EDITOR’S NOTE: A great wrestling match is like a great meal. You can have all the essential ingredients, in the case of the squared circle this would be a well-promoted event, talented wrestlers and an enthusiastic crowd, but just as spices enhance a dish, quality color commentary is needed alongside a match to keep everything from being bland. In the following feature, Mike Lano toasts the memory of his good friend and colleague, Los Angeles announcer Miguel Alonso, who also was one of the WWE’s first Hispanic play-by-play men.

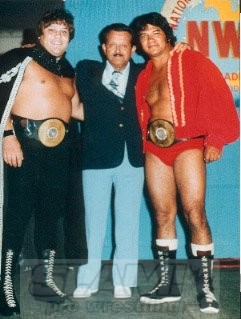

Miguel Alonso, center, with Raul Mata and Chavo Guerrero on the set of the Los Angeles wrestling show. Photos by Mike Lano, WReaLano@aol.com

From 1970 until December of 1982, Miguel Alonso was our Los Angeles territory’s nationally syndicated Hispanic show play-by-play announcer before promoter Mike Lebell closed/sold our territory to the World Wrestling Federation. I was one of the program’s ringside photographers. With Alonso’s passing in April, I found myself reflective over the history of the territory.

In late 1969, Lebell either lost Channel 5 KTLA (what many considered to be our strongest non-affiliate station at the time with the most clout) or got a better price to move the show to a one-hour Saturday night slot hosted by Dick Lane, a former major movie and television actor from the ’40s, to the smaller Channel 13 KCOP. This channel was viewed as the one with the least money and clout, but on the plus side, the powers that be there agreed to permanently house a wrestling ring. It was, at the time, a better deal all around, allowing more plugs for every other Friday shows, house shows, and even sponsorship deals.

It was around this time that it was decided to fill the void of the classic Wednesday night show taped at the Olympic Auditorium with one geared towards the Hispanic audience demographic that Lebell was trying to attract. News anchor Nono Arsu began calling the show with longtime boxing announcing great Luis Magana, but Arsu was soon dropped and Miguel Alonso was brought aboard in early 1970. Alonso had previous experience calling sports including soccer and boxing. He was also the first Spanish announcer for the Dodgers baseball team when they initially came to L.A. from Brooklyn, NY in 1958. The show became the 90-minute Wrestling from the Olympic which was eventually changed to simply Lucha Libre.

Lucha Libre aired locally in Southern California on top Hispanic Channel 34 KMEX, which soon became the syndicated cornerstone of the Spanish International Network (SIN) which would air various programs like the 90-minute wrestling show along its syndicated affiliate route, which included San Francisco, New York, Boston and Miami.

Alonso would speak Spanish to help get the Hispanic names over, but he also spoke English on-air only when interviewing the American or non-Hispanic boys. Some heels like Abdullah Farouk (Ernie Roth) would play gentle ribs with Alonso’s English on the show, but Alonso never failed to stand up to them.

Big changes came in June of 1975 when KCOP kicked Lebell off Channel 13. Dick Lane quit over money in late ’74 and was replaced by Gene Lebell, Mike’s older brother. Alonso and Magana were thus given more opportunity to perfect their on-air interview skills with talent including Freddie Blassie, John Tolos, The Destroyer (Dick Beyer), Bearcat Wright, Ernie Ladd, The Sheik and Ernie Roth.

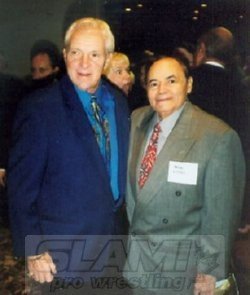

Bobby Heenan and Miguel Alonso.

Alonso was perfect for the interview role since in his own words, he wasn’t very tall. “I made the boys look like monsters,” Alonso once told me. “Sometimes they would play ribs on me by standing on my toes during their promos, waiting for me to shout or say something on-camera. But I never did. Black Gordman and Great Goliath did that a number of times.”

Having worked extensively with Alonso, Gene Lebell shared his thoughts: “Anyone that knows Miguel loves and respects him and I’m one of many. The best of all worlds to him.”

In 1985, Alonso became the WWE’s first Hispanic weekly play-by-play announcer alongside Pedro Morales. After working for the WWE for almost a decade, the time came that WWE CEO Vince McMahon called to let Alonso know he was letting him go.

Alonso had an inkling he and Morales were going to be fired, so just as McMahon called, starting off, “Miguel, things are changing and we’ve decided to go in a….” Miguel interrupted and said, “Vince, hang on a few minutes. I was just going to make myself a martini when you called.”

Miguel intentionally took five minutes to make the drink and take a few sips before coming back to the phone. When he did, he was surprised that McMahon had stayed on hold that long. Alonso assumed he might delay things and that McMahon would just hang up on him. Once back on the phone, McMahon immediately continued, “We’ve decided to go in a different direction and are letting you and Pedro go. We’re bringing in some younger guys, one to play heel, one face…”

Alonso loved to tell this story and prided himself on being one of the very few people to put McMahon on hold — and have McMahon actually there when he finally came back to the phone.

“I was one of the few who ever dared keep Vince waiting, knowing what news was coming and not really wanting to deal with it,” Alonso once said. “I handled it my way at least.”

Luis Magana, Miguel Alonso and Jimmy Lennon Sr.

About a year later, in 1994, Alonso and Morales were hired to do similar duties for World Championship Wrestling (WCW). I have fond memories of driving Alonso, Morales and Gene Okerlund at times from the hotel to WWE and WCW’s venues and Alonso would always tell great road stories about Blassie, Gordman and Goliath.

Alonso was undoubtedly one of the nicest people I’ve ever met in wrestling and boxing.

Replacing Alonso in WWE was Puerto Rico’s Hugo Savinovitch who unlike Alonso would take on-air sides and was a lot more animated than he was. “But too over the top,” Alonso would often remark.

Alonso prided himself on his straight-shooter calling style and had many memorable catch phrases including “uno, dos TRES PALMADAS!!!” (in English: one, two, three applause) when someone got pinned. He is also credited with inventing a term still used by Hispanic announcers today: “una chiaso” for chair shot. And the high lilt in his voice when he said any of his trademark phrases was certainly memorable. Alonso admired his colleague Dick Lane and gave him credit for helping him hone his craft. “I idolized Dick Lane so much because he added believability that this was actually a ‘sport.’ He was a legend and I learned a lot from him as a teacher,” Alonso said.

Up until about two years ago, Alonso was still mentoring and advising several Hispanic media sites, television and radio stations and newspapers. He was viewed by many as a legend in the Hispanic community. He kept in touch with many of his friends in the wrestling community, but he felt his best wrestler friends were his announce partner Luis Magana, John Tolos and Mil Mascaras, who he kept in touch with; Alonso was so proud that Mascaras was going into the WWE’s Hall of Fame this past April at Wrestlemania 28. Like many of us, the passing of friends such as Bull Ramos and Gordman and Goliath hurt Alonso, and he often shared his recollections with Carlos Mata, Gene Lebell, L.A. publicist Jeff Walton, and the Guerrero Family.

Miguel Alonso and George Steele.

In late 2011, Alonso was in a car accident when his wife was driving him to the pharmacy and the couple was rear-ended. The accident worsened an already damaged and weak heart. Doctors advised that Alonso needed two heart valves replaced but that no doctor in the U.S. would perform such cardiac surgery on someone of his age and condition. The family told me they found a U.S.-trained and certified surgeon in Tijuana who claimed he had great success with the elderly and that many had their lives extended five to 10 years. The Tijuana doctor agreed to perform the surgery on the condition that he was paid $30,000 in cash because Alonso’s Medicare and insurance would not pay for the risky procedure being done outside the U.S. After the surgery, the doctor told the family that Alonso had pulled out fine after the first of two induced comas. When he got back to the San Diego area, his American doctors felt Alonso’s heart was beating too strongly for his other organs and that his lungs were filled with fluid. Alonso quickly developed liver cirrhosis, and his kidney had begun failing. The doctors were concerned his heart was beating so strongly that he might have a heart attack.

I remember Alonso being pretty frail when I saw him last September. Alonso was in and out of hospitals in Mexico and near San Diego and by December, his doctors weren’t giving him long to live.

Having been charged with setting up a reunion of talent from the Los Angeles territory for January’s WrestleReunion, I kept up on the news and wanted Alonso there.

His primary doctor told me, “He can either deteriorate in his hospital bed, or go to the reunion which will most likely up his spirits and will to live, being around his friends and those who love him. That would certainly be my choice if he’s up for it.” His wife Margarita and secretary then brought him on to my reunion on January 27, 2012.

Miguel Alonso acknowledges his ovation at the Los Angeles territory reunion in January 2012.

Alonso was wheelchair bound at that point, the result of breaking his hip in 2007. He received a standing ovation from the room when he arrived. I went over and made sure he was the first to speak, since I wasn’t sure how much energy he’d have, but he talked for several minutes, then broke down, saying he knew this was the last time he’d see so many of his friends like Jesse Hernandez, the Torres family, Mando Guerrero, Dick Beyer, Gene, Jeff Walton, Art Williams from the office, and all the boys like Jack Armstrong, Superstar Billy Graham, Ric Draisin, Billy Rogers, and more. Alonso also talked about his immediate friendship with Mascaras who he’d kept up with. He also mentioned his friendship with Bobby Heenan, who he last saw at Cauliflower Alley Club reunion, and the late John Tolos, who he missed terribly.

The last time I talked to Miguel on the phone he was kind of out of it due to all the various medicines they had him on, but later that day he called me while watching some Hispanic TV show called Eccentrics, a Spanish program comparable to Ripley’s Believe it or Not, which Alonso loved.

On April 6th, the doctors advised the family that Alonso had no life left inside and was most likely in agony. The decision was made to take him off his respirator at 8 p.m. to give his daughter enough time to come in to say goodbye to him as she lived in Tucson and had to fly in. The time was 7:08 p.m. when he passed away on his own at age 89.

He was survived by his wife Margarita, son Miguel Alonso Jr, daughter Martha and his nephew Ernesto Padron.

I am honored that he was a part of my life for so long.