George Kosti travelled an interesting road to the professional wrestling world. Born in the small town of Limerick, Saskatchewan, on April 25, 1930, George was raised on a wheat farm with ten brothers and three sisters. His mother passed away when he was four and his father was left to raise this large family on his own. As a young man, he constantly played hockey and also mastered the guitar, a hobby he pursued his whole life.

George’s reputation as a star hockey player in the region earned him the nickname ‘Teddy Ice’ because of his speed and strength on the rink. The Regina Pats, a premier junior hockey team in Canada, recruited him and the Chicago Black Hawks of the NHL expressed interest in his potential. Family obligations came first, though, and he returned to Limerick, ending a promising hockey career.

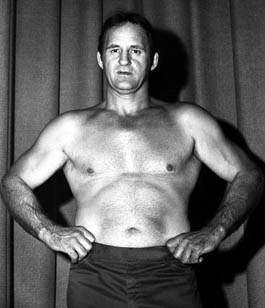

“Scrap Iron” Gadaski strikes a pose.

Big time hockey’s loss would be professional wrestling’s gain, as it turned out. George moved to Regina, began lifting weights, and was soon a YMCA instructor. He was one of the few weightlifters of the day in western Canada to bench press 500 pounds.

Professional wrestling caught George’s eye next. He approached Dave Pyle, a gym owner in Moose Jaw, Saskatchewan, who also promoted what was known at that time as “semi-pro” cards. Dave believed that George had the athleticism and work ethic to become a professional wrestler, and he was soon wrestling throughout Canada under his real name, mainly as a heel.

During the semi-pro off-season, George added to his stamina by working in lumber camps in far-north Slave Lake, Alberta. The camps attracted some rugged characters, and though George wasn’t confrontational, he had a few scuffles and always came out on top. He came home in 1957 and married Catherine Maskaluik, who would support him whole-heartedly throughout his ring career.

George then trained with the legendary Stu Hart in Calgary and admitted that, despite all his strength and stamina, he was pushed to the limits by the grueling workout sessions. Stu’s training fundamentals were crucial, as George entered the wrestling profession relatively late at 27. He weighed 240 pounds at the time and could trade holds or brawl with the best of them. He once broke his leg in mid-match and wrestled the rest of the bout, adding to his tough guy reputation.

A young George Kosti.

The United States beckoned, and George worked in San Francisco for Roy Shire, creating a reputation as a reliable worker against such stars such as Ray Stevens and Kenji Shibuya. He then headed south, wrestling in Georgia, Florida and North Carolina. During that time, he competed for the junior heavy weight championship against the incomparable Danny Hodge. Occasionally he was billed as “Killer Kosti” and generated significant heel heat in his matches. He was given the nickname “Scrap Iron” by a Georgia promoter, and it stuck for the rest of his career.

Fans of that day often attacked wrestlers and it was not uncommon for wrestlers to be injured in the melee. Also, there were opportunities for fans to step into the ring and “wrestle the wrestler.” George recalled one incident where he picked up a challenger and dropped him so hard, he thought the fan had broken his neck. Fortunately, the injuries turned out to be only minor.

Referee George Kosti listens to Nick Bockwinkel.

In 1967, George decided to try his hand in the AWA, but didn’t foresee a long stopover there. Initially, he wrestled TV matches at the WTCN studios on Saturdays as George Gadaski from Great Falls, Montana. Before long, though, Wally Karbo and Verne Gagne asked him to remain on a more permanent basis, wrestling as “Scrap Iron” Gadaski, refereeing and transporting and setting up the ring. George had grown fond of the Midwestern way of life, and with three kids in elementary school, decided that he wanted to settle down in one territory for awhile.

On the road a couple of hundred days each year, George traveled throughout the Midwest to regular AWA hotbeds such as Bismarck, Fargo, Duluth, Chicago, Davenport, Denver, Rockford and Winnipeg, and scores of spot shows in the upper midwest. Other wrestlers came and went, but “Scrap Iron” was a constant presence, always giving a good account of himself in the ring. Despite logging over 100,000 miles a year with the ring, he found time to work out during trips to maintain his peak condition. He had solid matches with major stars such as Billy Robinson, Verne Gagne, Ivan Koloff and Dr. X, and outings with newly-arrived talent that enabled them to showcase themselves to best advantage. George also enjoyed mentoring the younger matmen who trained under Gagne, such as Ric Flair, “Playboy” Buddy Rose, Doug Somers, Buck Zumhoff and Jim Brunzell.

Flair, in fact, had his first pro match against George in Rice Lake, Wisconsin on December 10, 1972. A far cry from the “Nature Boy” of later years, Flair weighed nearly 300 pounds and had plain brown hair. Ric himself tells it best: “I went to the ring not knowing what was going to happen. I wrestled 10 minutes to a draw — the longest 10 minutes of my life!”

Although George mainly wrestled the preliminary matches, fans could identify with his down-to-earth character and strong work ethic. The gimmick “Scrap Iron” was used throughout George’s long stay in the AWA, and cemented his reputation as one of the most identifiable wrestlers of that era.

George Kosti later in life.

George sometimes paired up with AWA regular Kenny Jay in the tag wars, often acting as the reception committee for new teams coming into the area. And in a change of pace, they even went over headline pairings the East-West Connection, Jesse “The Body” Ventura and Adrian Adonis, and the Texas Outlaws, Dick Murdoch and Dusty Rhodes, on several occasions.

In the late ’70s, George was allied with The Crusher in a memorable main event run against Super Destroyer and Lord Alfred Hayes. The angle was initiated on TV when Crusher threw down a challenge to the headline tag team, with a partner of his choice. Destroyer and Hayes accepted, and Crusher proceeded to pull George from under the ring, where he was posing as a utility/sewer worker. The feud drew sellouts in cities throughout the AWA territory.

George’s dedication showed in other ways. During a blinding snowstorm, the road from his home in Amery, Wisconsin to the highway was covered with more than two feet of snow. With a house show in Fargo, North Dakota still scheduled for that evening, George shoveled the road for more than five hours and despite closure of a number of main highways, ended up taking back roads to make the show in time. Another incident involved George falling asleep and driving off a bridge near Baldwin, Wisconsin. Miraculously, he survived when the truck landed on all four wheels about 30 feet below, and headed right back to work.

George was ultimately diagnosed with a brain tumor, and given only a few months to live. Always the fighter, he continued to work out even during chemotherapy treatment. The AWA honored George with a wrestling fundraiser in his hometown of Amery in April 1982, and that summer he made a final journey back to Saskatchewan to bid farewell to family and friends. Sadly, George succumbed to cancer on December 12, 1982 in St. Croix, Wisconsin.

“Scrap Iron” Gadaski, George Kosti, will always be remembered by his professional wrestling family as a true warrior.

A tribute from an old friend and CAC member, Mick Karch

To me, George Gadaski was one of the hardest working talents in the AWA. So many times, I would go on road trips from the Twin Cities to Milwaukee, Green Bay or Chicago, and invariably somewhere along I-94, we’d see the AWA ring truck with George at the helm. He would arrive at the arena hours in advance, help set up the ring, then get into the ring and wrestle or referee. Then at the end of the night, he would tear down the ring and more likely than not, hit the road in that ring truck, hauling ass to the next town to do it all over again.

Through all of this, he maintained a sense of humor, and an even greater sense of humility. It’s funny that when you talk to people who remember the glory days of the AWA, it’s not only the big stars that they remember. They will always include “Scrap Iron” Gadaski in their “whatever happened to … ?” questions.

That, to me, is a tremendous tribute. Sadly, I don’t know if George ever realized what his value was, and how appreciated he was.

RELATED LINKS