As good as “Pretty Boy” Larry Sharpe was as a wrestler, and especially as a trainer, he was an even better storyteller. There’s an art to it, a build up, full of small, memorable details, and a payoff. Though his own story came to an end with his passing on Monday, his tales can live on.

The last time I talked to Larry Sharpe on the record came after the death of northeast referee Dick Woehrle in March 2012. Larry launched into a story about a sold show he once ran in conjunction with Pathmark supermarkets that included a lot of corporate bigwigs. Since it was a bought show, at the conclusion of the bouts, “Mr. Pathmark” James Karen, who had done many ads for the company, came out to create a memorable, victorious moment for the company and went over in the ring.

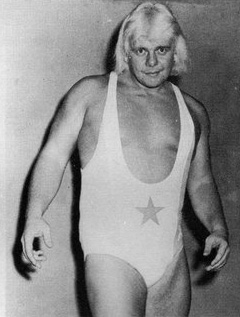

“Pretty Boy” Larry Sharpe

That’s a nice set-up, but not the kicker.

Backstage, Woerhle starts chatting with an older African-American.

“I know you. I think I used to train you for boxing in Scranton. I never forget a face,” said Woerhle.

“No, I never boxed before. You must have me mixed up with somebody else,” was the reply.

Woerhle keeps on keeping on, insisting he knew the man from boxing. The man replies, “Well, who are you?”

“Who am I? I’m Dick Woerhle! Who are you?”

“I’m Willie Mays.”

In his high-pitched, nasally voice, Sharpe starts laughing at the punchline, enjoying the memory of his friend Dick Woerhle. “He used to get so pissed off when I’d tell that story!”

Larry Weil was born June 26, 1950 in Paulsboro, New Jersey, and died March 10, 2017, not far away in Woodbury, in hospice care after battling liver cancer. In between is a story of not-quite greatness as a pro wrestler, and unexpected stardom as a trainer of only one of his many successful students.

Professional wrestling was the first sport he ever got to see live, in 1957, when his father took him to the Camden [NJ] Convention Hall. He saw many of the stars of Capitol Wrestling of the time: “Nature Boy” Buddy Rogers, Bobo Brazil, The Fabulous Kangaroos. Also there was manager Wild Red Berry.

“In the middle of that card, I turned around to my father and said, ‘This is what I am going to do when I get big,'” Sharpe said in 2010, when inducting Berry into the Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame, then located in Amsterdam, NY. “He wished me luck. Later on that night, we were in the same diner as Red Berry. I went and approached him. I said, ‘What do I have to do to be a professional wrestler?’ He told me to get 10 years of amateur experience. As I did, he followed my career. He kept his word.”

Sharpe wrestled amateur in Grade 7 and 8, and then for four years at Paulsboro High School, going 13-1-1 in his senior year. Berry “brought Gorilla Monsoon to watch a junior wrestle in high school, which to me was pretty impressive. If it wasn’t for him telling me about amateur wrestling, I would never have known that there was wrestling that didn’t have ropes, because that’s all I knew up until that time.”

The amateur skills got Sharpe to Gloucester County College, where he was nationally ranked, and then to Trenton State on a scholarship. Graduating after two years, he got a letter from Berry telling Sharpe he’d be in town in a couple of weeks and he’d hear from him then. He didn’t.

A couple of months later, Sharpe heard from Monsoon, who told him that Berry had died a couple of days after sending that letter. With his own pull as a part owner in the WWWF, Monsoon offered Sharpe a chance to get into the business, and the newcomer learned the ropes under veteran Tony Altomare at Paserillo’s Quest Wrestling School in Orange, Connecticut. That was 1974.

Sharpe never left.

SWEET RIBS

Okay, time for another story. How about a bear?

For a period of time, Sharpe teamed with Ripper Collins, including a run together in Calgary’s Stampede Wrestling, and many of those stories are not clean enough to print here. But this one is.

Collins got involved behind the scenes in Hawaii with promoter Ed Francis, and he loved gimmicks. He convinced Francis to bring in George Allen’s wrestling bear. Ripper also liked the spotlight, even if he’d gotten older and wasn’t in the best of shape.

Sharpe and Don Muraco saw a chance for a memorable rib.

“The bear had a muzzle on it and it was de-clawed. On the way to the ring, me and Muraco — you know what a ketchup squeeze bottle is like? We squeezed honey on Ripper’s ass and he didn’t know it. So he gets to the ring and the *&%$ bear takes after Ripper, trying to lick his ass, and he doesn’t know why. Ripper’s running around in circle. You know the bear’s tongue, when comes out, it looks like a snake! George can’t control it; the bear wants the honey and it’s all over Ripper’s tights. Ripper comes back in the locker room, and he goes, ‘Larry Sharpe and Don Muraco can wrestle the bear from now on!’ It was hysterical.”

Needless to say, Sharpe is laughing hysterically while recounting this story. “I see that like it happened yesterday afternoon.”

Jokes and Sharpe went hand in hand, said Bill Howard, another journeyman like Sharpe who was respected and liked by his colleagues, even if they were never headliners. “Larry is something else when it comes to ribs, boy! He’s a funny guy,” said Howard. “He could wrestle, too. Nobody knew that.”

Phil Watson, the son of Canadian legend Whipper Billy Watson, dated Collins for a time, and got to know Sharpe’s sense of humour. They were in Pittsburgh, and Watson did the honours for Bruno Sammartino Jr. (later known as David Sammartino). “I made him look like a million bucks. I’m sitting there with Pretty Boy Larry Sharpe. Bruno [Sammartino Sr.] is sitting there at the bar. There’s this old man, he must have been 75 years old, came in, and sat down. He just looked like a real old mafioso,” recalled Watson. “Larry Sharpe says, ‘You know what I think I’m going to do?’ I said, ‘What’s that?’ He said, ‘I think I’m going to go up to that old man sitting there talking to Bruno. I’m going to smack him right across the face and say, “That’s from me, Phil Watson.”‘ I said, ‘*&%$ you, don’t you dare!’ Larry, he was a funny, funny guy.”

There aren’t many places that Sharpe didn’t wrestle, including Florida, the Carolinas for the Crocketts, in Texas for Fritz Von Erich, Stampede, Hawaii, Japan, the Pacific Northwest, and Puerto Rico.

EARLY DAYS OF TRAINING

Along the way, he found a knack for teaching the fundamentals of pro wrestling.

“Tony Atlas was the very first guy that I trained,” said Sharpe. “I was working in Charlotte and I had a solid amateur background … Tony was a Virginia state champion, and of course he was Mr. U.S.A. They wanted someone to teach how to work. Gene Anderson was the assistant booker, so Gene and I would meet him at the YMCA in Charlotte. It was kind of unfair, but most of the time, they would, not beat him up, ‘Okay, give me 500 push-ups, give me 500 sit-ups, or 500 squats, go job five miles, now you’re going to wrestle Larry, who hasn’t done a damn thing all morning.’ I wrestled him every day for probably two months.”

It was also an eye-opening experience for Sharpe as far as the money in the business, and how his own talents were appreciated. “The office obviously respected my wrestling ability to give me that job,” considered Sharpe. “But his first week in the business, I think he made $900, and I made $400. That really pissed me off.”

Another that fell under his influence was Kevin Von Erich, circa 1976

“I guess George Scott and Red Bastien, you know, all the bookers across the country — the territories were a great thing back in the day. Somehow they found out that I trained Tony Atlas. I really didn’t say a lot about it. Then Fritz said, ‘I’ve got a son that wants to break into the business. Do you mind working with him?’ I was with him every day, at the Sportatorium, and Paul Perschman came down occasionally — ‘Playboy’ Buddy Rose. The two of us worked with him.”

Naturally, Sharpe worked in Kevin’s debut match, a six-man tag team affair, where the rookie went over. “We did a 20-minute match, and of course, I had him beat me with the Claw, which made the old man happy. He was good. He wrestled barefoot. He did break my solar plexus; he gave me a bad monkey flip and it broke my collarbone. But stuff like that happens, that’s the way it was.”

Mae Young and Larry Sharpe at the Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame induction weekend in Amsterdam, NY, in May 2012. Photo by Andrea Kellaway

BEATING THE BEAR

Okay, time for another bear story. Same bear, different day.

They were in Molaki, Hawaii, with a packed house and everyone sweating, and it was Sharpe’s turn to wrestle the bear.

“When you wrestle the bear, you go back and give him a Hershey bar, you let him smell you so he gets used to the scent. … We went back, and must have given it six or seven two-liter bottles and about a pound of Hershey bars — a whole box of them, however many is in there. When the bear went out to the ring, it should have been hibernating somewhere. It’s in the heat in Molaki. I told them, ‘I’m going to beat the bear.'”

He conspired with special referee Tor Kamata to make sure that he’d count the pinfall properly.

“The bear has a couple of moves that it can actually execute. One of them is a flying mare, so if you go behind the bear, it reaches over its shoulders and flips you forward. So I get behind it, and when the bear reaches back, I grabbed its mane and yanked as hard as I could. It had so much *&%$ in its stomach, it just rolled back, I got it off balance. I threw myself on top of it, and before I was there, Kamata had come down to the ring and made the three count. The people went nuts — and I was the heel”

George Allen, whose livelihood was taking the bear from town to town protested that it wasn’t a pinfall and tried to get Sharpe back into the ring to no avail. “He was pissed off at me for the longest time,” laughed Sharpe.

THE MONSTER FACTORY

In 1983, his own career winding down, Sharpe teamed with former NWA and WWWF World champion “Nature Boy” Buddy Rogers to open a wrestling school. It was initially called Champion’s Choice, and then Buddy Rogers’s Wrestling School. Rogers wanted to teach his son the wrestling business, but that didn’t pan out, so Buddy moved to Florida and Sharpe took over the business and renamed it the Monster Factory.

In an interview with Deathvalleydriver.com, Sharpe continued the story. “That name caught on with the media. You know, NBC, ABC, CBS, they all liked that name. You know, once you’re on one, then it snowballs. Then it’s Sports Illustrated, and then when Sports Illustrated had it in, People magazine saw it. When People magazine had it in, Rolling Stone saw it. When Rolling Stone had it in, you know, it snowballed like that for me. A Current Affair came in and did something about eight months ago. They ran it on television, and there was virtually no response at all. They re-ran it two months ago on a Friday night, and I had 28 phone calls on my machine when I went in Monday. I guess it’s just the audience, what you’re on against at that particular time.”

It’s not an exaggeration to say that the Monster Factory churned out some of wrestling’s top names, from Bam Bam Bigelow, who got so much publicity, to Chris Candido, Tatanka, Balls Mahoney, The Headbangers, D’Lo Brown, and The Pitbulls

“Larry’s known around the world as the top trainer in professional wrestling,” said Dennis Coralluzzo in a 1989 story about the school. Coralluzzo and Sharpe were also partners in countless wrestling shows around the northeast, under the Excalibur Promotions. They pushed the idea of fundraisers for nonprofit organizations, or corporate shows for grocery stores where famous baseball players hang out.

Scott “Bam Bam” Bigelow and Larry Sharpe.

Domino Cliff Compton was one of Sharp’s students. “In 1998 he took me in @4MonsterFactory. He was the nicest and craziest coach I ever had,” he wrote Monday on his Twitter account.

Even in 2011, having mostly turned over the training reins to other people, and eventually selling the Monster Factory completely, Sharpe dreamed of finding the next star, like a Bigelow, that maybe he could manage to the top again.

“The thing about the Monster Factory is that I can always go get another guy. It’s like the military, the Chinese Army, there’s plenty more where that came from,” he said, telling of a monster he had been training that he hoped to take to Puerto Rico, which was probably the scene of his greatest moments.

FLYING IN PUERTO RICO

The style of pro wrestling in Puerto Rico is different than the continental United States, and the fans are ultra passionate. And the promoters? “It was not a safe place to work, and it was scary at times, not only from the people, but from the office itself. It was like working for Al Capone.”

“You didn’t have to be a brilliant worker to get over down there. Jack Evans and myself went down. He was Panamanian and Hungarian, but we said that he was Puerto Rican, because he could speak Spanish,” Sharpe said.

Debuting in 1970, Evans (Eric Verbel) had transformed from being Jean Madrid to becoming Sharpe’s partner in The Hollywood Blonds. “We had long, blond hair, we had the beautiful gowns and robes and all that kind of stuff,” recalled Evans.

Before their TV debut in Puerto Rico in 1977, Evans and Sharpe piledrove Victor Jovica, and he wore a neckbrace for six weeks. News got around so that when they made their TV appearance, it had impact.

“Jack was not a very good speaker, so he let me do most of the talking,” said Sharpe. “We had set up a promo for him, and basically what he said was, ‘Larry Sharpe’s father owns a huge tomato and asparagus farm in New Jersey. My father worked for him, and I worked for him, and my mother is a whore who lives on the street in a ’57 Chevy in New York City. I’m embarrassed to be Puerto Rican, and if it wasn’t for Larry taking me under his wing and getting me off the farm, I’d still be a no-good Puerto Rican. That’s why I dyed my hair blond; I’d rather be his brother than a Puerto Rican’s brother. As I speak Spanish, it basically tastes like *&%$ coming out of my mouth, so after this interview, I’m never going to speak it again.’ Well, you say something like that, and you’re over.

“Six weeks later, when Jovica got the neckbrace off — and he did wear it for six weeks, everywhere he went. We sold out Roberto Clemente Stadium and Harim Bikram Stadium. We did tremendous business. Listen, Jack is a good worker, and I’d like to think of myself as a good worker, but with promos like that are just as important as your work.”

To keep them safe on the big stadium shows, Evans and Sharpe often took a helicopter and hopped out close to the ring.

“I’ve had cab drivers try to run up on the sidewalk and hit me down there,” said Sharpe. “They took stuff very, very serious. I’m doing my job; I couldn’t blame them. It just made for very uncomfortable living situations sometimes.”

A decade later, Sharpe is back in Puerto Rico, acting as a mouthpiece for monsters Abdullah the Butcher and Bruiser Brody.

“I was lucky enough to be a mouthpiece for Brody and Abdullah because guys that are monsters really shouldn’t be able to speak, even if they can,” Sharpe said, thinking more of Brody, killed in a dressing room in July 1988. “When [Brody] first came to Puerto Rico, I saw him and I said, ‘That man’s going to get stabbed and killed here, but I always thought it would be by a fan.'”

Sharpe was not there when wrestler and office worker Jose Gonzales stabbed Brody, though he was never convicted. “I was managing him, and I actually got fired a week before that happened,” said Sharpe. “Brody was over like crazy. I was his manager. Gonzales had already beat everybody in the territory and then he wanted me to do a job for him on TV. In my opinion, he didn’t need to do that to get himself over. It would have been a meaningless match and, if anything, it would have just taken the heat off of me. I refused to do it, so I got fired that night. He was extremely jealous. I can remember one time he wanted to fight because I told him that I thought that Carlos Colon was a better babyface than he was. That’s how his temper was. From what I understand, the jealousy just got to him about Brody being over so much. I’d been home about a week when the incident occurred.”

A MASTER CLASS ON RING PSYCHOLOGY

Being able to teach someone how to wrestle in the ring is one thing, and being able to teach psychology, the art of getting people up out of their seats and reacting, is something different. Sharpe could teach that, and explain that too.

He was asked about how a good guy should behave.

“A great babyface was the easiest job in the business. The problem is they made it hard,” he said. “Like Rick Martel was smart enough, he would let you work on him, get your heat up on him, and you didn’t have to stop you and make a comeback every five minutes. He would just lay there and get his sympathy. Then when he came back, the place went nuts. With a lot of guys, you have to fight to keep them down, not because you wanted to look good, but they couldn’t wait to look good, they couldn’t stand selling that much.”

It’s simple, really.

“The heel is the ring general,” he said. “Sell. Let me do the work, and then I’ll fly around for you.”

Sharpe was both a realist, knowing that the wrestling business changed, but also romanticized the territory days.

“It’s one of the great things about that era, you didn’t have to sit down in the locker room, design a match, choreograph it, then take it out there, like a lot of guys do now. You could just play the hand that you’re dealt, and it made a great game,” he said.

REAL-LIFE BATTLES

In August 1988, Sharpe was diagnosed with leukemia. He went through chemotherapy for 23 months. On his website, other procedures were detailed: “He had a hole drilled in his skull the size of a quarter that allowed a tube to access his central nervous system directly. He had several bone marrow biopsies and a spinal tap. After 23 months, the doctors at Fox Chase [Medical Center] stated that Larry was leukemia free.” That led to Sharpe aligning the Monster Factory and his WWA promotion with the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

It was only one bump in a wild ride. Besides training wrestlers, Sharpe also worked at a golf club.

Though dyslexic, meaning that writing takes forever, Sharpe tried working on his memoirs and had high hopes. “Everybody I showed it to loved it. The writer loved it. The literary agent liked it,” he said, but a publisher couldn’t be found for the book he had titled Road Scholars. “I’m so disappointed that it didn’t fly.”

While there isn’t an actual “Pretty Boy” Larry Sharpe book out there, there are plenty of stories. Seek them out and learn from a master … and probably have a laugh in the process.

ONE LAST LAUGH

“Luscious” Larry Sharpe and “Ravishing” Ripper Collins did a tour of Japan together.

“It was like taking my wife with me. He’d wash my tights and hang them up, and do all the stuff that a female would do for you,” Sharpe said. “I’m going out trying to get laid and get drunk, and he’s staying home washing the tights and the socks and hanging them up.”

Later, they are together again in Hawaii, but since Collins was dating Watson, they would be off in a room together. One time, Watson’s mother came to town, so she moved in with her son and Sharpe was back with Ripper.

“They went sight-seeing. There was some big football game on … but I had Muraco, I had Mando Guerrero, all the rest of the boys were off and we all congregated in one room. You know how wrestlers are — they were pigs. The room was wrecked, it smelled like herb. Ripper comes back in from the sight-seeing, opens the door and puts his hands on his hips, looks around and says, ‘Why didn’t you just invite the pigs to come in with you!’ So he starts cleaning up the room right away — peanuts shells, this, that, fruit cores. He was mad. When he went to bed that night, the lights went out and I heard a yell. Mando Guerrero had stuck a banana peel in his pillow case.”

Plans for a memorial service will be announced at a later date. Arrangements will be made by Farnelli Funeral Home in Williamstown, NJ.