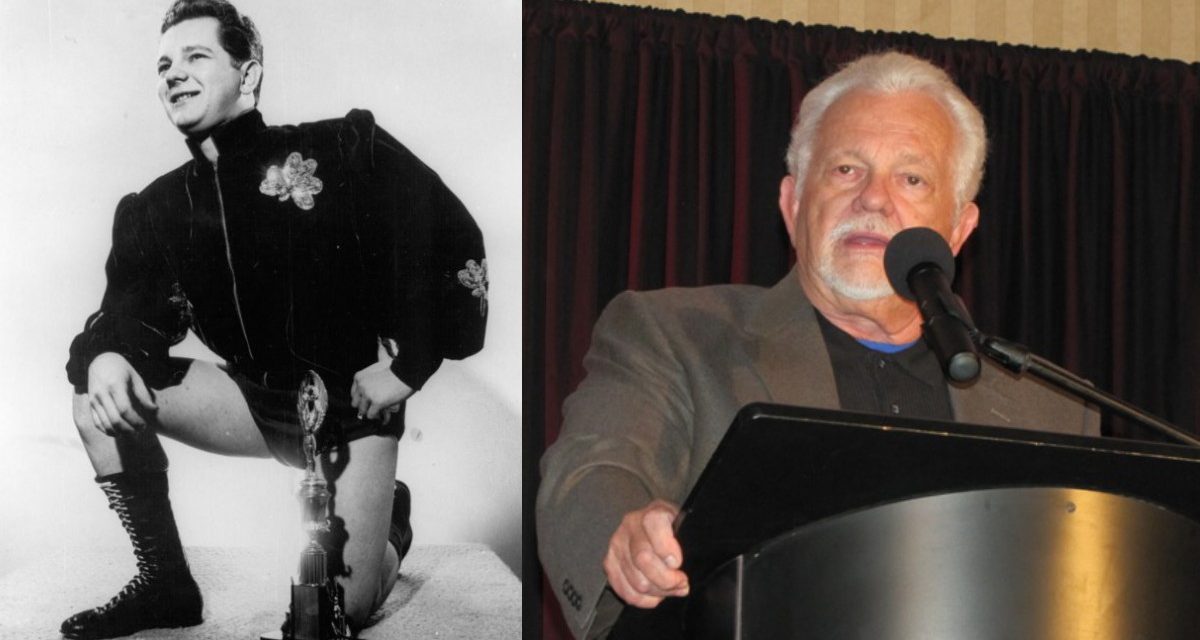

Before Les Thatcher donned a sport coat and butterfly collar to call action from behind the host desk at Southeastern Championship Wrestling, the wrestler-turned-commentator squared off with — and rode the highways alongside — many of the innovative Knoxville, Tenn., territory’s stars. That rough and tumble version of on-the-job training helped establish Thatcher, who began his wrestling career in 1960, as one of the most trustworthy announcers of the ’70s and ’80s, especially in the eyes of the east Tennessee territory’s fans.

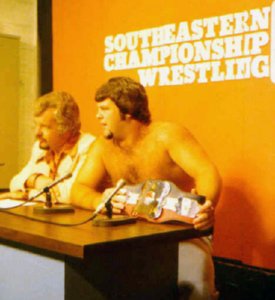

Les Thatcher at the announcer’s desk with Jerry Lawler in Southeastern Championship Wrestling. Photos courtesy Southeastern Championship Wrestling tribute site on Facebook

“I had avoided Tennessee for a lot of years because of the saga of Nick Gulas,” says Thatcher with a laugh. “I was looking to get out of Charlotte around 1968. So, when Ken Lucas and Dennis Hall went in there and did OK, I thought I could, too.”

Already an established wrestler, Thatcher got his feet wet in announcing before he first came to Knoxville to work for promoter John Cazana in ’68. Like his friend and fellow pro wrestling scholar, Gordon Solie, Thatcher had a history in drag racing, both behind the wheel and in the announcer’s booth. Longtime Canadian fans probably remember him best as a commentator for Rudy Kay’s Maritimes promotion during the early ’70s. After a year working for Kay, Thatcher moved south and eventually landed in the Crockett family’s Charlotte, NC, territory. He credits midget grappler Lord Littlebrook for helping him to traverse to the “Wide World Wrestling” announcing table by putting in a good word with Jim Crockett, Sr.

“I’d always been intrigued with broadcasting and had done some track announcing. I was also fascinated with Wolfman Jack and wild disc jockeys like him,” remembers Thatcher. “It really perked my interest when I went to Tampa in 1967 and saw Gordon Solie. Before him, a lot of the announcers were local TV weathermen or the kiddie show host and they didn’t really take wrestling seriously. But, after seeing Solie, it struck me as something I wanted to try.”

At the same time he appeared on camera as a host in Charlotte and later Knoxville, Thatcher was still an active wrestler. A perpetual babyface often paired with tag team partners like Nelson Royal and Whitey Caldwell, he remembers how the weekly travel schedule left little room for diversion.

“I wore both hats — broadcasting and wrestling, in the ring and in the office, for two territories at the same time. From 1974 to 1977 my life was similar to this: Mondays I’d go to the Charlotte office. George Scott and I would sit down and make up cue sheets for interviews for all the outlets and I’d wrestle somewhere Monday and Tuesday night. Wednesday morning, I’d go to Raleigh where we’d do about 125 promos in an afternoon. Then, back to Charlotte to wrestle somewhere on Thursday. Friday morning, I’d get on a plane and fly to Knoxville where Ron Fuller would pick me up at the airport. We’d go to his house to write the TV and do formats. I’d wrestle somewhere there on Friday night, do the Knoxville TV Saturday morning and then wrestle Saturday night. Then, it was back on the plane Sunday for Charlotte. I repeated that cycle for three years. I’d pass myself in the air sometimes!”

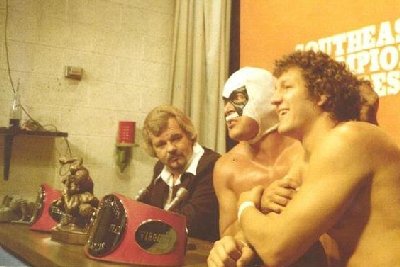

Les Thatcher listens to Ronnie Garvin (under a mask) and Bob Orton Jr.

Ron Fuller’s purchase of the Knoxville promotion in 1974 gave Thatcher a new creative outlet with which to work. Today, he looks back fondly on the short leash working for Fuller, billed as the Tennessee Stud, allowed him. Although wrestling TV was generally unscripted back then, Thatcher can’t help but chuckle about finding out how off-the-cuff the hour-long show Fuller asked him to produce and host actually was.

“Ron and I went to lunch and went back to his house. We sat down at his dining room table and I said, ‘Let me see the formats for the TV show.’ Only thing was, he didn’t have a format at all! Cazana had never used formats all the years he did television at channel 26. He just winged it. Of course, they did a rotation of the matches, but nothing else like cues or interviews were ever timed. You just went out there and free-formed. Later, when I started passing out formats for the to the director and the soundman at channel 26, they looked at me like I was crazy. As long as they’d been doing one, they’d never seen a format for a wrestling show.”

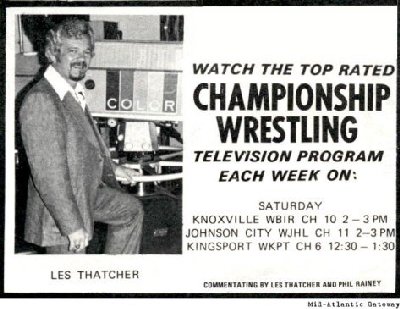

First shot in Knoxville’s channel 26 and later channel 10 TV studios, Thatcher developed Southeastern Championship Wrestling into one of the sharpest looking and most concise wrestling shows of its time. Kicking off with an animated graphic of the spiraling Southeastern “grapplers” logo, its brightly lit, orange and red-splashed set brought a look to the Saturday afternoon program that resembled a six o’clock newscast. Though only available to viewers in the east Tennessee and south Kentucky area, it was an innovative program on which many future staples of other wrestling TVs first originated.

One of those, remembers Thatcher, was the “personality profile.” World Class Championship Wrestling is often credited for spearheading the sit-down, behind-the-scenes interview segments in which host and wrestler conversed about life outside the ring. Thatcher was bringing the same premise to Tennessee fans several years earlier. “Red Bastien had told me, God love him, that you can’t do a low-key sit down interview in the middle of a wrestling show. He said, ‘It’ll kill your momentum,'” Thatcher recalls. “Later on, after we’d started doing the profiles, Red actually called me and asked if they could use the same concept out in Frisco where he was working for (Roy) Shire!”

Thatcher says the segments were inspired by a similar format used in pro football telecasts. “Back in the late ’60s and early ’70s, during halftime, the NFL would do something similar that really caught my fancy. They’d show some big, nasty defensive lineman, for instance, making pottery. It was the other side of the coin. Even back then, I used to question some things about our business. It was kayfabe, obviously. But I wondered if the fans really did fully believe that the heels went home and beat their wives up or kicked the dog around! There was somebody even Al Capone loved, right? He didn’t shoot everybody he saw.”

Thatcher recalls how his friendship with “Bullet” Bob Armstrong, one of the Tennessee/Alabama/Kentucky region’s most beloved performers, inspired one of the show’s most well-received profile segments. “Bob was a good friend of mine and both of us liked old doo-wop music. To kill time in the car going from town to town, we’d play a game where I’d give him the name of a song and he’d have to give me the artist and the label. We’d play till one of us stumped the other guy,” says Thatcher. “The first personality profile I did with Bob, I said, ‘Remember that game we used to play going up and down the road?’ And he said, ‘Yeh, you know the one I used to beat you at all the time?’ So we did just that — he’d give me a song and I’d give him the artist and vice versa, back and forth, till we wrapped the segment up.”

That segment, in particular, confirmed to Thatcher how strongly the personality profiles were resonating with the show’s diehard audience. “A couple of weeks later, I was standing outside the Knoxville Coliseum and this lady walked up to me. She said she was the secretary to a big department head professor at the University of Tennessee who watched the show and was also a big fan of rock ‘n’ roll history. She said, ‘He heard you and Mr. Armstrong talking on TV and wondered if it was just part of the show or if you two legitimately knew about that (music).’ I told her we were both big fans and we each had quite a nice record collection. Then, she pulled out an envelope that held a quiz for each of us — two typewritten pages about old doo-wop groups that this professor wanted us to answer then mail back to him. There, again, there was a link with the public. That’s why I felt the personality profile would be so strong for us and it was.”

Another example of how Southeastern Championship TV was innovative can be credited to the program’s set. The professional channel 10 studio environment allowed Thatcher to utilize a ’70s precursor to green screens commonly used by television weathermen. “The set was actually motorized and it had three sides,” he confirms. “One side was chroma-key blue. One side had the big SE logo and the third had big pictures and frames, along with a small SE logo. I had a foot pedal (and could switch between them). As I was saying, ‘Let’s take a look at what happened at the Coliseum last night,’ I would kick that foot pedal and the set would revolve and put the big picture up behind me. We could also do split screens where you saw what guys were doing on different sides of the ring. Nobody else (in wrestling) was doing things like that.”

You know you are important to the promotion when you are in the newspaper ads. Courtesy MidAtlanticGateway.com

The Fuller family shared the wrestling hotbed of Tennessee with other promoters including Nick Gulas in Nashville and, later, Jerry Jarrett in Memphis. Still, the Southeastern leg was able to retain the services several established and future wrestling legends, as well as an outstanding array of homegrown talent. During his time there, Thatcher worked with some of wrestling’s preeminent heels including “Cowboy” Bob Orton Jr., Professor Toru Tanaka, Mr. Fuji, The Mongolian Stomper (Archie Gouldie), Boris Malenko and “Great Mephisto” Frankie Cain, as well as such Southern-fried fan favorites as Armstrong, Ken Lucas, Jimmy Golden, Jerry Stubbs, Nelson Royal and Fuller’s brother, Robert (the future Col. Robert Parker). “We had a hell of a crew of guys come through there,” Thatcher says. “The whole idea was to sell wrestling and I think that’s what we did. We had some blood and guts and stuff like that, but we built things right. When that territory was hot, we were home every night and never had to stay in a motel. The longest trip was 125 miles.”

He also saw several future stars — including Hulk Hogan (then wrestling in his rookie year as “Sterling Golden”) and Randy Savage — cut their teeth and take their lumps on the Knoxville circuit. “There was one guy who we had the opportunity to use, but couldn’t because we were full-up and had a waiting list,” he remembers about one future Hall-of-Famer who got away. “Leo Garibaldi, out in L.A., called me one day and said he had a kid who wasn’t the greatest worker in the world but had great charisma and could really talk his butt off. I talked about it with Ron and, again, we had guys on a waiting list and didn’t see fit to move anybody. I called Leo back and told him I’d love to help out, but we couldn’t right now. So, that’s how Crockett ended up getting Roddy Piper!”

Looking back on his time behind the mic, Thatcher says he was more of an “analyst” than a “color commentator.” His calm, unhurried way of communicating the ins and outs of program angles to the fans was a direct parallel to the excited mannerisms of Joey Styles, Michael Cole or Jerry Lawler that became prevalent in the 2000s. More in the vein of Jim Ross or “Dean of Wrestling Announcers” Solie, Thatcher was able to establish a relationship with the fans because they trusted him. If Thatcher said a hard kick by the fearsome Stomper knocked Ronnie Garvin’s jawbone loose, fans believed he meant it.

“I always tried to give teeth and substance to what was going on. Not just, ‘He punched him, he kicked him.’ I tell a lot of these younger independent guys who want to be commentators how these companies who advertised on the old Johnny Carson show wanted Johnny to do their commercials because people who watched that show believed in Johnny Carson.”

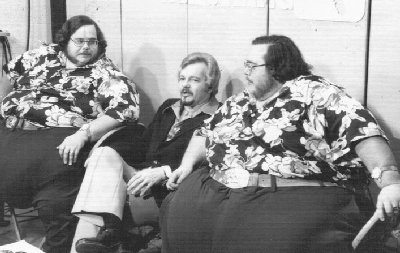

Les Thatcher is sandwiched between the McGuire twins.

Again, the believability Thatcher espoused as a broadcaster can be traced directly back to his time as a wrestler — a clean-cut, blond babyface who baited the heels in the ring, as well as the fans in the seats. Sometimes that believability turned out to be a hindrance, as it did one night in Morristown, Tenn. There, on a card at the hometown ballpark, Thatcher was brawling in a tag match with one of the Southeastern area’s best talkers — the wily, bare-knuckled “King of Kingsport” Ron Wright, whose hot-tempered interview style Thatcher likens to a fire and brimstone Baptist preacher.

“I wouldn’t say Ron was a great worker, but he was a hell of a heel. Just a fist-punching, ass-kicking heel that could cut a hell of a promo. He’s got a scar that runs from his waist all the way up his back. That’s how serious a heel he was. That night, in Morristown, both Ron and I were throwing punches under the ring, which didn’t have an apron on it. He took a roll of adhesive tape out of his trunks and was going to tape me to the ring support. About the time he started wrapping the tape around one of the braces, I saw Ron look over my shoulder and his eyes got real big and he said, ‘Oh, Christ!’ He didn’t turn around and get out of the ring, he slid out backwards. Then, in my peripheral vision, I see coming up on my right side a fan with a big damned Hawkbill knife in his hand. He was gonna save me and probably would’ve ended up slicing my wrists trying to get the tape off! That’s the kind of heat Ron, and his brother, Don, got.”

As the ’80s dawned, Fuller sold the Tennessee leg of the Southeastern territory to Jim Barnett and began concentrating on the Gulf Coast area of Mobile, Ala., and Pensacola, Fla., where the Continental promotion later thrived. Barnett soon sold it to Crockett, who helped facilitate the short-lived Southern Championship Wrestling run by Crockett, Ric Flair and Blackjack Mulligan for which Thatcher was called back to host. After that short-lived venture came to an end, Thatcher spent the next couple of years as a broadcaster-for-hire doing voice-overs in Puerto Rico for WWC shows that were broadcast in English. When Southeastern TV eventually went back on the air in 1984, Charlie Platt had assumed host duties for the program.

“I did a lot of freelancing for some of the smaller promotions during that time,” confirms Thatcher. “I worked for Ann Gunkel in Georgia and did Mario Savoldi’s TV up in New England. I also worked for a bodybuilding firm that trained bodybuilders and did some competing myself.”

That wasn’t the last Southern fans would see of Thatcher the trustworthy play-by-play man, though. Almost 10 years after leaving Knoxville, he was called upon by buddy Jim Cornette to once again travel south. Cornette, who had recently formed the Knoxville-based Smokey Mountain Wrestling, wanted the trusted announcer to co-host the promotion’s TV broadcasts.

Smokey Mountain gave Thatcher an opportunity to reconnect with commentator Bob Caudle, who he worked alongside in the Crockett territory, and Dutch Mantell, one of many wrestlers who competed in Knoxville. Thatcher says that one of his best Smokey Mountain memories was working alongside Jim Ross for the first time (just a few months after J.R.’s infamous 1994 dismissal from the WWF) as hosts of the promotion’s first Night of Legends supercard.

Longtime wrestling fans in the east Tennessee and lower Kentucky area remembered Thatcher and still trusted him. After all, an old-school fan couldn’t ask for a more trustworthy team of commentators than Thatcher and Ross. “Jim Ross and I had never worked together before that Night of Legends show. We didn’t have somebody in our ear telling us what to do — we just free formed it and played it by ear,” Thatcher says. “During the intermission, Terry Funk came up to me and said that he’d been watching the show on the monitor back there and that Jim and I were calling wrestling the way it ought to be called. When he asked me how long Jim and I had been working together, I looked down at my watch and told him, ‘About an hour and a half.”

By the time Thatcher had settled into his new broadcasting role, it wouldn’t be long until Smokey Mountain folded. Still, he has fond memories of the year spent in Cornette’s old-school revival territory where, in 1994, Thatcher was named the first inductee into the company’s fledgling Hall of Fame. “Smokey Mountain was a fun, old-school territory,” Thatcher said. “There was nothing scripted. You just put it together as you went.”

Les Thatcher, right, with Percy Pringle III / Paul Bearer and “Moondog” Ed Moretti at the 2012 Cauliflower Alley Club reunion in Las Vegas. Photo by Wayne Palmer.

Today, Thatcher, age 71, resides in his hometown of Cincinnati, Ohio. Though he can no longer be found wearing a pair of tights or behind a microphone, he still has a strong connection with the wrestling world. He hosts regular training seminars and has helped coach such young talents as Ring of Honor and/or NWA personalities Eddie Edwards, Adam Cole, Davey Richards and Nigel McGuinness. He co-hosts three Internet wrestling talk shows including “Ringside Rap,” on the Georgia Wrestling History webpage, and “Doc Young’s Wrestling Weekly,” which can be heard on the Wrestling Observer Figure Four Online site.

“I’ll tell ya, I broke into the business in 1960 and since then, I’ve been blessed to work with some of the very greatest wrestlers and announcers in the business,” he says.

Thatcher will also be inducted in the NWA Wrestling Legends Hall of Heroes in August 2012 in Charlotte, NC, a part of the NWA Wrestling Legends fan fest.

Aside from his in-ring training seminars, Thatcher’s coaching might also be of use to some of today’s overzealous commentators. Relying on another page torn from his life as a wrestler, Thatcher — the commentator — always had a keen grasp of when, and when not, to sell.

“Back then, you couldn’t be jolly and entertaining. You sold it as a shoot. The first thing you had to sell was yourself and you had to make the audience believe you,” he says. “That’s what Ross did and what Caudle, Gordon and Lance Russell did. It’s also what Michael Cole or Jerry Lawler don’t do. Everything gets oversold. ‘This is so great that so-and-so is coming out!’ Aw, come on! I love Jerry Lawler but, for chrissakes, he’s 60 years old and we’re supposed to believe he’s never seen cleavage?! The first time I called a match in Raleigh with Bob Caudle, I remember going backstage and Gary Hart telling me how (he liked) me not trying to get myself over. You have to elaborate, yes, but it needs to be within sane limits. You have to convince people you’re honest and true. But, still, it all goes back to selling the product that’s in the ring.”

RELATED LINK