There’s a reason that “Hustler” Rip Rogers is still involved in training wrestlers today — in an ego-driven business, he always kept the right perspective, listened to the veterans and was a professional. It wasn’t something he saw with all the so-called superstars.

“If you can work, you can pretty well get a job anywhere. Sometimes, you’re a little too good, and there’s a jealousy factor in there, because a lot of stars are just rotten,” he told SLAM! Wrestling a while back.

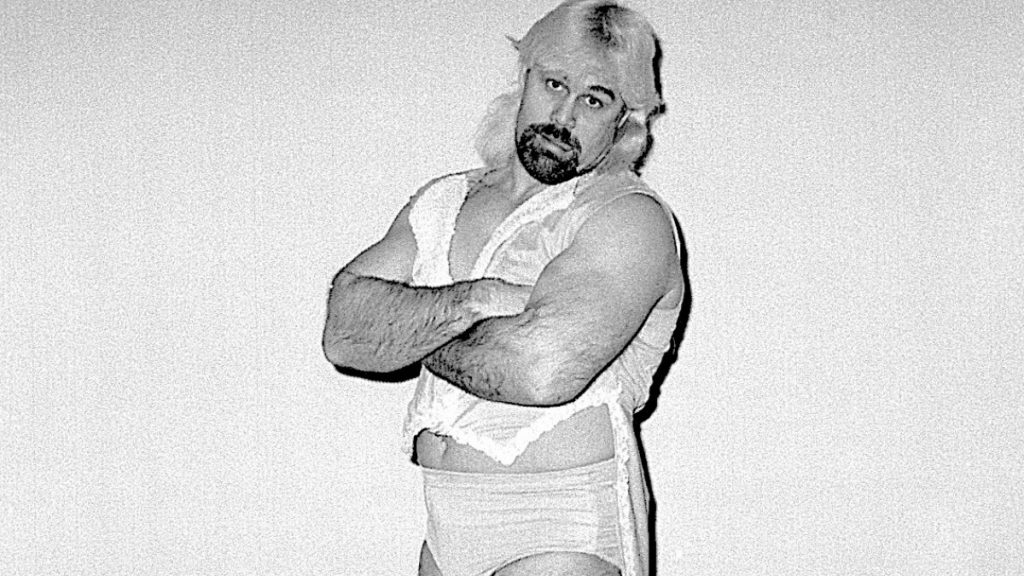

Rip Rogers. Courtesy of the Wrestilng Revue Archives

Working at around 220 pounds on a 5-foot-11 frame, Rogers was never going to be a regular main eventer in the days of the bodybuilders, but he made up for it with talent. Rogers had the ability to make others look good, using the “pretty boy” gimmick that became his trademark.

Guys “can get over with me because I’ve got no ego. You can beat me, I don’t give a rat’s ass. I know how to keep my heat,” he said. “It didn’t matter how big I was, and I didn’t need a belt either. When I was booker, I’d never be champion. I didn’t need a belt. The other guys needed a belt, I just didn’t need it. When a guy’s laying on his back, it don’t matter how big they are.”

He contrasted two big mean in Bruiser Brody and Ox Baker, both of whom he worked programs with. “I drew more money with Ox Baker, and Ox Baker didn’t touch me. Bruiser Brody would want to beat you up, and he’d look like a dick because he’s a prick in the ring. He’s so big, and he couldn’t beat me, what does that make him look like? Makes him look stupid.”

The understanding that Rogers has for the business, as well as his talent, mean that he had the respect of some of his peers.

“Rip Rogers is just one of the best all-around, down-to-earth guys I’ve ever encountered. He is very dedicated to the wrestling business and excellent at what he does. I will always love that man as a friend and a great partner,” wrote “Playboy” Buddy Rose on his website.

Bob Roop concurred. “I liked Rip. He’s got a good personality. He always worked hard. He was devil may care.”

Growing up in Seymour, Indiana, Mark Sciarra had a dream; he went as far as writing in the Seymour High School newspaper, The Owl, that he was going to be a professional wrestler. After graduating high school in 1972, Sciarra went to Indiana Central and played football. He became a teacher at Union City, and was also the football coach, finishing with a 9-1 record that season.

But teaching didn’t work out the way he wanted, and Sciarra left after one year, becoming the manager of Hofmeister’s Gym in Indianapolis. It was there, in 1978, that he met “Handsome” Jimmy Valiant, who convinced him to try pro wrestling.

A weekend warrior was created, wrestling when he could for Dick the Bruiser’s Indianapolis-based WWA, and The Sheik’s Detroit promotion.

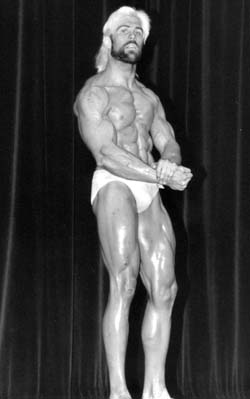

In action. Courtesy of the Wrestling Revue Archives

His big break came would eventually come in International Championship Wrestling, a renegade promotion run by the Poffo family — Angelo and Judy Poffo, and their sons Randy (Savage) and Lanny. But not before he worked for the Poffos out east in the Canadian Maritimes, where the family had a partnership with Emile Dupre in the summer promotion.

“Paul Christy said that the Poffos were looking for somebody to go to the Maritimes to work for Emile Dupre,” recalled Rogers, who was living in Indianapolis. He called Randy Savage, and went out east. The four-month stint in 1978 was mostly forgettable, said Rogers, who worked as Hercules Simard. He’d return to the Maritimes for three more summer tours — 1988, 1990 and 1997. In the 10 years between tours, he’d become a very polished worker, someone that Dupre sought out, not realizing he’d worked for him before.

“I was going to Japan, then Emile called me again at the hotel in Calgary, because Leo Burke wanted to work with me every day out there in the Maritimes. ‘Emile,’ I said, ‘How you doing?’ and started talking to him,” recounted Rogers with a laugh. “I said, ‘Emile, I worked for you.’ He said, ‘What?’ I said, ‘I worked for you as Hercules Simard in 1978.’ He said, ‘You did? My Gosh.’ I said, ‘Boy, I was a shit worker then.’ He said, ‘You sure got a whole lot better.'”

Rogers credits Randy Savage, who is one year his senior, for most of the education. “Randy Savage was so far ahead of everybody, so far ahead of everybody. He used to carry me in the Maritimes for full 30-minute matches, and I didn’t know how to tie my boots.”

Savage also got Rogers into better shape. “He pushed me into bodybuilding. I’d been training my whole life, and then he got into this competition … it was a thing where we were in our twenties, and we both had testosterone in us. He’d say shit, and I didn’t like him. I’d say shit and we’d get on each other’s nerves.”

After the first tour of the Maritimes, Rogers went to Nashville for Nick Gulas as The Disco Kid, and working as a tag team with Randy Savage. Then the Poffos got him booked through Frankie Cain, who was running opposition to Bill Watts in Mississippi in 1978; “Frankie Cain changed my name to Rip Rogers, because that’s the name that Eddie Graham used in Texas in 1955 to counteract Buddy Rogers, because he thought that I reminded him of him.”

In March 1979, Rogers participated in the initial ICW tapings. “We made 10 tapes for Channel 41 in Louisville. We made these tapes and put them in the can.” It would be a while before the promotion actually got off the ground.

In the meantime, Rogers went to Portland through Lanny Poffo, who was working there as Lanny Holiday. “I got to go out there and be Buddy Rose’s tag team partner. I worked with Rick Martel and the Bushwackers, Ron Starr, Adrian Adonis, Ed Wiskoski, Dutch Savage, ‘Tough’ Tony Borne. One of Matt Borne’s first matches out there, he busted me open. I just got to have a lot of fun out there.”

Kerry Brown and Rip Rogers in Stampede Wrestling Photo by Bob Leonard

Buddy Rose came up with Rogers’ “Hustler” nickname. “Rip needed a gimmick name and we came up with one in less than 5 minutes. It was absolutely perfect for him. You just never know when inspiration will hit,” said Rose.

“We were at Sandy Barr’s Flea Market at the Portland Sports Arena, just looking at things,” Rogers explained. “Buddy pointed out a pile of dirty magazines then said, ‘See, there’s Playboy, Penthouse, Hustler. So if I’m the Playboy, then you’re the Hustler.’ The name stuck.”

Besides Rose, Rogers also gives props to Roddy Piper for giving his confidence. “I was just green as grass in the ring, and Roddy would say, ‘Call it.’ Adrian Adonis would be sort of a prick, right? He’d want to call everything. Piper would get on his ass, ‘The kid’s got to learn, let him call it.’ Him and Ron Starr wanted to eat me up all the time. I wasn’t smart enough, and they’d just eat us up, eat us up, eat us up.”

The next four years — 1979 to 1983 — were spent primarily working for the Poffo ICW promotion, based out of Lexington, Kentucky.

It was an incredible learning experience, he said. “I basically learned this business from his family. I was in promotion, running towns with them, handling the sponsors. I got to ride in the cars with [Angelo], who rode in a car with Buddy Rogers. He’d tell me these stories. I got to ride in a car with Bob Orton Jr., Ronnie Garvin, Bob Roop, Boris Malenko. I’m just a rookie and these guys have all these years of experience. They’re telling me everything I’m doing stupid and doing wrong. I’m just sucking up knowledge, and we’re working 360 days of the year. … I was just fortunate to work with these guys that we just so good.”

Today, he can look back and realize how lucky he was. “Until you get away from it, like many things, you don’t realize the education that you’ve got, the training you got; I was taught about promotion, about television, about how to run shows, how to take no shit from the boys, how to run a balanced card, how to keep everybody in their place as far as overstepping your bounds, how to chase a title, how to give them a finish when it needed to be done, how to lay down when you needed to be lay down, how to do a strong finish when it needs to be — all this shit that everybody, they either don’t care or they don’t know about, but it was just talked about like common knowledge then.”

Eventually, when partners Roop and Malenko left, Rogers was offered a chance to buy into the promotion as a business partner. “I had 10 [points], Garvin had 10, the Poffos all had 20,” he explained.

His ex-wife Brenda Britton was his manager in ICW for a time, and he formed successful tag teams with Gary Royal (they were the Convertible Blonds), with Ricky Starr, and Pez Whatley.

Rip Rogers and Brenda Britton. Courtesy of the Wrestling Revue Archives

After ICW closed its doors, Ronnie Garvin booked him for the Fullers’ Continental promotion. It was another chance to learn. “I went in to work for Ron Fuller, and started out as a junior heavyweight. He said, ‘I don’t know what to do with you.’ He was honest,” recalled Rogers. “He said, ‘You’re getting more reaction than anybody. I’m either going to have to keep you completely off TV or give you a push.’ He kept me off TV for six weeks and it didn’t matter. Then, all of a sudden, he did an angle where I weighed in as a junior heavyweight, but I was too heavy. They started calling me ‘Fatso.’ I weighed 212 pounds, and I played up the Fatso act. Pretty soon, I’m working an eight-week program with Austin Idol. He did it as a one-week thing to see how it goes, and it went eight weeks. The two best houses were Flair and Andre, $4,232, and that was with a $5 ticket price … Me and Idol did over five grand, yet we were locals. So you just don’t know. Everybody’s got to get the chance to run with the ball. Some people succeed, other people don’t; there are other factors.”

Rogers then really hit the road, working Mid-South for Bill Watts, then Atlanta, Florida and Memphis for the Jarretts. Back with the Fullers, he worked a lengthy feud with Adrian Street. “You had to go with the flow with Adrian,” Rogers explained. “Me and Adrian never talked over a match. All that mattered was the finish, and what we were coming back with. The rest was ad lib out there.”

In Kansas City, Rogers helped with the booking. Internationally, he went to South Africa, Stampede Wrestling in Calgary, Japan, Korea, Trinidad, Puerto Rico …

Current WWE star William Regal credits Rogers for landing him his big break in North America in WCW, while they were both competing in Germany. “Rip did me a big favour while we were in Germany: he asked me if I’d heard anything from WCW. I hadn’t. I’d been sending them postcards from wherever I was working, saying who I was, how I’d tried out for them and letting them know where I was working now,” Regal wrote in his autobiography, Walking a Golden Mile. “But Rip had news. A guy called Bill Watts had taken over at WCW. Rip had worked for Bill and knew what he liked to hear. So he said he’d dictate a letter I could send to Bill which would get on his right side.”

The Convertible Blonds: Ric Starr, Rip Rogers and Gary Royal

By 1990, the territories had pretty well died off, and Rogers went to work for World Championship Wrestling, but with the freedom to work elsewhere. “I’d work every show for WCW that I wanted to, because Ole [Anderson] was the booker. If I wanted to go on tour, I’d go on tour. But he’d book me for every television, whether I wanted to work or not.” Rogers was also allowed to bring other young, up-and-coming wrestlers to the tapings to be used as enhancement talent. He was on his way to becoming a trainer, someone that newcomers look up to just like he used to look up to Angelo Poffo or The Great Malenko.

“Rip did his share of enhancement work, too, but only because he was so good at getting other wrestlers over,” said Rose. “The promoters knew he could help them create superstars through his matches, and he was paid accordingly for his skill and experience. It takes a LOT of talent to be a successful enhancement worker.”

The upstart Global Wrestling Federation lured Rogers in, and he was put in a faction known as The Cartel, with Max Andrews as the manager, and partners Scotty Anthony, Makhan Singh (Mike Shaw) and Cactus Jack (Mick Foley).

When the GWF died off, WCW hired him to run smaller “developmental” towns, where the big stars wouldn’t usually appear. “I’d work the first match, get paid; be the promoter, get paid; be the timekeeper, get paid; get the ring jackets, get paid. And I had a per diem, because I was the promoter,” said Rogers. “[WCW boss Eric] Bischoff got mad because these small towns were outdrawing the bigger towns. Their perception was that they’d rather lose a quarter of a million dollars and run the Astrodome than to make money. That was Bischoff’s famous saying.”

For the former teacher, all the lessons learned through the years paid off with his position as a trainer for Ohio Valley Wrestling, a World Wrestling Entertainment associated developmental territory. For a long time, Rogers taught the class that was above the bigger class, and talked about having a hand in the training of recent WWE stars Johnny Jeter, Nick “Eugene” Dinsmore, the Basham brothers, and Rob Conway. He also took to the ring there on shows, teaming with Dave the Rave for two OVW tag title reigns, and once with Jason Lee, when they were the Suicide Blondes. He also held the OVW title three times.

These days, OVW is a part-time gig for him, taking up a dozen hours or so a week. He saved his money — “Getting money out of him is like running a Starbucks in Death Valley in the middle of summer,” said Rose — and works a regular job, raising a young family.

He doesn’t have a problem summing up the secret of professional wrestling either. “It’s all the same. You either know how to work or you don’t. … It’s give and take, heel and babyface.”

RELATED LINKS