Nature Boy: Disappointing ESPN hagiography falls flat

“When the legend becomes fact, print the legend,” is a line from The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance.

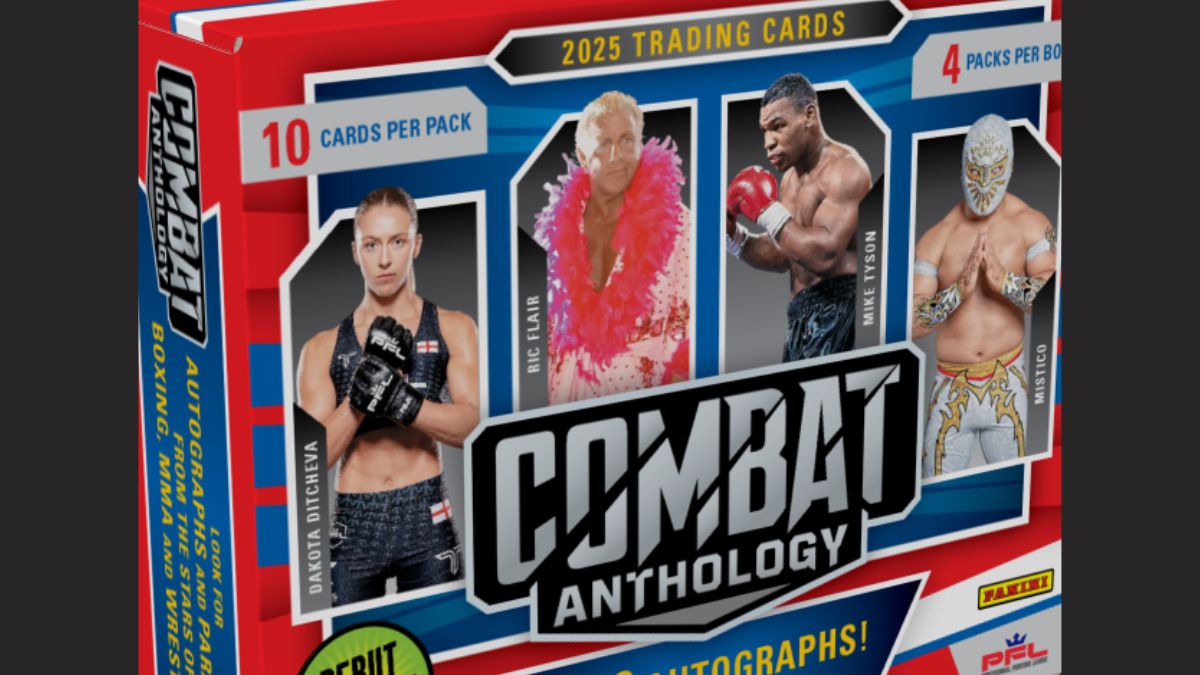

With a professional career that has spanned more than four decades, Ric Flair is certainly a worthy subject for ESPN’s 30 For 30 documentary treatment. Unfortunately, director Rory Karpf missed the mark with Nature Boy, serving up a 90-minute piece of myth-making that broke little new ground. There is a fascinating story there, but 30 For 30 didn’t tell it.

Admittedly, the 30 For 30 format was designed to tell the story of an athlete whose career might last 10 years, or the story of one memorable season or series. Encapsulating 40 years of “The Nature Boy” into 90 minutes (less with commercials) makes it impossible to go into deep detail. But the documentary suffered from a lack of historical context and unforgivable lack of fact-checking that more of a puff piece than the hard-hitting documentary that ESPN had been hyping for months.

Karpf lined up some very strong guests to offer up their stories of Flair’s wild behavior and excesses, including Sting, Jim Ross, and even Hulk Hogan, who was uncharacteristically humble, calling Flair was “10 times better” than Hogan ever was. A skeptical viewer might suspect Hogan was in full PR mode in an effort to make forget about those nasty racist comments he made a couple years back.

Many remarkable incidents from Flair’s life — including his relationship with his adopted parents, the airplane crash that nearly cost him not just his career but his life, and his crippling depression later in his career — were glossed over, while they were deeply explored in Flair’s 2004 autobiography, To Be The Man.

Director Karpf came across as a Flair fan-boy who was more interested in living vicariously through the “Nature Boy” gimmick, instead of a journalist probing for the true story of the man himself. Flair’s utterly ridiculous claims that he slept with 10,000 women and drank 17 drinks a day — every day — for more than 30 years went by completely unchecked. While his in-ring rivalries with Dusty Rhodes, Sting, and Hogan received cursory treatment, the scope of Flair’s achievements in professional wrestling went largely untouched. If, as Flair explains, wrestling is “choreographed,” then what made Flair stand out above his peers? A narrative voice explaining Flair’s accomplishments and role as NWA champion would have done more to flesh out the story and provided context.

Certainly, a 30 For 30 piece on a NFL or NHL star would have included statistical information and team information; in other words, what made them great in their field. Those statistics may not apply to “sports entertainment,” but some acknowledgment of Flair’s achievements was warranted. When asked by Karpf on what made a wrestler great, Flair replied “technique” and “agility.” It was a vague and unsatisfying response that went without follow-up or explanation.

After all, Flair admitted he virtually stole his look and nickname from Buddy Rogers and his “whooo” from Jerry Lee Lewis; what made a guy using other people’s looks and style excel to the level he did? The documentary never even attempts to answer the question.

There was no mention of Flair’s role as a booker with Jim Crockett Promotions, a fact that would have shown him as a businessman and more than simply “The Nature Boy.” His other business ventures, and his financial ruin that was superbly covered by Grantland, went completely untouched.

The real meat-and-potatoes of the piece was the third reel, focusing on Flair’s relationship (or lack thereof) with his family. Flair talks about how he was unable to transition from “The Nature Boy” to Richard Fliehr, Family Man. “I always wanted to be The Man. I could never live being just A man,” Flair said. As for being absent from his family from 1972 to 1999, Flair lamely responded, “Once you’re World champion, what else is there for you? What else are you going to do?”

Consider that for one moment: Flair was scripted to be champion in a “choreographed” form of performance art. That role, and the “10 pounds of gold” that went with it, was more important to him than his own family. This is a delusional way of thinking, but it was passed off as “Ric being Ric.”

The best, most genuine, part of the documentary is after the hagiographic animations and bar stories when Flair speaks about the overdose death of his son, Reid. Flair says he regrets being a “best friend” to his son instead of being a father. It’s one of the very few redemptive moments in a sad story that’s masquerading as a celebration.

Nature Boy captured the glitz, the glamour, and the whooos, but it lacked the warts-and-all honesty needed to truly go behind the curtain and show us the man behind the gimmick.