Albert “Ole” Olsen was not a name known much outside the Manitoba wrestling circles. Yet, with his passing on Thursday, August 21, 2008, at the age of 85, many of the much more famous people that he helped break into the business, shared their memories of him.

“Ole Olsen, at the time I met Ole, he was one of the best wrestlers in Winnipeg,” said Al Tomko, who would work many territories, and later promote in Winnipeg and Vancouver. “He was a champion. If it wasn’t for Ole, there would not be a lot professional wrestlers. He broke in more people than I can think of.”

Some of the names no longer around include George Gordienko, “Iron” Mike Koncur, and Roy McLarty.

Gord Nelson, who would become a star in England, met Olsen at the YMCA, where he learned amateur wrestling. “He was tough competition, but he started me off and everything,” said Nelson, calling Olsen a tough teacher. “He was pretty strict.” (Later, they would marry women who were cousins.)

Tomko was another of those youngsters on the mats of the YMCA who caught Olsen’s eye. “He more or less started me out in wrestling,” said Tomko. “I started working out with him at the YMCA. If you’re good, people notice you, right? That’s it.”

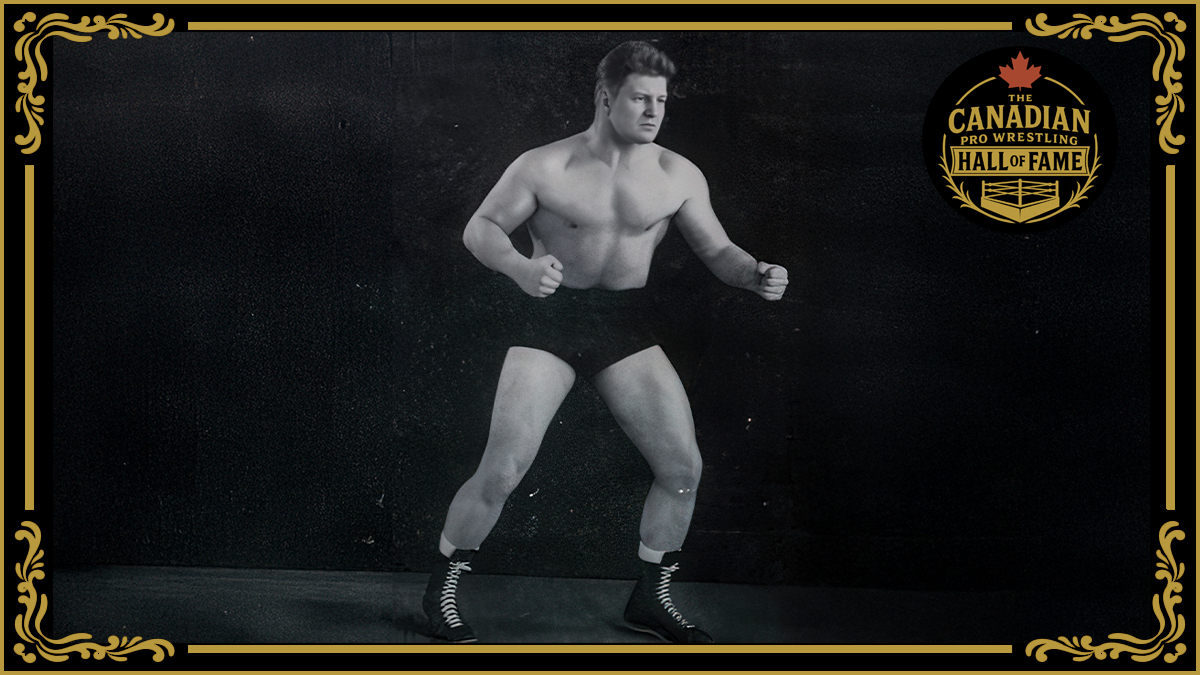

Born September 10, 1922, in Lac du Bonnet, Manitoba, Albert Olsen grew into a 5-foot-9 lightweight, who worked at anywhere from 209 to 228 pounds. His amateur wrestling career really began around 1945, when he trained under Harold Nelson at the Winnipeg Downtown YMCA. That same year, he played for football’s Winnipeg Blue Bombers, but did not stick around more than a season. Instead, Olsen found employment with the Winnipeg Fire Department, where he would work until his retirement.

In 1948, Olsen also competed for a spot on the Canadian Olympic team, losing to Fernand Payette in the finals.

In 1950, Olsen took a three month leave of absence from the fire department to train to be a professional wrestler in Minneapolis under Wally Karbo and Tony Stecher. Not only did he turn pro that year, with his debut coming at the Winnipeg Civic Auditorium on October 4, 1950 (a draw against Caifson Johnson), but he also married his wife, Joan.

Olsen was a regular on shows around Alex Turk-promoted shows around Winnipeg for years. When he had enough time off from the fire department, he made trips to Calgary, Minneapolis, and even Toledo, Ohio in 1952.

“A comparative newcomer to the professional mat world, Ole Olson of Western Canada is advancing by leaps and bounds and is definitely one of the brightest prospects in wrestling at the present time. The husky, sandy haired Ole hails from the wrestling conscious city of Winnipeg, Canada, ” reads The Ring in October 1952.

A young Moose Morowski, working under variations of his real name Stan Mykietowich, worked with Olsen many times. “He was really, really stiff,” he said with a laugh. “He was the old-school, everything was real solid. He was a hell of an athlete. This was an old Stu Hart type. … He was a really tough fart. I’ll tell you, he’s the type of guy, if you weren’t in good shape, he’d take no mercy on you.”

Turk and Olsen had a falling out, and Olsen stopped wrestling for a time before becoming a promoter himself. “When he was wrestling for Turk, he got really disillusioned with the professional side, and just went back to doing local independents in Winnipeg,” explained Western Canada historian Vern May (wrestler Vance Nevada). He denounced his professional status, and ran “semi-pro” shows under the Norland Wrestling Club banner. “That was kind of slick marketing by the Winnipeg guys because by saying it was semi-pro, then they didn’t have to pay commission fees,” said May.

The Norland Wrestling Club ran shows at the Winnipeg Roller Rink and in Grand Beach. After the 1959 season, Olsen sold his ring to Al Tummins of the Madison Club and ceased his own promotional efforts. Following the sale, Olsen would become a regular with that club. It wasn’t long before he was again riding a wave of success.

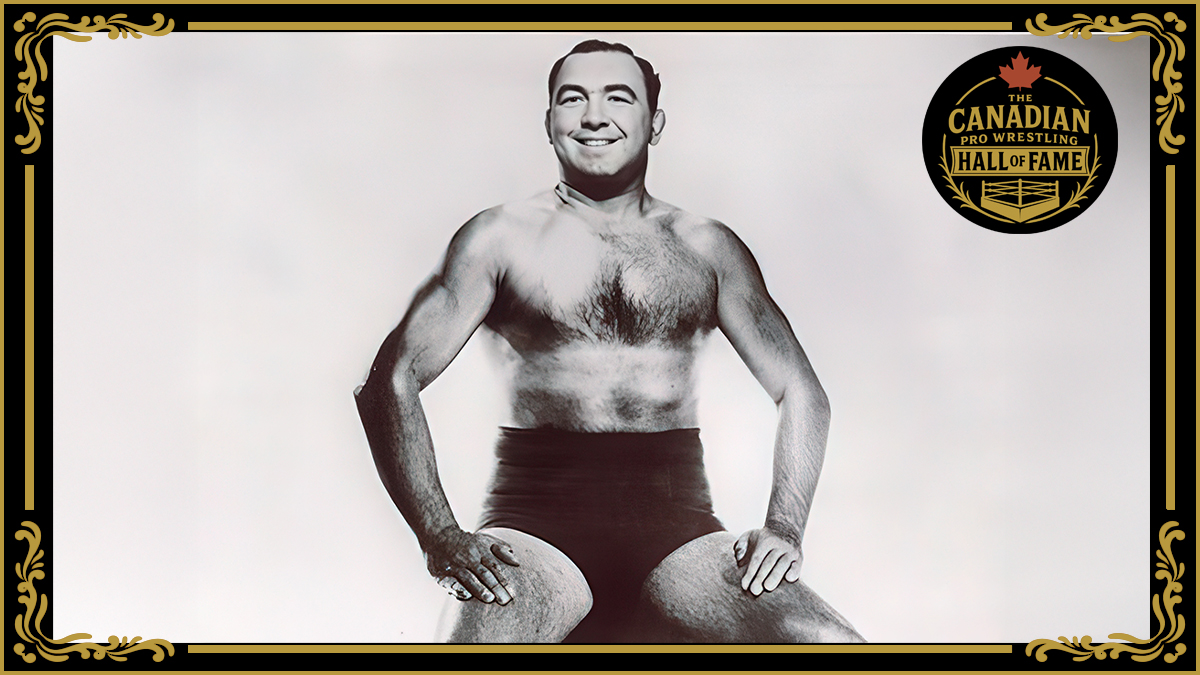

In mid-1960, Olsen teamed with Frenchy Champagne to win an eight-team tournament for the vacant Madison Club tag team titles with a win over Bob Brown and Bill Kochen. Their title reign lasted for almost a year, seeing Champagne and Olsen become recognized as one of the most dominant twosomes of that period.

“At the time, when he was active, he was legendary,” explained May, who got to visit with an aging Olsen long after his in-ring career ended in the late 1960s. “I’ve been over to his house a few times. He always had a real good number of stories to tell, he’d pull out the photo albums from the Madison Club. When I’d gone over there, he was up on a chair, he was maybe 79 years old, and he was up on a chair tearing the moldings off his ceiling. I’m thinking, ‘You’re the only 79-year-old guy that’s still active enough to be up there doing that kind of work.’ He looks at me, and he goes, ‘You know, it really sucks getting old.'”

After retiring from the fire department, Olsen was in good health, said his wife, Joan. “He had a massive stroke on Wednesday last week, and died Thursday night. But he’d been in good health up until that time,” she said.

David Olsen, one of three sons and a daughter of Ole and Joan, said that firefighting always came first to his father, and wrestling was second. The dual careers really didn’t affect them, he said. “I think he was just a normal dad.”

Albert “Ole” Olsen, who died Thursday, August 21, is survived by his wife, Joan, his sons David, Eric and Paul, and daughter Ada, as well as six grandchildren and five great-grandchildren. He was cremated and the family has held a private ceremony.