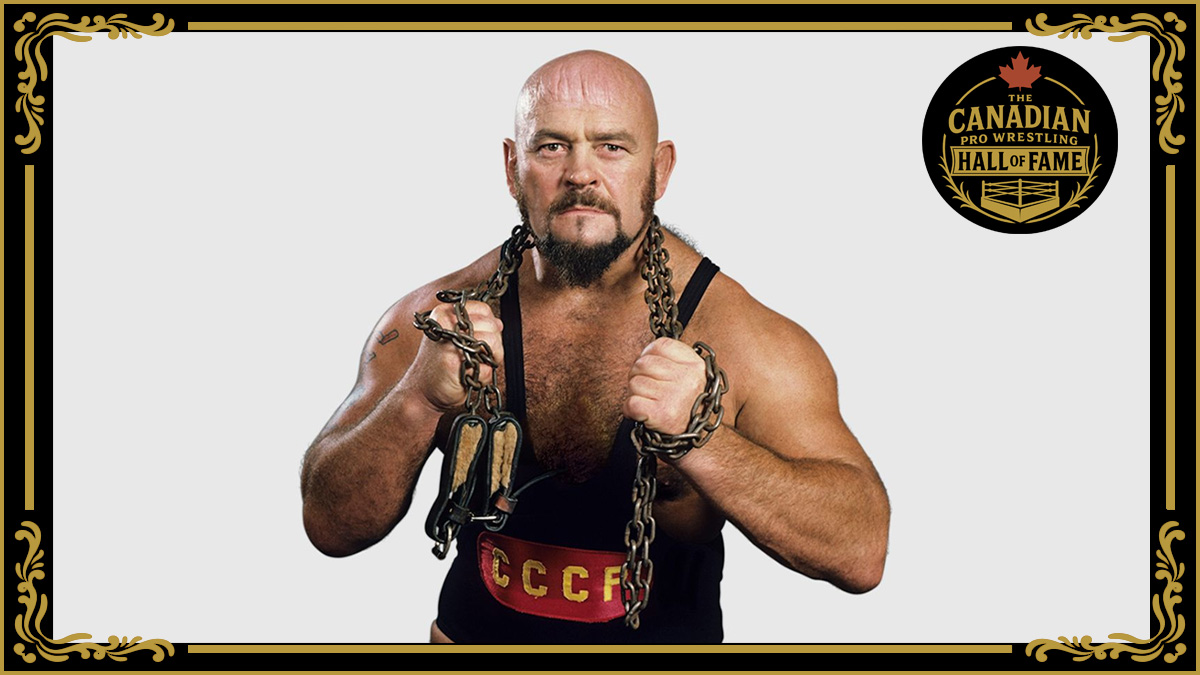

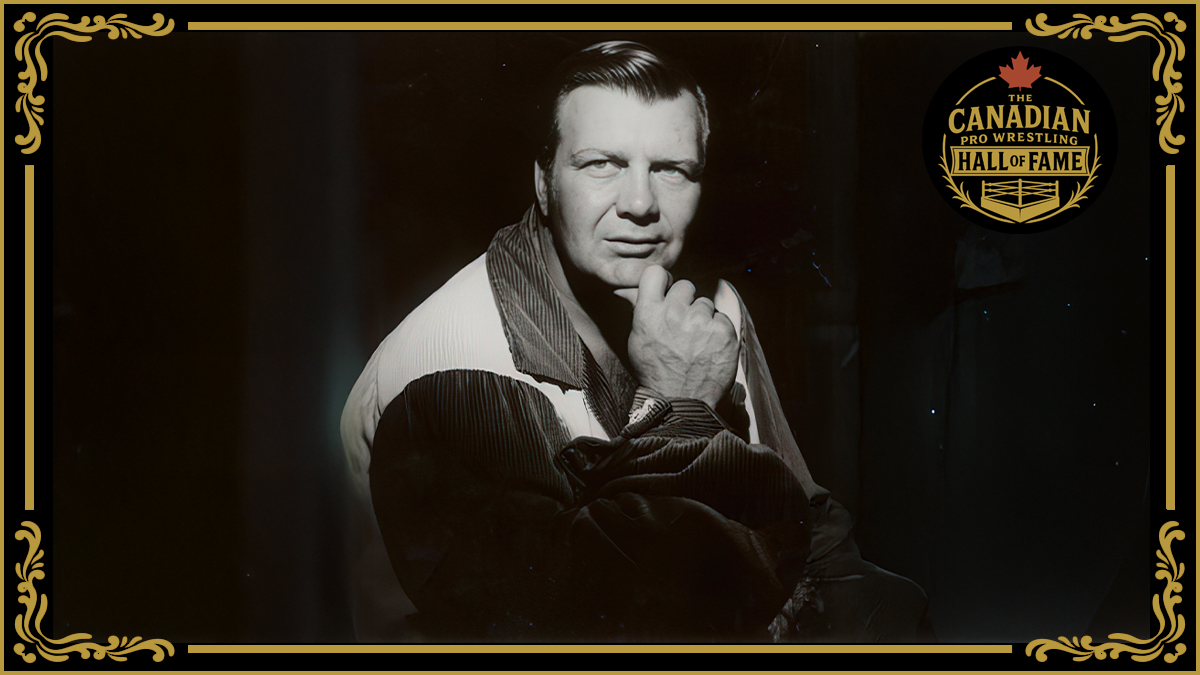

The date January 18, 1971 and Ivan Koloff will forever be connected. That was the day that “The Russian Bear” did the unthinkable, defeating Bruno Sammartino for the WWWF World title. Sure, he only held the belt for another three weeks before dropping it to Pedro Morales, but it made Koloff, who died February 18, 2017, at age 74, into a big name star.

But the first time Koloff wrestled Sammartino, he almost got himself killed. He filled in at a Pittsburgh TV taping as Red McNulty, an Irish villain with an eye-patch, when he gullibly bit on a veteran’s advice to attack Sammartino while he was making the sign of the cross before the match. “I ended up doing it and I remember Bruno looking up at me like, ‘What’s the crazy kid doing?’ He threw me around and I think he put the bearhug on me.”

What a strange world this is. Koloff’s victory over Sammartino in the middle of the ring in Madison Square Garden, scoring the greatest wrestling upset of the era and ending Sammartino’s nearly eight-year reign as WWWF world champion was game-changing. “Dead silence came down,” said manager Captain Lou Albano, who was in Koloff’s corner that night. “They couldn’t believe it.”

In a business loaded with foreign heels, Koloff stood out from the pack during his heyday in the ’70s and ’80s, even winning academic admiration from social critic Paul A. Cantor of the University of Virginia: “I wish I had a ruble for every wrestling villain who was advertised as the ‘Russian Bear.’ But the greatest of all who bore that nickname was Ivan Koloff. Looking for all the world like Lenin pumped up on steroids, he eventually spawned a whole dynasty of villainous wrestling Koloffs.” Koloff was more than hammer and sickle, though. Ronnie Garvin considered his work to match his gruff Russian image. “Ivan was a good worker. He looked more Russian than a lot of Russians and he had a better accent. He probably didn’t need it. But that was his gimmick, his style. He was very, very efficient.”

Jacques Rougeau Sr. was instrumental in changing Koloff’s nationality during a swing of Japan. Impressed with his work, he suggested McNulty — born French-Canadian Oreal Parras — shave his head and work for his brother Johnny Rougeau, who was running Quebec. Koloff fulfilled a few commitments, then went to Ontario to tell his family about the big change. “I stopped in to see my brothers around the Hamilton area, had a few drinks too many, and I was telling them I had to shave my head. So next morning I woke up, I had toilet paper all over my head,” he said. In Montreal, Koloff was billed as a nephew of Dan Koloff, a top wrestler in the territory 30 years before. “He was a very convincing guy,” Jacques said. “He did great for us.”

If there was any doubt about the demise of Red McNulty, Jimmy Valiant figured it out a few years later, when he encountered Koloff, half-asleep, in the Richmond, Va., airport. Ever the ribber, Valiant tells the story of how he coaxed an airport employee to page Red McNulty. No reaction. He did it a second time — “paging Red McNulty.” Koloff barely lifted his head, grumbled, “Red McNulty is dead,” and went back to sleep.

Koloff, who was born on August 25, 1942, grew up on an Ontario dairy farm in the Ottawa valley with nine brothers and sisters, and got hooked on wrestling when he first saw it on TV at a friend’s house at age eight. But he also got into his share of scrapes before becoming a pro. He quit high school two weeks before graduating from 11th grade after a suspension for playing ping pong during class time. Later, he recalled, he and a brother served time for stealing cattle, a serious crime in an agricultural community. In 1960, he landed with famed Hamilton trainer Jack Wentworth, who gave him the McNulty name. Scarfing down food and protein shakes, he beefed up to 230 pounds within six months and started working small shows. “I had super gains,” he recalled. “I really wanted to wrestle. I wanted it bad.” In Montreal, he set himself apart from the pack with a unique, fast-paced entrance and exit that he took to the WWWF. “They had me run from the dressing room, all the way to the ring, run around the outside of the ring about five times, and then while they announced me and my match, I’d jump in the ring as they announced my opponent and attack him, beat him up, then jump out of the ring and run around the ring three, four times, back to the dressing room. At 280 pounds! I was one blown-up guy. But it helped keep me in shape.”

Koloff was touring Australia and Hawaii when he was called back to deliver the kneedrop heard ’round the world against Sammartino in 1971. He was a transitional champ, holding the belt for three weeks before dropping it to Pedro Morales. But it kicked off a rivalry with Sammartino that ran for years. “I wrestled Koloff — oh, my goodness, I don’t know — 50, 75 times,” Sammartino said. “The reason why I enjoyed wrestling him so much was that after each match when I left and went back to the dressing room, I felt in my heart that the fans who came out and bought that ticket, that they went home feeling they got their money’s worth.”

Though his reign was brief, Koloff continued to main event across the country. He was on top in the Mid-Atlantic for years, starting in 1974 and was a frequent visitor to the WWWF. “What a heel of a hell he was,” said top NWA referee Tommy Young. “He wasn’t real tall, but thick as a brick; great performer. He was very professional, knew how to get the heat, was willing to do whatever he needed to. I can’t say enough about Ivan.” Koloff held part of the world tag title in the Mid-Atlantic five times with teammates such as Don Kernodle and nephew Nikita, even though the days of kneejerk anti-Soviet sentiment were passing. “He was a very methodical type of person in the ring. He lived his gimmick to the fullest extent while he was in that ring,” explained veteran Bill White. “The Russian gimmick suited him and that’s why he continued with it even after the Russian deal was over. He could make the people believe he could be that mean and that vicious, and that’s what counted.”

But Young was just one of many who noticed that Koloff was fighting demons outside the ring. “If he drank liquor, it was Lon Chaney turning into the Wolfman, just a totally different personality, mean, wanting to fight,” Young said in The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: The Heels. Koloff traced his substance abuse to a youth where booze flowed freely, and a bad bump in a Minneapolis match that ruptured discs in his back. He took painkillers, sleeping pills, and muscle relaxers for about 18 months so he could keep working, and started to rely on stronger stuff. “I ended up taking them and getting into situations where even the drugs weren’t enough. Looking back, I could say, ‘Well, I deserve it. I worked hard. I get up every morning and go to the gym and work out. I work hard in the ring, so I need this for my body. It’s OK then to not only take these drugs, but to find some relief in marijuana.’ And marijuana wasn’t enough, then maybe cocaine.”

He quit wrestling full-time in 1989 when Ted Turner acquired the Carolinas promotion and consolidated headquarters to Atlanta, though Koloff turned up in small promotions in the early 1990s with wrestling nephew Vladimir. His life turned for the better in 1994 when Nikita, a minister, persuaded him to attend church services and give his life to the Lord. Koloff ditched his vices — alcohol, drugs, and tobacco — and started a ministry in North Carolina with wife Renae. He would appear at detention homes, prisons, youth groups, and churches, though he laced up the boots for a few legends matches on occasion. “When I started straightening up, things started working in my life,” he said. “Once I understood that, that it wasn’t going to be on my power, it was going to be on His power, I now had a tag team partner who truly was a world champion.”

In 2007, he teamed with author Scott Teal to publish his autobiography, “Is That Wrestling Fake?” The Bear Facts. Teal posted a note to Facebook about working with Koloff after learning of his death: “This is one that really hurts. Ivan passed away this morning from liver cancer. Ivan was another one of those ‘heels’ who was a scary individual in the ring, but outside, he was a gentle soul who loved everyone. When his wrestling career ended, he spent his time sharing his love for God with everyone with whom he came into contact. God bless you, Ivan, for your friendship through the years.”

Though he has not been honoured by the WWE Hall of Fame — despite being the company’s third champion — Ivan Koloff was inducted into the Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame in May 2011 by his peers and historians. The Cauliflower Alley Club celebrated Koloff as well in 2013. presenting him with its top honour, Iron Mike Award, named after the Club’s founder, Iron Mike Mazurki. Introducing Koloff was “The Boogie Woogie Man” Jimmy Valiant. “I’ve always considered Ivan family,” Valiant said. “He always made his opponent better than he actually was.”

Koloff credited the fans, many of whom were in attendance in the room of 600 at the Gold Coast Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas. “They lived to watch me get beat up,” he said, referring to himself as a “nasty old Communist Canadian Russian Bear.”

About a decade ago, Koloff was diagnosed with liver disease, and had kept the news relatively quiet, choosing to continue to live his life, and, in the words of his daughter Rachel Marley in a GoFundMe campaign to raise funds for her father, “he wanted to follow doctors orders and keep on going out and spreading God’s Word.”