When Dan Kroffat returned to Stampede Wrestling in late 1984, he warned Stu Hart that he wouldn’t be able to work like he used to. Though the boss knew why, Kroffat never told the boys in the dressing room about his new handicap. In the locker room, explaining how you’d survived a gunshot to the left arm during a seven-hour hostage-taking incident in a British Columbia prison would simply have been taken as bragging.

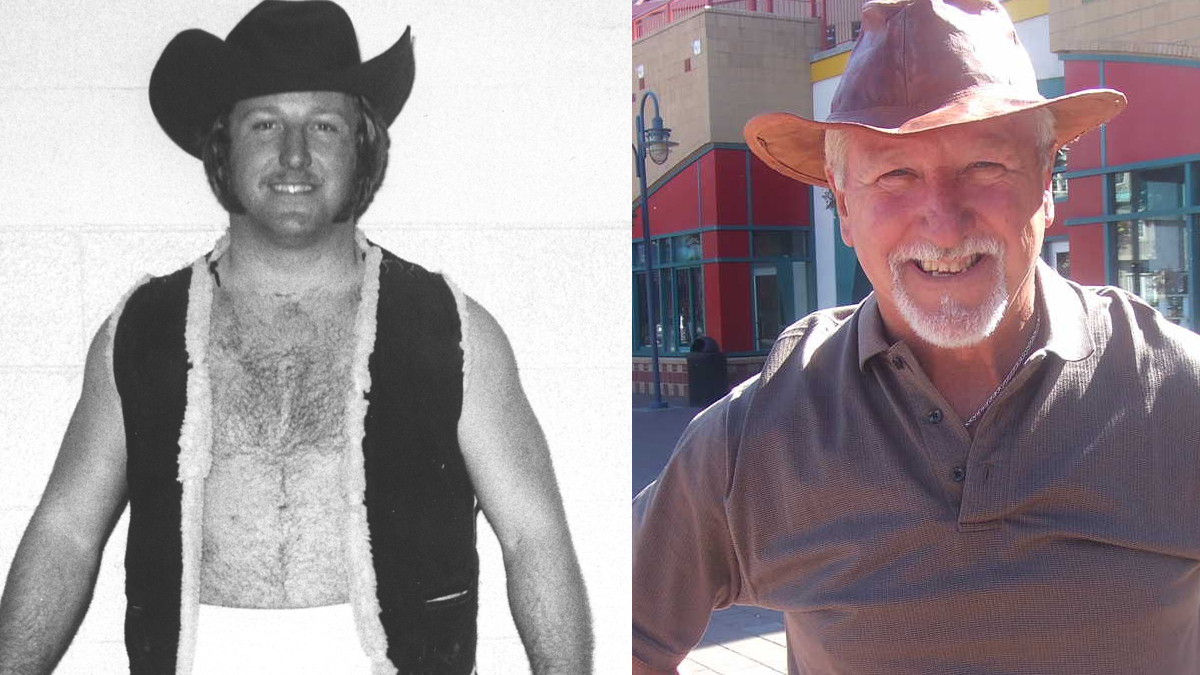

Dan Kroffat, held hostage, in a video still from a National Film Board training film shot after the October 1984 incident.

It is a part of his life that the Calgary-based Kroffat had set aside, perhaps repressed, and not really talked about until it was brought back into the forefront of his life. The British Columbia government, going through its files, revisited the hostage taking at the Vancouver Island regional correctional centre in Saanich in October 1984. It determined that Kroffat, for his conduct as a hostage in the tensest of situations, deserved a medal for bravery, as did his colleagues.

So in January, Kroffat headed out to Victoria for a ceremony, and decided to share his memories of the incident — the good and the bad — with SLAM! Wrestling readers.

Kroffat had been a lifeguard in Vancouver; Barbadian wrestling star Earl Maynard saw him there and thought Kroffat would be a great wrestler. Maynard hooked up Kroffat with Stu Hart in August 1969, when he took off for Calgary with his wife to start a new life. After a thoroughly entertaining career in pro wrestling, which saw him headline in Calgary and Los Angeles primarily, Kroffat was ready to try something else. His family, which now included two daughters, settled on Vancouver Island, and he took part-time work as a prison guard.

Given his background in combat and his smarts, Kroffat was quickly conscripted to teach self-defence to the prison guards. During his couple of years in the penal system, Kroffat rose to become a “search master,” trained for search and shakedown, looking for contraband in prisons.

Following a tip from police that a gun had been smuggled into the prison, the Vancouver Island regional correctional centre was in lockdown on that fateful day. Prisoners were confined to their cells, even for meals, as guards conducted a “brick-by-brick and flagstone-by-flagstone” search for weapons.

Around 9:30 p.m. on Thursday, October 4th, things were returning to normal at the prison, when one of the prisoners, escorted back to his cell after a shower, bolted down the hall, pulled a .32-calibre handgun out from under some towels and took four guards hostage.

The prisoner was Roderick Myles Camphaug, a 34-year-old man who was awaiting trial on a first-degree murder charge for the killing of Diana VanDooren, 57, of Duncan, BC, on May 27, 1984. Gordon Michael Pawliw and Roderick Edwin Schnob were also charged in the first-degree murder. All three were later convicted, and sentenced to 25 years in prison without parole. Court testimony revealed that the men had been hired to commit a contract killing on her husband, Dennis Vandooren, but had bungled the hit.

One guard quickly escaped, while another, Ted Anchor, was trapped in the locked-down east wing, though not under Camphaug’s immediate control. The remaining hostages — Kroffat and Jim Shalkowski — were ordered down the stairs into a day room. Camphaug demanded the release of his fellow accused, which officials denied, and he threatened to shoot, firing off one round into the wall over the staircase as a demonstration.

Kroffat stood his ground and said, “Do what you have to do.”

“To this day, I have no idea why I said that,” recalled Kroffat.

Camphaug, respecting the stance, said, “You’ve got balls, I’ll keep you around.”

In another still from the training film, the hostages face their captor.

After initially putting the guards into a cell, Camphaug reconsidered, and told the hostages to remove all their clothing and take a seat. Kroffat was ordered to sit on one side, Shalkowski the other.

Again, Camphaug demanded his friends be released. Rebuffed, he shot Kroffat.

The bullet went right through Kroffat’s left arm, “blew the radius bone to bits, and exited out the back, close to my shoulder.”

Kroffat gave the short version of the next seven hours, spent on the floor, naked and bleeding.

“After I hit the ground, I was comfortable for a while, and of course, I kind of played dead — ‘Let’s just see what happens.’ The blood started to form around my body. I could feel it running out pretty profusely. I got thinking more and more, ‘I’m going to bleed to death here.’ So I took my thumb and put it in the bullet hole in my arm and it stopped the bleeding. Then as I lay there longer and longer, I thought, ‘I’m not getting out of here.’ So I made three hearts, and I put my daughters’ initials in two of them, and my wife’s in the other one to send them the message that they were my last thoughts in this situation.”

Unbeknownst to the hostages, a SWAT team had arrived, and deposited microphones in the room, recording at least six hours’ worth of dialogue — handy for a training film that the National Film Board later put together to help guards understand how to react in a similar situation. (Ironically, Kroffat learned he had a different kind of fame than wrestling through the film, as many guards at the January 2012 ceremony told him they’d seen the movie. “I didn’t realize that it had more exposure than I’d even anticipated it to have.”)

According to Kroffat, as the hours went by, Camphaug started to break down, but never let himself get in the sights of the six SWAT rifles pointed at him.

On the phone in the day room around 11 p.m., about 90 minutes into the incident, Camphaug ordered Shalkowski to call the local radio station CKDA. “I am not going down for 25 years on a bum rap, but I guess I’m going to have to go down for shooting a pig and that’s unfortunate,” Camphaug said. “I shot one of them and if there’s any action at all I’ll blow him away.”

CKDA radio news director Clive Kitchener was one of the men brought in to work with police as a negotiator. The other was Abbotsford lawyer Jack Harris, who had worked with Camphaug on his divorce. Police chartered a plane to bring Harris to the Island in the middle of the night.

“I tried to develop rapport. One thing that was important to him was that I trusted him, and that he trusted me,” Harris told the Vancouver Sun after the incident. Harris convinced Camphaug to prove he was a man of his word, and allow Ted Anchor, the guard on the upper tier, to leave.

Harris was allowed to get close enough on the phone to see Kroffat, in a pool of blood on the floor, but obviously still alive. He started negotiations for Kroffat’s medical attention.

Having agreed to Kroffat’s release, Camphaug reneged when he was told that the attendants bringing in the stretcher might look bigger than normal. Sensing it was a set-up for the SWAT team — Kroffat later learned that medical personnel did not want to enter the situation — Camphaug said no.

“Of course, my heart went from, ‘I’m getting out of here!’ to, ‘Oh my God, I ain’t going anywhere.’ You talk about an emotional high and an emotional low all in a short period of time,” recalled Kroffat. “After a while, I started thinking about it — ‘Wait a minute, he agreed to let me out. It’s just the conditions in which he won’t let me out is not letting them come in.’ So I piped up finally after all these hours, I said to Camphaug, I said, ‘Listen, if I can get myself out of here, are you still willing to live up to the agreement, what they discussed?’ He said, ‘How are you going to do that?’ I said, ‘I’ll pull myself off the ground and I’ll crawl to the gate’ — gate being in the day room, these big steel gates where the doors are — I said, ‘If somebody slides a key to me, I’ll open it. I’ll let myself out.’ He waited a moment or two and said, ‘Yeah, you can do that.'”

A set of keys were tossed to Kroffat, who needed them to open the gate at the top of the stairs from the inside.

“Somebody, he must have been a bowler, he slid the keys and they hit my hand perfectly. So I was able to pull myself up, put the key in this archaic old door. I swung it open, and I swung open with it on the bar. Here I am, covered in blood, naked. I swing out on the door, and all of a sudden, Camphaug comes over to the door, points the gun at me, and says, ‘You know what? I’m not sure I’m going to let you go.’ … I looked at him and said, ‘Whatever.’ He looked at me and said, ‘Get out of here.’ I was out the door and I was gone. I made it. That was the end of it.” (News reports noted that Kroffat walked to the ambulance under his own power.)

By 4 a.m., Camphaug had had enough. Harris arranged for safe passage for Camphaug out of the day room. Camphaug walked behind Shalkowski with the gun and handed the gun to Shalkowski. Harris then put himself between Shalkowski and Camphaug as a shield for the walk out. Authorities handcuffed Camphaug and led him back to his cell.

The incident was a big story on the Island. “Daffodils blooming on the Island is usually a big story so a hostage taking and shooting is like, God, the Twin Towers coming down in New York as far as Victoria was concerned,” said Kroffat. Follow-up stories by the local media included visits to Kroffat in the hospital and the psychological effect of the hostage-taking on the warden.

Dan Kroffat, second from right, at a January 2012 ceremony in Victoria, honouring the hostages.

Off on leave for a couple of months, Kroffat started back to work, and said he didn’t suffer from any post-stress issues. His then-wife, however, was a different story. With two young girls at home, she begged him to find another line of work.

“They kept me on, technically, for about six months in an employment role,” said Kroffat, who ended up being pensioned off because of the injury.

The family headed back to Calgary

“Before you know it, I was training, working out again. Before you know it, I was working with Honky Tonk [The Honky Tonk Man] and working the shows, the ladder match, and away I went,” Kroffat said.

At 40 years of age, he was planning for an exit from wrestling again.

“I knew that my wrestling didn’t have a lot of life left in it. I don’t know if it’s a blessing or a hindrance, but I look at everything long-term, and I realized that the window was closing,” he said. Settling on the automobile business, Kroffat found a location for Daniel’s Auto Wholesale Centre.

Dan Kroffat takes to the podium at a January 2012 ceremony in Victoria, honouring the hostages.

He found that his fame from wrestling helped.

“When I opened, I had an immediate response which would give me a pretty successful opening. Of course, 20 years later, it proved to be that,” Kroffat said. “I was extremely lucky and successful at the car business in Calgary. It really worked out well.”

Now retired from the car business, Kroffat lends his expertise to a variety of charities and causes.

As for Camphaug, he would later end up in the news in 1988 for having an affair with a prison employee at Kent Institution, taking his objection to being moved to solitary confinement and out of the prison to the Federal Court of Canada, which ruled that he had been treated fairly. In 1991, he went to court again — and again unsuccessfully — protesting being sent to solitary for his role in a prison beating.

RELATED LINKS

Greg Oliver, the Producer of SLAM! Wrestling, appreciates the trust of Dan Kroffat in sharing this very unique story. Greg can be emailed at goliver845@gmail.com.