You can’t tell the story of Jerry Kozak, who died last week, without telling the story of his brother. And you can’t tell the story of Amarillo, Texas, without talking about Jerry Kozak.

The tale begins a long way from Texas, though, in Vancouver, BC.

The Kozak family has its basis in the Ukraine, where their father, George, came from, and Edmonton, where he met their mother, Martha. George Kozak was a big strong man, working in the logging camps, until getting hurt. There were four Kozak children: Nick was the oldest, born November 3, 1932; Jerry followed on September 4, 1934; their sister Anna was a year younger than Jerry; Dolores came around nearly a decade later.

Unable to work at the logging camps, George turned to his first love of music.

“He started making violins, him and mom both. He got quite a name for himself in and around Vancouver,” recalled Nick Kozak in 2004. “He wanted me to be a violinist. He wanted me to be what he wanted to be. I studied classical up until I was 14, 15. Dad was the old type, I guess. You don’t make mistakes, you practice hard or you get the whip, the old razor strap. … When I was 16, I was practicing, made a couple of mistakes and he didn’t like it. I protected myself with the violin and he smashed it to smithereens. From then on, I just quit and went to work in the woods myself.”

Nick also developed a love of bodybuilding, though he tried boxing first, and had wrestled amateur for five years at the Western Sports Centre.

For Jerry, the first sport he excelled at was gymnastics. “I was a gymnast when I was 15, 16. I was first in high bar and second in parallel bars and third all-around,” said Jerry Kozak in the summer of 2011.

Both brothers worked in the woods logging — Nick said he went for two or three months every year from age 16 to 19 — and both brothers developed their physiques on their 5-foot-10 frames.

But Nick was decidedly committed to his physique, and was later Mr. B.C. In 1954 and Mr. YMCA. “I was into weights too at the time. He got involved in that,” said Jerry. “The promoter and some of the wrestlers at the time in Vancouver worked out at the gym we went to. Nick would always be in their ear, be right there watching everything, while I’d just be working out.”

The older brother was the first into pro wrestling, and was a regular at the matches put on by BC promoter Cliff Parker at the Exhibition Gardens in Vancouver. “I used to go every Wednesday night when I could and watch the guys. I knew Cliff because he liked to come down to Western also, and that was his way of working out,” said Nick. “I’d get on the mat with Cliff, who was around 225, 230. We used to push around and he could beat me no problem. I just kept working out and working out. Pretty soon he could beat me, but it wasn’t so easy. Finally, it got so that we would wrestle like crazy and he never could beat me, but I could never beat him. It was just a standoff. All the time I was saying, ‘Cliff, I’d like to be a professional wrestler. It looks pretty good.’ ‘Oh, you’re just a little light, you need to get bigger.’ … Finally, he called me one day. ‘You still interested?’ ‘Yes, sir!’ He said, ‘I need somebody to carry the jackets back to the dressing room. Would you be interested?’ I said, ‘Oh my God, yes. In a heartbeat.'”

From there, Nick started refereeing, and when another wrestler no-showed, it was his time. Nick had not been smartened up that professional wrestling was a work, but his first bout went to a 15-minute draw, done mainly amateur style. “I was trying to go behind him, take him down, ride him, everything else,” said Nick.

All the while, Jerry was trying to gain weight so he could wrestle too, often hitting the road with his buddies to be ringside and cheer his big brother on during the matches.

“At that time, I only weighed about 165 pounds. I could eat two horses and still weigh 165 pounds,” lamented Jerry. Nick gave Jerry a diet to eat to gain weight, and the goal was 185 pounds. Eventually he got there.

By that time, Nick Kozak had made a name for himself in Pacific Northwest bodybuilding competitions, and Cliff Parker arranged a meeting for Nick with Portland, Oregon, promoter Don Owen. Nick wasn’t hired immediately, but did eventually land a gig that started his full-time journey into pro wrestling.

Jerry finally got his break in Tucson, Arizona, where he worked as Jerry Parker (at Nick’s suggestion).

It wasn’t long afterwards that the brothers were in Houston, Texas, though they weren’t promoting themselves as such. It was Houston promoter Morris Sigel who convinced them that they should be a true team.

“Are you guys real brothers?” Sigel asked. “Well, that’s fantastic.”

The publicity train started at that point, said Jerry. “When the writer heard that we were real brothers, boy, he wanted to come over and do a story on us right away. He didn’t let up.”

Though the Kozak brothers worked many territories, they are most associated with Texas.

The late Bull Ramos talked about the Kozaks years ago: “They were good, but they were small and that’s how come they never got the big, big push.”

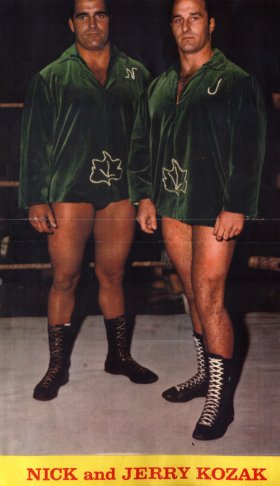

Nick reflected on what made them successful: “Jerry and I both worked out. … You’re up there half-naked, you’d better look pretty good. The fact that we were fast and furious. Jerry did most of the high-flying, tumbling stuff. I did too, but he was a little lighter. We used to do high hand-to-hand handstands, backlifts, stuff like that that not too many guys were doing back then,” he said. “I think we presented ourselves in an athletic way, did our stuff in there and looked good doing it.”

A plumber’s son from Austin, Texas, Virgil Runnels, was decidedly a fan.

“Ah, the Kozaks. I remember them fondly,” said Dusty Rhodes. “They were heroes of mine. I wouldn’t tell them that, but I looked up to them. They kind of helped me out a lot, guiding me along.”

In fact, it was Jerry Kozak, working with a young Rhodes in El Paso, who explained to Rhodes how to take it easy in the ring.

“I didn’t understand the word potato. I got back to the Alamo Plaza Hotel in El Paso, and they’d broken into my room, and I didn’t know it,” recalled Rhodes, laughing at the memories. “I turned back the covers and in the bed, they had taken a sack of potatoes and emptied them all in my bed. So I figured out, I don’t remember who I was talking to, I went to somebody and said, ‘What is a potato mean?’ They told me, ‘It means you’ve got to loosen up a bit.’ Then I had to go to somebody else and find out what loosen up meant.”

Jerry Kozak’s background in gymnastics was something that was promoted — and handy.

“Kozak,” said Joplin, Missouri, promoter Bob Clay in 1963, “can do all the tricks that [Edouard] Carpentier does — the tumbling and the aerial acrobatics — but Kozak is much faster than Carpentier. I know that’s saying a lot, but I’ve seen them both, and I know what I’m talking about.”

The gymnastics lessons translated to wrestling.

“You know how to fall,” said Jerry. “If someone takes you down, and your shoulders are going to the mat, you’re going to break that shoulder or your rotator cuff. You’ve got to know how to fall. You’ve got to pull your arm up so you land on your back or side. That’s things you learn.”

At the end of the 1960s, Jerry Kozak was offered a chance to promote in Amarillo, Texas, for the territory which was owned by the Funks. He was there a couple of years before Dory Funk Sr. died in 1973.

It all came about because of Jerry’s wife, Edie Mae. In talking one day with Stanley Blackburn, who owned a piece of the Funks’ promotion, she mentioned that her and Jerry were thinking about getting into the promotional end of things.

It was news to Jerry.

Nick and Jerry Kozak years ago at a reunion in Seattle, Washington, with Tiger Conway, Sr. Photo by Mike Lano, WReaLano@aol.com

“About a week later, Dory Funk Sr. called me, and he said, ‘Hey, I understand you want to get into promotion.’ It kind of shocked me. I turned around and asked my wife, ‘Did you want to get into promotions?’ She said, ‘Yeah.’ I said, ‘Yeah, what do we need to do?'”

The first event that Jerry Kozak had a hand in was at the new Civic Center in Amarillo, with an NWA championship match between Dory Funk Jr. and Gene Kiniski in the main event. “Boy, the house was packed. They took me up into the ring and introduced me and everything, and told them I was the new promoter,” recalled Jerry. “I went back to my wife and I said, ‘Damn, we’re going to be billionaires shortly.'”

The regular matches were every Thursday at the Sports Arena. The following Thursday was not a repeat of the show at the new arena. “I don’t even think there were 200 people showed up. I looked at her, and she looked at me, and I told her, ‘I think we’re holding the bag.'”

The couple went to work, involving local businesses to distribute tickets and promote the shows. “Slowly, over a couple of years, it just built up and built up and built up,” said Jerry.

And it was decidedly a team effort. “I still wrestled a couple of times each week (while promoting). She had a fantastic business head. She took care of the books. I did the promoting, getting around, talking to people, companies and whatnot. It was a good combination.”

According to Jerry, the Funks had half the promotion, and he and his wife had the other; Dory Funk Sr.’s will upped the Kozaks to 60%.

The Funks, established in Florida, sold their share to Dick Murdoch and Blackjack Mulligan. “They wanted to get rid of all the people that I had seating the people and everything. I told them no. I said, ‘These people are good workers and take care of everybody. We’re not going to get rid of them.'”

That was the beginning of the end, explained Jerry. Murdoch and Mulligan booked a big name who then no showed because of a cold, and they wanted Kozak to tell the people that, to be the bearer of bad news. “Right then, I knew what the hell was happening because they started running a lot of other towns and screwing up royally,” said Kozak.

Then Jerry’s wife got sick — ovarian cancer. “She just kept it a secret from me for so long. Then when I realized what was happening, I almost fell apart. … I ended up putting her in the hospital. She didn’t last but three or four days.” The couple never had children.

“What I’ll never forget is when she passed away, Murdoch and Mulligan told me that we were stealing money. I said, ‘All the books are there. You can look through them, what you got and what we got. I can’t believe you sons-of-bitches come off with that.'”

Jerry sold his portion to a local fan, whose name he couldn’t remember. “I was done with wrestling, period.” The rise of the WWF into a national promotion not long after finished off Amarillo as the centre of a territory.

Widowed, he moved to Houston to be near to his brother Nick, who owned a wrecking business.

“I bought a wrecker and worked with him,” Jerry said. Nick started working with WWF, taking the ring around, and Jerry opted to find new work. He installed refrigerators, stoves, microwaves and other appliances in new homes for about five years.

Jerry survived his own cancer scare a few years back, bladder cancer, but never got to perfect health again. He primarily kept in touch with the wrestling business and his old friends through his brother, Nick, who was always more outgoing and gregarious. They each had a trailer on a single property in Houston.

His passing on March 5, was announced by Nick on the weekend, calling in to the annual wrestlers-only Gulf Coast Reunion in Mobile, Alabama, a favourite trip for Nick every year.

He is survived by his brother, Nick and sister-in-law Judy, sisters Anna and Dolores, brother-in-law Brian and many nieces and nephews. He had two sons, Jim and Rick, from his first marriage with Lorraine.