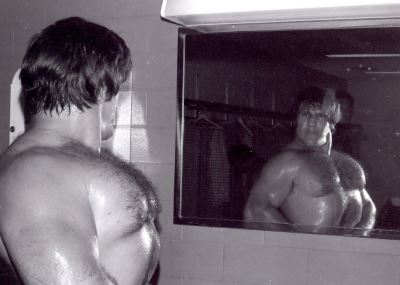

Bruno Sammartino poses in a mirror in Toronto. Photo by Roger Baker

Bruno Sammartino, one of the greatest wrestling champions of all time, has died. He was 82.

According to Pittsburgh TV station KDKA, Sanmmartino passed away with his wife and children by his side. He died peacefully after battling health issues for the past several months.

Long-time friend Christopher Cruise posted on Facebook that Sammartino died on the morning of April 18 around 9 a.m.

“He had been hospitalized for almost two months and fought to live every day,” wrote Cruise. “His passing leaves us all shattered. His body had been affected greatly by pro wrestling but he did not complain. Pro wrestling gave him much but cost him at least ten years of life. I hope we understand the price he paid for the sport.

If Sammartino had never taken a fall, his life story still be would as compelling as anything Hollywood could fabricate.

Born in October 6, 1935 in Pizzoferrato, Italy, in the central part of the country, he fled his village in 1943 when German SS troops overran the area during World War II. His father Alfonso had emigrated to Pittsburgh for work before the war, and was stuck there when Sammartino, nine, escaped with mother Emilia, a sister, and a brother to a mountainous area called Valla Rocca for fourteen months. Sometimes, they ate nothing but snow for days on end. Emilia snuck into the village to snatch food when Nazi guards were not looking, and once was shot in the shoulder.

Returning to the mountain in October 2010 as part of a documentary, Sammartino reflected: “I’m overwhelmed by it because I put myself in her place and wonder if I was man enough if I could have ever done it.”

Cruise was with him as he revisited his past, and said those horrific experiences unquestionably forged Sammartino’s sense of right and wrong. “It’s a story of a little boy who was put up against a wall, and the Nazis were ready to fire and shoot him and his family. If he just came to America and became a carpenter and a family man, it’s an extraordinary story,” Cruise said.

After the war, Sammartino was so sickly that it took three years before medical authorities would clear him to travel and reunite with his dad in America. When he did, around 1950, he was a poor, skinny, 83-pound weakling, bullied at school and barely comprehending English. A friend helped him get a membership at YHCA, and lifting weights and wrestling became child’s play compared with living a life of fear in Italy.

“I can tell you that I became addicted almost immediately to physical fitness. They had a wrestling program, amateur wrestling, and they had weight training,” he said. “My gym teacher was friends with a guy named Rex Perry, who was a wrestling coach at the University of Pittsburgh. Perry wanted to know if I’d be interested in going up there and working out with the big wrestlers. I started going on that program six days a week, religiously, no matter what work I did, like summertime when I was working construction.” He went from weighing 130 pounds to 270, and bench pressing more than twice that amount. Sports announcer Bob Prince spotted him, referred him to Pittsburgh promoter Rudy Miller, who in turn sent him to see Vincent J. McMahon in Washington, D.C.

He debuted in the fall of 1959 and made his first appearance in Madison Square Garden, which he’d make the Mecca of wrestling, on January 2, 1960, beating Bull Curry in five minutes.

Jackie Fargo was wrestling there at the time and in The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: Heroes & Icons, remembered how protective promoters were of a young Sammartino, wanting to build him as a superhuman force. “I worked with him when he first started in New York. Gawd, was he green! They told him, they said, ‘Don’t go off of your feet. Don’t go down for nobody.’ Well, my manager Jack Pfefer, he told him, ‘Jay-kee will dropkick you and you will go down two, three times.’ Oh, he did, and boy, they raised hell about that. They said, ‘We told you not to go down.’ He said, ‘Well, Fargo dropkicked me and Pfefer told me to go down.’ ” Sammartino was quickly on the top of the cards and just as quickly off them, winding up on promoters’ “don’t hire” list in 1962, after a rift with McMahon and a missed booking he didn’t know about. With some help from Yukon Eric, he ended up with promoter Frank Tunney in Toronto, where his appeal to a large Italian population led to a boom in business before he returned to New York. “He told me he got a call from Vince McMahon and Vince wanted to bring him in, and Bruno was doing well for himself in Toronto, and then Vince told him, ‘I want to make you my next world champion,’ ” said Pete Sanchez.

Sammartino won’t speak ill of Rogers, but there was bad blood between the two. “Look, Buddy’s gone now. I will never tell you that he wasn’t great because that wouldn’t be true. But he and I, I don’t know how it happens in life, I don’t know, Buddy and I never liked each other from the first time we ever met,” he said.

The Rogers-Sammartino bout on May 17, 1963 might be the most famous forty-eight seconds in wrestling, but less known is the fact that Rogers was hardly out of his hair. In early 1964, “Wild Red” Berry brought Bill Watts to the WWWF, and the big Oklahoman quickly rose to become the number two hero behind Sammartino, and close friends with the champ. Behind the scenes, though, Berry had been spiriting Watts away for visits to Rogers’ house. “I was in awe of who he was; he had a lot of money and he had a lot of investments and he had a lot of swagger. But I didn’t understand what he would be setting me up for,” Watts said.

Things became clearer when, in a confidential meeting in his Washington, D.C., office, McMahon told Watts he’d patched up his disputes with Rogers and wanted the Cowboy to visit him to discuss a big money deal. As it turned out, Rogers planned to manage Watts in a heel turn against Sammartino. “He was going to come out of retirement and I was going to become his discovery, his protégé,” said Watts, who felt compelled to tell Sammartino, though he’d been admonished to keep matters hush-hush. “Bruno comes back and says, ‘First of all, Bill, I know Buddy Rogers like a book. You don’t. He’ll come out of retirement and he’ll manage you but he’ll end up working in on the deal and he’ll drop you. The whole deal is for him to get the championship back. I won’t work with him.’ ” In the end, Watts pitched the bad guy switch without Rogers and the result was box office gold for months.

Bruno Sammartino in his heyday.

For most of the 1960s, the WWWF formula was simple. Monstrous bad guy, meet Bruno. Have a three-match series, usually with a count-out, disqualification, or bloodletting thrown in, and then be vanquished. Hans Mortier, Professor Toru Tanaka, Killer Kowalski, Crusher Verdu … it was a simple but effective script, and it played off the schisms society was experiencing at the same time, Cruise said. “In the ’60s and into the ’70s, it seemed like the bad guys were ascendant, the Russians and the remnants of World War II. And especially in the ’60s, where the world went from black and white to gray, Bruno represented the triumph of good over evil. I think that was part of his attraction.”

Could the Sammartino formula have worked elsewhere? Sure, albeit to different degrees. St. Louis promoter Sam Muchnick, the head of the NWA, was not known to pal around with wrestlers, but he liked Sammartino, used him as a special attraction, and publicly took Bruno and wife Carol to the well-known Ruggeri’s restaurant. Sammartino went to an hour draw in St. Louis with NWA champ Harley Race in front of 10,043 in June 1973, though a return as WWWF champion in 1975 and 1976 drew crowds of less than 5,000 against Stan Stasiak and Dick Murdoch.

“Even though he was not the prototypical NWA champion, he could have been NWA champion for Sam because what he didn’t bring maybe in some certain refined wrestling skills, he brought in his power, skills, and class. He could bring respect for you,” said Larry Matysik, Muchnick’s right-hand man, who also booked and called the matches in St. Louis.

Sammartino’s strength and conditioning might have saved him from a life in a wheelchair. Stan Hansen broke his neck on April 26, 1976, not with a clothesline, as promotional material contends, but with a missed scoop slam. “That’s what broke my neck, not the lariat, and I did break my neck. In fact, my doctors told me that I came within a millimeter of being paralyzed from the neck down,” Sammartino said. His comeback was part of the closed circuit Antonio Inoki-Muhammad Ali telecast and drew about 32,000 fans to Shea Stadium. Hansen was probably fortunate to avoid the wrong kind of retribution. “Bruno said some of the ‘connected’ people he knew told him, ‘Let me know if you want me to take care of this,’ ” Hansen said in 2011 while promoting his autobiography. “Thank God Bruno said, ‘No. That’s all right, because I’m going to get him.’ ”

Sammartino’s first WWWF title reign was singular, lasting a record seven years, eight months and a day. When the WWE title was reformulated in 2002, in the same amount of time, it had thirty-six champions. He came back in December 1973 for a second reign of three years, four months, and twenty days before falling to Billy Graham on April 30, 1977, in Baltimore, Maryland. Put them together and it’d be among the top ten longest-running shows on Broadway. Fifteen years after the Watts heel switch, Sammartino was in semi-retirement as an announcer when Zbyszko, who grew up cheering him in Pittsburgh, played a similar card, bloodying his mentor’s head with a chair during a supposedly scientific workout on TV. More than 36,000 fans turned to Shea Stadium in August 1980 to watch them settle their score in a cage match, the largest crowd in New York wrestling to that point. “Because of what I had learned from Bruno, I realized that, number one, the fans wanted to see Bruno back. I was a big Bruno fan. I wanted to see him back,” Zbyszko said. “He was great to work with because there was so much emotion. You didn’t have to really do a lot to blow the ceiling off of the arena. If Bruno would give you a couple of arm drags, the people’d go nuts. If Bruno died, people died.”

Bruno Sammartino in April 2012. Photo by Andrea Kellaway

Sammartino by and large retired after the Zbyszko angle, but Vincent K. McMahon wooed him in the ring again in 1984 after he took over the company from his dad. It was a decision Sammartino lived to regret. He thought he was going to be able to win a push for his son, David, but that never materialized. He and David have been estranged for years and Sammartino said he’s tried to put his last comeback out of his mind. “Those were very unhappy times. I didn’t go in there with a great feeling like previous matches because this was after I had retired, circumstances were not the same, and I have no good memories of any of those matches,” he said. He’s been a critic of McMahon’s WWE, and vocal about steroids and drugs; he’s a first rank hall of famer everywhere except the WWE. In fact, George Steele said the Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame in Amsterdam, N.Y., was designed in part to honor Sammartino, but he wouldn’t come near it because he sensed a possible McMahon connection. “Bruno is hard headed. Right at the last minute, after we started our first induction―Vince did it, or somebody did―they got word to Bruno we were using Vince McMahon’s money, which was an absolute lie. And that’s why he rejected it,” said Steele, instrumental in the founding of the PWHF. Wooed by Triple H, Sammartino eventually relented and was inducted into the WWE Hall of Fame in 2013.

Sammartino underwent successful heart surgery in 2011; naturally, he was back on his feet and lifting weights within a few weeks. He has remained an icon in wrestling and in Pittsburgh, where he received a lifetime achievement award in 2010 from the Dapper Dan organization, the city’s premier sporting organization. It was a final sign that he was respected by the mainstream, even if his sport wasn’t. As he told his hometown Pittsburgh Post-Gazette newspaper: “I never expected anything like this. Wrestling isn’t looked upon like the other sports of football, baseball, basketball and hockey. I’m deeply honored.”

Sammartino is survived by his wife Carol and his sons, David, Danny and Darryl. Funeral arrangements are not known at this time.

RELATED LINK

Greg Oliver and Steven Johnson both interviewed Bruno Sammartino many times. A class act. He’s the #3 all-time hero in their book The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: Heroes & Icons (with Mike Mooneyham). Greg can be emailed at goliver845@gmail.com, and you can follow him on Twitter @gregmep.