Thump! New book restores Junkyard Dog’s legacy

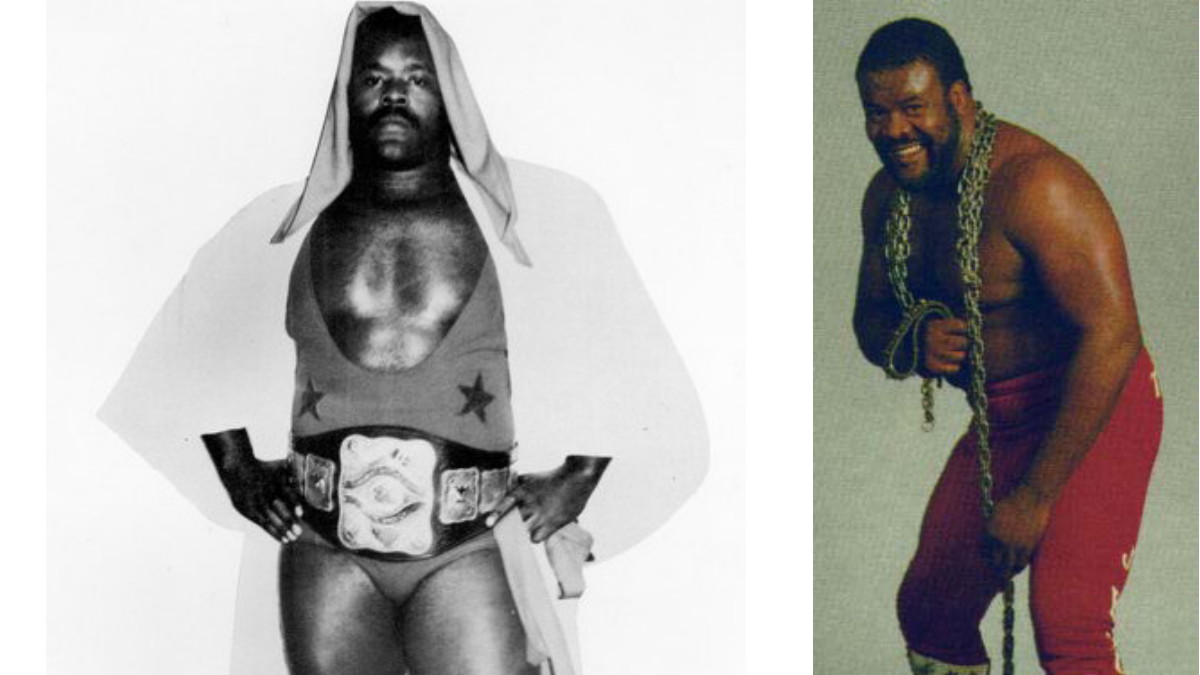

When most wrestling fans think of the Junkyard Dog, they think of the smiling, howling character who danced in the ring with children after his WWF matches.

What many fans don’t realize is that JYD was a pioneer and legend in New Orleans, where he blazed a trail as the first black star in a predominantly white — and often racist — business.

In the new book The King of New Orleans: How the Junkyard Dog Became Professional Wrestling’s First Black Superstar (ECW Press), author Greg Klein writes: “The Junkyard Dog is a forgotten hero, both in New Orleans where he was once king, and throughout the Deep South where his superhero push defied conventional wisdom and perhaps even common sense. His decline in wrestling after leaving Mid South in 1984 and his untimely death in a 1998 car accident have taken him away from us, not just in body, but in spirit too.”

Klein’s biography aims to restore the Junkyard Dog’s rightful place in history by shedding light on his memorable feuds, his rise to superstardom, and his life outside the ring. The King of New Orleans tells the fascinating tale of how the Deep South — a hotbed of racial intolerance — became the home of wrestling’s most adored African-American idol in the ’80s.

“New Orleans was once one of the hottest cities for pro wrestling because of one man — Sylvester Ritter, better known as the Junkyard Dog. JYD became a legend in the Big Easy, drawing huge crowds to the Superdome, a feat no other wrestler ever came close to,” writes Klein. “In 1980, he managed to break one of the final color barriers in the sport by becoming the first black wrestler to be made the undisputed top star of his promotion.”

In the introduction, Klein tells the backstory of New Orleans as one of the biggest hubs of the slave trade of the 17th and 18th centuries, with its share of Jim Crow-era abuses which included hangings, lynchings and Ku Klux Klan atrocities. From the civil rights marches and protests of the ’50 and ’60s to racial issues around black American Football League (AFL) players, Klein provides context before delving into the indelible impact that wrestling promoter “Cowboy” Bill Watts made on the career of the Junkyard Dog.

“In many ways, it was the success of black athletes in football and other sports that convinced Watts that he needed black wrestling stars,” writes Klein. “Pro wrestling always had a code of protecting the business — a code sometimes called kayfabe — and promoters and wrestlers went to great lengths to make sure fans believed the sport was real. Watts, with his own football background, took this effort to greater lengths than most.”Because black athletes were excelling in all the other sports, Watts felt it would expose the business as being fake if no big wrestling stars were black. There had been black wrestling stars up to that point, but none had ever been the star in a promotion, and none excited Watts.”

In early chapters, Klein writes about the near 300-pound Ritter as a standout college football player, who tried out with the Green Bay Packers before transitioning from the gridiron to the squared circle in the mid-’70s. Using several different ring names, such as “Big” Daddy Ritter, while working for territories in Tennessee and Stu Hart’s famed Stampede Wrestling, Ritter was eventually christened the Junkyard Dog by Watts.

Klein also sheds light on the origins of the Junkyard Dog’s trademark dog collar and chain: “At first, JYD came to the ring with a wheelbarrow full of junk, a wrestling version of the television show Sanford and Son. That gimmick didn’t stick. However, another one did stick: a dog collar around JYD’s neck that was attached to a steel chain. In fact, the gimmick would be used for the JYD’s specialty grudge matches, called Dog Collar matches and would be with him for the rest of his wrestling career.

“Music played a big role in JYD’s success, too. Before music videos and before most wrestlers had theme songs, Queen’s Another One Bites the Dust would shake and groove to announce JYD’s entrance.”

Indeed, villains like Ted DiBiase, Butch Reed, and The Fabulous Freebirds would all bite the dust in heated rivalries with the Junkyard Dog. JYD would also amass numerous reigns as Mid South North American Champion and Mid South Tag Team Champion.In chapters packed with names like Ernie Ladd, Leroy McGuirk, Grizzly Smith, Buzz Sawyer, Terry Taylor, Steve “Dr. Death” Williams and Hacksaw Jim Duggan, Klein describes in depth how the Junkyard Dog became the most popular wrestler in Mid South, drawing thousands of black fans weekly to the Downtown Municipal Auditorium, nicknamed “The Dog’s Yard.”

Klein writes, “Wrestling served as a great melting pot in the South in much the same way sports did. Everyone could come together and cheer for the Junkyard Dog.”

The chapter Race, Rasslin’, and Nola is especially insightful, comparing ethnic heroes like Pedro Morales, Mil Mascaras and Bobo Brazil to ethnic villains like Ivan Koloff, The Iron Sheik and Kamala. “Pro wrestling critics often base their disapproval on stereotypes and xenophobia in the sport,” writes Klein. “On one point, at least, critics and supporters agree: wrestling does, in fact, exploit nationality and ethnic stereotypes to create drama. The only difference between the two groups is that wrestling supporters seem to enjoy the use of character.”

In many ways, the book is a historical ethnography of the Mid South territory, not merely a biography of the Junkyard Dog. It isn’t until late in the book — chapter 8 of 10 — that Klein takes us to the WWF of 1984, where JYD would skyrocket to international fame.Klein describes JYD’s meteoric rise and the mid-’80s landscape of the WWF — from The Wrestling Classic to Saturday Night’s Main Event to WrestleMania — and of Bill Watts’ numerous attempts to manufacture the next black superhero in the floundering Mid South, from “Hacksaw” Butch Reed to “Master Gee” George Wells to Eddie Crawford (The Snowman).

Klein takes the final chapters of the book to describe brief feuds like Junkyard Dog’s rivalry with Ric Flair over the World Championship, upon returning to the NWA (later WCW), before retiring in 1993.

JYD’s battles with drug addiction and the toll his life on the road took on his family are also chronicled. “JYD had been a notorious user, even in his Mid South days,” writes Klein. “Now, he was making three or four times as much money, with most of it still going up his nose.”

Although Klein’s research and storytelling are admirable for most of the book, there are some odd inclusions that seem at odds with the facts. In Chapter 9, for instance, Klein exaggerates the Junkyard Dog’s weight during his run in the WWF, stating “he ballooned even further, to the point where he was probably closer to 400 pounds.” Many fans would argue the Junkyard Dog was never more than 300 pounds before he left the WWF in 1988.

Sadly, the Junkyard Dog’s life was tragically cut short in 1998, while driving home from his daughter LaToya’s high school graduation in North Carolina. Ritter was involved in a single-car accident on a Mississippi highway that claimed his life at the age of 45.

In the epilogue The Forgotten Hero, Klein laments: “Still, dying in a car wreck is no better than an overdose or suicide in wrestling or any other walk of life. Whatever the details, Sylvester Ritter was gone, and after wrestling and the world at large had moved on, many of his friends had not. Many indicated their hopes for him to kick his addictions, or for a never-realized comeback. Others saluted his never-ending generosity, and how, even when he was down and out, he would always help someone in need.”The book concludes with Klein questioning why the Junkyard Dog has not been inducted into the Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame in Amsterdam, New York, which in recent years has inducted Ted DiBiase (2008) and Bobo Brazil (2009). “So far, the only wrestling hall to induct the Junkyard Dog is the one with the least objective standards, the WWE Hall of Fame,” writes Klein. “This hall of fame is widely regarded as less of a reflection of the history of professional wrestling than as a reflection of the history of professional wrestling when viewed through the filter of the bias of the WWWF, the WWF, and WWE.”

Earlier in May, Junkyard Dog entered the Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame as a part of the Class of 2012. Written before the honor, Klein was optimistic that JYD would someday find his rightful place in the Hall of Fame in Amsterdam.

Writes Klein: “(JYD) was the first African-American wrestler to be made the top star of an entire wrestling territory, a feat more remarkable given the history of racial unrest in the Deep South, as well as the backlash during the civil rights era.”

The King of New Orleans is remarkable in its own right — a compelling and long-overdue tale of a man who deserves to be remembered as a pioneer and inspiration to many.