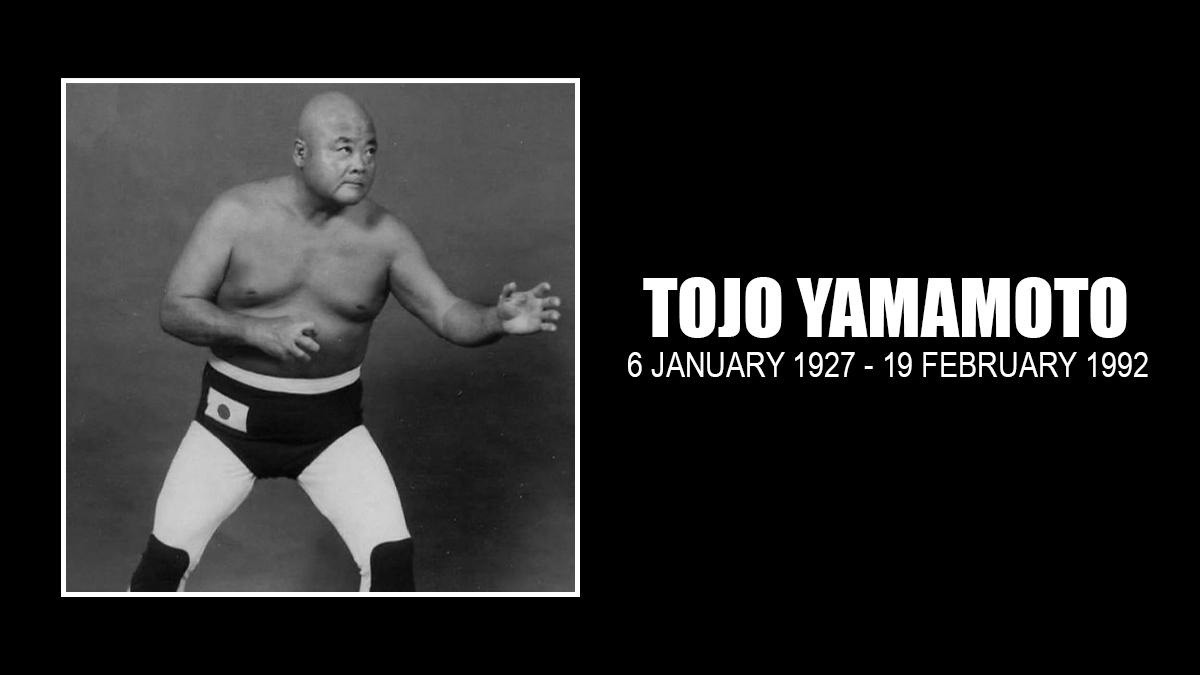

Tojo Yamamoto has been gone for 24 years now. When he took his own life, he affected a great many people, including a number of wrestling personalities that he impacted, from the Jarretts to Jerry Lawler.

He was born Harold Watanabe in 1927 in Hawaii to a Japanese father and Hawaiian mother. Watanabe served in the United States Marine Corps and was a judo instructor.

Watanabe began wrestling in the late 1950s as P.Y. Chung throughout the Northeast and in the Carolinas. However, the Hawaiian native combined the names of former Prime Minster of Japan Hideki Tojo and former Japanese Marshal Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto — two names synonymous with the bombing of Pearl Harbor — to create the moniker Tojo Yamamoto.

He was not the first grappler to adopt the guise of a hated Japanese heel, but Yamamoto was one of the most long-lasting, playing his part to the hilt decades after the United States and Japan became allies.

“World War II was long since over, but it was rekindled every time he came to the ring. He’d hit you with that chop. The first one, it’d raise blood blisters. The second one, it’d open them right up,” explained the late veteran Tennessee hand Randal Brown. “When the ref turned his back, he’d hit you in the throat and then walk around for three minutes pointing to how smart he was. Half the people wanted to kill him and even the people who liked him wanted to kill him.”

Watanabe homesteaded in Tennessee with some exceptions such as a stint as T.Y. Chung in West Texas in late 1967 and early 1968. Yamamoto became a household name in Tennessee while working for NWA Mid-America headed by promoters Nick Gulas and Roy Welch. He was also quite the heat seeker in the South and could generate riots.

“One of the best bad guys that I ever saw was Tojo Yamamoto, and the reason that I say that is that Yamamoto could turn an audience with a look like almost nobody else I ever worked with,” recalled legendary announcer Lance Russell. “He didn’t do any more than just cut his eyes or drop eyebrows down — something like that. He just was an absolute master at being able to get across what he had in mind about being a sneaky Jap. This is what he was portraying as he did all this. He was one of the best.”

In an often told story, Yamamoto was booked in Boaz, Alabama. He asked to make a statement prior to the match, and the crowd booed. In broken English, he lamented, “I wish make apology. Very sorry my country bomb Pear-uh Harbor.” The audience quieted and expressed sympathy while Yamamoto wiped away tears. He continued, “It was wrong thing to do, I wish not happen,” and the spectators applauded. Yamamoto exclaimed, “yes, I wish not happen because instead I wish they bomb Boaz!”

Yamamoto’s first known title was the Florida version of the NWA United States Tag Team Championship, which he won with Taro Miyake (George Kahaumia) on November 16, 1961 in Jacksonville.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, Yamamoto held the NWA Mid-America World Tag Team and Southern Tag Team championships with a multitude of individuals including Alex Perez, Professor Ito, Johnny Long, Jerry Lawler, and Gypsy Joe just to name a few.

Len Rossi, who wrestled Yamamoto numerous times, said you had to earn his respect: “Tojo was a funny person. If he thought he could get away with it, he’d hurt you, but if he didn’t, he would not. He had the sneakiness down pat. He was a master of that.”

Yamamoto also became a mentor to a young Jerry Jarrett, whose mother Christine Jarrett, worked in the Nashville office for Gulas and Welch.

“Nick Gulas and Roy Welch, hired me on the weekend to go pick up the money from various promoters that had events in small towns around the large weekly towns,” Jarrett explained. “I was not welcome in everyone’s car because the office told them that I would not pay ‘trans’ — trans was the fee the driver of the car would charge his passengers to cover gas and wear and tear to his auto. It ranged from five cents to 15 cents per mile. Tojo traveled alone most of the time, so he allowed me to ride with him.

“I was still in high school and my first impression was how nice and polite this mean guy that I booed at the wrestling matches was,” Jarrett continued. “I had been taught to speak when spoken to, and Tojo later told me that he liked the fact that I had good manners. Sometimes we would take a two- or three-hour trip and not say one word. Sometimes we had very deep conversations concerning the difference between Eastern and Western philosophy, or various religions, or the advantages and disadvantages of capitalism and socialism. I was always intrigued by the depth of his knowledge.”

Jarrett soon began refereeing matches for Gulas and Welch while forging a friendship with Yamamoto over the next few years.

“One day he said, ‘You smart boy, but sometime you do dumb things. You make $15 or $25 refereeing matches. Why you not wrestle and make $100 or $200?'” recalled Jarrett. “I made the mistake of answering, ‘Oh I’m too little to be a wrestler.’

“I experienced the verbal wrath of Tojo,” Jarrett continued. “He threatened to stop the car. Tojo shouted, ‘I show you I’m not too little to beat your ass!’ I profusely apologized and explained that I considered him a big man, and that I was only referring to my body size and not height. I was in fact several inches taller than Tojo. I realized that height was a real hang-up with Tojo and the real reason he wore the wooden shoes. The shoes made him three inches taller when he walked through the crowd on the way to the ring.”

The short and stocky bad guy was not afraid to use his wooden shoes in or out of the ring. In a newspaper clipping dated July 8, 1969, a 27-year-old fan named Tom Barnes sustained injuries and bruises from being struck by wooden sandals and belts carried by wrestlers the previous night. The Memphis Police Department issued assault and battery warrants for Yamamoto, Johnny Long and Mack York as a result of the melee.

Yamamoto was no stranger to lawsuits. In January 1971, Circuit Judge Howard Vorder Bruegge declared a mistrial in a $18,500 damage suit against the wrestler.

Yamamoto began teaching Jarrett how to work; however, the Jarrett matriarch was not keen on her son becoming a wrestler.

“My mother knew that because she worked in the wrestling office, I would get heat from some of the boys because they would think I got preferential treatment as to bookings,” Jarrett explained. “She knew Tojo and I were good friends, and she didn’t trust him to discourage me. Sailor Moran was a shooter with quite a reputation. She told me she wanted Sailor to teach me to defend myself in the event some jealous wrestler tried to hurt me in the ring. Sailor proceeded to discourage me in the name of shoot training. Tojo was smart to the scheme and encouraged me to keep training.”

Yamamoto’s first major babyface turn was rescuing Jerry Jarrett from a beat down. In his book The Best of Times, Jarrett described the events leading up to the angle: “I began wrestling on Memphis television and Lance Russell and Dave Brown, our announcers, began planting the seed that I was making improvement from week to week … After we had laid the background that I was making great improvement as a wrestler, we revealed that Tojo had taken me under his wing and kind of adopted me as his protégé. I was taking a sound beating one match, and Tojo came to my rescue.”

Yamamoto and Jarrett immediately formed a successful tag team. The duo went on to win tag team gold on at least seven occasions.

Jerry’s son, Jeff Jarrett, also recounted his memories of Yamamoto in a telephone interview.

“My first memories of Tojo would have to be me going to watch him wrestle with my dad as a partner,” recalled the Global Force Wrestling CEO. “My dad and Tojo were almost polar opposites as far as personas, and the team just clicked with the fans.”

Yamamoto also trained up-and-coming wrestlers such as Jeff Jarrett, “Beautiful” Bobby Eaton and “Wildfire” Tommy Rich.

“Tojo was more about selling, facial expressions and the psychology that goes with the training,” Jeff Jarrett explained. “He was very, very adamant on just conveying emotion. He’d say ‘don’t have stone face.’ He had all types of one liners that basically meant don’t be a dead fish — and convey emotion. He was really a stickler for that.

“He was very serious about the business,” Double J continued. “Riding up and down the road early in my career, he would say, ‘You need to listen to your grandmother. She is a good businesswoman because she works hard. Your father works hard, you need to work hard.’ We would ride together four or five days a week at times, and I would get that speech just about every trip.”

Utilizing his knowledge of Judo, Yamamoto did not hesitate to use his karate thrusts against rookies.

In a November 1992 interview with NBC Nashville affiliate WSMV, Hulk Hogan described Yamamoto’s rough and tumble style from his Tennessee wrestling days.

“I remember one time he hit me in the throat, boom, with this cheap shot,” said Hogan. “And I fell through the ropes … I thought he was going to beat me up on the floor, and what he did was he grabbed a cigar out of a guy’s mouth and dropped it in my boot. I was jumping around like a jack rabbit, it hurt so bad, trying to get my boot off.”

A young Jerry Lawler also felt Yamamoto’s wrath. The late Jackie Fargo set up Lawler’s first real match in Jonesboro, Arkansas in a bout against the Japanese heel.

In his autobiography It’s Good To Be The King … Sometimes, the WWE Hall of Famer described the matchup by writing, “He chopped me on the side, then threw me on the rope and chopped me on the head coming off the rope. Chop, chop, chop. All I did was sell his chops, which was very easy to do because he hit me real hard. He didn’t pull them at all. My chest was read, and I had handprints all over me. He also had this move, called ‘The Claw,’ that he applied. It was horrible. For fifteen minutes, he just beat me up.”

Lawler would seek revenge years later with a rib on Yamamoto.

“Tojo was getting ready for a match, and I snuck into his locker room and climbed on top of the lockers while he was in the rest room,” recalled The King in a 2015 interview with The Jackson Sun. “The only thing in the world Tojo was afraid of was snakes, and I had a very realistic-looking rubber snake that I threw down on him when he was lacing up his boots. I gave myself away when I started laughing at him when he started jumping and screaming, and he actually pulled a gun on me out of his bag screaming, ‘I shoot you, you son of a gun!’ He’d never cuss, but he was ready to shoot me that night.”

In 1977, Jerry Jarrett split from Gulas and NWA Mid-America to form his own wrestling promotion under the name of Continental Wrestling Association (later named Championship Wrestling Association). Yamamoto remained loyal to Gulas and did not jump ship.

In his book, Jarrett described Yamamoto’s choice by writing, “We had our ups and downs over the years and I was especially hurt when he didn’t go with me when I first started my own promotion, instead staying with Nick Gulas. When Nick folded his promotion, Tojo came back to work with me. Our personal friendship resumed as if nothing ever happened. We never discussed his reasons for not coming with me.”

Fans never seemed to tire of his evil Japanese gimmick even into the 1980s. Rossi surmised the ethnic angle might have meant even more in Tennessee because Tojo was such a foreigner to the South.

“If you were from the North, you were a foreigner here back then,” Rossi explained. “Now, imagine someone from another country.”

Yamamoto wrestled until about 1986. After the Tennessee and Dallas wrestling promotions combined, he managed several wrestlers throughout the remainder of the decade and early 1990s, including Phil Hickerson who was billed as P.Y. Chu-Hi as an homage to Watanabe’s earlier wrestling names. The duo even led a sneak attack on “Gentleman” Chris Adams’ wife in a feud.

A young Steve Austin also crossed paths with Yamamoto around this time.

In his autobiography The Stone Cold Truth, the Texas Rattlesnake described a conversation he had with Yamamoto at the Dallas Sportatorium: “He said, ‘You have to know how to sell.’ Then he told me to grab his ear. I grabbed his ear, and he went crazy with pain and sank to the floor. I thought I had really hurt him. Then he looked up at me and smiled. ‘You get it?'”

Another memorable involved Jeff Jarrett dumping a can of yellow paint on Yamamoto at the WMC-TV Channel 5 studio in Memphis; however, the team of Akio Sato and Tarzan Goto aided their manager by incapacitating the young Jarett as Yamamoto enacted his revenge with a Kendo stick.

“The studio floor was super slick with yellow paint,” Jeff Jarrett recalled. “I do remember the Kendo stick hits that followed up. He was vicious, and Tojo would let you have it. He came from an era of realism and believability. We worked that feud for many months and did very well with it.”

Yamamoto led a private life, and some of Yamamoto’s colleagues never knew he had been married and divorced twice.

“He was very much a loner, which is an understatement,” added Jeff Jarrett. “He would go grocery shopping at midnight to avoid contact with people. Some people don’t know this, but he was a fantastic cook. He made great sauce and Hawaiian food. My fondest memory of him outside of the ring is just what a good cook he was.”

Russell described Yamamoto’s cooking abilities in a 2006 Opening the Vault wrestling segment, “Outside of the ring, Tojo taught my wife and myself to love shumai, or dumplings, and other Chinese food that we ate.”

In later years Yamamoto suffered from kidney problems and severe diabetes that forced him away from the mat in 1991.

“I knew Tojo was not himself, but I attributed his slowing down to aging,” recalled Jerry Jarrett. “I had no idea how sick he was. A couple of days before his death, I begged him to come stay at my house and let my wife Deborah cook for him. I explained that I knew he enjoyed his privacy, and that I had a full apartment in the house. He refused the offer.”

On February 19, 1992, Harold Watanabe ended his life with a self-inflicted gunshot from a 25-caliber pistol. He was believed to be age 64 at the time of his death and left a handwritten will and note thanking his apartment manager for the kindness she had shown him while he was sick.

Shortly after Watanabe’s death, the USWA chose to end their weekly broadcast with a statement about Yamamoto.

A somber Dave Brown stated, “We’re not going to do our normal closing of our program today because this week we lost a man who became a legend. Tojo Yamamoto gained fame as one of the bad guys of wrestling. He was known to be sneaky, he was known to be mean. He made the judo chop, the abdominal grab and wooden shoes infamous, and he won a lot of matches. But later on he became a teacher of young wrestlers, a favorite of the fans and he teamed with Jerry Jarrett to win some tag championships. They were a great team. In the ring, he was as tough of a competitor as ever stepped into a wrestling match. Away from the ring, he was a gentle man who loved wrestling, and he defended the sport whenever he was challenged. Even proud warriors sometimes have demons. For Tojo, they came as serious health problems, and he apparently chose to defeat them in his own way. Even though Tojo Yamamoto is gone, his legend will live in the memories of wrestling fans for a long, long time.”

Watanabe’s dying wish was to be cremated and his ashes spread over the Tennessee River because he drove over the body of water to and from wrestling matches for years.

Watanabe had also meticulously placed his possessions in boxes with a name on each box prior to taking his own life. Inside Jerry Jarrett’s box were two pairs of wooden shoes, several robes and publicity pictures of the duo together.

“During our long road trips, Tojo had explained that Eastern and Western philosophy were very different regarding death,” recalled Jerry Jarrett. “He said, ‘I love my life now. I love the long trips and I love wrestling. I will not love life when I am old and can’t do what I love.’ I should have expected him to end his life when that time came, but it was a total shock to my brain. I was angry with him for a long time. However, time heals and I remember the good times like sell outs, fishing trips and vacationing in Hawaii. I am thankful that God put Tojo in my life. I would not have had the great wrestling life without him.”