Gene Kiniski was so media savvy that he instructed this writer on what to write when the inevitable came, as it did on Wednesday, when cancer claimed the former NWA and AWA World champion. “This is what you say,” he proclaimed. “When you spent a buck to see Kiniski, you got a ten dollar value.”

Though he could play the press like a concert violinist, it took an ad-lib from the esteemed Dick Beddoes, one of Canada’s best-known sports reporters, to come up with Kiniski’s most famous nickname.

“I was being interviewed by Dick Beddoes, on a Hamilton TV station, and he said tonight we have Canada’s Greatest Athlete with us,” Kiniski explained in his chat with SLAM! Wrestling. “The phone lines lit up, and they wondered what made me the Greatest. Beddoes’ rebuttal was this: You have to wrestle Kiniski first, then if you can play basketball, hockey, golf, tennis, then you are a great athlete. You’d be lucky to lace on your boots. By referring to myself as Canada’s Greatest Athlete, it stimulated the audience. They hated that. I used to rub it in their face.”

Portrayed as a mean thug much of the time, Kiniski was in fact an intelligent, college-educated man, who would cram for his exam, which was usually riling up the fans wherever he was in the world.

“I used to leave hours or hours ahead, or even the day before, if I could just get on a radio program,” he explained. “I am an avid newspaper fan. … Every time I went to a town, I always read things about it so I knew what was happening locally — then I could just quote things.”

“Big Thunder” always knew to play to the audience. “Kiniski worked the system really well. I think that was probably 50% of his appeal was the fact that he had such camera control,” recalled “Cowboy” Dan Kroffat, a frequent opponent. “He had this mesmerizing interview ability.”

Canadian sportswriting royalty like Jim Coleman and Trent Frayne loved to write about him. “When a columnist runs into a dull, uninspiring day, the gloom can be dispelled quickly by placing a long-distance telephone call to Gene Kiniski, the sweetest Canadian this side of Guy Lombardo’s musicians,” wrote Coleman in 1968. Frayne described wrestling in its purest form, good versus evil: “Kiniski is always in the black corner, a really rotten man with a repertoire of eye gouging, throat stomping, crotch kicking and assorted other illegalities that drive the customers to paroxysms.”

Eugene Nicholas Kiniski was born of Polish descent on November 23, 1928, outside of Edmonton, to Nicolas and Julia Kiniski, with five other siblings. His father was a barber, and his mother, determined to improve the family’s lot in life, attended the University of Alberta, and after 11 attempts, she became an alderman in the City of Edmonton in 1963, a position she held until her death in 1969.

At St. Joseph’s High School in Edmonton, Kiniski played football and wrestled. On the mat, he won a few amateur wrestling titles, but in some cases, had trouble finding opponents to match up fairly to his size — he was more than six feet tall in high school, and over 200 pounds. On the gridiron, he attracted the attention of Annis Stukus, famed coach and scout for the Edmonton Eskimos, then of the Western Interprovincial Football Union. Instead of playing locally, Kiniski opted for a full scholarship at the University of Arizona, where he played left tackle for coach Bob Winslow from September 1950 until leaving school in January 1952.

Kiniski would then play parts of two seasons in Edmonton. “I was drafted by the L.A. Rams. I got a better deal to go up and play in Canada,” Kiniski recalled.

But in Arizona, he had been introduced to professional wrestling by the local promoter Rod Fenton.

“Hell, when I was still at the University of Arizona, I used to work out with the pros like Tony Morelli and Dory Funk Sr., guys like that,” said Kiniski, who admitted to being a little challenged by the switch from the amateur moves to the skills needed to be a good pro. “It was a little different. For me, working out with the pros, they showed me a lot of pro moves. Then in my early career, I’d get in the ring with a guy like Lou Thesz. He could look at you and hurt you. He just had so many moves. Just going along, you learn as you progress.”

In a 1969 interview, he admitted he didn’t miss football.

“Football is tougher. In this business [wrestling], you know where the blows are coming from. In football, you’ll be going one way after the ballcarrier and whap! Somebody will hit you from the blind side.”

Once he’d decided to turn to pro wrestling in 1952, he never looked back — “I know my ears will get thick, but if my wallet gets just as thick I’ll be satisfied,” he quipped after his debut match — and never said he was retired, though his last match was in 1994 in Winnipeg.

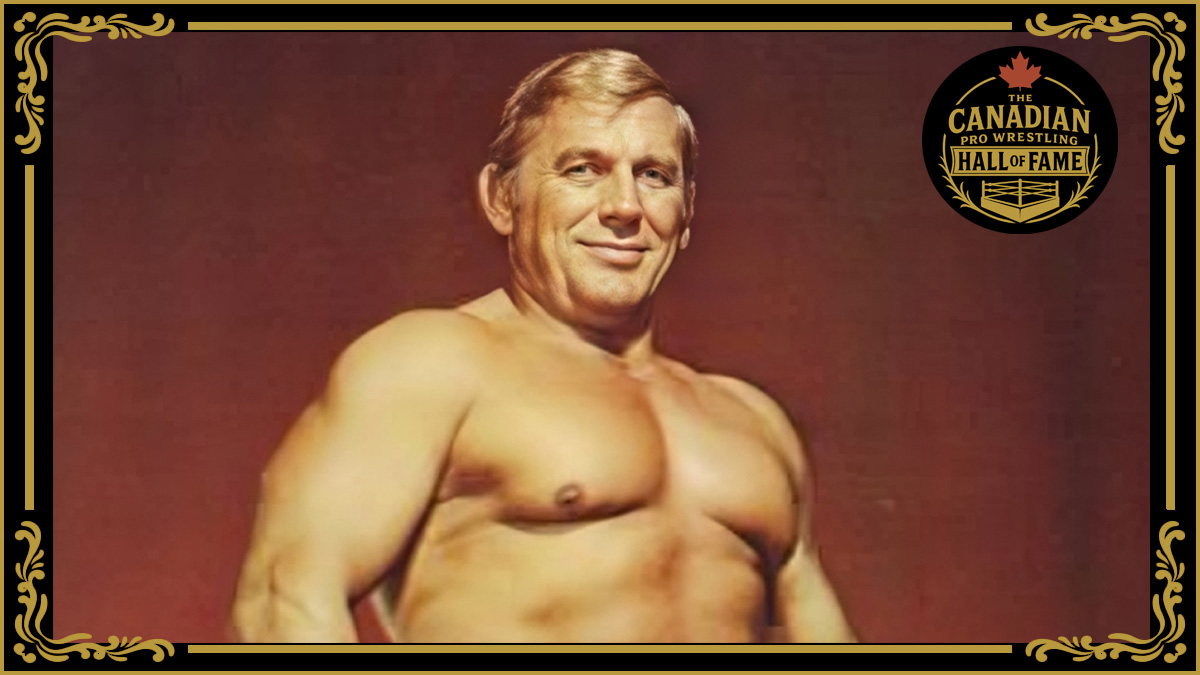

“I was a very, very distinct individual,” described Kiniski of his wrestling persona. “Very articulate, and my style was completely foreign to what is happening now. I was exceptionally strong and my endurance was unbelievable. And I’ve had a very extensive amateur wrestling background. Often imitated, but never duplicated.”

As a pro wrestler, there’s little Kiniski didn’t accomplish, though for a short while he wasn’t himself, he was Gene Kelly.

“That was in Texas. I got suspended in California so I used that name so I could wrestle in Texas,” Kiniski remembered about his time in 1956. “I was Gene Kelly, but everybody knew who I was.”

Around the same time, Kiniski first met up with the Canadian icon that would make his career: Whipper Billy Watson. The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation would air a bout between the two on a national basis, and it took off from there. They wrestled hundreds of times from the mid-’50s until Whipper’s injury ended his career in 1972.

“I wrestled him so many, many times. I think I wrestled him in every city and village in Canada. In fact, the first time we met in Newfoundland, my God, you couldn’t get near the airport. They had the largest crowd in the history of Newfoundland to welcome him,” reminisced Kiniski. “When I wrestled him, people went in there to see me beat. And I’d just go out — I had a flamboyant style. I’d just give them action, action, action because I’m a rough, tough son-of-a-gun. And as a result, we just drew so much money around, and I just kept on him, and on him.”

Suspensions and fines from the various commissions that regulated wrestling at the time were all part of his routine. Some of the transgressions were for in-ring roughness, altercations with fans, or the occasional bigger issue, like the 1959 arrest for assaulting a police officer who was policing the show.

The summer of 1957 saw Kiniski capture his first singles world title, as recognized by the Montreal promotion, when he beat Edouard Carpentier. In 1961, he was AWA World champion out of Minneapolis, and in 1964, he was a headliner against Bruno Sammartino for the WWWF World title. The WWA World title, based out of Indianapolis, was also his briefly in 1965.

It was in 1966, however, that he achieved his greatest fame, dethroning Lou Thesz on January 7, 1966 in St. Louis to claim the NWA World heavyweight title.

“Kiniski’s role as champion deviated from that of Thesz, and Gene comfortably delivered as a ‘bad guy’ night in and night out,” wrote Tim Hornbaker in National Wrestling Alliance: The Untold Story of the Monopoly That Strangled Pro Wrestling. “He could curb his methods to stay within the rules and still equal the viciousness with any growling heel, then shine against any number of favorites.”

While he was world champ, Kiniski lived outside St. Louis with his wife, Marion, and their two sons, Kelly and Nick. Given his dad’s notorious attitude, Nick said that he was trained not to say who his father was. “They say, ‘What’s it like to have a famous father?’ I don’t know — I’ve never had any other father,” said Nick Kiniski. “I just knew that my dad was a tough son of a bitch. I’d go watch him wrestle, sit in the stands and not say who I was for sure.”

At the 1968 NWA convention, wrestling lore is that Kiniski told off the promoters, saying that they were nothing more than pimps.

In a June 2009 interview, Kiniski said it was true.

“I tell them, the way they were treating me, fucking me with my payoffs. I told them off and fuck, they stopped using me,” he said. “They were fucking me on my back payoffs. I’m not that stupid. I know what’s in the house, what I should be getting and what their share is. All of a sudden you’d wrestle, then you’d have to wait a month to get your cheque and all that shit.”

He would drop the NWA belt to Dory Funk Jr. on January 11, 1969, in Tampa, Florida.

The irony is that around the same time as he was badmouthing the promoters, Kiniski was getting into the promotional game himself, buying out Rod Fenton’s share of the Vancouver, BC, company popularly known as All Star Wrestling.

“I had my family and I just wanted to stay in one spot so I could be with my family when they were growing up. So we bought Rod Fenton,” Kiniski said. “I knew Fenton for a long, long time. He was pretty well burnt out.”

Initially, it was Kiniski owning a third, along with Sandor Kovacs and Portland promoter Don Owen. “We were all in it together.”

To many fans, those were indeed the glory days of All Star Wrestling, with Ron Morrier as host and Kiniski always remembering to say hello to all the shut-ins at home. His stature helped bring in some truly great talent, though it didn’t last. And, according to some of the up-and-comers at the time, Kiniski didn’t want to let the spotlight go either — even if he could still dish out the punishment.

“I made the big mistake, believe it or not. I did an interview. You know how you start the interviews, ‘Let me tell you something, old man…’ The moment I said the word ‘old man’, Jesus, he must have chopped my chest 900 times. … he broke the vessels,” said “No Class” Bobby Bass. “We worked our asses off, and then Gene would walk in and beat the champion. ‘I’m Gene Kiniski and I’m going to beat you.’ Look at Jake. Jake was doing great out there, big babyface. Kiniski walked in and beats him, for no reason other than, ‘I’m Gene Kiniski.'”

Bass refers to Jake Roberts, who was not kind to Kiniski the (self) promoter.

“God, he was impossible. I get up there, and they weren’t drawing any money at all. That’s how I got there, because they had room for somebody because nobody wanted to be there,” Roberts said. “Moose Morowski, Moose and I, Moose basically led me through the process and made me a star, and got me over. In the process, we got to where the PNE was selling out, which they hadn’t done in years. At that point, Gene says, ‘Damn, I’d better come back in and wrestle again, they’re having sellouts.’ Of course, Moose put me over in a cage match, right in the middle, made me a star. Next thing, I wrestled Kiniski and he beat me two straight. I remember going to the ring that night, ‘You’re not going to do what everybody else does, lay down for the old fucking man, are you?’ Yep, two straight.”

Right until he sold out, Kiniski was the alpha male of the territory, even if he’d work as a bartender at his son’s tavern during the week.

“He killed it every fucking time. So why in the fuck would you do that, why would you murder your own business, just to grow testicles for yourself?” asked Roberts.

Kiniski explained the decision to sell. “Kovacs wanted to get out and he sold it to [Al] Tomko. Then to me, his idea of promoting wrestling was different. But then this gets into a business deal, and I’d rather not talk about it. I’m one of these people, my word is my bond. It ended up costing me a big bunch of money because of my stupidity. I trusted people. It just didn’t work out that way.” (Later, Kiniski sold to Tomko as well.)

Back on the road, Kiniski only lasted until the early ’80s as an active competitor. He was hardly gone though.

He was the special referee at the first Starrcade in 1983, when Ric Flair beat Harley Race for the NWA World title. “Being a referee was foreign to me, and there were two pro athletes in the ring. I let them do their thing. The fans came to see the wrestlers, not Gene Kiniski the referee. It was quite the experience for me,” Kiniski recalled in his chat session.

His two sons, Kelly and Nick, both had successful amateur careers as wrestlers before turning pro — Gene would work out with Nick’s Simon Fraser University wrestling team — and the connection to their world champion father was brought up often.

With his grouchy voice and memorable mug, it was natural for Kiniski to find some roles in movies and television as well. In 1990, he portrayed a violent biker cop in Terminal City Ricochet. “It was a humbling experience,” he said at the time. “I was completely out of my element.” Other roles included Paradise Alley and Double Happiness.

He made one last round of the Canadian media in 2001, when helping to promote Wrestling With The Past on The Comedy Network. Kiniski charmed a whole new generation of writers and TV hosts, including interviews with the Toronto Sun, Toronto Star and an appearance on The Mike Bullard Show.

The Cauliflower Alley Club honoured him in 1992, and, in 2004, he was inducted into the George Tragos/Lou Thesz Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame in Newton, Iowa (now in Waterloo, Iowa). “It’s a very, very big honor to be selected by your peers and to go in it with Dick Hutton, Lou Thesz, Ed ‘Strangler’ Lewis, Verne Gagne. To join such an illustrious group is quite an honor. I mean, how high you can get?” Kiniski told SLAM! Wrestling in 2004.

In 2008, the Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame in Amsterdam, NY, came calling, and he made the trek with his son Nick.

He downplayed the idea of putting one wrestler in a Hall of Fame above another, given that the business requires carpenters to make others look good.

“How can you put one wrestler above another, when so many contributed so much to the profession?” he asked. “Unless you were a part of it, and realized what happened, and what they went through — the injuries, physically, the time on the road traveling and stuff like that, and the profession was always being hammered by the news media. To me, I think that anybody who participated in wrestling, they’re strictly hall of famers.”

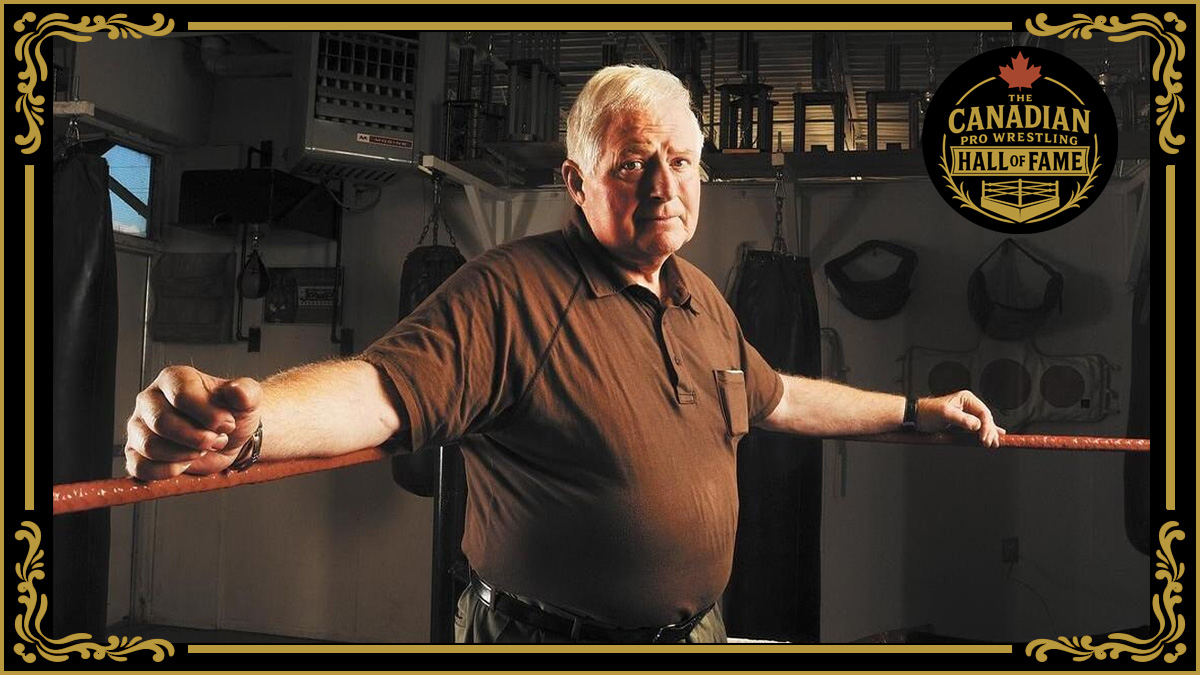

Over the past decade, Kiniski’s health deteriorated, in particular, his knees. But he was still a fitness fanatic. “Everyone calls it working out, but I call it doing my physiotherapy. I get on my bike and go for a bike ride. Then I still go swimming every Monday and Wednesday,” he said, offering up an oft-repeated gem: “The tragedy of old age is not that one is old, but one is still young.”

Congestive heart failure hospitalized Kiniski in early 2010, and he lost a lot of weight. The cancer which he had silently battled years before returned as well, eventually invading his brain. He passed away on the morning of Wednesday, April 14th, with family at his side.

While bed-ridden, he would complain about having to go out in such a way, but he never complained about the life he chose to live.

“I have one regret about the way I made a living — I wish I could do it all over again,” he said in 2006. “I had so many goddamn perks and all that. I just couldn’t see myself being a 9-to-5er, not that there’s anything wrong with it. I’ve been all over the continent, the world, and made a beautiful living. Hell, I’m still reaping awards.”