Aboriginal wrestlers over the years haven’t always agreed on how their heritage should be portrayed and exploited for professional wrestling’s gain. Some were comfortable with the headdress and the war dances, and others eschewed the cultural shortcut completely.

Gerry Brisco, from the Chocktaw and Chikasaw tribes of Oklahoma, was one of those who elected not to play a stereotype, the same path as his older brother, the late NWA World champion Jack Brisco.

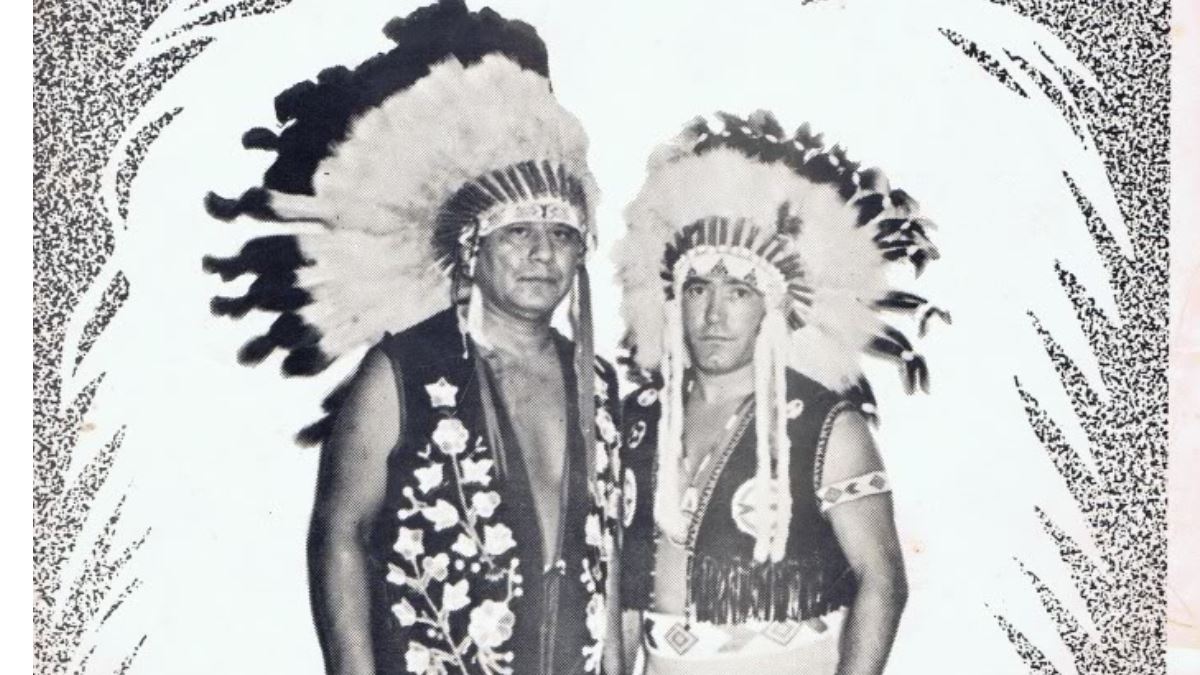

Billy Two Rivers in 1956.

“I just kind of had a different belief. Even during the beginning of my career, some of the promoters, some of the bookers said, ‘You ought to go as a Native American’ — Indian at that time. I never would do it because I just didn’t feel like that was the right thing for me to do,” Brisco told SLAM! Wrestling. “I never held it against them. I always begrudged the guys that weren’t Native Americans and went out and dressed and pretended to be Native Americans — some of the Latinos and Italians, and guys like that, I’m not naming names.”

Native American and Canadian wrestlers have been in pro wrestling almost from the start of the pro game, or least a reasonable facsimile there of.

The greatest of the early “Indians” would be Chief Chewacki, a wildman born George Mitchell from Oklahoma. Chewacki was primarily a Depression-era wrestler who would do anything for a buck.

Suni War Cloud (Joseph Chorre) was among the first of the big TV stars, wrestling out of California; in fact he wrestled throughout a film career.

Jerry Christy, the nephew of Vic and Ted Christy, got to see Suni War Cloud at his peak. “He was an Indian, he did the war dance and all that stuff,” Christy said, adding that War Cloud’s war dance was “the best out of all of them.”

Chief Kit Fox of Oklahoma’s Delaware Tribe and Chief Big Heart were two of the bigger names of the 1950s and 1960s.

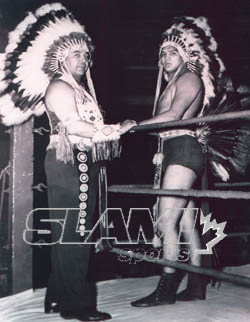

War Eagle and Don Eagle. Photo courtesy James C. Melby.

From Canada came Chief Thunderbird, of the Tsartlip tribe, and War Eagle, a Mohawk from the Kahnawake reserve outside Montreal, whose son, Don Eagle, would be the first Aboriginal with a legitimate claim to a version of the World title, in 1950.

Don Eagle later trained Billy Two Rivers to be a pro wrestler.

Two Rivers had decent success in the Carolinas and across Canada, but in Great Britain, he became an icon, with his Mohawk haircut and war dance.

Typical of the time is a 1957 story from the Sheboygan, Wisc., newspaper previewing Two Rivers’ appearance:

“Billy Two Rivers is a Mohawk Indian who is but 22 years old and has been wrestling four years as a pro. He is very colorful as he enters the ring attired in his Indian head-dress and costume. Billy hails from a reservation in Caughnawaga, Quebec, Canada, and is one of the speediest wrestlers in the mat sport,” it reads. “Fans have compared Billy with such other outstanding Indian wrestlers as Chief Little Wolf, Chief Big Heart and Suni War Cloud. He has a specialized hold he calls the Indian Tomahawk.”

“I wasn’t a hero, I was an ambassador,” explained Two Rivers. “Representing the Kahnawake specifically, the Mohawk people, and then the Native people of North America.” He stressed that he never had a discussion with promoters about what he was trying to do, and that he would have said no to anything dastardly.

“People had a different image of us, we were still stereotyped from books and whatnot as being stoic people and conservationists, and all the other things that go with it,” he said, continuing, “except here in Quebec and Canada, where we were sort of criminalized for being wild and uncivilized and everything else that goes along with it to justify their theft of our property.”

Jerry Brisco, alongside his brother Jack, mockingly wears Jay Youngblood’s headdress in a famous angle from the Mid-Atlantic territory in the early ’80s. Photo by Bill Janosik.

Both Brisco and Two Rivers admitted there was racism on the road.

“There were a lot of rednecks everywhere, because they knew they were occupying our land,” said Two Rivers.

“I grew up in Oklahoma, of course, during the ’50s and the ’60s, when there was a lot of racism towards Native Americans,” said Brisco.

On a few occasions, Brisco said he and Danny Little Bear talked about the role they were playing as Native Americans. Little Bear had chosen to play up the gimmick.

“He said, ‘It’s who I am, and it’s my way of getting out the word that we’re good athletes, and we’re capable of doing something,'” recalled Brisco. “There was a negative perception, even at that time, towards the Native Americans, in the Midwest, the Southwest, and all that. I look back on it, and the ones that were true Native Americans, I really had no problem with it. I just looked at it as the old Hollywood perception of, ‘This is what a Native American is.’ I know a lot of ’em did what the promoters told them to do, and that’s what they did. Jack and I were kind of different. We were athletes and that was our way of showing what Native Americans were.”

Gerry Paquette, of Teton-Sioux heritage, had a short career in the early ’70s. His stint in wrestling is the only time he was asked to capitalize on his culture. “The people that were interested in Indians, they wanted to see it. I never pushed the thing out, I was just the way I was,” said Paquette, who worked as Gerry Goodvoice and Jay Clintstock. “I did a little bit more in the ring than I did anywhere else, but then it was all feathers and bright colours, eh.”

Being a nice person went a long way towards avoiding racism, said Two Rivers. “Even in the Deep South, where there’s a lot of prejudices and racism, I was respected and welcomed in different societies — the Old Boys Gang, the tailgate parties, the colored sections up in the bleachers,” he said. “But they came to the wrestling matches and were very cordial, and I got along good with the local people. There were a lot of them that were very, very racist towards non-whites.”

Though Native Americans were often the babyfaces, some, like Bull Ramos, took to the evil role like he was born to be bad.

Perhaps the greatest Native American athlete was Jim Thorpe, the Olympian/baseball/football player from the 1930s, who was named the greatest male athlete of the half-century in an Associated Press poll. He did briefly try pro wrestling too, wrestling in the late 1940s a little, and even had a brief stint as a manager.

Manager Crazy Horse, left, with his charge, The Chief (Chad Blind).

But as far as great athletes and longevity in pro wrestling go, none could touch Wahoo McDaniel. The Choctaw-Chickasaw Indian from Oklahoma was a star football player at the University of Oklahoma, before going pro and then into wrestling.

“Who was Wahoo McDaniel?” Florida sportswriter Dave Hyde asked after his death at age 63 in 2002. “Who wasn’t he? An American Indian, an expansion Dolphin, a legendary wrestler, an old-time carouser, a full-time personality, an Oiler, a Bronco, a Jet, a guard, a linebacker, a kicker — he was the kind of figure we lost long ago on the sports pages: an original.”

“Wahoo and I were dear friends,” said Brisco. “There’s a short list of great, great, great Native American athletes, and Wahoo McDaniel is, in my mind, is right up there with the Jim Thorpes and the Jack Briscos, guys like that that were great Native Americans.”

“I look at him a lot different. He was an Oklahoma football player, a pro football player. He was just an outstanding athlete,” continued Brisco. “I think when he went out into the ring, he left the feathers on the ring post, and proved that he was an athlete. He didn’t do all the stuff. He had the intensity and the fire of a Native American. … He was the real deal. There was no other way to describe Wahoo.”

More recently, names such as Jay, Mark and Chris Youngblood, Charlie Norris, Steve Gatorwolf, and Tatanka have solidified the legacy of Aboriginals in professional wrestling. On the distaff side, Sandy Partlow, Princess Tona Tomah, Princess Little Cloud (Dixie Jordan) and Alere Little Feather.

Princess Victoria.

Vicki Otis, whose father was of Saanich descent, never questioned her decision to work as Princess Victoria.

“I wasn’t really using it, I am Indian. I’ve always gravitated towards the Indian side,” she said. “I didn’t have to go out and buy anything for my first outfit. My first ring outfit, the white skirt with the embroidery on it and the white vest? I already owned it. The moccasin boots that I wore on my first match? They were boots that I already owned that I just had them put a thicker sole on them.”

Now a respected speaker and a published author on the subject of aboriginal youth, Dixie Jordan does have some regrets about the Princess Little Cloud name given to her by the Fabulous Moolah, and which she used for the majority of her six-year career.

“[At the time] I didn’t care, I was a kid. It’s a different landscape today,” said Jordan, of Apache/Cherokee descent, taking a shot at the magazines and programs of the day. “They wrote ludicrous stuff about getting special travel dispensation to wear a headdress and all this silly stuff. … It would be nice if publicity could be honorable and somewhat honest.”

— with files from Steven Johnson

TOP PHOTO: Billy Two Rivers and a younger War Eagle (not Don Eagle’s father).

WHAT YOU THINK

Who was the greatest male Native professional wrestler of all time?

Wahoo McDaniel – 54%

Jack Brisco – 18%

Tatanka – 15%

Don Eagle – 2%

Billy Two Rivers – 2%

Gerry Brisco – 1%

Danny Little Bear – 1%

Other – 6%