Billy Sandow was close to the end of his life when he walked into sportswriter Lynn Mucken’s Portland office, looking for someone to tell his story to. He’d been involved in boxing and wrestling for over 50 years, and he’d mixed things up with some of the best from both of those sports. He’d worked most notably with wrestlers Ed Lewis and Everett Marshall, but he’d also been involved with prominent boxers like Joe Louis and Georges Carpentier. He’d ridden the highest during America’s Golden Age of Sports in the 1920s, but he’d never really stopped working. And he’d held onto quite a bit. Sandow was carrying with him boxes and suitcases full of papers and mementos that told the story of his life, all of which he opened up to Mucken.

Mucken’s attention was drawn to Sandow’s efforts in the 1920s to stage a fight between Lewis, who was wrestling’s heavyweight champion, and heavyweight boxing champion Jack Dempsey. The two men were the most famous names in their respective sports and a match between them, a rare boxer versus wrestler face-off, would have been a financial blockbuster. For much of 1922 and ’23, the group tantalized sportswriters with their challenges, boasts, and bets. Despite all of the attention paid to it, though, the match was never finalized. Researchers who have traced the history of the proposed match differ in their opinions on how sincere both Sandow and Doc Kearns, who managed Jack Dempsey, were in their commitment to actually making it come off. For his part, Sandow always claimed that he, Lewis, and Dempsey intended to see the match through. It was Kearns, Sandow claimed, who was interested in it exclusively for the publicity that talk of a match could generate. Mucken took it all in and turned Sandow’s story into “The Strangler vs. The Mauler.” The article was published in Sports Illustrated in August 1970.

It was Sandow’s first bit of national publicity in almost 30 years. He was so impressed with the young journalist’s work that he asked Mucken to help him write his autobiography. He hoped to use the archive as the basis for a book he’d title, The Golden Age of Wrestling. It would be a blockbuster, he imagined; a first-person tell-all from the heyday of professional wrestling, written by someone who had been there for it all. Busy with his work and with a newborn baby, Mucken politely declined.

What other stories were contained in those stacks of papers and fading newsprint is unknown. Ralph Friedman, another Oregon-based journalist, spoke with Sandow in the late 1960s, as well, and profiled him in an article for The Sunday Oregonian. In it, he made mention of “hundreds of pictures and the hundreds of thousands of written words in scrap books and suitcases,” that Sandow carried with him. “I’d like to have a book written about my life,” Sandow told Friedman. He clearly understood that his time was running out, and he was eager to have it documented while he still could remember it.

Sandow died in 1972, never having found someone to help with his long dreamed-of memoir. Some of the material he’d collected for it has survived and is in the possession of his grandson. Whether it is the entirety of his archive is unclear. It’s possible that he left some papers behind at his home in Portland, Oregon, which were either eventually thrown out or handed off to a friend or a local library or archive. (I have called several around Oregon and none were aware of being in possession of any of Sandow’s papers.) When wrestling historian Tim Hornbaker read Ralph Friedman’s article and saw the mention of a Sandow archive, he too made a number of inquiries in the hopes of tracking it down, but ultimately found nothing.

To try and pin down exactly how much has survived, in October, writer and historian Mark Hewitt and I traveled to Blythewood, South Carolina, to visit the home of Billy Sandow III, Billy’s grandson. Billy has lovingly preserved the stockpile of papers passed to him from his father, Bill II, who inherited them when Billy Sandow sold the property that he’d used as a training compound and vacation home, in Conesus Lake in New York.

The Sandows live in a beautiful high-ceilinged home set in a rustic part of Blythewood. When Mark and I visited, Billy had the entire collection set out for us on his kitchen table. Mark and I immediately knew that our trip had been worth it.

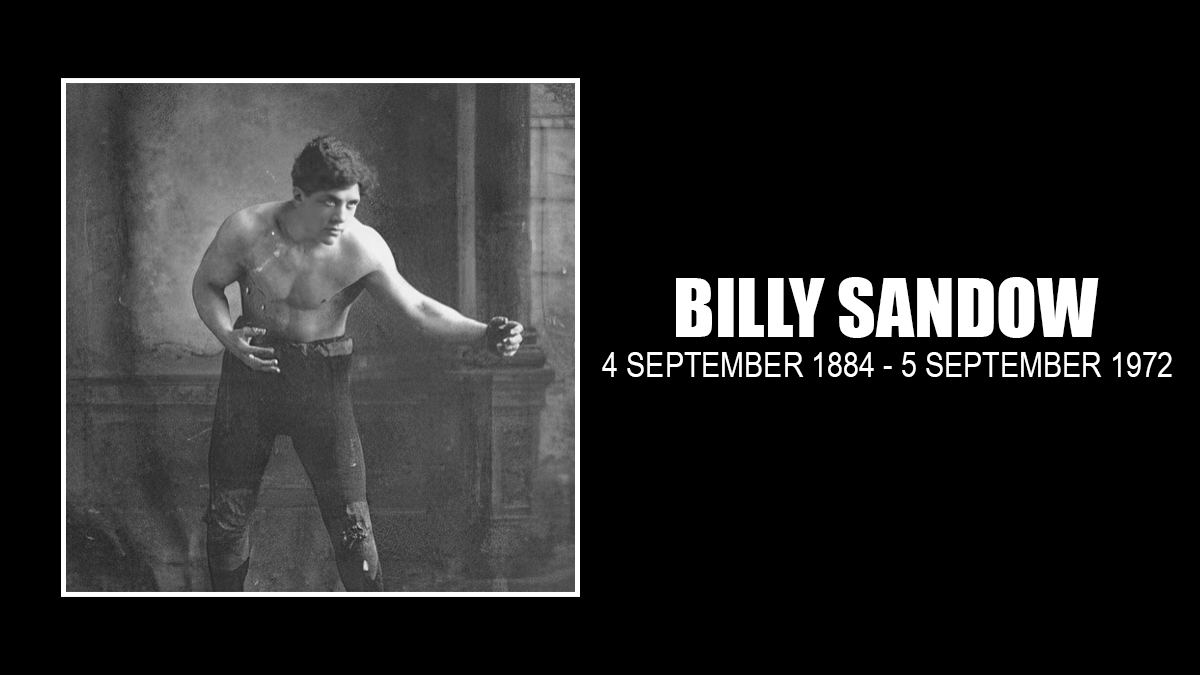

Billy Sandow was born Wilhelm Baumann in 1884 in New York. (His name change would come later, in 1918, in honor of strongman Eugen Sandow.) One of nine children, he was naturally strong, even at an early age. He gravitated towards athletics and in 1896, a chance meeting with promoter William Brady helped change the course of his life. Brady was most famous for his theatrical productions, but to sports fans, he was best known as the man who managed boxer “Gentleman” Jim Corbett to a victory over heavyweight boxing champion John L. Sullivan in 1892. Brady was a master of attracting publicity for his athletes. He modestly titled his auto-biography Showman, presumably, because there was no other word that could so accurately sum him up.

Brady dabbled in wrestling, as well. In 1898, he unleashed Yusuf İsmail, wrestling’s original “Terrible Turk,” on the American public to reams of overheated prose published in newspapers across the country. Brady dressed Ismail in a fez and colorful robes and paraded him down Manhattan streets. He sat him in a restaurant window that could be clearly viewed from the street and set him to eating a feast. Brady imagined a world instantly more sensational and exciting. He had no time for the hardscrabble farmers and mill workers who had dominated wrestling to that point. He sold Ismail to the press as something foreign, uncontrollable, and dangerous. Most of what he told them was lies, but almost all of it got printed.

Live, Brady made Ismail’s matches into free-for-alls that pulled the wrestlers, the audience, and frequently law enforcement, into the chaos. He turned İsmail into a media sensation that attracted crowds everywhere he went. When İsmail’s boat sank on its return trip to France, taking with it İsmail and 500 other passengers, Brady and his team planted the story that İsmail had been dragged down to his death by the belt full of gold he refused to surrender. It was a cold, heartless fabrication, but it’s a story that has stuck for over one hundred years. “It’s impossible to draw a hard and fast line between the theater and the arena,” Brady later reminisced. “The fundamentals of getting people to pay money to see something happen are the same in any field.”

Sandow would come to see wrestling in the same terms that Brady imagined it. More than boxing, and more than theatre, professional wrestling, when presented correctly, could be rowdy, immersive, and uniquely unhinged from the limits of facts and reality.

Still in his teens, Sandow moved to Chicago to attend school and began wrestling in 1902. He took to managing athletes, as well, including well-known names like Dr. Benjamin Roller and Yussuf Hussein. He cut an impressive figure, with a manicured physique and a head full of dark curly hair. His life would turn again in 1913, when he met a charismatic young wrestler from Wisconsin named Ed Lewis. The two would quickly become inseparable (A reporter for the Des Moines Register once described them as being like a young married couple). In Lewis, Sandow had found the wrestler with whom he could make his mark. Lewis adopted the nickname “The Strangler” as an homage to former heavyweight champion Evan Lewis but also as a signal to fans that he was a man to be contended with. Sandow changed Lewis’ finishing hold to the headlock, a move that the duo squeezed tight for every drop of publicity they could get out of it. Nimble with language and always happy to talk with any newspaperman who would listen, Sandow engineered a reputation for Lewis as a roughhouser who used his brutal hold to leave a body count of injured wrestlers in his wake. Sandow even patented a headlock machine, built by his brother Alexander; a wooden dummy head split down the middle with railroad springs connecting the two halves, Lewis would sometimes take into the ring with him to demonstrate his strength.

Sandow can claim as much influence over professional wrestling as anyone. A former vaudeville performer, he brought burlesque into the main event. He distracted referees and opponents with his ringside antics and infuriated fans by coaching Lewis from ringside during matches (Ed Lewis suffered from trachoma and the effects were so serious that at times he relied on Sandow’s signals to find his way around the ring). As Lewis’ second, Sandow invented wholecloth the archetype of the scheming manager. It’s possible to draw a straight line from his work with Lewis to Count Pietro Rossi in the 1940s, to Jim Cornette and Bobby Heenan in the 1980s, to Paul Heyman and Salina de la Renta today.

Sandow was a visionary businessman, as well. He worked closely with his brothers Max and Jules, themselves wrestling managers and promoters, to develop a regular troupe of wrestlers who worked in each other’s interests to provide an entertaining show. Sandow, along with Lewis and wrestler Joe “Toots” Mondt, are frequently referred to as wrestling’s “Gold Dust Trio,” a name that originated in writer Marcus Griffin’s 1937 book Fall Guys: The Barnums of Bounce. In the book, Griffin credits the group with speeding up matches and developing a more dynamic in-ring style, creating a style Griffin dubbed “Slam Bang Western Style Wrestling.” While the book, which was based largely on input from Mondt, unquestionably overstates the group’s influence, Griffin’s exaggerations were based in some truth.

In 1925, Sandow also famously created wrestling’s first manufactured star when he took former college football standout Wayne Munn and turned him, almost overnight, into a heavyweight champion. Munn had been selected by Sandow simply because of his appeal to fans in the Midwest. Sandow hoped that a rivalry between Lewis and Munn would result in enough interest from fans to stage a match that would have been the largest gate in wrestling history to that point. The plan famously backfired when one of Sandow’s disgruntled wrestlers, Stanislaus Zbyszko, humiliated Munn during a match in Philadelphia.

Sandow’s most significant contribution, though, is his part in creating what can be thought of as wrestling’s state of fantasy. In it, there’s a quid pro quo between the performers and the audience where a fan’s discernment is exchanged for the kind of thrills that truly competitive sports are unable to reliably generate. Sandow, like William Brady, carried a match’s storyline out of the arena and into the press. He plainly understood that pro wrestling’s best chance for survival in a shifting sports landscape was as a circus-like spectacle that mixed athletics with an almost meta-type of surrealism.

One of Sandow’s favorite tactics for attracting press was to flatly contradict a match’s results if the outcome was not in his and Lewis’ favor. Sandow would stake claims for Lewis to championships he’d never won, or come up with ways to explain away losses based on technicalities that negated the outcome. Without instant replay, or the ability for fans to get a close-up view of the action without a ringside seat, who could argue with him about the minute details of what took place in a match? And it all made for incredible newspaper copy, anyway, so sportswriters were happy to work with him. Sandow pulled this trick over and over. Like Brady before him, he was a master of manipulating the reporting of events to fit it into the stories he was looking to tell to fans.

Sandow and Lewis ended their partnership in 1932 for reasons that remain unclear. “I have no idea why Lewis took up with another promoter,” Sandow later told journalist Ralph Friedman. “There are some things that happened that I can’t talk about. That’s when the racket outfit stepped into the picture.” Sandow would stay active in wrestling into the 1950s, before retiring to a small rancher off of Main Street in Portland, Oregon, in 1966. Even nearing his mid-80s, he was busily coming up with new business ideas. “Wish you would call me on the phone some time,” he wrote to a fellow promoter in 1966. “I have a great idea for something sensational.”

Sandow died on September 15, 1972, just a few days after celebrating his 88th birthday. He was survived by his second wife, Violet, and son Billy II. Who else, besides Mucken and Friedman, he spoke with about writing his memoir is unknown. What remains of his archive is a remarkable look into his career. That the family has managed to preserve his work for as long as they have is a testament to the affection they clearly continue to feel for him.

What also remains unknown is whether Sandow left behind more when he passed away. Both Mark Hewitt and I returned from our trip to South Carolina with the impression that he did. References in the articles published towards the end of his life hint at a larger collection of papers. It’s odd, as well, that a man so interested in being part of a book would not have maintained a journal or even made notes for later use. If he did produce writing which he hoped to use as the basis for his memoirs, it has never surfaced.

The existing papers have been seen by only a tiny handful of researchers. It’s a fascinating collection, and includes rare photographs of wrestlers Frank Gotch, Everett Marshall, and Gus Sonnenberg, promoter Jack Curley, and boxers Jess Willard and Jack Dempsey. A hand-written ledger from 1937 tracks boxer Joe Louis’ day-to-day earnings on an early tour that Louis undertook with Sandow. An undated holiday postcard features pictures of Ed Lewis, Billy Sandow, and Joe Mondt and was almost certainly sent out by the group to business associates. It is, perhaps, the only photographic evidence of the group’s business relationship.

Sandow also held onto copies of several of his training manuals on physical fitness and combat. Sandow published books on in-fighting aimed at soldiers, and on self-defense, aimed for the general public. The books are filled with photos and detailed instructions for dozens of holds. “The system …” Sandow explained, “is a simple and practical way of rendering helpless an opponent in the least possible time.” He also developed what he referred to as his “Kinetic Stress System,” a collection of books and workout equipment that he sold nation-wide that promised “sinewy strength,” and ultimately, to “create a new man out of you.”

The physical history of pro wrestling is hard to track down. Without a long-standing hall of fame endowed with enough resources to collect and preserve the physical remnants of wrestling’s past — the show posters, programs, and handbills; the ring wear and assorted championship belts; the business records, contracts, and accounting ledgers — much of wrestling’s tangible history is lost. To ensure that Sandow’s papers are preserved, the family donated them to the library of the University of Notre Dame at the end of 2019. The library already maintains the Jack Pfefer collection, the largest collection on professional wrestling held at an academic institution, and Sandow’s material will fit easily in along with Pfefer’s. “We are thrilled to acquire the Billy Sandow papers,” said Natasha Lyandres, Head of Rare Books and Special Collections at Notre Dame’s Hesburgh Libraries. “They represent an indispensable resource for researches and a hugely important addition to our outstanding sports collections.”

Billy Sandow was one of the men most responsible for modernizing professional wrestling during the crucial decades of the 1910s and ’20s. He made wrestling into something both more accessible yet mysterious and clouded, at the same time. Although Sandow’s papers will one day be more openly available to researchers, the man who collected them and held onto them through the vagaries of a 60-year career in sports, remains aggravatingly unknowable. Like all of his fellow promoters, he left behind almost no documents that hint at his inner life. We’re left only to speculate at his intention, to guess at how he understood and exerted influence over events around him.

Jon Langmead writes about pro wresting, music, film, and books on an increasingly infrequent basis at a few places around the internet. He’s a big Barry Windham guy.