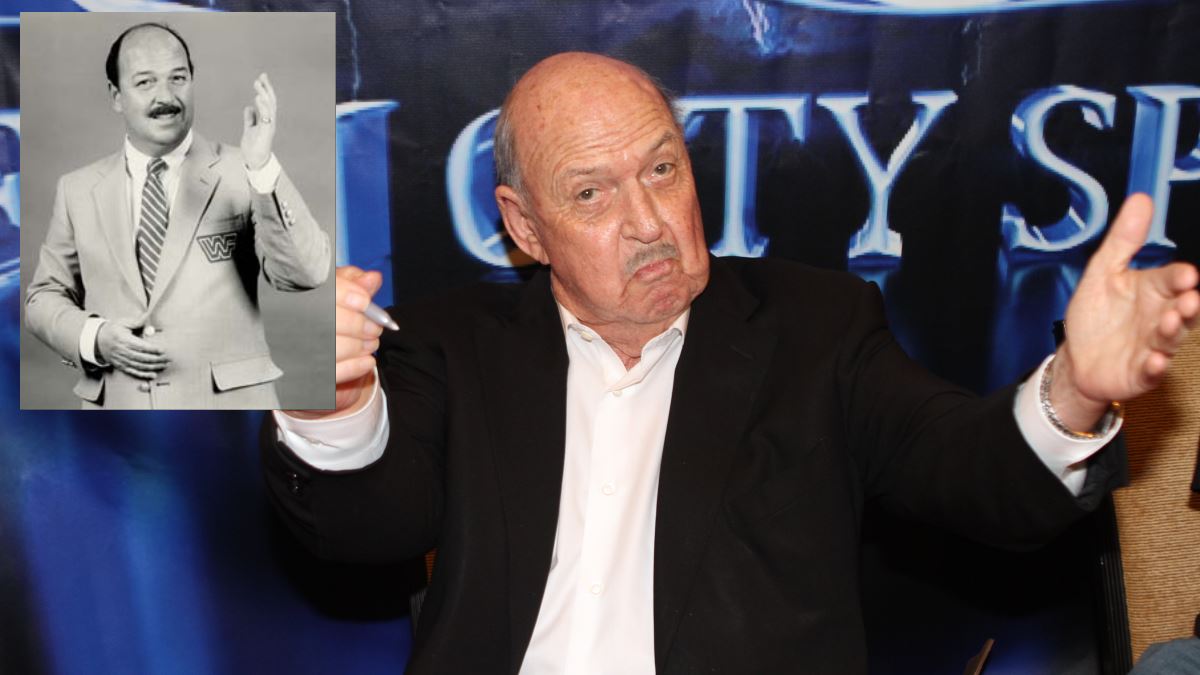

Long before achieving worldwide fame as the key interviewer and event pitchman for the World Wrestling Federation and later World Wrestling Entertainment, the first country outside the USA to experience the rapier-like wit and high-energy commentary of Gene Okerlund was Canada. Specifically, the northern part of American Wrestling Association territory with a telecast out of Winnipeg.

The AWA viewers here (and in Brandon, Dauphin, and other rabbit-ear towns) were rabid Gene Okerlund fans, although as his career evolved, they didn’t get to see the payoff of his build of Hulk Hogan in the 1980s since our market didn’t have any WWF programming on TV when the infamous tag match as Hogan’s partner went down in August 1984.

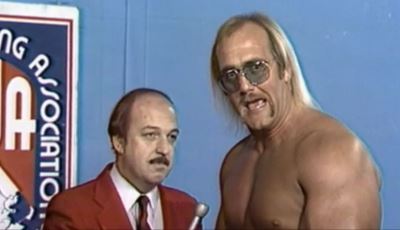

Gene Okerlund and Hulk Hogan during their AWA days.

Handling interviews of top AWA stars between bouts, Gene was stepping into the role of grandfatherly Marty O’Neill, an established sportscaster who played baseball with Casey Stengel in his youth. Low-key, Marty’s pitch lines included some adopted by Okerlund including “Run, don’t walk, to get your tickets.”

As reported by KARE 11 TV in Minneapolis, “Gene Okerlund was born in Sisseton, SD, but moved to the Twin Cities in 1967 where he worked in radio for a number of years, before he came to WTCN Channel 11 as a salesman.”

He had been lead singer for a rock-and-roll band in his youth and was not a shy person. So it seemed a natural progression when (as KARE explained), “He was asked to sub for then AWA ring announcer Marty O’Neill during a union strike in the early ’70s and it quickly became apparent he was a natural.”

That long-forgotten aspect of his on-camera debut was not mentioned by any other source I could find after his passing, but it seemingly never worked against him because he was already working for the TV station in a non-union position and wasn’t technically crossing a picket line.

However KARE did report was another factoid about his debut that I had never seen before: “I went up to Gene’s cabin up north and spent a weekend with him doing mock interviews. And it worked out. The rest is history. He was the greatest, bar-none,” said Al De Rusha, a fellow AWA announcer and referee who helped elevate Mean Gene within the company.

One hopes perennial AWA champion and owner Verne Gagne gave De Rusha a bonus for it.

Around 1976, Gene became the full-time interviewer on the Channel 12 All Star Wrestling (known that way by fans to distinguish it from the identically named, syndicated, Vancouver-based All Star Wrestling on Channel 5 featuring Gene Kiniski). Pitching the upcoming Winnipeg Arena events like a full-court press, fans here quickly picked up on his articulate, higher energy and decidedly bombastic presentation. He was the face of the AWA in an era where Winnipeg drew more fans per capita than anywhere else in North America — eight recorded crowds over 8,000 in 1976, for instance — his build up for interviews prefaced with praise for the local promoter: “Fans, a tip of the hat to promoter Al Tomko, putting together yet another, all-star card.” Okerlund’s voice, full of authority and enthusiasm, compelled viewers to stay tuned.

Tomko began taping the Arena bouts to be dropped into the Minneapolis AWA tapes, to ensure required Canadian content rules were met. Thus began Okerlund’s additional role doing play-by-play on many of those cards, which allowed his dramatic flourishes to be appreciated in a different, long-form setting. There were times that AWA studio match voice Rodger Kent came up to do the play by play, but the difference was stark. He was excitable, but not exciting anymore. Gene was.

(It appears his first cross-Canada broadcast of his work was not on a WWF program, but rather when Tomko bought into the Vancouver promotion and used the tapes of Arena openers to build up undercard journeyman that were to be his new stars on the west coast. Only Gene Okerlund could make Dave Kochen vs Puppy Dog Peloquin sound like a main event match.)

As Okerlund praised the sportsmanlike efforts of the rising handsome High Flyers tag team (Gagne’s son Greg and Jumpin’ Jim Brunzell) from the previous card — “man oh man alive, talk about your action!” — he would sternly hold the sneering World Heavyweight Champion Nick Bockwinkel and his manager Bobby “The Brain” Heenan to account, springing surprise challengers and “Wally! Wally Karbo!” matchmaker stipulations on them and proclaim “we’re outta time!!” cutting off their protests of a conspiracy. The straight and punch lines reeled off with Heenan, The Crusher, and Baron Von Raschke were repeated on schoolyards and lunchrooms for years after.

He was uniquely talented at bringing on newcomers who were not yet at ease with the camera and giving them perfect set-ups to get used to talking about themselves and their opponents and get themselves over. His battle of wits with Jesse “The Body” Ventura resulted in Jesse coining the “Mean Gene” tag that stuck for almost 40 years.

The Golden Goose of the wrestling business became Hulk Hogan, and upon his rapid switch to the babyface side of the AWA cards in 1981 and rise to challenge Bockwinkel and the Heenan Family, and vanquish menaces like Mr. Saito and David Shultz, Okerlund pushed the huge muscleman to the moon and beyond. In this period he and Hogan were notorious for their post-Arena partying at the Polo Park Inn, taking over the stage with musical performances and plentiful cocktails. What a sight. Winnipeg fans lucky enough to squeeze in to the lounge gabbed for weeks afterwards about it, and they barely saw any of the antics.

Okerlund helped establish the “Incredible Hulk” as a true ticket-selling attraction aided, of course, by being a movie star from Rocky III. Vince McMahon recognized their act was the ticket to world-wide expansion and network and pay-per-view success. Acquiring the duo at the end of 1983 was the key moment in changing the wrestling industry from a regional to truly international enterprise. Heenan had already jumped ship as had Ventura, so many more moments of conflict and mirth were soon to be (re-)created among the four of them.

Okerlund was a staple of the morning Superstars TV show and annual Wrestlemania showcase for years after, and his venture into Ted Turner’s World Championship Wrestling brought WCW great credibility as it rose to a spirited ratings skirmish with WWE during the Monday Night Wars. In his later years he voiced features and segments for WWE Network and programs, evolving into basically, a grandfather like Marty O’Neill, but far more ribald.

So many WWF fans on his passing called him “the voice of their childhood,” but was in fact the soundtrack for wrestling fans in Winnipeg, Brandon, Dauphin and across Manitoba for eight years before those fans ever heard him. The entertaining style Gene Okerlund provided as a voice of information and authority was honed in the old territory era leading up to his New York breakthrough, and Winnipeg was the first market outside the USA to enjoy his showmanship.

RELATED LINK