By GREG OLIVER & STEVE JOHNSON – SLAM! Wrestling

Karl Von Hess, who died this morning, August 12, 2009, at the age of 90, after a long battle with Alzheimer’s disease, made his name heading to the ring in a full-scale Nazi guise in the uneasy years after World War II.

With American patriotism in full swing, he would enter arenas with a galling Waffen SS appearance and a “Sieg, Heil!” salute. No wonder Von Hess, a master of minimalism, was shot at, stabbed, attacked, and burned en route to becoming a white-hot heel in the late 1950s.

“Karl Von Hess was absolutely wonderful,” said Ted Lewin, wrestler-turned-author and illustrator in The Pro Wrestling Hall of Fame: The Heels. “He was very special because he didn’t do a heck of a lot to make people angry at him. All he had to do was kind of keep turning and looking at the audience, and the audience would boo, and then he’d turn and look at them again.”

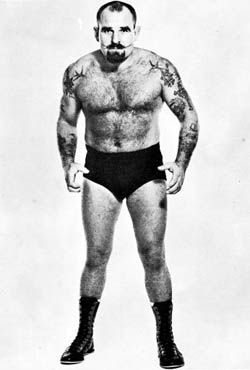

Karl Von Hess

Johnny Rodz, a member of the WWE Hall of Fame, said Von Hess was his favorite heel. “He was the meanest. Who the heck comes to the ring and breaks the steps before you get in the ring? What gives a guy that reason?” Rodz pondered. “Anybody who sees the steps before you walk into the ring, and you want to break them before you go into the ring, who the heck wants to deal with him? He must be the baddest guy in town!”

Francis Faketty — he later officially changed his name to Karl Von Hess — was born in Michigan in 1919 to Hungarian immigrants, and raised in a gritty, working class section in south Omaha. His early life was not easy — his accent made him prey for bullies at school and he coped with an abusive father who drank too much and took out his violence on Von Hess’ mother.

A terrific athlete, Faketty trained himself to swim in the swift currents of the Missouri River. “He was just an incredible human specimen for somebody who never went to the gym,” his son, John Von Hess reflected in The Heels. “He used to swim across the Missouri River, steal watermelons, and bring them back with him. You can imagine what kind of feat that was.” He later taught swimming and worked as a lifeguard — kids at Morton Park Pool in Omaha called him Tarzan — and started boxing and wrestling competitively.

“He was so well built, they used to call him Tarzan. He had an incredible physique,” recalled Mad Dog Vachon, another long-time Omaha resident.

After serving aboard the USS Montpelier in World War II, where he was a part of the Underwater Demolition Corps, the forerunner of the Navy SEALs, Faketty kicked around carnival and athletic training shows and worked with forgettable gimmicks like Mara Duba, the South American Assassin, who had a pet lion.

He was in the Pacific Northwest in early 1955, at the same time Kurt Von Poppenheim was employing a less sinister German gimmick in the territory. When he went to the Carolinas that fall, he underwent a makeover to Von Hess, became an immediate sensation as an out-and-out Nazi, and was a key player in the talent movement between the Carolinas and Vincent J. McMahon’s Washington office on the East Coast. He spoke forcefully, spewing hate, and even and even muttered a little German, like any good storm trooper. Doctored publicity psoters showed him with Martin Bormann and Adolf Hitler.

“Listen,” he explained years later. “It was right after the war and I had tried everything. I played different characters, and then I came up with this gimmick of Von Hess and I played it right to the hilt.” Despite the fact he could go toe-to-toe with almost anyone, Von Hess didn’t use his grappling skills. He was hardcore — he kept wire in his trunks to choke people when he couldn’t use the ring microphone to do it. He threw chairs.

“In the ring, you couldn’t imagine Von Hess with any sense of humor at all, yet he had a very funny sense of humor,” Lewin said. “Frank would live that, he would refuse to sign autographs and things like that, so he would keep that character out of the ring to a certain degree.”

Von Hess’ finishing move was known as the hangman or hangman’s noose. Back to back with his opponent, Von Hess would reach up and back, grabbing his foe under the jaw, and then lean forward. Though his victim was actually supported by Von Hess’ back, it looked like vicious hold that would really hurt.

He and “Wildman” Jackie Fargo engaged in a series of violent brawls on TV in 1956 that drew howls of protest to the District of Columbia Boxing Commission. “I stuck a cigar right in his face,” Fargo recalled with a laugh in The Heels. “I was really upset at him and something was said and I just said, ‘Screw you!’ and pushed that cigar in his face. If I had it to do over after it was done, I wouldn’t do it. But he walked away from it … He was a very good wrestler, very, very good. Nice fellow too. He could wrestle and he was pretty tough, too.” So great was the outrage that McMahon calmed matters in The Washington Post by breaking the protection of the business.

“Von Hess is no Nazi. He uses that silly salute to point up the act that he is the villain,” McMahon acknowledged in a candor rare for the age. Still, Von Hess set the Baltimore-Washington territory on fire in 1956 and 1957. A three-match series in Washington against frequent foe Antonino Rocca culminated in an outdoor show at Griffith Stadium in 25 years; McMahon publicly credited Von Hess as Washington’s top draw since the heyday of Jim Londos a quarter-century before. In New York, the state athletic commission directed him to put tape on his boots to hide a swastika. “Too much heat,” explained Vachon. “It was a dangerous job. He could get stabbed, or shot, or anything.”

In the 1960s, Von Hess cooled off and later said he felt the WWF was anxious to put him out to pasture; he had a brief stint with a version of the world title in Cleveland in 1963, but that was quickly dropped. He worked in several other territories, including Tennessee and Hawaii, left wrestling in the late 1960s, and operated trailer parks and other businesses with his wife Lenore, who died in 2005 after 53 years of marriage. In recent years, Alzheimer’s disease sapped his memories, pleasant and unpleasant.

Funeral arrangements are not known at this time.