black was a regular at sporting events around the city for years.

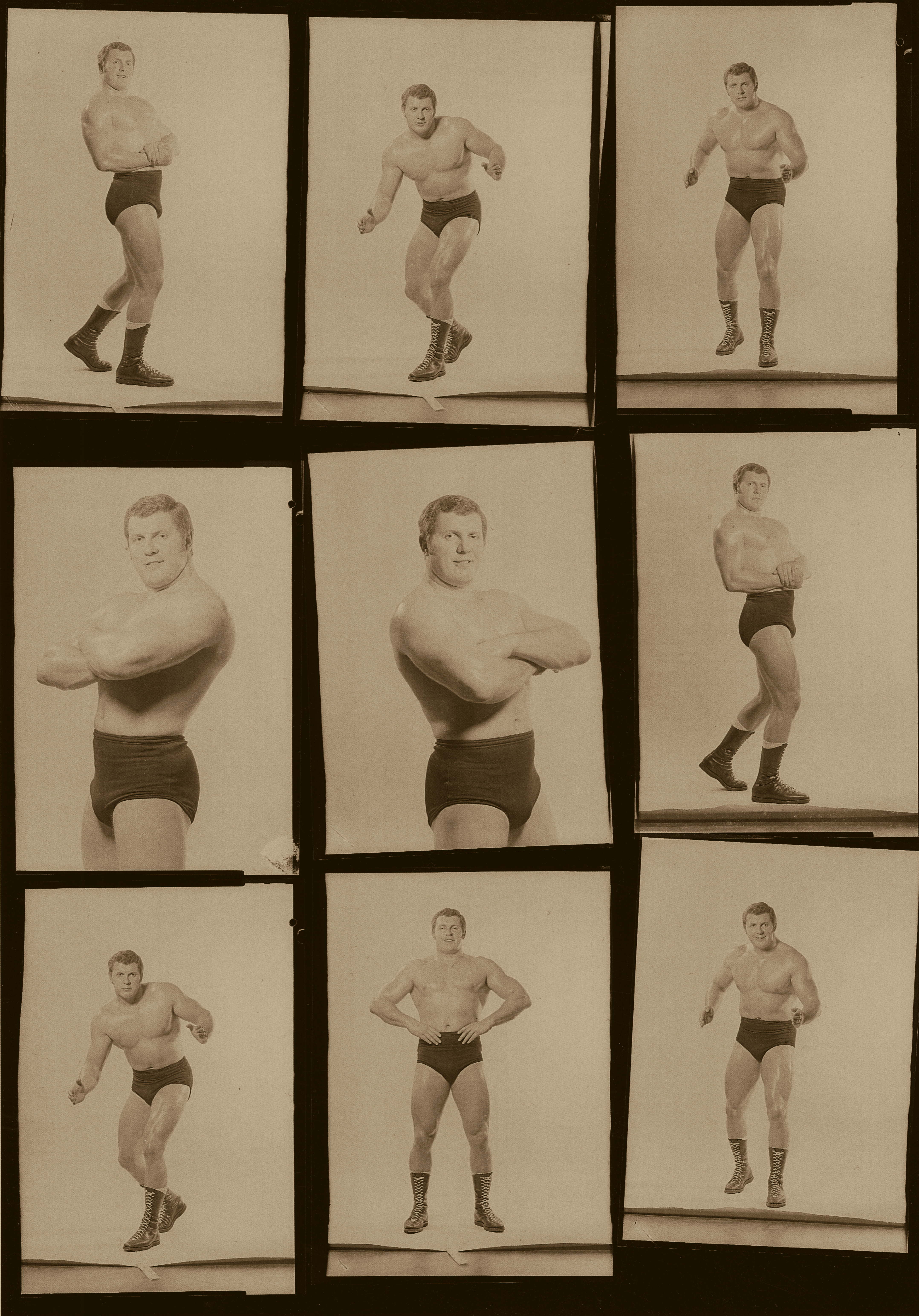

Though he didn’t shoot tons of live wrestling, Black did photograph plenty of wrestlers in his studio, from the big — Shohei “Giant” Baba — to the little people, making the short trek to pose.

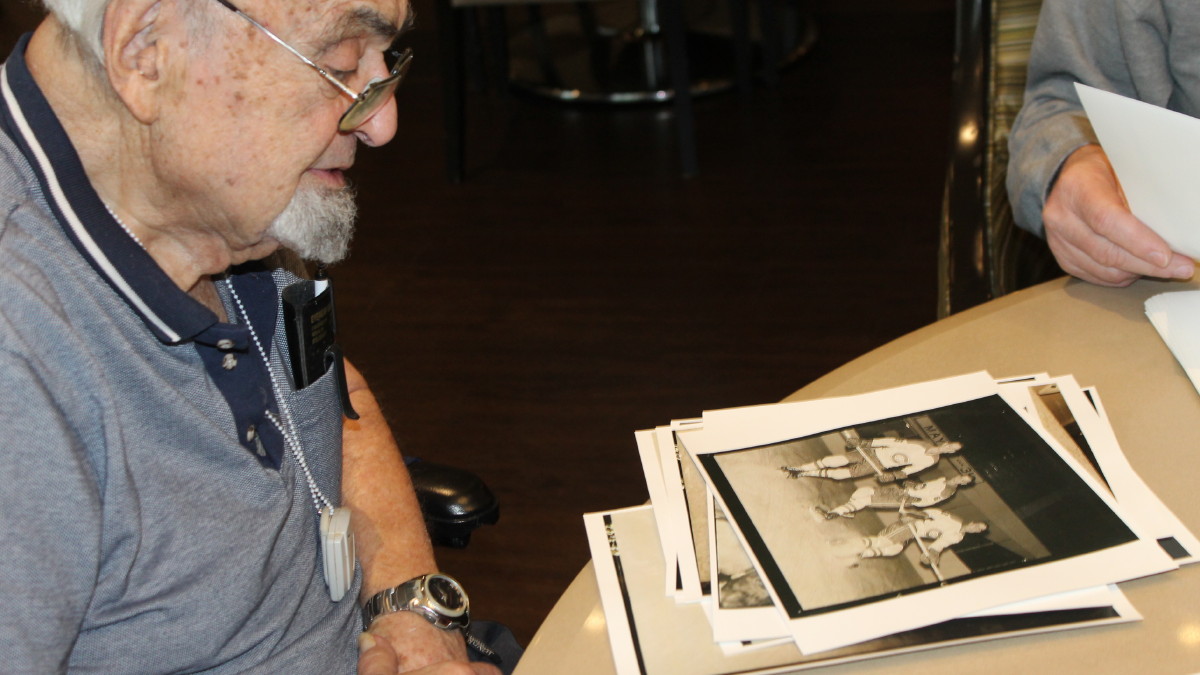

“I would take their publicity pictures, and when then they’d go to the small town, they’d sell pictures,” Black recalled in an in-person interview in the summer of 2018, with this writer and photo archivist Don Chubby.

Quick with a smile, Black said he liked to tease the wrestlers. “I used to kibitz around, and say, ‘It’s alright, I’ll take the pictures during the rehearsal that you have.’”

Joe Black photos of Dewey Robertson.

Those posed wrestling shots are only a tiny, tiny fraction of the photos he took during his lengthy career. With his passing on October 20, 2020, at the age of 94 in Toronto’s Sunnybrook Veterans Hospital, it’s time to revisit the legacy of Joe Black.

He was born January 20, 1926, in Toronto. His father was from Prussia, and his mother was originally from Vienna, Austria. They ran a confectionary store on Bloor Street at Montrose, near Christie Street. It was right next to the expansive Christie Pits park, where Black was witness to the 1933 Christie Pits riot, which lasted six hours, pitting Jews against anti-Semites.

With Adolf Hitler rising to power in Germany at the time, anti-Semitism was increasing in Toronto. The city itself had plenty of restrictions, from swimming pools that banned Jews, to Eaton’s department story preventing its Jewish employees from interacting with customers. There were “swastika clubs” in the city, and Jewish homes were targeted with garbage. The city’s large Italian population was hassled as well, immigrants seen as destroying the Anglo Saxon, Protestant way of life. In short, tensions had risen in Toronto.

On August 16, 1933, there was a baseball game in the park, with a Catholic youth team from St. Peter’s Church facing off with Harbord Playground, featuring primarily Jewish boys but also some Italians. Fans for both sides were on the lawn. When a large sheet with a swastika on it was unfurled, the Jewish fans reacted, ripping up the banner. “As soon as some of the Jewish players on the youth team saw that swastika, they went after those guys and tore that flag apart,’’ Black told the Toronto Star in 2013.

From there, it grew, as supporters on each side went at it, and called in reinforcements. “It went on for hours and hours,’’ recalled Black. “This was summer, so it stayed light till around nine o’clock. But they were still at it at two, three in the morning.’’

Remarkably, no one died. The city banned the display of the swastika in the following days.

Black himself, a young kid, dodged any injury, but was witness to it all. When he turned 16, he enlisted in the Canadian army. “I was transferred over to the Air Force afterwards,” he recalled.

Days after her father’s passing, Black’s daughter, Susan Perez, shared more details. In the Royal Canadian Air Force, Black was an aerial photographer, primarily out in western Canada. “Photography, from the very beginning was his lifelong passion,” said Perez. In a Hockey Hall of Fame interview, Black said that the spark was lit when he used his mother’s box camera, but more importantly, he got to see the photos he took be developed. “I think they probably asked him, ‘What would you like to be doing?’ And that was what he chose.”

Upon the conclusion of World War II, Black met his future wife, Beatrice, in a bowling alley. They were married in 1946, and had a son, Martin, in 1949, and daughter, Susan, the following year.

In 1946, Black started the Graphic Artists studio, which had three different locations through the years: Yonge Street, Adelaide Street, and finally 58 Bathurst. His son, Marty, worked in the studio for many years.

The lessons Black took away from the hatred in the Christie Pits riot stayed with him, and he was not one to judge, said Perez.

“He liked people, one at a time. It didn’t matter what your background was, it mattered who you are, what you stand for, the qualities that you possess,” said Perez. “He just really embraced people. And it didn’t matter, just because you were similar to him, didn’t make you a good person. What made you a good person was regardless of that background. He always taught us that you don’t judge a book by its cover, you don’t judge a person by their skin color, you don’t judge them for what their parents did or their country did. You judge them for what you see.”

A concrete example — he befriended Catholic priests. “I made a book and when the couple came in to be married, all the instructions were done with my book,” Black said. “I did a lot of things with different priests, and I’m not a Catholic, but I helped them as best as I could.”

Early in his photographic days, Black shot tons of celebrations. “In the Jewish community, he was well known because he started with weddings and bar mitzvahs, so a lot of people knew him,” said Perez. “He also did a lot for the United Jewish Appeal. And in the promotion end of it, like taking pictures of people that would run in the Jewish news, as well.”

One of those weddings Black photographed was for Roger Baker, who has contributed many photos and stories to SlamWrestling.net through the years. Baker had met Black at the Young Men’s Hebrew Association, where Black was on the hunt for athletes. In a photo that ran in the Toronto Star, weightlifter Syd Charendoff, who was headed to the trials for the Pan-American Games, pressed Baker above his head.

“I always had a fond feeling for him, because during our wedding, I handed him off my first camera that I ever owned, it was an Olympus camera,” recalled Baker. “I asked him if he would take a picture of [my bride] Gloria and I at our table with all the guests on either side of us. With a little camera he guessed what the F-stop should be — well, that’s not hard to figure out if you know what kind of film you’re using, in that case it was Kodachrome, but he got a beautiful picture. I’ve got a print made out of it.”

Baker noted that later, when they met up at a wrestling show, that Black invited him back to the studio to develop his film, and offer some advice. “I was flattered, because here’s a pro taking an interest in me,” said Baker, who’d already had his work printed in wrestling magazines. “He developed the film, pointed out a few things that he felt like I can improve on. I was there maybe half hour, 40 minutes, he showed me his equipment. He had a lot of equipment — he was a perfectionist when it came to doing the pictures. He was very good with lighting.”

For the Toronto Maple Leaf hockey games, Black and his team set up the first strobe lights to better shoot the games, three at each end of the rink. At the time, the cost of the lights was a major issue, at $265 each; he saw the value in them. It was just one example of his innovations, and he learned to understand hockey.

“Each game has a character to it. You have to know the game. And I was able to give them stuff that they wouldn’t get otherwise,” said Black, who also learned tendencies of the big name players in order to know when to take a photo.

Craig Campbell, the manager of the Hockey Hall of Fame’s Resource Centre and Archives, is a fan. “Joe Black and those who worked with him under the company name of Graphic Artists provided beautiful hockey photography from the early ’60s through to the early 1980s,” Campbell said in an email. “Joe was very proud of composing and taking posed action shots while laying on ice while focused up at the players skating towards him. His coverage of international and junior hockey and the NHL was wonderful.” The hockey collection from Graphic Artists, preserved at the Hockey Hall of Fame, comprises over 60,000 original images. (You can see a small gallery at the HHOF here.)

Black shared some of his techniques.

“Hockey pictures, like they have now, don’t come anywhere near what we did,” Black said, referring to posed shots. “I would be on the ice, but I always stayed at a very low level … if you’re low, and if you shoot up, you’re stretching, because his feet are closer to the camera than their hands, so it gives the illusion of speed. And I would put a puck on the ice and I’d say to the guy, ‘I want you to skate over that, I want you to put your stick down as if, but don’t touch the puck!’ When they did that, I got an excellent picture of them skating over with the puck.”

With football shots — for many years, CBC hired Graphic Artists to take photos of every player in the Canadian Football League (CFL) so it had images to use on TV — Black did something similar. “When I’m shooting football, I get the guy, I say, ‘Jump up, you have the ball in your hand, throw it out.’ They throw it out, it just looks as if it’s coming in.”

Again, hockey (NHL, plus World Hockey Association, junior hockey and the 1972 Summit Series) and football are only a small part of what Graphic Artists did.

Ford Motor Company used its services to take photos of new automobiles, which could mean printing up thousands of copies in the studio for every dealership in the country. Black could tie in connections in sport, like Gordie Howe or Bobby Hull, into a promotional photo.

Black worked to support the military in Israel, by being a part of a team that arranged for Sherman tanks that were in disuse in the United States to be shipped to Haifa — listed as farm implements. “My role was taking photos for the maintenance books and things of that nature,” said Black. “I’d be working through the night to get certain things done. But I was involved with it.”

A Joe Black birthday cake.

But for his children, little tops 1964. Black came home from work on that early September day, and mentioned, “You know, I was at Maple Leaf Gardens today, there was a press conference with this English group. I think they’re called The Ants.”

Perez immediately replied, “They’re called The Beatles!” Both of Black’s children got to see The Beatles play at MLG.

“He wasn’t overly impressed with famous people, because he was exposed to them a lot,” said Perez. That list is long, from Queen Elizabeth II to Pierre Trudeau to Wayne Gretzky. On occasion, Perez would tag along, and recalled being up close to acting legends Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton. “I knew that he didn’t have a nine to five job. He was out in the evening taking pictures.”

The Black family — Joe, Susan, Martin and Bea. Courtesy Susan Perez

Yet there was down time too. Black liked to tinker with things that were broken, trying to fix them up. He didn’t just shoot sports, but also enjoyed tennis, golf, boating, flying and swimming.

And he had time for his community.

Perez got Black started as a volunteer at a retirement home called Cummer Lodge; while she dropped away, he kept at it for 20 years. “There were a lot of Jewish residents, and he spent two decades as a volunteer. He ran their Sabbath service. Every other week, they would bring the residents to auditoriums where he built the ark that you have for the scrolls, the Torah. And he would help to run the service,” said Perez. “He did a lot for the Jewish community in a very quiet way. But it was appreciated. And he was also quite generous. Whenever he donated anything, it was always anonymously. He deserves more recognition, but he was not looking for recognition. He was doing things from his heart.”

Part of the reason that Black isn’t more celebrated for his photographic genius, especially compared to predecessors such as Nat and Lou Turofsky and Michael Burns, is that the prints would be stamped with Graphic Artists, and not his name.

“He obviously made impressions on a lot of people. But he was very much in the background,” concluded Perez. “It was not about him. I think a lot of times it was about the work.”

Bea Black died in 2013. Black is survived by his son Martin (Mary) and daughter Susan (Jose), grandchildren Genny (Nick), Teena, and Benjamin, and great-granddaughter Isobel. There will be no funeral. Donations may be made to the Jewish organization of your choice or Sunnybrook Veterans Centre.

JOE BLACK PHOTOS AND PHOTOS OF JOE BLACK

[modula id=”78316″]