“Bruiser” Bob Sweetan, who died on February 10, 2017, after years of health issues, was one of those polarizing figures in the pro wrestling industry. On one hand, he was a solid hand in the ring, believable and intimidating, someone who influenced a young Shawn Michaels. On the other, he was a loner, disliked by some of his peers, and eventually deported back to his native Canada for sexually abusing his daughter.

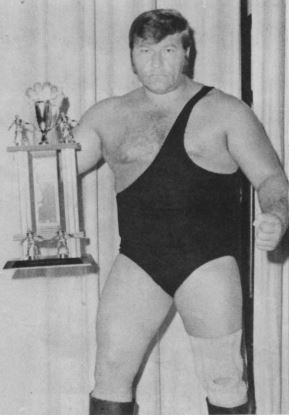

Bruiser Bob Sweetan

Starting at the beginning, he was born on July 4, 1940, on a farm near Goodsoil, Saskatchewan, about four hours north of Saskatoon. He’d grow into a 5-foot-10 man, thick of build and strong like an ox, who saw football as a way out of town. While he ended up briefly with the Canadian Football League’s Toronto Argonauts, he is not listed in any game reports, and declined to talk about it in a 2006 interview. “I don’t want to talk about that. It was a painful experience for me at the particular time, so I’d rather not discuss it,” Sweetan said in an exclusive, previously unpublished interview with this writer. It is also unclear when he changed from his family name of Beier to his legal name at the time of his death, Robert Carson.

Beier/Carson headed back west, ending up in Calgary. “I just got on the road and decided that I had to see everything, and started traveling,” he said. A chance knock on his door got him into professional wrestling, which was pretty prominent in town due to Stu Hart and his Stampede Wrestling promotion.

“A pot and pan salesman came to my door. His name was Gerd Topsnik. He was a wrestler, he wrestled part-time for Stu,” said Carson. “He tried to sell me some pots and pans. So I told him, ‘All right, I’ll buy your pots and pans if you get me started in wrestling.’ He started taking me to Stu’s and I started working out at Stu’s. The rest is history.”

Not long afterward, he was renamed Bob Sweetan. “I picked it out of the clear, clear, clear blue,” he said.

The oddness of the wrestling business, with its off hours and time on the road suited Beier/ Carson/ Sweetan. “It was a lifestyle that I thought I would like because I could work out when I wanted to, do what I wanted to do when I wanted to do it, and make decent money at the same time,” he said.

After starting with Stampede in 1965, he headed east the Maritimes, and then back to Calgary. Looking back, Sweetan had nothing but positive things to say about the Hart patriarch. “Stu was fairly fair with me. When I look at the whole picture overall, I think we treated each other very fair. I never had any complaints about Stu — there were a lot of promoters I had [complaints about], but not Stu.”

Bob Sweetan and Buck Robley. Courtesy Chris Swisher

From there, the road really was Sweetan’s home, as he worked with promotions in Oregon (promoter Don Owen), Arizona (Ernie Mohammad), Kansas City (Bob Geigel), Louisiana and Oklahoma (Bill Watts), as well as San Antonio, Texas, for Joe Blanchard, where he got national attention on USA Network.

Sweetan was his wrestling name most of the way through, aside from a stint as K.O. Cox in Texas. He took pride in his style in the ring. “I was a tight worker, everything was close. I don’t think there was anything that I ever did that didn’t look real — maybe at the beginning when I didn’t know what I was doing. But I always prided myself on hard work.” Given that he wasn’t that tall, Sweetan said he was always teased for that, despite weighing anywhere from 240 to 340 pounds during his career, but usually tipping the scales around 275 pounds. “I always got the saying, ‘Hey, you’re too small. You’re too small for this, you’re too small for that.’ I just had to prove them wrong. That was my motivation.”

“Cowboy” Dan Kroffat worked with Sweetan in Stampede and in Oklahoma in 1974, where Grizzly Smith was the local promoter. “He and I worked on top there. We changed the belt back and forth. I found him to be a great worker,” said Kroffat. “I had a lot of good matches with the guy. He was a pleasure to work with. But who knows what goes on outside the ring.”

Another regular opponent was Leo Burke. He considered Sweetan’s strengths and weaknesses. “He was a good follower. If you could lead him, he could follow you, like a dancing partner,” said Burke. “I’ve had better heels, but he was definitely a good one. He was kind of lazy sometimes. That would be his worst knock. He was easy to work with.”

In the Maritimes, where Emile Dupre and then the Cormier family — Burke’s brothers Rudy Kay and The Beast — promoted, Sweetan met Fred Prosser. In 1969, they became a tag team as the Sweetan brothers. Back in Calgary with his blond hair, Sweetan remembered Prosser. “I told Stu I’d bring this guy out and make him my brother, cousin, or whatever, and it went from there.”

The Sweetan brothers, Bob and Fred, in Stampede Wrestling. Photo by Bob Leonard

They were a good, solid team, recalled Stampede promoter and photographer Bob Leonard in a 2006 feature on Prosser and his mysterious death. “Bob always had good heat here (had a long tag run with Gil Hayes), and Fred fitted right into things. Bob tended to be the bombastic loudmouth, Fred more the strong, quieter brute of the pair.” Prosser was Killer Cox when he and Sweetan — as K.O. Cox — teamed in the U.S.

The teams with Hayes and then Prosser were part of a long list of tag team partners for Sweetan over the years. At various times, he held tag team titles with Mike George, Terry Gibbs, Dick Murdoch, Killer Karl Kox, Bulldog Bob Brown, Seigfried Stanke, Tony Rocco, Dick Slater, The Beast, and Paul Peller.

Yet away from the ring, Sweetan admitted he was a loner. “I kind of isolated myself from everybody else. I didn’t become good friends with anybody. They were acquaintances, people who were in the same business I was in. I used to travel, back when we were still traveling by car, I used to travel a lot by myself, maybe take one guy with me. I didn’t want to impose my lifestyle on anybody else, so if I traveled by myself, I could do what I wanted, when I wanted, and it’s not going to inconvenience anybody else.”

He continued to dwell on the past and his solitary nature. “I didn’t really socialize that much. I don’t know why. I think it made it easier for me, otherwise you’d socialize with a guy then three weeks later you’re in a town somewhere and you’ve got to go in there and wrestle the guy. That takes the edge off of things, I think.”

Like many wrestlers, the promoter was seen as an adversary. “I was kind of a head-strong individual. I’d stand up and speak for myself, and deal with the promoters. Some of the promoters didn’t like that, they just expected you to just say yes or thank you for the $100. … ‘I ain’t leaving this room until I get my money.’ Stories like that get around. It didn’t bother me, as long as I got my money. What I earned, I expected to get.”

Bob Sweetan and Gene Lewis (Gene Petit / Cousin Luke). Courtesy Chris Swisher

As for the fans, it’s fair to say that they never knew what they would get from Sweetan. Gene Petit, who was later better known as Cousin Luke in the WWF, knew Sweetan in Louisiana. “Bob was heel, babyface, heel, babyface. The people still loved him no matter what he did. If they hated him because he was a heel, they’d cause riots. Then he turned babyface, and they liked him because he was part of that territory and he belonged to those people, whether he was a bad guy or a good guy. If they brought a good guy in that those people didn’t know, and Bob was a heel, they might not care too much for that good guy. He might have been a bad guy, but he was their bad guy.”

A young Shawn Michaels saw the same thing when Sweetan worked in San Antonio, Texas. “One of our favorites was a guy named Bruiser Bob Sweetan. He was the first wrestler to come in as a bad guy, act like a bad guy, and be turned good by the fans,” wrote Michaels in his autobiography. “He came out to ‘Bang Your Head’ by Quiet Riot and would finish his opponents off with the piledriver. That got over like a million bucks, and the fans couldn’t help but cheer for him.”

Ah yes, Mr. Piledriver. He had a t-shirt to prove it, too.

Calm for most of the phone interview, Sweetan comes alive talking about his skills with the devastating move. “I’ve seen different guys use the piledriver. I don’t give a fuck how many guys try it, they don’t do it the same way I did it,” he said. “It looked like it was dead-on every time I did it. I don’t give a fuck, you could go out there with a camera right down there on the mat, right between my legs, you still would have sworn the man got jacked. Things I did, I tried to do them as solid as possible, as believable as possible. Most of the time — even ask the guys I worked with — I was stiff.

“I never hurt anybody in all the years I used it, I never hurt anybody. I did piledrivers off the apron onto the concrete floor, I did piledrivers four feet through a table on to the cement floor, guys weighing 260, 280, 300, 350, I never hurt one of them.”

At the end, though, Sweetan himself was pretty beaten up. He called it quits from wrestling around 1987, his last run for Rip Tyler’s promotion in Pensacola, Florida. “The body didn’t want to work anymore, too crippled up. I’ve got arthritis in every joint in my body. I abused my body for a long time, but it was all worth it. I enjoyed every minute of it,” he said.

Post-wrestling, he was a maintenance supervisor for air conditioning work, especially in big apartment buildings. “It was interesting, because I learned something new every day. I worked on my own time, when I wanted to, and how I wanted to do it. I was my own boss. That worked out fine.”

On the cover of a Mid-South Wrestling program.

Not everyone was a fan of Sweetan. Jim Ross was a referee for Watts, who got caught in a riot that Sweetan started in Lake Charles, Louisiana, for leaving Grizzly Smith in a bloody mess in the ring. “Bruiser Bob Sweetan, not the nicest guy I ever met in the in the biz,” wrote Ross on his website. “I followed Sweetan back to the locker room through angry, angry fans while Griz laid in the ring bleeding profusely. The rule of thumb was to always leave with the villains because that’s where the cops would be. They were there all right and doing all they could but that did not prevent me from getting punched repeatedly while navigating through the many irate, drunken alpha males who wanted to kill Sweetan for what he did to their beloved hero and me for allowing the heinous actions to occur.” Ross also told a story about Danny Hodge torturing Sweetan as payback for stepping out of line.

Sweetan recalled another riot in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, where the fans started throwing chairs into the ring. “Finally, I said, ‘Okay, this is it.’ Nobody came out of the dressing room to help my ass. I jumped out of the ring and went running back to the dressing room. They’d locked the fucking door and I couldn’t get in. I had to go up on the stage and go down another way to the fucking dressing room.”

Ed Wiskoski didn’t like Sweetan: “I wasn’t a fan of his … from being a locker-room thief to just among other things, just an asshole. … Whenever I was around him, I always locked up my shit, made sure that I didn’t have anything that I couldn’t afford to lose in the dressing room.”

Hacksaw Jim Duggan was not a fan either, calling him “just a mean guy and a bully” in his autobiography.

Of course, there are far worse things than not looking out for the referee or theft.

Rebecca Jane Terhune met her future husband in Kansas City, where he was wrestling in 1969. She’d been raised in Iowa, and left after high school. Rebecca was not a wrestling fan, though, and had never been to the matches; instead he saw her dancing at the adult club across from the K.C. wrestling office and something clicked between the two of them. They were married in Los Angeles in 1971, and had four children together: Candace was born in 1971; Christopher in 1974; Cathy (Cassandre) in 1976; Carson in 1978. (Sweetan has one more child with another woman.)

As K.O. Cox.

Like all wrestling relationships, there was a lot of moving — Calgary, Los Angeles, Bob off to Japan or Puerto Rico, settling into Baton Rouge, Louisiana; and then back to Kansas City. When she talked to this writer in 2006, Rebecca was in Pflugerville, Texas; she and Bob had a mobile home built in 1973, and they all settled in Pflugerville in 1982. “When I moved here, my children said, ‘Are we really not going to move again?'” she recalled. Again, like many wrestling relationship, some of their closest friends were other wrestlers and their families, like Grizzly Smith and his then-wife Marcia, or Ted DiBiase and his first wife Jeannette.

Though hardly exclusive to the individual nature of professional wrestlers, drugs entered the picture. Sweetan was not shy talking about it. “There wasn’t anything that I didn’t take or do. I enjoyed life to the fullest,” said Sweetan. “It was so easily available and it was all pharmaceutical. It was nothing made up in somebody’s bathtub or cooked up in somebody’s fucking kitchen, and who knows what the fuck is in it. It was all pure pharmaceutical stuff. It didn’t have that much damage to your body, if you did it within reason.”

Rebecca Carson knows the date all too well. Sweetan had a great wrestling career “until he fried his brain on drugs.” The result was many bad decisions.

Rebecca Carson with her son Carson on his 18th birthday. Facebook photo

Sweetan disappeared from the lives of his wife and four children on October 15, 1985, and from the world of pro wrestling. Bill Watts was Sweetan’s boss at that particular moment, and Carson called him after two weeks of not hearing from her husband. “I called Bill and asked where Bob was. He said, ‘Well, we don’t know. He just didn’t show up for work. We thought he went home.'” Days later, she call Grizzly Smith, whom she’d known for more than a decade. “I said, ‘Griz, you need to help me find out what happened to Bob. He was working for Bill. It’s your responsibility. You just tell me what you know.’ He said, ‘Well, he was dating this arena rat that was the drug dealer.'”

Knowing a little bit more, she called Watts back and learned that her husband had left his paycheque there, so at least she had some short-term money to raise her family. “We went all through Thanksgiving, Christmas, my birthday, no word. I was halfway torn that somebody had done him in because he had left and had never missed a day’s work in his life, no matter how beat up he was. And he’s never left a dollar. So what was I to think?”

Bob Sweetan and Mike George.

In January 1986, Carson hired a private investigator to find Sweetan. The P.I. succeeded, tracking him down in a rough part of the state near the Texas/Arkansas border. Carson then filed for divorce, and Sweetan did show up at the courthouse (with his girlfriend Stacy), where he walked by two of his children, Candace and Chris, without recognizing them. “He came in the courtroom, and he left the courtroom in a huff because he got nothing,” recalled Carson. “They left the courtroom and disappeared. That was April 29, 1986.”

Working 12 hours a day to support her kids, Carson struggled. Sweetan disappeared again, and wouldn’t be seen in Texas again until 1990, when he was brought in on charges for sexually molesting a child — his daughter, Candace.

Speaking carefully, Carson said that her daughter revealed the assault about a year after the divorce; Candace was 15 at the time of the assault. Charges were filed with the attorney general and a warrant was issued for Sweetan/Carson’s arrest. Eventually, Sweetan was apprehended in Pensacola, Florida, and brought back to Texas in January 1990, where he faced the felony charge over the sexual assault and a separate charge over non-payment of child support. Six months later, on July 9, Sweetan plead guilty to the sexual assault. Instead of further jail time, he was a part of a new program that required him to stay in touch with authorities, stay away from minors, and continue to pay the child support. “We didn’t have to go to court,” said Carson.

Bob Sweetan’s kids celebrate Carson’s birthday; from left, Cassy, Carson, Candace and Christopher. Facebook photo

From 1990 until 2000, Sweetan lived in San Antonio. “He paid all the child support, all the arrears and everything. When you’re a convicted child molester, you have to register the rest of your life and you have to register every time you change address,” said Carson. “Well, druggies are stupid. He stopped registering in September of 2000. My daughter is the dispatcher at the Pflugerville Police Department, so we still have some more police friends. I had the feeling he was gone. I could always feel him, I know that sounds stupid, but I felt where he was and proved it. I could always feel him. I said to my daughter, ‘I feel that he’s gone, I can feel him gone.’ So I had one of my officer friends in Pflugerville check with the person that handles the people that register. They found that he hadn’t registered.”

Instead of being imprisoned in Texas, he was deported back to his home and native land in April 2001. “I’m like an elephant, I’m coming home to die,” said Sweetan in 2006. The daughter he had with Stacy played hockey, which was a rarity in San Antonio, so she could play in British Columbia. Sweetan settled in Nanaimo, where his brother Leo lived.

In 1992, when Christopher, Sweetan’s oldest son, turned 18, Sweetan was allowed to visit Pflugerville. He met with Chris, Cathy and Carson, but not Candace. According to Rebecca Carson, her son wanted his father “to take responsibility, say he’s sorry for what he did to Candace and deserting them, and go on from there. Did he do that? No. He sat there and told Christopher, ‘Your mother made me leave. Your mother wouldn’t let me see you. Your mother wouldn’t let me talk to you. This is all your mother’s fault. I didn’t do anything. Your mother made Candace say that.’ When they all went to court and saw him convicted. When he lived in San Antone, Christopher tried two other times to go see him in San Antone. He just blew him off.” (Christopher Carson died on January 21, 2013.)

On the phone in 2006, Sweetan didn’t go into any detail about his family issues, but admitted he hadn’t seen his oldest children in over 20 years. As for the court time? “I just got a divorce, that was all.”

Sweetan did say that his body was falling apart; he was diabetic and didn’t get around much. Word is that his condition worsened and that he was confined to a Nanaimo nursing home with memory issues, where he died on February 10, 2017. He was 76 years old.

To Sweetan, professional wrestling was a good career choice. “I never really had any regrets because I knew that I could not survive in a constrictive environment where you do this, you do that, and you don’t shit until I tell you, no you don’t do this and you don’t do that. No, I got into the business because I was an independent contractor and that’s the way I was.”

His legacy outside the professional wrestling business, however, is something different. “He’s a waste of skin as far as I’m concerned,” stated Rebecca Carson. “He fried his brain, deserted his children, abused them emotionally, physically, sexually, mentally, whatever. But that’s what drugs do. He fried his brain. He’s a fried egg.”