The oldest Guerrero brother, Chavo Sr., is certainly no stranger to prejudice. In fact, he’s had to deal with it for most of his life. But Chavo is a warrior and despite all the direct and indirect attacks he’s had to deal with, he was able to overcome it and add to the contributions of his family in the wrestling business. But it wasn’t easy.

In the early years, Guerrero was privileged enough to be able to travel across the United States and visit the various territories where his famed father, Gory, would work. However, he was not as privileged in other ways. It was not easy being a Mexican kid and growing up in the southern United States at the time. Even the school system in their hometown of El Paso, Texas, was still segregated.

Chavo Guerrero shows off all his titles in the Los Angeles territory in 1977. Photo by Mike Lano, WReaLano@aol.com

“I remember back then they still had separate ‘black’ and ‘white’ water fountains,” Guerrero said. “My brother Mando was a little lighter in skin colour and my skin was a little darker, so everyone started thinking I was Indian. I kept saying, ‘No man, I’m Mexican.’ There was a lot of prejudice back then.”

It didn’t get any easier for Guerrero once he started out in the wrestling business. But by then, he was so used to being discriminated against, that it didn’t bother him as much.

“I can’t say I was never discriminated against, especially in the south,” Guerrero said. “The promoters would discriminate every once in a while, but it was never a direct hit. I think I was discriminated against more by the fans than anyone else. I found that they were more prejudiced against me in the business because of my size. But I was still given a lot of chances and a lot of it had to do with my dad. Nobody had anything bad to say about my dad. It was very hard for me to deal with. As a heel, you have to go out and take anything, because the fans are going to hate you regardless, so you have to get used to it, but if they hate you as a babyface, it was more difficult. My dad always told me that as long as I get the best match of the night, at least I’d know I did a good job.”

For someone outside the business looking in, it can be very hard to determine what sort of behaviour is prejudice and what’s not. Guerrero did mention that when he first started out, the promoters themselves were not as direct when it came to racial discrimination. However there were certain situations that Guerrero not only dealt with, but also witnessed, which he made him feel somewhat uncomfortable.

Chavo Guerrero and his America’s Tag Title partner Raul Mata are interviewed in L.A. in 1976 by Gene Lebell. Photo by Mike Lano, WReaLano@aol.com

“In Dory Funk Sr.’s promotion in Amarillo, Texas, there was a wrestler by the name of Gordo Chihuahua and they had a talk show with this guy on it and he would come out wearing a poncho and a sombrero and whenever the interviewer asked him questions, all he would say is, ‘Si, si’ and I remember watching that on TV with my dad and I could see that he wasn’t impressed and I really didn’t like that either,” Guerrero said. “And then in the WWE, they brought in Juventud Guerrera and Guerrera means ‘the war’ in Mexican and he would go around with his group that he had and ride lawn mowers to the ring and it looked like they were trying to say that most gardeners are Mexican. But when you’re given a gimmick, no matter what it is, you have to do your best to get that gimmick over, otherwise it won’t work. It’s the only way you can make any money.”

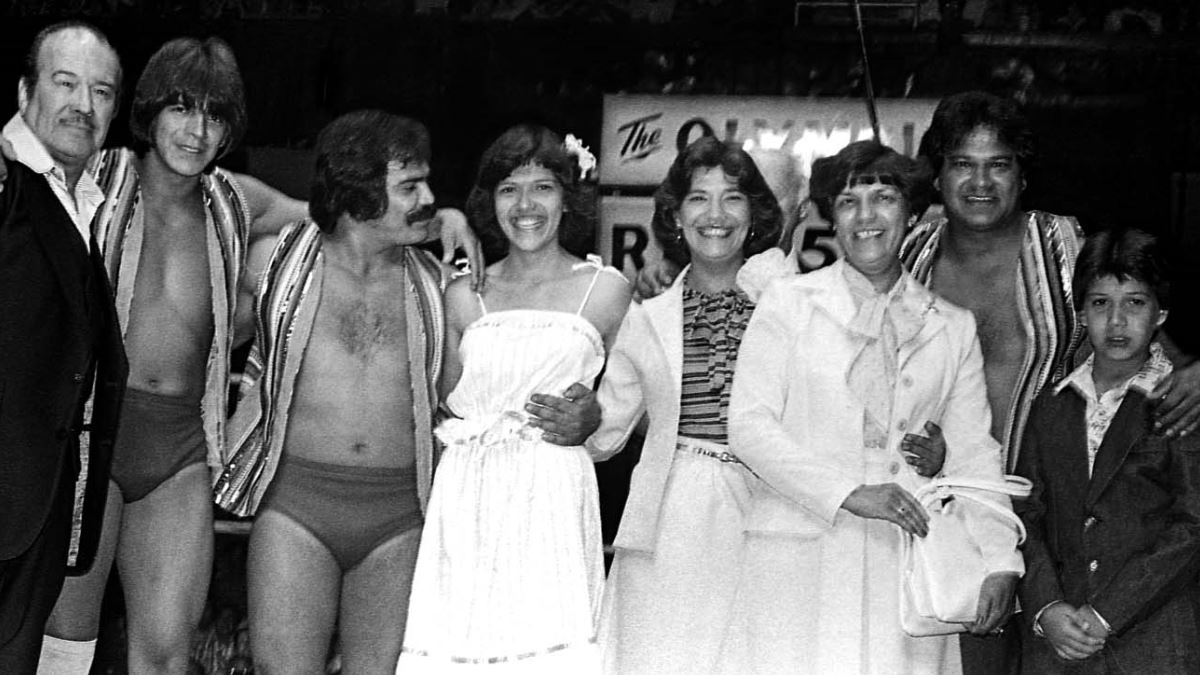

Chavo Guerrero and his brother Hector. Photo by Mike Lano, WReaLano@aol.com

Perhaps the one thing most commonly associated with the Mexican heritage in wrestling is the mask. Masks are sold in arenas all over Mexico and the superstars there wear them as if they were trophies. So it’s understandable how uncomfortable Latino wrestling fans would be when they see one of their favourite wrestlers have to put their mask on the line in a match. The most recent evidence of this is last year’s angle between Chris Jericho and Rey Mysterio, where Mysterio had his mask on the line against Jericho’s Intercontinental title. Fortunately, Mysterio was able to hold onto that mask and win back his title. But if the circumstances were different, Guerrero says it would not have been good business.

“Rey Mysterio without that mask would not be Rey Mysterio,” he said.

Guerrero says there are also some positive stereotypes. When his son Chavo Guerrero Jr. and late brother Eddie did the Los Guerreros gimmick in early 2003, some may have seen it as just another stereotype, but it did get over and it got over very quickly, because according to Chavo Sr., the right two guys were used to get that gimmick over.

“Timing is everything in this business. Timing is the essence of success in wrestling,” Guerrero said. “If a gimmick is used at the right time, with the right guy to pull it off, then people are going to go crazy for it. I think Eddie and Chavo got that gimmick over, because not only were they great performers, but they could also back it up in the ring and if the guy doing the gimmick can’t back it up in the ring, I don’t think the gimmick would last too long. The fans accepted it. A gimmick won’t get over on its own. The guy doing the gimmick is responsible for getting it over.”

Nobody can really question or speak negatively of certain wrestlers, no matter what ethnicity they belong to. And Chavo Sr., along with his brothers, father, mother, son and sister-in-law have all proven that the name Guerrero is not only synonymous with Mexican wrestling, but it’s synonymous with wrestling in general.

“We’ve had our problems in the past, but what family hasn’t. But when someone outside the family comes and tries to start something with one of our relatives, we’re all going to gang up and beat the s**t out of them,” Guerrero said. “We respect each other and we’ve always been close. We’re Guerreros and we’ll never leave this business.”

Guerrero will be making an appearance at the Wrestle Reunion show, hosted by Bill Apter, which runs all weekend from January 29-31 at the LAX Hilton in Los Angeles, CA.