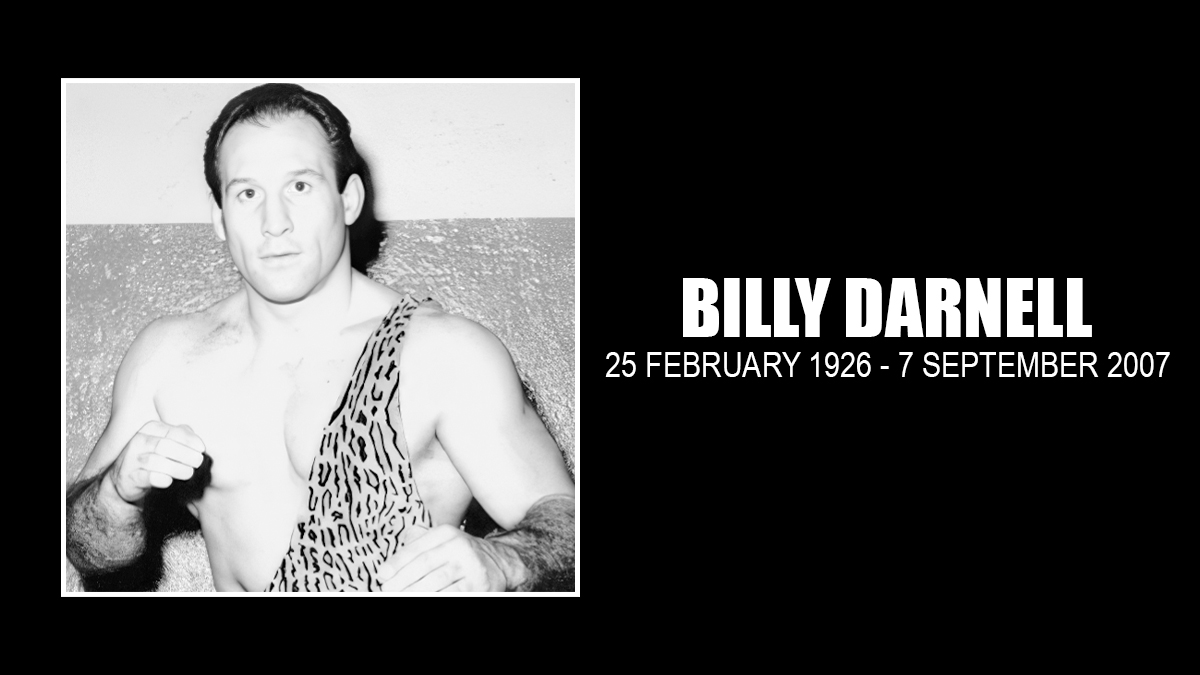

In basketball, Bill Russell had Wilt Chamberlain. In tennis, Pete Sampras had Andre Agassi. And in wrestling, Buddy Rogers, one of the greatest attractions in the history of the sport, had Billy Darnell.

“I was just a kid and didn’t understand what I was watching, but I guess it was the smoothness, the flow that made it special … the way they took the crowd up and down,” veteran wrestler and trainer Les Thatcher reflected. “I told Billy Darnell in Mobile [Ala.] a couple of years ago that their matches are one of the reasons I was in the business.”

That link to a vital component of wrestling history passed Sept. 7, 2007, when Darnell, one of the premier matinee idols of 1950s-era wrestling, died at 81 at his home in Maple Shade, N.J. Though he had not been in the ring in 45 years, the memories of his work with Rogers, a former world champion in the National Wrestling Alliance and the World Wide Wrestling Federation, stirred many contemporaries.

“Both those guys could work a good lick,” longtime star Red Bastien said.

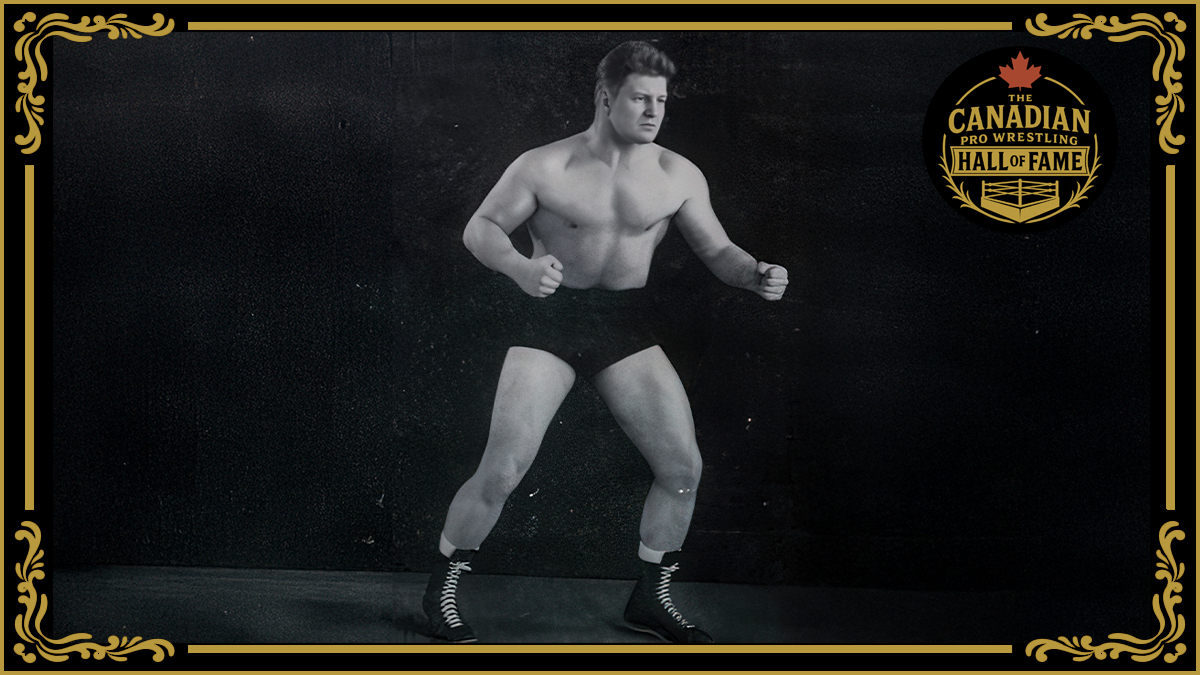

Born February 25, 1926 in Camden, N.J., Darnell got into wrestling more or less by accident. He was a lifeguard at the beach near Wildwood, N.J., where he’d roughhouse with other lifeguards. A passing promoter saw him and invited him to fill a void left by wrestlers who were departing for service in World War II. He was 16.

“I didn’t know that much about it, but I worked out, was pretty athletic and it was a way to make a couple bucks,” he said in an interview with SLAM! Wrestling in 2006. Darnell started working a little on the East Coast.

His first acquaintance with Rogers, wrestling under his real name of Herman “Dutch” Rohde came in February 1944 when the two teamed together in Philadelphia. The two teamed together in the Baltimore-Washington market that fall until Darnell’s career took a military-related detour, as he joined the U.S. Army in December 1944.

Coming out of the service, Darnell’s buff physique and crowd-pleasing style got him booked in Texas as Billy Rogers, brother of Rohde, who had started his transition to the “Nature Boy” persona. According to Darnell, promoter Jack Pfefer, who handled Rogers’ bookings at the time, was a key player in the evolution of his career.

“Buddy had wrestled for [promoter] Morris Sigel down in Texas. I don’t know whether it was Buddy or Jack Pfefer; somebody asked me to go down and wrestle as Billy Rogers. So I went down there for a few months,” he said.

That was a stepping-stone to bigger and better things. Pfefer got both of his charges booked in the lucrative California market, just as televised wrestling was taking off. Rogers got a sequined cape and an attendant, while the colorful Pfefer introduced Darnell to what would be his signature leopard-skin apparel.

“[Rogers] went in there first and then I came in,” Darnell recalled. “He had the slave girl, Helen Hild, the girl wrestler. Then I came in there. I became junior heavyweight champion and Buddy was a heavyweight; he was a little bigger.”

Working frequently with Rogers, Darnell became a star on shows televised from Hollywood Legion Stadium. “That’s where we really hit it big, when we wrestled a few shots out there. But after that, everybody wanted that match.”

Though Rogers and Darnell knew each other like the back of their hands — wrestling historians have recorded more than 200 matches between them in the ’40s and ’50s — miscues still occurred. In one match, a botched piledriver crushed discs in Darnell’s neck, though he was wrestling again before long.

“I wore a collar for about a year. I used to hang myself, I had a chinning bar I carried with me everywhere. I put the thing on my neck and hung myself with pulleys,” he said. On the other end, he accidentally knocked out a couple of Rogers’ teeth; his pal had to have dental implants, he said.

Darnell also is remembered for his excellent tag team with Bill Melby, a pairing that won the Chicago-based version of the World tag title in 1953 and defended the belts around the country. “We were on TV in Chicago, New York, Columbus, St. Louis, so everybody had a chance to see us. Sometimes I’d clear $1,000 in a week,” Darnell said. Melby said that it was promoter Jim Barnett that paired them up. “He had some good moves and worked well together. I enjoyed Billy Darnell a lot. A real, real nice guy,” recalled Melby. “We made a little money, that’s the main thing. That’s what we were all after.”

After a year of headlining, the pair decided to call it quits in 1954. “We were traveling in Bill’s coupe on roads going 85 mph so we could get to town and get some sleep, get to a gym and work out,” Darnell said. “That wears you down.”

The babyface star also moved into the front office for a while. Darnell booked for Sam Muchnick in St. Louis for several months and also helped to run the Indiana promotion for a time.

“Sam couldn’t fill three rows, so I called George Bollas and some others and we started having sellouts. In Evansville, Ind., I booked Bob McCune with Buddy and we had to go from the 3,000-seat arena to the 10,000-seat arena.”

Darnell was a pilot, as well, using his GI Bill from World War II to attend aviation school. “I was wrestling, promoting, and I ran a nightclub-bar until 1985. I owned my own plane and flew to all my matches,” the ultra-busy Darnell said upon being honored by the Cauliflower Alley Club during its 2004 reunion in Las Vegas.

Always interested in a career after wrestling, Darnell enrolled in chiropractic school in Glendale, Calif., and finished up at a school in Indiana. He retired from wrestling in 1961, though he continued to wrestle a few bouts on the East Coast near his New Jersey home through 1962. He established a successful chiropractic practice there, treating patients even long after retirement age. Darnell moved for a while to Florida, where he rekindled his friendship with Rogers, before heading back to New Jersey.

“Buddy was an all-around great athlete. He could do it all. I thought he was top of the line,” Darnell said of his old pal.

Darnell was a regular attendee at Cauliflower Alley Club reunions and earlier this year received the Senator Hugh Farley Award from the Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame in Amsterdam, N.Y. An avid dancer, he went dancing every weekend until he died. His wife Betty preceded him in death and he is survived by a daughter, two granddaughters, a sister, nieces and nephews.

A graveside service will be held at 11 a.m., Sept. 12, at Locustwood Cemetery in Cherry Hill, N.J.