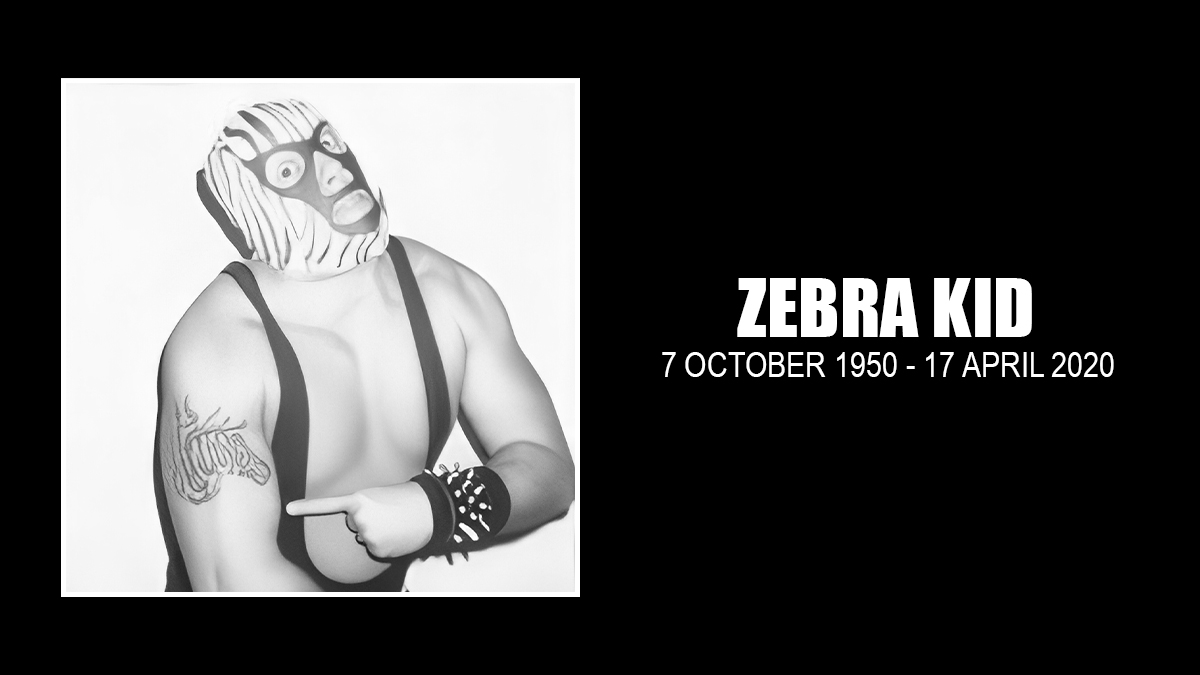

Knowing that his battle with esophageal cancer was coming to an end, “Zebra Kid” Kevin Clark, a worker in the Midwest since the late 1970s, created a series of videos on Facebook that detailed his career. “It’s almost time to take it home,” he said in the first, under his hood. That journey ended April 17.

The videos provide a wonderful recap, with some funny stories, such as his mother storming the ring to save him not long after her husband and his father passed away, as well as poignant thoughts on his time in professional wrestling.

“What this business means to me — the sense of family, the sense of camaraderie, it means so much. It makes me want to tear up,” he said, set up facing a camera, some of his memorabilia and awards behind him.

Knowing that their friend’s life was near an end, as Clark had decided against further treatment, that wrestling family conspired last fall at the Midwest Wrestling Reunion to celebrate his life. Organizers Carmine DeSpirito, Joe Mauriello and Chazz Moretti announced that Nacho Guerrero was to receive a Lifetime Achievement award, but then they hatched a plan for a second one for Clark.

Moretti recounted that they made Clark pay his $25 for entry, and asked him to present an award to another honouree. Instead, Moretti said they pulled the “swerve” and “presented the award to Kev, who was dumb-founded. He gave such a nice speech.” The kicker was they’d set aside Clark’s ticket money in a white envelope, and presented him with his “payday” at the end.

It was a way to pay back someone who was a mentor, said Moretti, a manager. “Anybody who sat in the back with him, immediately felt like they knew him forever,” he said. “He was that open, and he was so willing to give advice, and to talk to and to help out the younger the guys that were in the locker room.”

Clark grew up on Chicago’s west side, and saw pro wrestling late on Saturday nights. Later, when their black and white television was more portable, they’d set up the TV outside for others to come and watch too. Around 1958, he started going to the Marigold Arena in Chicago with his family, where it was usually young wrestlers, including some trainees, going at it.

Already in love with pro wrestling, it was even more magical when, in 1959, his grandfather took him to the Intentional Amphitheatre where the main eventers fought. Excited at the possibilities, the nine-year-old Clark bought himself an autograph book at a dime store. At ringside, he asked for autographs, but every wrestler said, “After the match,” and then never did sign. A maintenance man saw it and felt sorry for Clark, who did’t get any autographs, so he brought him to the dressing room at intermission.

There, it was a different story, said Clark. “Every single one of them shook my hand, signed the autograph book, talked to me, and I was just in awe. Here are these superheroes that I watched every Saturday night on TV.” Meeting Buddy Rogers, Art Thomas, Johnny Valentine and others “sparked the fuse.”

“I was like, Oh my God, I want to do this,” he recalled. To reach his goal, Clark wrestled in high school and Triton College, where he studied liberal-arts. One one occasion, he even wrestled Tuffy Truesdale’s bear at a sportsman show.

Clark kept going to wrestling matches too, and became a recognizable face to the wrestlers. One time, he brought a girlfriend to a show, and they were seated at ringside. She had on a white dress. A bloody Mad Dog Vachon was thrown out of the ring on the side where Kevin was. Mad Dog buried his face in the girl’s lap. As he was getting up, he winked at Clark and got back in the ring. Clark never saw her again, but he sure saw more wrestling.

At one show, Clark was at the restaurant at the Amphitheatre when Bob Sabre, a lower-level worker, approached him. “He started asking me questions,” recalled Clark, asking about his amateur wrestling background, his weight, and then asked him about breaking into the sport. Clark was overjoyed, and Sabre handed him his business card, and said “Okay, you’ve got one shot” — and it was the next morning.

Clark showed up on that day in 1974 and kept going back. His first match was June 28, 1975 at a fairgrounds, in a tag bout, facing Sabre. In the crowd were Clark’s parents and sister.

He acknowledged that Sabre changed his life.

“I owe everything to Bob. He trained me, he was a mentor for me, he was a friend. Later, after I broke into the business, we promoted together. When I got married, Bob was my best man,” Clark said on his video. “Years and years later, Bob came down with colon cancer, and he grasped at every straw, he weighed a solid 240, 245 pounds, and in no time, he went down to maybe 90 pounds, laying in a hospital bed in a fetal position. I would go up and visit him almost every day once they put him in the hospital at the final stages.”

Sabre didn’t have any children, and his widow told Clark that he considered the wrestlers he trained to be his kids. Clark was asked to deliver the eulogy for Sabre, but instead told funny stories about Sabre, which prompted Sabre’s other “kids” to offer their own memories.

Initially, Clark wrestled as Jackie Stevens for about a year, and then he was Kevin Clayton, until 1984, when he became Zebra The Kid.

The early part of Clark’s career was learning in bouts throughout the Midwest, whether it was for Bob Geigel in Central States, where he worked against the likes of Harley Race (“I’ve never been so thrilled to be pinned, because it hurt”) and Bulldog Bob Brown, and even for Angelo Poffo, whose kids, Randy and Lanny, he knew from the Chicago Amphitheatre. “It has been a long, crazy ride, and I am so happy to have been a part of this business for almost 50 years. I’ve wrestled throughout the U.S., I’ve wrestled in Canada, I’ve wrestled in Mexico,” Clark said.

He explained that there were three stages to his career.

“I was quite accepting of the term jobber because when you first start in the business, you’re going to have a fear of the crowd … you’re going to have a fear of a certain degree, going against a big name, not knowing what’s going to happen. You’re inexperienced,” he began.

The next stage is journeyman, where you learn to and are allowed to get some shine on yourself.

The last stage is a being a worker. “Your head is in the right place, your body is in the right place to actually be on somewhat of an equal part with household names. That transition was not always made. I knew a lot of fellows that were just jobbers that never made that transition.”

It was as Zebra Kid that Clark made the most impact.

There is a profile of the masked man in Official Wrestling magazine, dated July 1984, written by … Kevin Clark.

“The Zebra Kid #1 is a 211 lb., lightweight wrestler from Cape Town, South Africa,” the story reads. He claimed that he had left South Africa and was hiding his identity because of his anti-apartheid stand which would cause trouble back home.

“The first reason for my name is obvious given my political beliefs — the black and white stripes blend together in harmony like black and white South Africans will one day soon! The second reason for my name is that, as a young child, I had the opportunity to see the original Zebra Kid wrestle and I adopted the name to carry on his legend.”

The original Zebra Kid was the much bigger George Bollas, who was an NCAA heavyweight champion while at Ohio State, and wrestled pro from 1947-68.

The smaller Zebra Kid, Kevin Clark, was a mainstay in Pro Wrestling International in Chicago and then the influential Windy City Wrestling. Sensuous Serena was his manager for a time.

Through the years, Chicago’s Joe Mauriello has served in various roles in pro wrestling, from official timekeeper to private security; but he’d always been a wrestling fan.

Clark was a friend, and Mauriello considered what made Zebra Kid successful. “I think he brought some class with him to Windy City. He made it more believable. He made the fans hate him. They didn’t know who the hell he was, from the guy down the street with a bag of popcorn. They had no idea who he was, other than a guy with a mask on threatening the safety of [their] girlfriend.”

Mauriello often went out with the boys after the matches, at a time when the heels and babyfaces still were kept apart. “He wouldn’t have his mask on and nobody knew who he was.”

In the ring, Clark “was good. He stood out, to me, because he of smaller stature than the big bruisers and Andre the Giant-type guys,” said Mauriello. “He could move, he knew how to set up a match.”

When Mauriello was on security, Clark made sure he was in the loop. “I would be in on the talks of how the match was going to work, because I was doing the security. He always made sure I was there for that, because he didn’t want to get into any physical confrontations with the fans, he didn’t like that,” Mauriello said. “He would also ask me to do certain things, like if I was walking by, he was going to jump on my back and try to throw a punch at a fan or something like that. Just to draw some added heat. He trusted me so much to watch his back.”

Paying it back, Clark often went to the Windy City wrestling gyms to help out youngsters.

On Facebook, “Fireman” Jim Blaze called Clark “my wrestling uncle, brother, mentor and family member.” While training at Windy City, Blaze said that Clark — who was “Zeeb” to friends — “critiqued me on my negatives and positives through the early years in my matches.”

Trevor Blanchard was another youngster learning his trade in the 1980s. Blanchard faced Zebra Kid in a tag bout in his first ever match. “The only thing I knew was the finish and he was pinning me with a PerfectPlex,” said Blanchard. For a debut, he couldn’t have asked for better opponents. “I was getting so much noise from the crowd, cheering, clapping, and I was just like, ‘Wow, this is frickin’ awesome.'” Post-match, Blanchard didn’t get to say thanks. Down the road a few weeks later, a small man with a zebra tattoo approached him at the Windy City gym. “I didn’t know who he was until he told me,” said Blanchard. “I was so appreciative.”

Later, Blanchard learned another skill from Zeeb — how to throw a fireball.

“He was a little bit of a nutjob. He knew how to draw the heat, and he drew an excellent fireball,” said Blanchard, who never took one from Zebra Kid. Blanchard learned how to do it “properly so that you don’t get hurt and then you’re not hurting the other person, and as far as the distance. That all comes into play. When the guy turns around, you’ve got to make sure that you just throw it up and not at; if you throw it at, you run the possibility of setting a guy’s hair on fire. There’s little secrets to the whole trade of this industry, and that’s just one of them.”

Both Blanchard and Mauriello shared stories of traveling with Clark, who wore his mask in the car, and always had extras for co-conspirators.

Out of town for a Windy City show, Blanchard was driving with Zeeb and Ace Steel on a four-lane highway. “All three of us wind up putting on the hoods as we’re coming up to this car, we get over into the left lane as we’re passing, and all three of us look at this poor, old couple, who must have been in their 70s. They looked at us, we were dead even, and then the old guy either hit the brake or he took his foot off the gas, because they started backing up. It was so funny.”

Mauriello’s story was fraught with a lot more drama, as he, Clark, Iron Mike Sampson, and another security guard, were fighting to escape a blizzard in Chicago for a spot show. It took them seven hours to get there, just in time for bell-time. During the trip, they were stuck behind a little old lady on an off-ramp. Zeeb had Sampson put on a mask, and they egged on Mauriello at the wheel. “They said, ‘Come on, we’ve got to pass her!’ So I got in the passing lane, and as we passed up, they rolled down the back window of my car, and they both stuck their heads out with their masks on. This lady went off the road. You laugh, we laugh now, we laughed a little bit then. She just panicked when she saw these two masked guys stick their mugs out the window. She literally jumped up in her car, you could see the, ‘What the…?’ and she swerved and went off the road.”

“Mike is a little more sensitive, I guess you would say. He felt really, really bad. He wanted to pull over. I looked in the mirror and I said, ‘No, she’s fine. She’s back on the road again.’ It was just a fun moment. We had great conversations. They brought up some old wrestling stories and they wanted to know some cop stories. It made the trip a lot of fun.”

Though for all the three interviewees knew about Clark and Zeeb, they didn’t know much about his personal life. Clark had one son, Dusty, named after Dusty Rhodes.

Clark had been away from wrestling, living in Windsor, Missouri, and kept in touch with an active Facebook page, sharing his thoughts on politics.

His wife, Amy Clark, posted news of his death to Kevin’s Facebook page. “I was honored to have shared 16 years of his interesting and exciting life. He was able to successfully combine his two great loves, wrestling and politics. He always strived to make things better wherever he could and so enjoyed the adrenaline rush along the way. Rest in peace, dear Kevin.”

In one of the videos he posted, Clark noted that wrestling is not a one-man sport. “I have worked with the best. The thing you have to remember about wrestling is it’s easy to look good when you’re working with the best.”