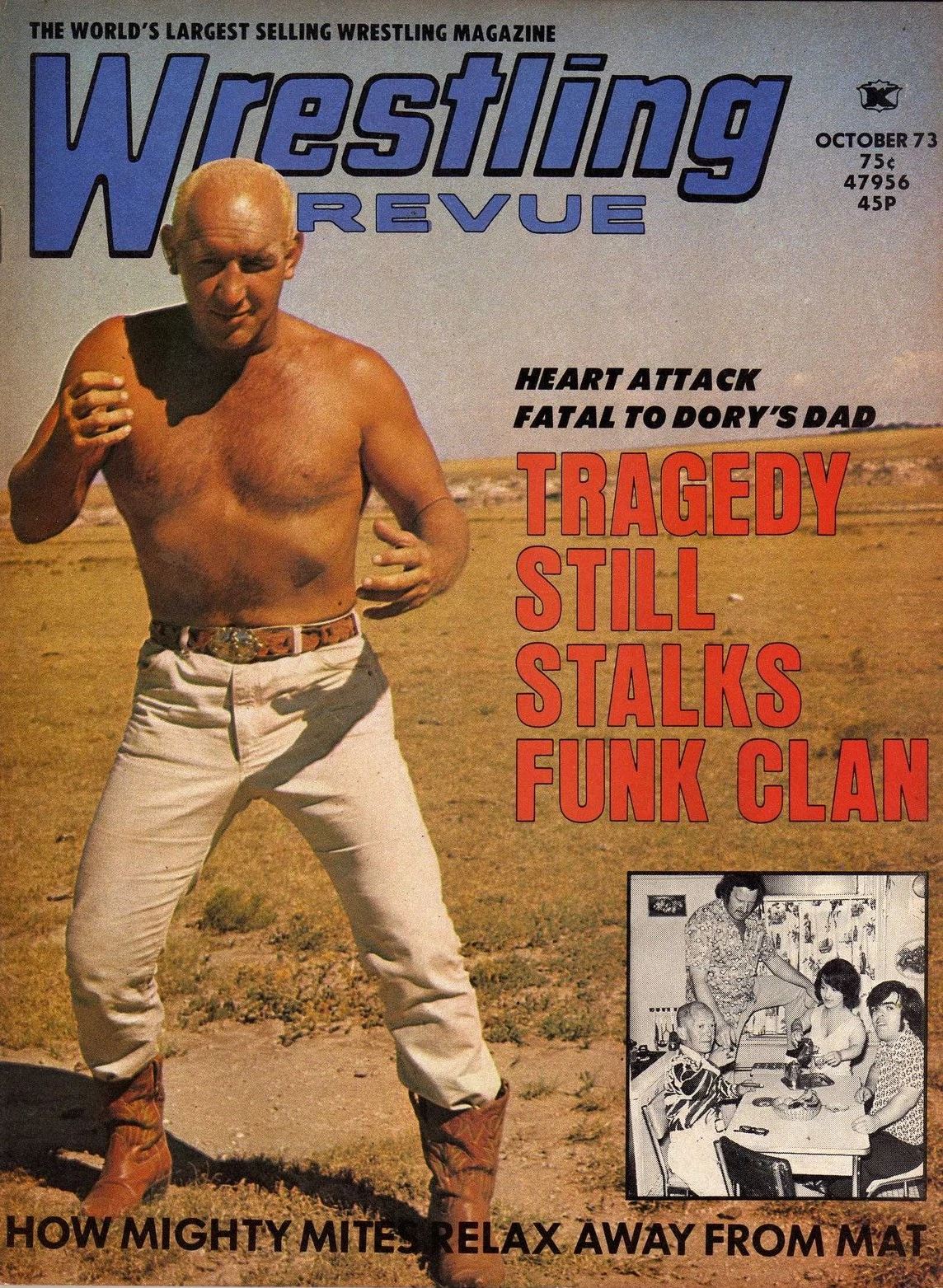

After the matches on June 3, 1973, Dory Funk Sr. had a bunch of his wrestlers over at his Flying Mare Ranch in Umbarger, Texas. After a few drinks, the challenges started. “The old man said, ‘Try to get out of this, fella,'” recalled Les Thornton. “He put a full Nelson on me, so I picked him up and ran him into the fridge, and all the stuff came flying out. We all got caught. He put a bandage on his head. He was a tough old bugger. He just laughed about it.”

Up next was Gord Nelson, a Canadian amateur champion. Nelson said it was a short battle. “He said, ‘I’m getting too old.’ That’s something that he would never say otherwise.” At about 10:30 p.m., Funk suffered a heart attack, and died shortly afterwards at St. Anthony’s Hospital in Amarillo.

“To me, I think he was glad that he went that way,” said Thornton. “That’s what Dory Funk Sr. was like, a tough old bugger.” Or, as Harley Race voiced, “he was tougher than rawhide.”

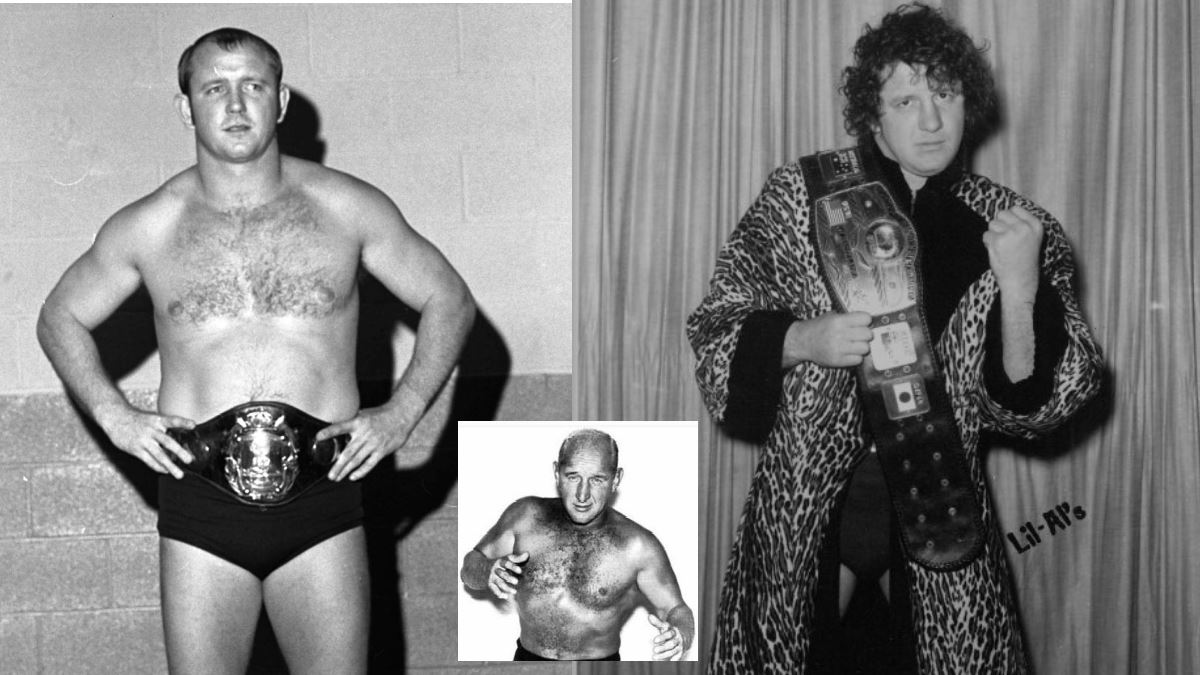

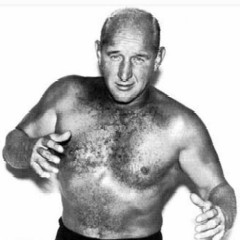

Dory Funk Sr.

It is believed that his last bout was May 31st, where he teamed with his son Dory Jr.

The news shocked his friends.

“Aw, he’s just doing some, more ribbing,” Gory Guerrero, the promoter in El Paso, said that he thought upon hearing the news. “It was a case of over exertion,” Guerrero told Bob Ingram in the El Paso Herald-Post. “He had no history of heart trouble. But I believe he should have slowed down and taken fewer matches or quit altogether. He wrestled at Amarillo the previous Thursday.”

Jerry Kozak, who also promoted some towns for the Funks, was there the night Dory Sr. died. “All of a sudden, it was like, ‘Where the hell is Dory? Where’s Junior and Terry? They’re gone!’ And we couldn’t figure it out. That’s when they took Dory to the hospital. Of course, we found out the next few days that he’d passed away.”

“I was in another room,” said Moose Morowski. “They started wrestling and, I don’t know what it was. Next thing I know, I hear that they called the doctor, ambulance or something. He died at the hospital. It was terrible. Senior, every year, he threw a thing for the guys that wrestled there, he’d throw a barbecue at his ranch, they’d castrate some bulls, have a big barbecue, lots of food, lots of drinks.”

Kozak also made mention of Funk’s eating habits, in this case steak “Dory Sr. was sitting at the head of the table, and I was cutting the fat away from the meat. He said, ‘What are you going to do with that?’ I said, ‘Well, I’m not going to eat it.’ He said, ‘Well, give it here.’ I said, ‘Daggum, Dory, you eat it, all that fat is going to kill you!’ And it surely did. … He didn’t die then.”

Born in 1919 in Hammond, Indiana, Dorrance Wilhelm Funk was an Indiana state high school wrestling champion for three years and Amateur Athletic Union champion for a year. In 1939, he married his high school sweetheart, Dorothy, and entered Indiana University, where he competed on the wrestling squad and was selected to the school’s Amateur Wrestling Hall of Fame. Following a stint in the U.S. Navy, stationed primarily in the Philippines during World War II, he turned to professional wrestling.

In the early days, he worked as Dory Dean. “Dean (Funk), a Hoosier and student of Billy Thom, famous Indiana wrestling coach, showed the big crowd what he had gained in tutelage from his coach as he used a leg Nelson to good advantage all through the bout. He won the first fall with that hold and threatened in the second fall with the same punishment but Marty reversed and gained the setto with a Boston crab. With less than two minutes left in the fracas, referee Curley Conley called the match a draw,” reads a report in the Portsmouth (Ohio) Times, on April 20, 1948.

Dorothy and Dory had two sons who would follow in his footsteps, Dory Jr. (in 1941), and Terry (in 1944), both of whom would later become NWA World champions. Their three other children were Bobby and Dony, and daughter, Doree. Like most wrestlers of the day, it was a nomadic lifestyle, traveling together as a family in a 30-foot trailer. “Every time you’d move, you’d see some people you had been friends with,” said Dorothy in 1999. “Each place you’d move to, it was like going home to see your friends.” A favorite promotion through the years for the Funks was summertime-only Northern Ontario territory, run by Larry Kasaboski, where the hunting and fishing was excellent, and the off-duty lumberjacks lusted for hardcore action.

In 1949 he moved to Amarillo, and from then on, he would forever be associated with West Texas, even while continuing to appear across the continent. “I was just too tough for these tough Texans, so they just adopted me,” Funk quipped in 1953. The 6-foot, 205-pounder electrified crowds with his determination, his unique style (brawling with a touch of jiu-jitsu from his war-time experiences), and his willingness to shed blood on their behalf.

He became king of the Texas Death Match, and it wasn’t uncommon for feuds to build up to the point where the matches would go for hours.

“Funk was a tough wrestler,” said Bob Geigel, a contemporary. “If a spectator wanted to wrestle, Funk would crack them. He’d get them in the ring and work on them.”

Funk’s trademark move was the spinning toe hold. “Just as Dory would cream an opponent with a left hook, the victim would fall and thrust his leg upward where Dory could grab it. Then Dory would put it next to his chest, grip it firmly, then take four or live trips around the victim’s body,” a newspaper story described in 1963.

“Everywhere Senior went, he was a hero,” said Morowski. “Anybody who knew him and remembers him from day one, they all respected him all the time.”

That high stature came from more than just pulling in the crowds, both from his days as an independent, and, in 1955, when he partnered with Karl “Doc” Sarpolis to buy out Dory Detton for the rights to the Amarillo territory and all of West Texas.

A newspaper clipping from Abilene, Texas.

“My father was so creative,” Terry Funk said. “He never wrestled the same match. His influence is still felt today. He always said, ‘If we are taking from the community, we have to give something back.'” Having spent three years as the superintendent at Cal Farley’s Boys Ranch, where he started a wrestling program as well, Funk Sr. gave 10% of the profits of each show he had to the Texas Boys’ Ranch.

In his obituary, Funk’s association with Farley was mentioned. “Funk agreed to ‘help out’ at Boys Ranch for a period of three months in 1950. But, Funk wound up remaining at Boys Ranch for three years as superintendent. As a sidelight, Funk continued his ranching and cattle raising work. He always kept abreast of the needs of the boys at Boys Ranch and other children in the area.”

As his sons began pro wrestling as well, Funk Sr. became a master politician, all the while respected as one of the most honest, fun-loving promoters in the business. Nick Bockwinkel was offered a chance to come to Amarillo, but knew his role, and recalled telling Dory how he saw things. “First of all, there’s the number one babyface, Dory Funk Sr., then the number two babyface is Dory Funk Jr., and the number three babyface is Terry Funk. Then you’ve got your fourth son, Ricky Romero. But now you’re going to bring in, from Hollywood, this blond, nice-looking, All-American boy by the name of Nick Bockwinkel into Amarillo. And you expect me to get over?”

Working the backrooms of the National Wrestling Alliance, Funk Sr. angled for his oldest son, Dory Jr., to win the coveted world title in 1969. (Funk Sr. had been NWA World Junior Heavyweight champion for a month in 1958.) The notoriety helped boost the Funk name nationally, so Senior hit the road some more with his sons. After a bout with Terry in New York’s Madison Square Garden in 1972, he did admit that there was always a siren calling him home. “I love Texas and it’s kind of hard to stay away from a loved one for long,” he chuckled.

Funeral services for Funk Sr. were held on June 5, 1973, at the First Methodist Church of Canyon. He was buried in the City of Canyon cemetery.

RELATED LINK

This piece was originally going to run in The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: Heroes & Icons (written by Steven Johnson, Greg Oliver and Mike Mooneyham), but was cut for space purposes.