Rick O’Toole hadn’t turned 18 when he beat wrestling great Ernie Ladd. It wasn’t the cleanest of wins, to be sure — O’Toole won by disqualification in a TV match on June 13, 1971, when a TV commentator went off script.

But as O’Toole, or Rick Brogdon in real life, acknowledged, you take what you can get in wrestling. “I’d do it all again in a heartbeat knowing what I have done to my body. No problem,” he said in an interview with SLAM! Wrestling last winter. “Even got some pretty nifty prizes like my house, my wife, and my degrees. Not a bad trade off, eh?”

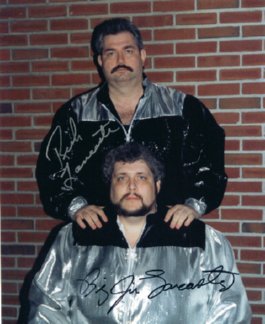

Rick O’Toole as Rick Lancaster stands over long-time tag team partner Jim Lancaster. Photo courtesy Jim Lancaster

O’Toole was an undercard worker, mostly in the Midwest, from the time he debuted as a 16-year-old for The Sheik’s Detroit-based promotion. So when, in ill health for years, he died February 6 at 58 at his home in Michigan, wrestling didn’t lose one of its biggest stars. But, according to his friends and coworkers, it did lose one of its truly good people.

“Rick was well-liked by all the guys in the territory. He understood that there was a job to do and he did it,” said Big Jim Lancaster, who followed O’Toole into the Detroit territory and teamed with him as worked brother Rick Lancaster in Midwest Championship Wrestling in the 1980s. “He was probably more grounded than anybody I came across at the gym at that time. He always had a job and was taking college classes. To him, it was, ‘Hey, we’re wrestling. It’s here for a while. Let’s have fun with it, don’t get hurt, and save your clippings because there won’t be very many of them.’ ”

O’Toole was born December 12, 1953, the only boy in a family of seven children born to a U.S. Army dad and an Irish immigrant mom, and was raised in the Mt. Healthy area of Ohio near Cincinnati. A devout wrestling fan, he signed up in June 1970 to train at Lou Klein’s Detroit-area wrestling school on weekends and summer vacations, much against the wishes of his mother, a nurse.

During his high school years, his wife Karen recalled, O’Toole would hop a bus to make a match at Cobo Hall in Detroit — he debuted there in September 1970 — and return to Cincinnati just in time for class. He moved to Allen Park, Michigan, the site of Klein’s proving ground, on June 9, 1972, the night he graduated from high school. “I was young, had a lot of energy and I wanted to set the world on fire,” he remembered.

As a teenager, O’Toole was mostly or preliminary or TV match fodder in Detroit, Pittsburgh, Cleveland and Toronto for the likes of Fred Blassie, George Steele, Dr. Bill Miller, Pat O’Connor, and Chief Jay Strongbow. “We took our bookings as much as we could. The payoffs were small when you worked underneath most of the times. The call came from Williamston [Ed “The Sheik” Farhat’s Michigan home] to Klein’s gym. We went,” he said.

A moment that would last a lifetime came during a TV taping in Walled Lake, Michigan, where O’Toole was supposed to be quick and easy fodder for Ladd. In fact, Ladd quickly thrashed O’Toole until The Mighty Igor (Dick Garza) got to the ring and started in on the supervillain. Lancaster, still a fan at the time, watched the whole thing unfold on TV. Igor chased Ladd off the set, even as O’Toole struggling to stand up.

“It was a mistake finish,” Lancaster explained. “Lord Layton was doing the announcing and he was the one who announced it was a disqualification and Rick O’Toole was the winner. They weren’t supposed to talk about a winner or a loser, but just talk about the atrocities Ernie Ladd was putting on this young man. Nobody was more surprised than Rick except maybe Sheik.”

O’Toole, who filled out generously to about 5-11 and 300-plus pounds after he left his teen years, started wrestling intending to be a fan favorite, with women flocking at his feet. After he was in the business a while, he said he believed it was more fun, productive and financially rewarding to wrestle as a bad guy.

“I’ve done the babyface deal in air-conditioned gyms and I worked under a hood in a small armory in Plymouth, Indiana, with no A/C, the temperature at 95 degrees at 8:00 p.m. My choice? Where did I put that hood and brass knuckles? Heel it, baby! Heel it!” he said. “Anyone can get the nun in the third row upset and angry if you stand in the ring and yell abusive cuss words and make obscene gestures. But, if you can use holds and simply stares to get your heat, then you’re working the business.”

To make ends meet, he worked at Plymouth Centennial Educational Park as part of an expanded security and safety team, with two high schools on the same property. “Rick loved working with the kids,” said Karen, whom he married in 1976. “He would always tell them, ‘There’s a time and place for everything; get your priorities straight.’ The more time he spent with the day job. the harder it got to make wrestling shots every weekend.”

O’Toole also wrestled a little in St. Louis, Tennessee, and Florida, as well as in independent promotions run by Fred Curry and Ricky Cortez, which popped up when The Sheik’s office faltered in the mid to late 1970s. He cut back on his wrestling around that time, but still was a fixture in Lancaster’s MCW promotion from 1982 until the pretend wrestling brothers retired August 9, 1992, following a tag match in Jackson Center, Ohio.

“He was kind of a stabilizing voice in the dressing room,” Lancaster said. “He wasn’t interested in working any big matches or main events. He liked working with some new guys to walk them through a match, calm them down if they got a little excited about being out there. He really enjoyed that mentoring type of thing.”

Mickey Doyle, Rick O’Toole, Al Snow and Jim Lancaster at the Midwest Championship Wrestling Hall of Fame. Photo by Dave Burzynski

Like many undercard wrestlers, O’Toole was an astute observer of wrestling — a fan at heart — with insights into the business that bigger names or bigger egos might be unable or unwilling to offer. Bearcat Wright was one of his opponents on TV and in the long-gone Cleveland Arena, and O’Toole remembered exactly what he encountered. “I was an acquaintance, but he did portion off enough of his own territory to stay by himself. Only interaction was to get told what the finish was. Bearcat did not give any job guy much. He had good size huge hands. Bumps were not his favorite, either. Women loved Bearcat because he was … well, let’s say he was gifted more than in just getting booked in the ring.”

A big University of Michigan fan, Brogdon also cohosted a local cable TV show called the Rick and Wick Show that spotlighted local high school activities. “This was not Rick’s original idea but he had a great time with it,” Karen said. “They would maybe have a teacher on whose hobby was very interesting or maybe something new happening at the school. Sometimes they might have a cooking segment. At one point, they even started to take the show on the road and highlighted some cities and businesses in Michigan.”

O’Toole suffered a heart attack around Thanksgiving 2003 that went undetected for several weeks. Health problems plagued him for the rest of his life. He had a triple bypass and a pacemaker operation, and he struggled to control diabetes. After his heart trouble, O’Toole found Igor was making the save once again, just like in the match with Ladd, when they ran into each other rehabbing at Henry Ford’s Greenfield Village in Dearborn, Michigan.

“I said, ‘Iggy, what are you doing here?’ as I noticed he had lost at least 50 pounds. He told me he had a bypass operation and was doing cardio. I said, ‘Me, too,’ as I lifted my shirt straight up and he did the same thing. We literally stood there with our arms and shirts comparing scars to see who had the better ‘zipper’ job,” O’Toole joked.

In recent years, between trips to a battery of doctors, O’Toole and his wife created and assembled programs for the homeless, hungry and elderly as part of a nondenominational group called Faith As One Volunteers. Among the activities: a lunch bag program for the homeless that produced 650 sandwiches last November. “We are just a bunch of people who get together to help give a hand up to someone, or some organization. And Rick was our leader. He organized, shopped, delivered, and wrote the newsletter until he couldn’t do it anymore. I was always there to help, but he was in charge,” his wife said. “He believed everybody should do some type of service. To him, that meant you helped someone out and you walked away with nothing but a good feeling.”