Leonard Maltin is one of the best-known movie critics and historians in the world. With the Oscars only a few days away, we ask, who are his favorite wrestlers in Hollywood? Which wrestler’s statue does he proudly displays on his desk? What does he think of WWE Films? Read on!

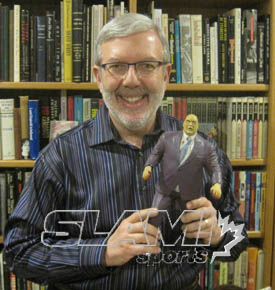

Leonard Maltin poses with his Tor Johnson figure. Photo by Jessie Maltin.

Maltin discovered professional wrestling through cinema. “I didn’t watch wrestling when I was growing up, and I know very little about it,” Maltin confesses at the outset. But this has in no way diminished his appreciation of the contributions of professional wrestlers to world cinema. In fact, Maltin’s assessment of wrestlers in Hollywood is invaluable to wrestling fans, since his is the eye of an unbiased film historian who can assess the acting prowess of wrestlers, minus the bias of any wrestling politics. As a critic who has appeared on Entertainment Tonight since 1982, and as the editor of the annual paperback reference, Leonard Maltin’s Movie Guide, Maltin commands some respect.

In an earlier interview, Maltin talked about wrestlers in the Silent Film Era. But who are his favorite pro wrestlers from the sound film era? His choices might surprise younger SLAM! Wrestling readers, but not veterans of the business. “I fondly remember Mike Mazurki, who continued wrestling even as he built a solid acting career, sparked by his inspired casting as ‘Moose’ Malloy in the Raymond Chandler mystery Murder, My Sweet (1944),” Maltin says of the founder of the Cauliflower Alley Club. “He became a talented character actor in a slew of movies — including classics like Some Like It Hot (1959) — although he was usually typecast.”

Mike Mazurki

The Austrian-born wrestler was happily typecast as a wrestler in the greatest film based in the world of pro wrestling prior to Darren Aronofsky’s The Wrestler, Jules Dassin’s classic film noir, Night and the City (1950). Playing The Strangler, Mazurki was part of a wrestling dream cast that also included Stanislaus Zybyszko.

ROD STEWART MAKES MAZURKI FOREVER YOUNG

After being largely forgotten in the 1970s, Mazurki enjoyed a renaissance in his career, thanks to a new art form of the 1980s: music videos. As the old cliché goes, back in the ’80s, MTV actually played music videos, unlike today when it specializes in reality TV, like TNA’s Cookie’s favorite show, The Jersey Shore. Mazurki appeared in one of the best directed music videos of the time.

“I had the great pleasure of interviewing him in the 1980s for Entertainment Tonight after he’d gotten a lot of exposure in a popular Rod Stewart music video, Infatuation,” Maltin reveals. Directed by the Emmy-nominated Jonathan Kaplan, the music video for Infatuation is inspired by classic cinema and, even today, stands the test of time as one of the best examples of the genre (Kaplan would later go on to direct many episodes of E.R. and Without A Trace). Maltin says that Mazurki was one one of the most important factors in making the video a success, by “playing the same kind of gangster type he’d perfected in so many vintage movies.”

Maltin is not alone in his veneration for Mazurki. It is his name that adorns Cauliflower Alley’s top honour, The Iron Mike Award, which is arguably one of the most prestigious awards that a wrestler can receive.

THE SUPER SWEDISH ANGEL

Perhaps the nearest and dearest professional wrestler in Hollywood for Leonard Maltin is Tor Johnson, who wrestled from the 1930s to the 1950s. A 1935 Galveston Daily News report purports that Johnson was “the son of a Stockholm grocer, and he thought he was doing well for himself when, on arriving in America, he got a job as special delegate for the longshoremen’s union.” As he was “bashing heads together” one day, Johnson was observed by former boxer, silent film, and early sound film star, Victor McLaglen. McLaglen, known for his frightening role as the racist boxer Battling Burrows in D.W. Griffith’s haunting silent film Broken Blossoms (1919), then arranged a meeting with Johnson and some big film producers, securing his Swedish friend a Hollywood contract, according to the same report.

Like Mazurki, Johnson did not give up his wrestling career for acting. In fact, he used his Hollywood film appearances to boost his wrestling fame. His mentions in newspaper articles skyrocketed after his first film appearance in 1934. The Lowell Sun on November 19, 1937 describes a Toramania of sorts spreading across the nation: “Undoubtedly local wrestling fans have been reading and hearing about the success of Tor Johnson, 365 pound heavyweight champion of Sweden but few of them realized that they would see this huge grappling giant paraded before their eyes this season.”

This is no surprise, as Johnson appeared alongside such 1930s film icons like WC Fields in Man on the Flying Trapeze (1935), and his friend, Victor McLaglen, in Under Two Flags (1936). The same piece continues, “Tor Johnson is one of the mat game’s most colorful figures and is in demand all over the country.”

But his success was not limited to the U.S. Johnson even had a run of matches, main eventing at the legendary Toronto Maple Leaf Gardens, as demonstrated by classic posters put online by historian Gary Will, on the WrestlingClassics.com site.

In the 1940s, Johnson, like many wrestlers today, underwent a character change: he became the “Super Swedish Angel.” His Super moniker came because it seems “Swedish Angel” was as popular as the moniker “Nature Boy” in wrestling: another wrestler from Sweden, Philip Oloffson, already wrestled in the U.S. as the Swedish Angel, according to a 1950 article in the Long Beach Independent. Johnson decided to one-up him by becoming Super.

Tor Johnson in Plan 9 From Outer Space.

As he was getting on in age (and girth), Johnson lessened his wrestling appearances in the 1950s, and increased his film appearances. While The Super Swedish Angel did not star in A-list films like Mazurki did, he “made a big impression on me in his movie and TV appearances,” Maltin says. While Johnson might have starred in forgettable films in the 1950s, Maltin says he “was unforgettable in such movies as Ed Wood’s notoriously awful Plan 9 From Outer Space, (1959).

Not content with simply starring in one B-director’s films , Johnson took the lead role and top billing in another B-film director’s film, Coleman Francis’s The Beast of Yucca Flats (1961). This was his last role, since it was panned as one of the worst movies ever made.

“As with Bull Montana, I don’t remember ever hearing Tor utter a word onscreen,” Maltin recalls. “He was just a formidable presence.” Maltin is a staunch defender of Johnson’s legacy in film history: “I even have a plastic model of Tor sitting on my desk!”

Johnson died in 1971 from heart failure, but his legacy lives on today. The Beast of Yucca Flats has become a cult favourite after his death, thanks in large part to Mystery Science Theatre 3000. He was portrayed by George “The Animal” Steele in Tim Burton’s biopic, Ed Wood (1994). And he also appeared in the critically acclaimed alternative comic books of Drew Friedman, reviving The Super Swedish Angel for a whole new generation.

WWE FILMS FAILURE: DON’T BLAME THE PLAYERS….BLAME THE GAME

As for 21st century films featuring pro wrestlers, Maltin is less optimistic about their legacy in film history. In words that don’t bode well for Triple H and his new movie, The Chaperone, Maltin blasts WWE Films as a whole for reducing the overall acceptability of wrestlers in Hollywood in recent years. “WWE films haven’t done better because they need good stories and casts, first and foremost, to succeed beyond the core audience of hardcore WWE fans,” Maltin concludes.

RELATED LINK