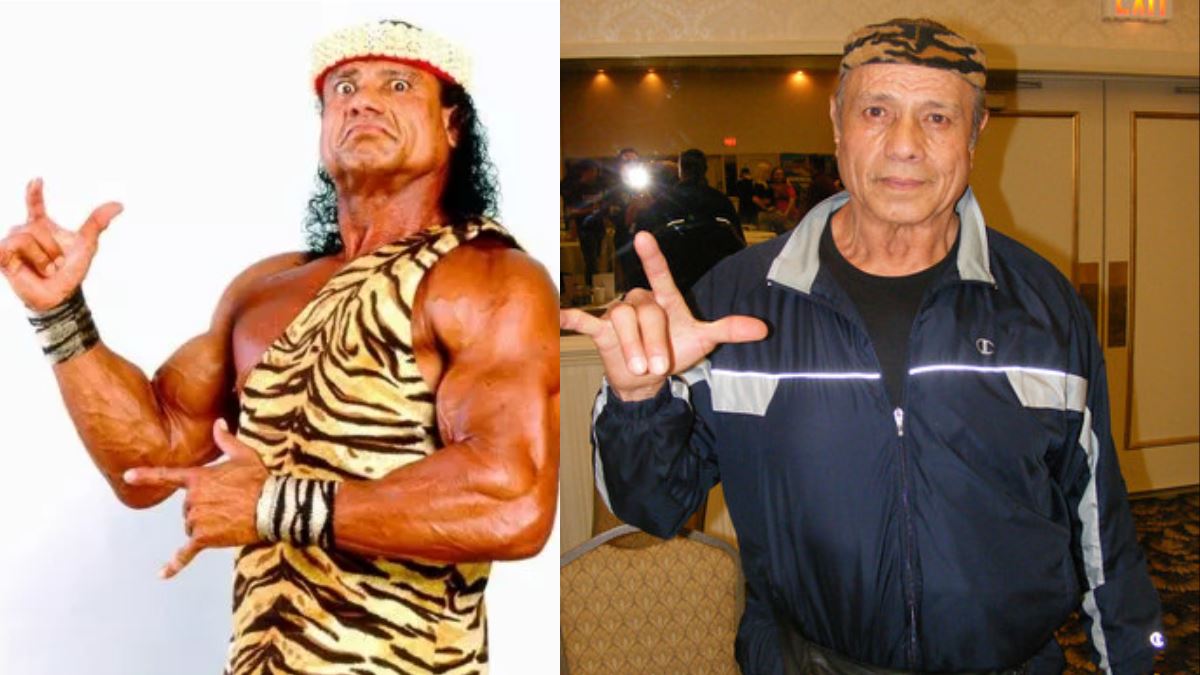

The better-late-than-never murder indictment of Jimmy “Superfly” Snuka in the 1983 death of his girlfriend Nancy Argentino once again challenges us with one of the main socially redeeming features of pro wrestling — an alternative universe that is all about life imitating art.

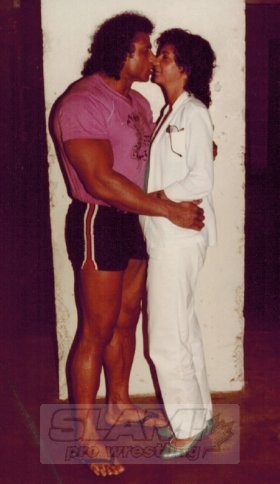

Jimmy Snuka kisses Nancy Argentino

Indeed, since there’s no accounting for taste, and wrestling’s gleefully pandering interpretation of what sports-entertains people isn’t everyone’s cup of tea, the genre’s occasional confrontation with death may be its only redeeming feature. Evidently, the human condition requires the inflation of the stakes to the level of the ultimate “work,” in order to make us pay serious attention to the reality that the ultimate lesson of wrestling is that it is just like that other world, only perhaps more so.

When Chris Benoit murdered his wife and their seven-year-old son in Georgia in 2007 before taking his own life, most fans and others were content to contain the backstory in a box that reduced the key question to breaking down what combination of lifestyle instability, drug abuse, and brain damage had driven this consummate professional and seemingly nice guy to “go postal.” My dissenting book, Chris & Nancy: The True Story of the Benoit Murder-Suicide and Pro Wrestling’s Cocktail of Death, examined the police and other public records to ask deeper questions about how powerful corporations collude with authorities to manipulate and domesticate public opinion. I called the Benoit story “a conspiracy between those who care too much about wrestling and those who care too little.” The resulting narrative might have been ungainly, but I’m still convinced it was on the right track in terms of helping to prevent “the next Benoit.”

The Superfly Snuka cold case tells a related but otherwise much different story: manipulation across a very long period of time. As such it’s a fascinating study of the industry’s history.

When Snuka allegedly killed Ms. Argentino in an altercation in their Whitehall, Pennsylvania, motel room, he was the No. 1 star of the Northeastern U.S. territory, whose promoter was just months away from launching and winning the national promotional war. That war, sparked by the growth of cable TV, bred the success of what is now WWE, a global corporation traded on the New York Stock Exchange with market capitalization of more than a billion dollars. Only a year earlier, Vincent Kennedy McMahon, in a highly leveraged deal that required less than $1 million in cash, had purchased from his father and his partners Phil Zacko, Gorilla Monsoon, and Arnold Skaaland the World Wide Wrestling Federation-founding Capital Wrestling Corporation, and rebranded it as Titan Sports / WWF.

Snuka’s violence against the women in his life, wives or otherwise, was of a pattern that corresponded with the unprosecuted abuses of celebrities, whether major or (as even a star wrestler was in those days) minor. But as fate would have it, the Argentino incident played out while he was in town for the tri-weekly WWF syndicated television tapings at the Agricultural Hall in the Allentown Fairgrounds. Allentown — all of Eastern Pennsylvania, really — was a small-scale WWF “company town.” The local cops worked off-duty private security at the matches; the local accommodations, such as the George Washington Motor Lodge in Whitehall, profited from a welcome mat defined, in part, by sweeping scandals inside the closed doors of the rooms they rented out.

The original police investigation, which was shut down within weeks, was a joke. Whether or not McMahon carried a briefcase into the June 1, 1983 meeting with Lehigh County prosecutors and police investigators, and whether that briefcase contained cash for bribes or just back issues of the Daily Racing Form, is a smoking gun teased by Snuka’s characteristically incoherent 2012 autobiography. For me, the briefcase, if it even existed, is almost beside the point. Who’s to say the Centimillionaire Man even had to pay anyone off?

In 1992 — for an article commissioned by the Village Voice but not published in print until 15 years after that, in my book Wrestling Babylon — Gerald Procanyn, Whitehall Township’s chief of detectives, lied to my face by maintaining that Snuka had given a single, consistent account of Nancy slipping on the side of the road and hitting her head when they stopped to urinate on the drive into town.

Perhaps Procanyn didn’t know that I’d already spoken with Lehigh County coroner Wayne Snyder, who had been deputy coroner nine years earlier, and he told me, “Upon viewing the body and speaking to the pathologist, I immediately suspected foul play and so notified the district attorney.”

Interviewed shortly thereafter by Penthouse magazine writer Jeff Savage, Procanyn reversed field, offering a more equivocal interpretation of Snuka’s credibility.

By 2013, when the Allentown Morning Call published a 30th anniversary retrospective on a cold case the newspaper itself had conveniently never covered in depth, Procanyn was a retired cop double-dipping on his municipal pension as a detective for the D.A. For this new article, he completely walked back his ’92 account: the peed-by-the-roadside scenario was now the story Snuka “hung with the best.”

The Morning Call coverage, following by weeks the publication of my ebook with the Argentino sisters, Justice Denied: The Untold Story of Nancy Argentino’s Death in Jimmy “Superfly” Snuka’s Motel Room, embarrassed District Attorney James Martin into revisiting the dormant, but still technically open, case. Martin is a former assistant and protege of William Platt, the D.A. in ‘83, who is now a senior state judge. Incredibly, the listless and lying Procanyn, defended by Martin as a “tenacious investigator,” was still on the case, too.

I believe the “fresh look” by the D.A. still would not have resulted in a grand jury probe had Louise Argentino-Upham and Lorraine Salome, Nancy’s surviving sisters, not continued to follow up aggressively.

I further believe the grand jury itself might have petered out with a whimper, rather than with the bang of an indictment for third-degree murder and involuntary manslaughter, had the Argentino sisters and I not gotten into a kerfuffle with the Morning Call over an op-ed essay accepted for publication in the fall of 2014, sat on for months, and finally pulled and published at the Wrestling Observer website.

Meanwhile, additional reporting exposes how the corruption and cronyism of the criminal justice system in the Lehigh Valley is hardly isolated to the Snuka case (just as the paradigm, no doubt, is hardly isolated to the Lehigh Valley). Earlier this year, thin-skinned D.A. Martin filed a free speech-chilling defamation lawsuit against Bill Villa, a local blogger who has written about how the privileged drunk-driving killer of Villa’s 25-year-old daughter was coddled by both Martin and Court of Common Pleas Judge Robert Steinberg (who was another assistant D.A. of now-Judge Platt at the time of the Snuka non-prosecution in the eighties). The drunk driver, Robert LaBarre, is the son of a partner at the law firm that both represents the Morning Call and has represented Martin himself.

“Sports entertainment” is part of life. As for the gap between how the system is described in our civics textbooks, and how it really works — well, that is a matter of life and death.

RELATED LINKS

- Jimmy “Superfly” Snuka story archive

- Irv Muchnick’s CONCUSSION INC. website

- Irv Muchnick on Twitter: @irvmuch

- Guest Column story archive

JUSTICE DENIED: The Untold Story of Nancy Argentino’s Death in Jimmy “Superfly” Snuka’s Hotel Room, annotates Muchnick’s original 1992 article and benefits a women’s shelter in Nancy’s memory. You can order the ebook for $2.99 on Amazon Kindle or a PDF copy by email (send $2.99 via PayPal to nancyargentino@gmail.com). One hundred percent of the proceeds are donated by the Argentino family, in Nancy’s memory, to the women’s shelter in development at the Salerno, Italy, church Centro Evangelical dei Fratelli. Muchnick’s website is ConcussionInc.net.