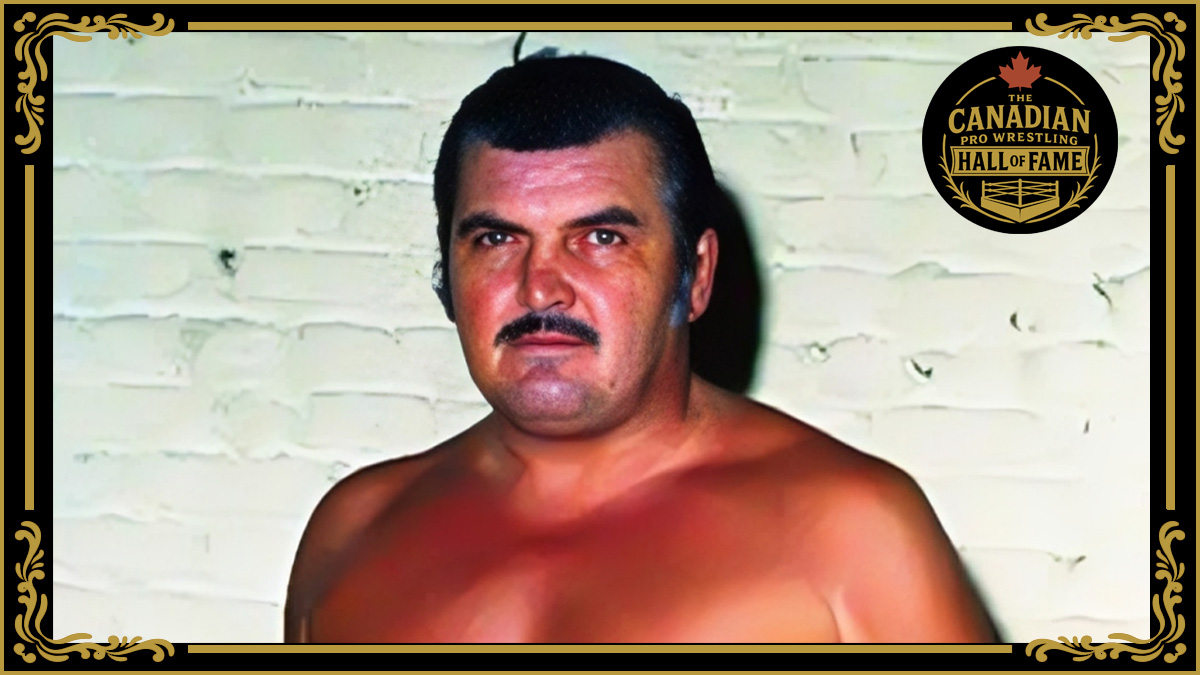

Not too many Hungarian- Canadians become icons in Texas wrestling history, but Bronko Lubich, who died Saturday at the age of 81, did. His in-ring career done, Lubich became a high-profile referee for World Class Championship Wrestling, and stayed in the spotlight until his retirement in 1990.

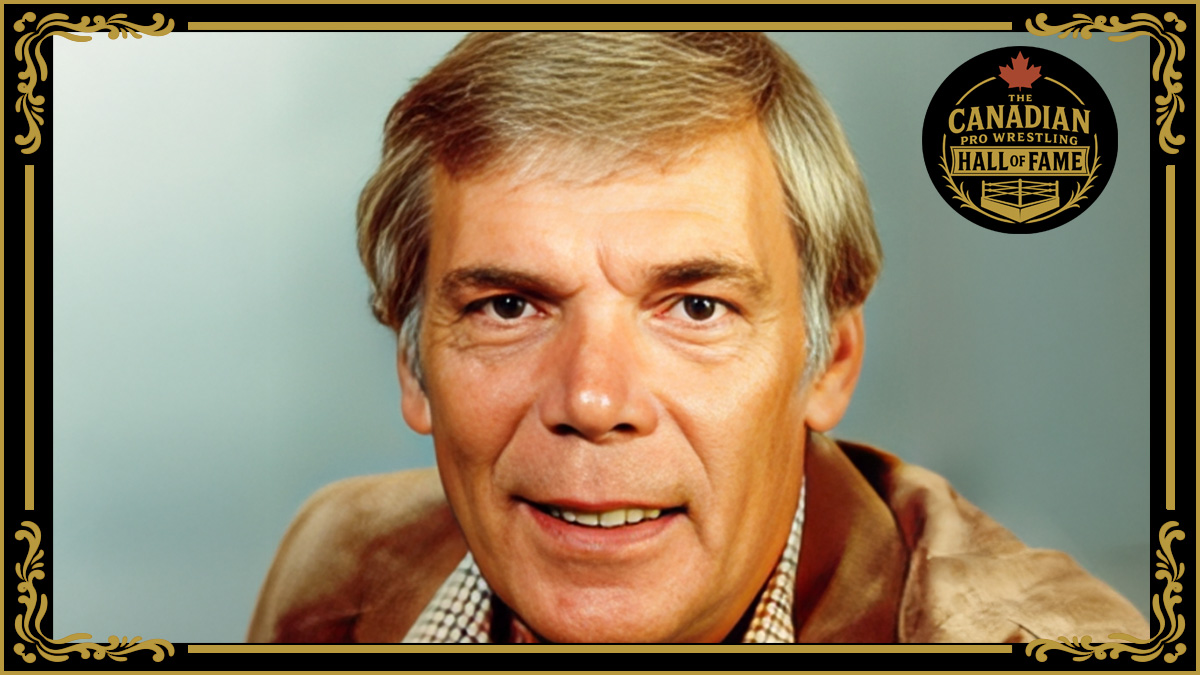

As a referee, he certainly wasn’t the fastest in the game. But he did command respect, said World Class announcer Bill Mercer. And with the program one of the first to take advantage of the reach of cable television, lots and lots of people got to know Lubich as a referee rather than a wrestler.

“He was one of those calming people. He always had that aura of a guy that we could trust, even thought he’d be fooled by whatever was going on. I think that all the fans thought they could trust him,” said Mercer. “I think he was a stable of the wrestling people. The fans respected him. I think everybody respected Bronco.”

For example, Lubich was the referee for the all-important NWA World title match where Jack Brisco defeated Harley Race in Houston in 1973.

In an interview with Scott Teal, Scott Casey talked about Lubich’s command of the situation in the ring. “He was a great referee. If he saw something wrong, he’d tell you. He’d correct you right in midstream,” Casey said.

No less than “Stone Cold” Steve Austin praised Lubich and Skandor Akbar for taking him under their wing in Texas, and helping him learn.

“We’d be together in one of their cars, and they’d be up front smoking big, smelly cigars and I’d be in the backseat asking them questions and soaking up everything they were telling me. That was a college degree in the old-school ways of doing things. I love those guys,” Austin wrote in his autobiography.

“Sometimes they’d tell me old wrestling stories. I’d always enjoy hearing those. I didn’t have any money then, and they wouldn’t charge me for transportation. I’d just sit in the back and ask them questions. Those guys were cool. They knew I was genuinely interested in learning, and they both took me under their wings.

“Both Akbar and Bronk were excellent storytellers. When one of them told a story, the way they laughed made me want to laugh too. It was a real good time in my life. Those guys and their wealth of knowledge about ring psychology were tremendous influences on me throughout my whole career. They also furthered my respect for the wrestling business.”

He was born Bronko Sandor Lupsity on December 25, 1925 in Battonya, Hungary. The family moved to Montreal in December 1937, following their father, who had moved over earlier and earned enough money to bring his wife and two sons over by boat.

Growing up in Montreal, Lubich and his buddies got in regular trouble until it was suggested they go to the local YMCA to burn off their energy. There, they met Montreal pro wrestlers like Harry Madison and Mike DiMitre, who encouraged him to try pro wrestling after mastering some amateur skills.

Beginning as a pro in 1948, at 6-foot, 175 pounds, Lubich wasn’t a monstrous specimen by any means, but in that era, it was possible to head to lighterweight territories to find work.

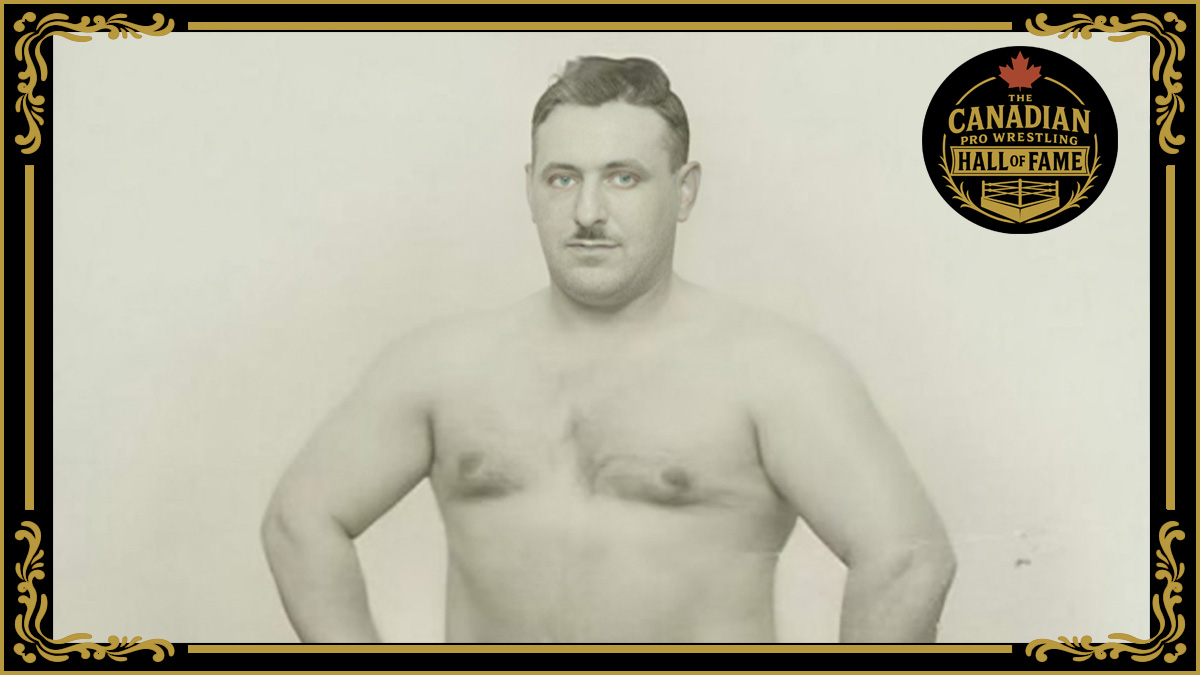

His first big break came as a valet to Angelo Poffo — a great learning experience. “We made a lot of money together,” said Poffo. “He did what I told him to do … a lot of people tell the promoter, ‘Give me six weeks to get over.’ And I said, ‘Give me one match to get over.’ I go out there to wrestle, and the guy was dumping me all over the place like Wilbur Snyder, who was a great worker and a nice guy. Then at the end of the match, Bronco would pull his leg and I’d beat him and I created a riot. It’s that simple.”

As a wrestler, most fans would know Lubich best from his tag teams.

The best known pairing was Lubich and Aldo Bogni, who was two years old, and predeceased him partner in 1997. When manager “Colonel” Homer O’Dell, or later George “Two Ton” Harris, were added to the team, it produced pure hatred from the fans. “The thing about Aldo and Bronco was their heel foreign gimmick (Buenos Aires, Argentina, and Belgrade, Yugoslavia) that was made that much more effective by Homer in their corner. Real heat magnets,” recalled Charleston, S.C. reporter Mike Mooneyham, who grew up watching them. O’Dell even carried a revolver and would shoot it behind the arena to scare off fans who might pose a problem.

“He met up with Aldo in Charlotte, North Carolina. That was at the recommendation of the promoter at the time, Jim Crockett,” explained Kathy Lupsity, Lubich’s oldest daughter. It was Crockett who hooked them up with O’Dell (who was later, mysteriously, promoted to “General”). O’Dell “sold” Bogni and Lubich to Harris. The new manager added an extra dimension to the team, and allowed for countless six-man tags where the faces could get their licks in on Harris.

One of their regular opponents in Charlotte were the Flying Scotts. “They were good wrestlers and they worked their butts off,” remembered George Scott. They would team through the 1960s into the early ’70s in the Carolinas, Stampede (where Bogni was Count Alexis Bruga) and Florida, and feuded with George Becker and Johnny Weaver, Rip Hawk and Swede Hanson, the Andersons and Mr. Wrestling & Sam Steamboat.

Chris Markoff was another partner, and Lubich was working with him when photographer Geoff Winningham caught up with them in Houston at the matches for a photoshoot for Life magazine that would lead to the book, Friday Night in the Coliseum (Allison Press, 1971).

Lubich is quoted in the book, explaining a little what it is like to be a pro wrestler:

“People are right when they say this is a violent sport. You must have violence in you to do it. No matter how much you want the money. People say I am a gentle person when they meet me. Naturally I do not stand around and growl at people on the streets. But I am basically very easily aroused. You just learn to control it. You have to live with people, and you can’t go through life pushing them around. I concentrate on being a gentleman. But when I am in the ring it is a different story. I am out there to beat my opponent. And he is trying to beat me. Then it comes down to dollars and cents.”

The dollars and cents mention is appropriate.

His wife, Ella, with whom he had three children, was a penny pincher, said their daughter Kathy. But Lubich learned to save his money well. She credits Poffo, who once used the nickname “The Miser.”

“When they’d go on to the next city, they’d like to get there really early, to relax, read the paper, eat … sometimes they’d catch a movie. But the biggest thing that he and Angelo used to do is to go down to the Merrill Lynch office, any close Merrill Lynch office, to talk to the guys about investment,” said Kathy Lubich. “He and Ang started really investing in different stocks. They’d find the closest Merrill Lynch office and check and see how their stock was doing. Daddy knew there was no retirement fund in wrestling. It was totally up to you to make your own investments. So he and Angelo Poffo started a long, long time ago, investing in stocks, bonds and all that kind of stuff.”

Other investment info came from Jim Crockett Sr.

“These guys used to come into the dressing room and talk about what a great house it was the night before, how much money they made and they were going out that night. Basically blowing it, staying at these expensive hotels and eating at these expensive restaurants,” continued Kathy. “Daddy and Ang used to sleep in the car sometimes between cities. Daddy would tell them, ‘Geez whiz, you’re doing so good and making some good money now. Do you have a savings account? Are you investing it?’ The guys were like, ‘No Bronk, get out of here! I’m just here for a good time, Bronk!’ Dad would say, ‘This isn’t going to last forever. You need to take some of that and put it away, do something with it.’ He got a reputation. After a while a lot of the guys started coming to him saying, ‘So, Bronk, what stock do you think I should invest in?'”

Mercer concurred. “Behind-the-scenes, he was a guy that anybody could go to and ask questions and get answers to, and give you the run down on what was going on. … He was one that had a little more common sense about him.”

The reward for Lubich came at Christmas time, when the greeting cards would express thanks. “There would be notes inside, ‘Bronk, I can’t thank you enough for encouraging me to invest. Thank God I did. Now I do have something to fall back on,” said Kathy.

The last years for the Lubichs — Texas residents since 1971 — were tough. Ella was diagnosed with cancer in 1997; they had planned to travel using the money they had saved. “Everything changed. She got sick, he got sick, she got sick. At least the deal was they each took turns, they weren’t sick at the same time,” said Kathy. Ella died in September 2004.

Bronko battled prostate cancer and suffered numerous strokes. He had a very difficult time speaking. Lubich died on Saturday, August 11, 2007, in Dallas, Texas.

He is survived by his three daughters, Kathy, Maria and Melonie.