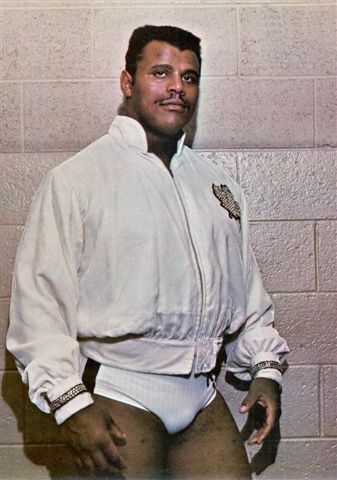

The Cauliflower Alley Club broke the news that “Soulman” Rocky Johnson, who was a huge wrestling star before he ever became known as the father of Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson, has died. He was 75.

The WWE reported the news as well. Details are still coming in. He had been in hospital.

Rocky Johnson. Photo by Dave Drason Burzynski

Johnson had a home in Florida and another in Missouri, where he lived with his spouse, Sheila. In the fall of 2019, his autobiography, Soulman: The Rocky Johnson Story, written with Scott Teal, was published by ECW Press.

Though he was born Wayde Bowles on August 24, 1944, in Amherst, Nova Scotia, when he was a teenager, he moved to Toronto where the wrestling (and boxing) bug caught him. He was actually at the NWA World title change at Maple Leaf Gardens in 1963 when Lou Thesz toppled Buddy Rogers.

Working out at the Trinity Community Centre in Toronto’s west end, he would come in contact with the wrestlers, and was soon dispatched to Jack Wentworth’s gym in Hamilton to learn a new trade — by day, he drove a forklift.

Johnson would debut in 1966, having just trained six weeks and weighing 217 pounds. “I taught him the business very quickly, with no horseshit,” said Hamilton’s Murray Cummings in The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: Heroes & Icons. “I showed him the moves, I showed him how the takedowns work, and everything. You showed him once and he had it.”

Turning pro was a politically expedient decision; Toronto’s top dog, Whipper Billy Watson, was campaigned for a federal government seat.

“He was looking to get the black vote, so he called Jack Wentworth and said, ‘Do you have any black guys there?’ He said, ‘I’ve got one. He’s young. Pretty good body, pretty good athlete.’ But naturally, no matches, right. So they put me on CFTO-TV, remember that? Channel 9. I worked with Firpo Zbyszko in my very first TV match. When you don’t know nothing, you can’t go wrong, you can’t make no mistakes. We went a 1:40, Firpo jumped me, bam bam, and I could always throw a decent dropkick. He backdropped me, I landed on my feet, threw four dropkicks, sunset flip. I’ll never forget this, and I’ll tell you why later, sunset flip, one, two, three. Nervous, couldn’t talk. He [Whipper] came out to talk for me. He said, ‘I’ve been training this guy for the last two years. He’s my protege’ — because he was trying to get the black vote. When I went home, my mother said, ‘But you just met him!'”

Though the Whip lost the election, Johnson excelled with the quick promotion. He was sent to the Dungeon in Calgary for further schooling. “That’s where Stu Hart stretched me,” said Johnson. “He broke a blood vessel in my eye.”

Toronto promoter Frank Tunney acted as a de facto godfather to him, advising him on his next career steps and talking him out of trips to the U.S. where he would have been eaten up and tossed aside. Instead, in Vancouver, he was given the chance as Don Leo Jonathan’s tag team partner.

“He had a lot of potential. He was just a young guy then. The only thing that was holding him back was his size. But later, he bulked up, muscled up, and looked pretty damn good after a while,” said the Mormon Giant.

“The Soulman” acknowledged that he was an anomaly. “They never had black wrestlers in Canada. There was a bunch of diamonds, and I was that black diamond in the middle. That’s the only way I could put it.” His upbringing in Canada meant that, unlike a lot of his peers in the U.S., he had never experienced outright racism and stood his ground when confronted by any prejudice.

“I never let it happen. They tried it in the south, but I stopped it,” he said, mentioning Nashville promoter Nick Gulas specifically. “My name is Rocky, not ‘Boy.'” Johnson’s title wins in places like Texas and Georgia actually broke the color barrier.

The trademark shuffling of his feet and his high dropkicks came early in his career.

It turns out that some of his early opponents, often long-in-the-tooth veterans like Fred Atkins or Joe Christie, couldn’t do the up-and-down moves that were required; therefore there was a need to fill time.

“I started dropkicking, and they were taking their time in getting up for it,” recalled Johnson. “I just started doing those little shuffles and all of a sudden people were going nuts. That’s all it took.”

Other than actual boxers turned wrestlers, such as Primo Carnera or Scott LeDoux, no grappler took the sweet science further into the ring than Johnson, who filmed vignettes with Muhammad Ali and George Foreman, among others, over the years. He had “boxing matches” with everyone from Jerry Lawler to Roger Kirby to Jim Dillon, and actually had a boxing license in Ontario while was starting to wrestle.

Getting to California in late 1969 was the key to his success, Johnson said. “I had already learned to wrestle, but I didn’t have the psychology until I went to San Francisco. You can teach a six-year-old kid a headlock, but you can’t teach him psychology.”

Having gotten his name out there, Johnson dropkicked across the continent for the next decade. According to Dave Meltzer of the Wrestling Observer, Johnson doesn’t get his due because he did travel so much. When pitching Johnson as a candidate for the newsletter’s hall of fame, Meltzer wrote: “Headliner and champion in nearly every territory he worked from the late ’60s into the early ’80s, particularly big in the ’70s when he had incredible agility and speed. In particular, is the best wrestler of the past 40 years when it comes to doing a dropkick series, and that’s considering he was a 255 pound powerlifter type with a boxing background. One of the business’ top athletes of the ’70s with a career record that is far more impressive than most realize.”

Johnson held titles everywhere he went, but the one that most cite as his crowning glory was the WWF World tag team titles in 1983, alongside Tony Atlas. The irony is that Atlas and Johnson didn’t get along and rarely actually worked together outside of TV tapings. “They couldn’t put us together because I wanted to smack him in the mouth every time I saw him,” Atlas said in the Shooting With the Legends newsletter.

For a time in the Mid-Atlantic territory, he wore a partial mask and was called Sweet Ebony Diamond, though it was obvious it was him.

Yet today, Johnson is known mostly as The Rock’s dad. It seems every contemporary has stories of young Dwayne — “Dewey” — hanging out backstage. But Dwayne wasn’t the first family member into the business. Rocky’s brother, Jay, broke into the business in 1978 in Toronto. In Hawaii in the early ’80s, the Johnsons, Ricky and Rocky, were a hot team, where Rocky was promoting with his inlaws, Peter and Lia Maivia, having married their daughter, Ata.

The Soulman’s career ended in 1987, but always in superb shape, he came back for a few matches on the indy scene in 1993, 1994 and 2002. In 2000, Johnson was the physical fitness and recreation coordinator for the South Florida town of Davie, working with the city’s Police Athletic League, and conducting pro wrestling fundraisers. In 2003, he was hired by WWE to help develop young talent; after all, his first trainee, The Rock, did okay. Brock Lesnar, Orlando Jordan and Sylvain Grenier all went through his finishing school. Another interest is draft horses, which he raised on a ranch in Missouri with his third wife, Sheila. At its WrestleMania extravaganza in 2008, WWE inducted Rocky Johnson into its Hall of Fame, with his son doing the honors.

Johnson had only recently been named to the Board of Directors for the newly-established International Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame.

The Cauliflower Alley Club broke the news on January 15; its president, Brian Blair, has been a close friend of Johnson’s for many years. His passing has been covered by many mainstream publications, including People magazine, CBC, and CBS.

Rocky Johnson is survived his three children: Curtis, Wanda and Dwayne.

— with files from Steven Johnson

RELATED LINK