If WrestleMania was Randy Savage’s greatest theater, then the Paducah, Ky., National Guard armory was his proving ground.

Izzy Slapawitz remembers it well.

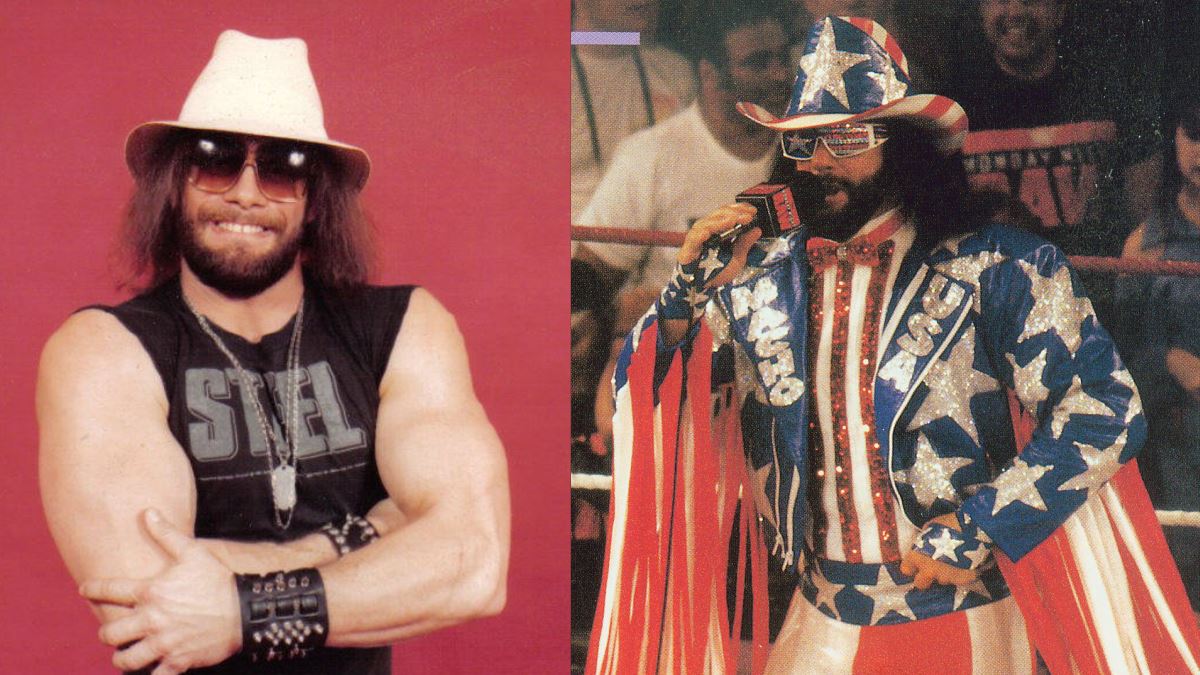

A very young Randy Savage works in Detroit. Photo by Mike Lano, WReaLano@aol.com

One night some 30 years ago, Savage was riddled with the flu, horribly sick and running a high fever a few hours before he was supposed to wrestle in the armory. The wild-haired Slapawitz, who managed, wrestled and feuded with Savage, was among co-workers who suggested he take a catnap, promising to rouse him for his match.

Savage put down his head and was out like a light. The crew sent a substitute in his place and allowed “Macho Man” his much-needed rest until the arena emptied of fans. Then, most of the wrestlers went into the ring area clad in their underwear, or less.

“We woke Randy and said, ‘OK, Randy, it’s time for your match,'” Slapawitz recalled with a laugh. “He got dressed in full regalia, put his robe on, they started playing his music and he walked out and there are all these half-naked guys cheering, ‘Yay, yay!’ He cracked up laughing.”

That was the band-of-brothers mentality in International Championship Wrestling, a renegade promotion run by Savage’s tight-fisted father Angelo Poffo, where Savage restlessly rode the back roads to places like Combs, Ky., and Lexington, Tenn., honing the character that would become a cultural icon.

“He was a guy that you knew was destined for greatness. He just had it. You could see that here was a guy who was going someplace. He knew how to gauge the fans,” Slapawitz said.

Slapawitz — in real life, Jeff Smith of New York City — was in cardiac therapy for a heart-related issue when he got the news Friday that Savage, 58, had died following a single-car accident in Seminole, Fla.

It’s not too trite to say that he was heartbroken.

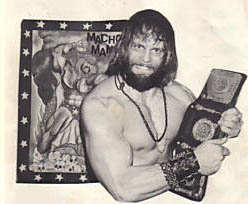

ICW champion Randy Savage. Photo courtesy ICW Poffo Universe |

“I went to therapy and as I walked in, one of the guys there shouted to me, ‘Hey Jeff, did you hear Macho Man died? Did you know him from your wrestling days?’ And it hit me like a ton of bricks,” said Slapawitz.

By the time Slapawitz got to ICW in 1979, the “Macho Man” character was already pretty well-defined. Savage puttered with wrestling before going full-time in 1975, not long after his pro baseball career ended, under his real name of Randy Poffo. He debuted the Savage alias in 1977 in Georgia with booker Ole Anderson.

In January 1978, when Savage started in Nick Gulas’ eastern Tennessee territory, the pieces started coming together — the avant-garde robes, the freaky hats and bandannas, and the guttural voice that sounded like a peach pit was lodged deep in his throat.

Slapawitz first served as Savage’s manager in some towns co-run by ICW and the All-Star Wrestling promotion in Knoxville, Tenn. “His gimmick was pretty much in place by the time I met him. I think that’s when he did his best work. I really do. I think most of the boys did. It was a pity that the exposure was so limited. I think most of the boys at that point, and certainly Savage, were doing their best work,” he said.

At the time, Savage was a wicked heel, with seething, intense eyes that suggested he might go haywire at any instant. In one gasp-filled angle, Savage rained down a brutal flurry of top-rope elbows on midget Wee Willie, who was in a running feud with him and Slapawitz. The incident was a set-up to supposedly injure Willie and help him secure insurance for a surgical procedure, but for fans, it made Savage’s volcanic character more credible.

“That’s what did it. When people looked at him, they believed that’s who he was. And the truth of the matter is, his gimmick is was who he was. His ring persona was just a cartoon of his real persona; it was just emphasized more,” Slapawitz said.

Slapawitz identified creativity as one of young Savage’s great strengths. “Randy was creative and he listened to other ideas. We had meetings and tossed around stuff that we wanted to do, and Randy would listen. Randy had some good ideas on a lot of stuff,” he said.

But while he was agreeable most of the time, Savage also was tightly wound, and became even more tightly wound as time went on, a trait many of his contemporaries ascribed to steroid abuse.

Regardless of the cause, he could be disturbingly edgy and suspicious at times. Once, Slapawitz recalled, Savage related a vivid dream sequence in which his fellow wrestlers were talking about him behind his back.

“I said, ‘Randy, nobody’s talking about you. We’re all friends here,'” Slapawitz said. “We were a very tight group. In fact of all the territories I worked in, that was the tightest among the boys, except for maybe one or two guys. So I told him, ‘No, Randy, nobody’s talking about you.’ But he really wouldn’t believe me.”

|

The Devil’s Duo, Doug Vines and Jeff Sword, with manager Izzy Slapawitz. Photo courtesy ICW Poffo Universe |

In a final angle, Savage broke with Slapawitz, feuded with his prized tag team of Doug Vines and Jeff Sword, and place a $2,000 bounty on Slapawitz’s over-coiffed head. Under a mask, Pez Whatley did the honors of ridding ICW of Slapawitz in 1981.

In reality, the parting was less than amicable. ICW suffered a talent exodus at about the same time, and Angelo Poffo, known as the Miser to friends and foes for his penny-pinching ways, identified Slapawitz as the cause.

“Angelo, and Randy I guess also, blamed me for everybody leaving which really wasn’t the case,” Slapawitz said. The fault rested more with low payoffs and numbing circuits throughout the territory, which included shows from parts of Virginia 500 miles west to Cape Girardeau, Mo.

“For most of the trips, most of the guys got in the back of the ring truck. For hours, they rode like that,” Slapawitz said. “Miser used to give us all sorts of hell for driving, and called us prima donnas. The trips became so unbearable and the payoffs were so low that people started saying, ‘Hey, what are we doing here?'”

Slapawitz last saw Savage when they appeared together at a WWE show in 1991 in Chattanooga, Tenn., so to him, the Slim Jim-chomping star who acted in the first Spider-Man movie is an image on a screen.

But Slapawitz still has a special fondness for the friend with whom he traveled, fought and laughed a generation ago.

“We were like kids playing out with our friends. We would just go out there and do stuff, and we used to drive the Miser crazy because he never knew what any of us would do, including Randy. It was really pretty cool,” Slapawitz said.

“Over the years, the good memories really overshadow the bad ones. It was just a shock for that to happen. He was really too young.”

RELATED LINKS