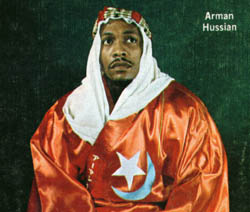

Usually, when someone passes on, friends tell stories about their lost colleague that they knew so well. However, in the case of the Arman Hussian, who died in a Dallas nursing home on New Year’s Eve, December 31, 2007, his co-workers can only admit to knowing the man a little.

A well-traveled wrestler in the 1960s and 1970s, who worked both as a good and bad guy, the tall, well-built Hussian transformed into a heel manager in Dallas for World Class Championship Wrestling in the early 1980s as the promotion began to get national exposure. He is best known, perhaps, for using a whistle constantly at ringside, driving the fans and his charges to distraction.

“The articulate, dignified, well-educated Arman Hussein was an immediate hit with fans. A star of the 1960s and 1970s, Hussein’s confident persona and cool demeanor led him to success in several territories,” wrote Julian L.D. Shabazz in Black Stars of Professional Wrestling.

Hussian is a bit of an enigma.

Is his original name Mike Harmon? Mike Barber? He definitely changed his name legally at some point to Arman Hussian, to better reflect his Muslim religion.

Was he from the Sudan, as billed? Unlikely. Alabama seems to be his original home, though he lived in Texas for at least the last two decades.

His age? “His driver’s license that he showed me gave a birth year of 1946, but everyone I knew said that was a work. However, Texas driver’s license records indicate his birth was July 3, 1946,” wrote his friend Jeff Cunningham on the Wrestling Classics newsboard.

Did he have family? An old magazine story, full of great kayfabe of the day, says he was separated from a wife and had two sons in Britain. That doesn’t add up either, said Skandor Akbar. “The thing about Arman is, and I was kind of close to him, and probably as close as anybody, as anybody he’s known, but he never made mention of any private life, or anything like that,” Akbar told SLAM! Wrestling.

According to the Rahma Funeral Home in Dallas, a friend organized all the funeral for Hussian, and no family at all was involved. Hussian was buried at the Muslim cemetery in Krum, Texas.

So, what do we know?

His career appears to have started about 1958. He was 6-foot-1, weighed about 240 pounds, and had a great physique. Often, he would sport a thin mustache and goatee, with a shaved head. He wasn’t overly muscle-bound, such as Sailor Art Thomas, another pioneering African-American wrestler. Instead, he had an athlete’s body that he took very good care of.

“Hussian’s physical statistics are staggering,” wrote Lou Sahadi in June 1967 Wrestling World article. “His biceps measure 19 1/2 inches; his chest 50 1/2 inches; his neck 18 inches; his thighs 25 inches and his calves 17 inches. He developed his body from years of exercise and lifting weights. In wrestling circles, he is considered one of the strongest performers on the circuit.”

At some point, he decided to create the character of Arman Hussian, which was misspelled by various promoters as Armand or Hussien. The name first starts appearing in 1959 in Minneapolis, which was in the process of becoming the well-known American Wrestling Association. Hussian’s time in the midwest — which definitely took him north of the border to Winnipeg, lasted until mid-1960. Then it was off to Michigan, where he reigned as Michigan state tag team champion with Tiny Tim Hampton.

Hussian was billed as being an exotic foreigner from Sudan, who schooled in Britain. A clotheshorse who dressed the part, he became known for living his gimmick.

John Quinn, who would win a title from Hussian in Seattle in 1974, remembers the British accent. “He never dropped it, even among the boys,” said Quinn. Jose Lothario, who would battle Hussian at the end of his career, concurred. “He tried real hard, and could get by with it. He sure did.”

“He was a strange dude, a very strange character,” Seattle promoter Dean Silverstone told SLAM! Wrestling. Earlier, Silverstone had posted his memories on the Cauliflower Alley Club website. “He was a real rare bird, even for this business. He NEVER broke kayfabe, even in the dressing room. He was billed as having graduated from Oxford University and was from the Republic of Sudan, but, although extremely well versed and educated, I’m pretty sure he never attended high school and lived most of his life (when not on the road) in Dallas.”

By the summer of 1965, Hussian was in the Pacific Northwest, and polished enough to carry a title. He held the NWA Pacific Northwest tag team belts with fellow hero Shag Thomas, having defeated The Mad Russian and Stan Stasiak. In 1966, he was in New York working the WWWF as a babyface wearing colorful, patterned trunks, often teaming with perennial heroes Bruno Sammartino and Bobo Brazil. Another trip to the Pacific Northwest would follow.

In Los Angeles in late 1967 to mid-1968, Hussian would work as a solid mid-card wrestler, but having had success elsewhere, believed he should be elevated. So Hussian took the promotion to court, with a complaint to the State Fair Employment Practice Commission in 1970.

Teaming with Sam Lumumba in the action, Hussian claimed to have had to go on welfare because he made so little money. “We had to go on welfare or we would have starved,” Hussain told the Los Angeles Times, and claimed to have only made $600 for the entire year according to the Times article. “People want to see us at the Olympic Auditorium,” Hussain said. “but the promoters won’t let us wrestle.”

Mike LeBell, manager of the Olympic Auditorium in L.A., said the charges were “completely untrue” in the same Times story. “Their saying that they are not being given work because they are black really burns me up,” LeBell said. “The reason they have not been given main event matches is that they are not of main event caliber.”

Other territories never had a problem with him. “I found him in Florida,” said Silverstone, “and I said, ‘Do you want to come to Seattle and work for me?’ He said, ‘I’ll be there.’ That was the end of it. We got along famously.”

Hussian and Abdullah the Butcher were paired as a heel team in Vancouver in 1968, even holding the NWA Canadian tag belts, beating the formidable duo of Haystacks Calhoun and Don Leo Jonathan for the belts. At times later in his career, Hussian would work as Hussian the Butcher, sometimes leading to a run with Abdullah.

The early to mid 1970s would see Hussian at his peak as a performer. He had a long successful run in the Gulf Coast region in the southeastern U.S. “Hailing from the Republic of the Sudan in Northern Africa, Hussein was an instant hit with the fans,” wrote Mike Norris on Kayfabe Memories Gulf Coast section for 1972. “With his curled toe boots and his ‘Camel Walk’ that he did upon entering the ring, he was a sight to see. He was just as exiting inside the ring as well. He finished most of his opponents off with a ‘Camel Roll’, a kind of somersault on top of his opponent and then a ‘Desert Crab’ (a version of the Indian Death lock).” He would reign as Mississippi Heavyweight champion on three occasions as a babyface, and feud with the likes of the Spoiler, the Wrestling Pro, and the team of Rip Tyler and Eddie Sullivan.

In Silvertsone’s Superstars of Wrestling promotion, based out of Seattle, his goal was to bring in fresh faces for the fans to see. Hussian was the only one who had worked the territory before, and would be the promotion’s first champion. John Quinn took the belt away from him. “He was quite the athlete, smaller than me. Took it well when he lost it in Seattle,” said Quinn.

Arizona would follow Seattle for Hussian, where he was the first Western States Heavyweight champ, and then to the Oklahoma-based Tri-States promotion, where his most famous run would occur. Hussian beat Bull Ramos for the North American Heavyweight title on July 29, 1974. A black man with the territory’s top title, representing Oklahoma, Louisiana and Arkansas was very radical at the time; Tom Jones had already shown that an African-American could draw in the territory, but he was never the champ.

It all set him up for a lengthy run with the hated Skandor Akbar over the belt. Akbar had only run across Hussian once or twice before tangling, but would be instrumental in much of the rest of his career.

“You could probably say that I was an intricate part with him in his career. The run that we had was one of the best runs he ever had,” said Akbar.

“It was kind of a slow time of year,” he recalled. “My goodness, we went out to Vicksburg, Greenville, Greenwood, all those, Jackson, and we sold them out for five, six weeks in a row. I made him a babyface, a good guy.

“At that time, we had more towns than anywhere in the country. We had two, three towns every night. But if you were working on top, you might be in Tulsa one night, then have to go to New Orleans the next night. Some guys stayed on the bottom, the middle and the top. Really and truly, nobody thought we’d do the business that we did. We did fantastic business.”

Hussian’s in-ring moves and gimmick made it a little difficult, Akbar said. “Nobody really wanted to do anything with him [because he was so big] for obvious reasons. His style was so much different. But you know, I adapted to that. I had so much heat. What we did was just a natural thing, and the people loved it, the people loved it.”

Arman Hussian delivers a jab to Chuck Karbo in Arizona. Photo courtesy Bob Leonard

The rest of the 1970s read like a road map for Hussian: Tennessee and Lousiana in 1977, Puerto Rico in 1978. He also worked in Salt Lake City, Hawaii, and Japan at various times in his career.

Word is that Hussian loved the road.

“I think he was one of the most traveled guys of the 1960s. … I don’t think there was a place he didn’t work,” said Silverstone.

“I have been well accepted both professionally and socially since I have been in the U.S.,” beamed Hussian in the Wrestling World article. “I have acquired many friends here in many different cities.”

That wasn’t the half of it, said Akbar.

“The one thing that you could go to the bank on, he always had a place in different towns, some particular person — he or she — where he could go and spend the night. I don’t know of any meals he ever paid for when he was on the road! He knew everybody!” laughed Akbar, launching into a story about how they both loved blues music. As the south’s most hated man, Akbar couldn’t go exactly go buy an album of, say, Bobby Blue Bland. So he turned to Hussian. “‘I need one of those records.’ I’m not going to go into those black record shops in Vicksburg. Shit, they would have killed me.” Over the years, Akbar would meet a lot of blues players, including Fats Domino. “You know, most of them knew Arman Hussein, the ones that I talked to.”

By the time the 1970s turned into the 1980s, Hussian had settled in the Dallas area, and was a regular part of the Von Erich-run promotion. At first he was a low-to-midcard wrestler, but he made his mark — at least according to Scott Casey. “When you stop to think about it, we were all a little crazy to do some of the things we did,” Casey told Scott Teal in a Whatever Happened To … ? interview. “Arman Hussein and I wrestled on TV. He had a long fingernail on his right hand. When we locked up, his fingernail went into my cheek, all the way to the bone. We were only thirty seconds into the match. I picked up a chair and beat him to death with it. I was so mad. I had my girlfriend take me to the hospital. That was on my 33rd birthday.”

According to Cunningham, a car accident ended Hussian’s in-ring career. “Arman’s career was ended when he had a very bad car wreck in the early 80’s and broke his left hip,” he wrote at Wrestling Classics. “It became infected and he very nearly died, from what he told me. However, he never told me that it was a car wreck. I got that from the business. He worked everyone, even the boys. Told everyone that Roddy Piper and Jos LeDuc did it to him in the ring.”

In 1982, Hussien formed a faction with Gary Hart known as “H&H Limited” in World Class. They would co-manage the likes of The Great Kabuki, Magic Dragon, Bill Irwin, Bugsy McGraw, The Superfly (Ray Candy), Frank Dusek, Checkmate, The Spoiler, and more. Then Akbar was thrown into the mix as another heel manager, with King Kong Bundy jumping from H&H to Akbar. Hussian brought in The Great Yatsu from Japan who beat Bundy in a loser-leaves-town match.

“They called themselves H & H, Hart & Hussein. I had been there for a while, and had been over in Mid-South for Bill [Watts]. What had happened, I had started working both territories there for a while, and I went over to World Class,” recalled Akbar. “That was a good time, and things were really beginning to fuel for World Class at that time.” As Hart faded out, Hussian was the prominent face. But at 1983’s “Star Wars” megacard, Hussian lost his own loser-leaves-town match, losing to Kamala despite teaming with Tola Yatsu and Mike Bond.

Arman Hussian on the way to the ring. Photo courtesy Bob Leonard

After that, Hussian faded from the wrestling radar. He declined to attend the annual “Shootouts” at local establishments hosted by Red Bastien, where the Texas wrestlers reunited.

Akbar did manage to entice Hussian out to one show in 2003 in Garland, Texas, that he ran. “I had Kamala here, brought him over here and everything. Arman came to that show, but he had changed. He’d lost so much weight, and he walked right by me, and said, ‘Hey!’ I turned around and I knew who he was. That’s the last time I seen him, and we talked and talked. He had a good time. But as far as knowing that much about him, I don’t know. It’s speculation.”

What is known about Hussian’s last decade or so is that he was really, really into blues music, and frequented blues clubs around town. He was so well known in those circles that a tribute/fundraiser is being held for him this coming weekend.

“He was an avid lover of the blues and came to our Jams nearly every week until he got ill. He would often bring us food. I guess he thought we didn’t eat enough,” wrote musician Terry Montgomery on the Wrestling Classics board, inviting people to the Saturday, January 12th event at the Mardi Gras Cafe, 2720 N Stemmons Fwy, in Dallas (214-634-9669), with a 3 p.m. Start. It is a memorial benefit to help pay Hussian’s funeral costs, and the lineup will include RL Griffin, Ernie Johnson, Big Charles Young, Rob Donovan, Big Jim Wells and the Nightowls, Perry Jones and Friends, Hash Brown, Christian Dozzler, Anson Funderburg, and Joe Jonas, Tutu Jones, and, a “Armand Hussein Open Jam.”