When people talk about wrestling movies, I Like To Hurt People is usually mentioned near the top. The mix of documentary and hokey acting has built a cult following in and out of the wrestling world, but it is admired by longtime wrestling fans.

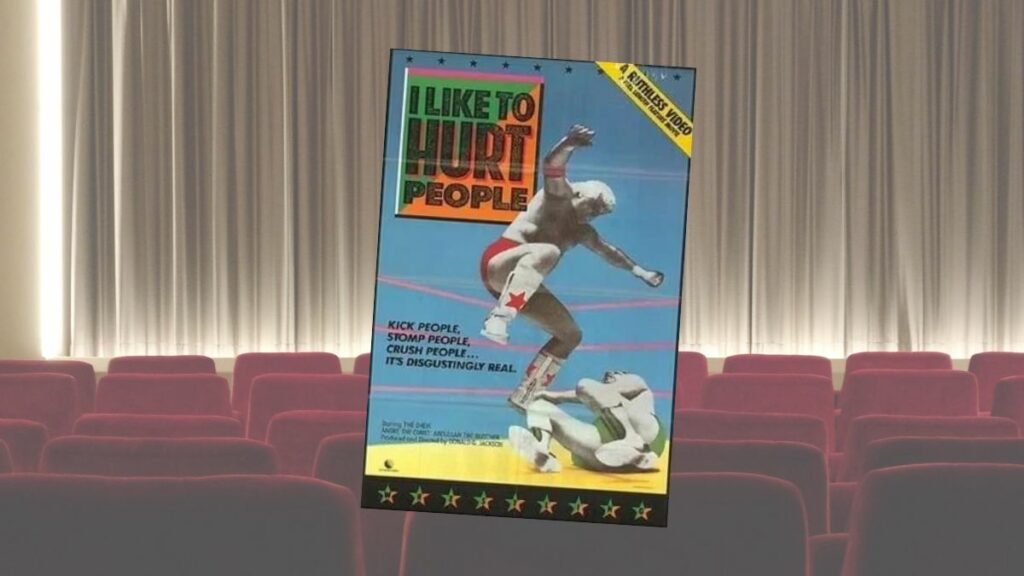

The DVD of I Like to Hurt People

Bryan Greenberg, who worked as Producer and Director of Photography, remembers the making of the film like it was yesterday.

The original idea was to film a horror movie called Ringside in Hell. When the horror aspect was dropped, it would become Ringside. Stories were built around real life wrestling matches. Greenberg has obtained most of the original footage, shot in the mid-’70s, and hopes within the next few years to release the movie close to the original concept.

“When we realized we couldn’t film the wrestlers for days and weeks at a time, the idea went from a movie to more of a documentary,” Greenberg told SLAM! Wrestling. “Hair colors would change, new scars would appear, and so it was easier to shoot it as a documentary.”

Funding was lacking and the movie was put on the backburner. It was to Greenberg’s surprise when the movie was released on video and laserdisc in 1985 under the title I Like To Hurt People.

Donald G. Jackson, director and producer of the film, had struck a deal with New World Video to sell movies he produced for New World’s new laserdisc line. New World funded Jackson to shoot additional footage in 1984, which is when “Stop the Sheik” footage was shot (for those who have seen the movie, no explanation is needed).

So within the documentary interlaced a plotline about stopping The Sheik, a legendary villain featured throughout the movie. New World believed a movie would sell better than a documentary.

Crew prepare for a scene with Dick the Bruiser before his match with The Sheik. From left to right: Bryan Greenberg (Cinematographer), Don Jackson (Producer), Dick the Bruiser, Bob Finnegan (Associate Producer) and Dennis Stotak (Sound Recordist). Photo courtesy of Bryan Greenberg.

Greenberg was brought into the project while working as a cameraman locally in Detroit. Robert Flannaghan, who co-produced the movie, introduced the crew to The Sheik, who’s real name was Ed Farhat, the local promoter in the Detroit territory.

“He was very open to the idea,” Greenberg recalled. “He just wanted to make sure nothing about the insides of the business was exposed. He gave us free reign, and helped organize the wrestlers who were in the movie to work with us.”

Footage of Andre the Giant lifting a man onto the top of a car was shot the day before the matches, Greenberg recalled. “The Sheik would tell the wrestler to come with us, and we would direct them on what to do. Andre the Giant was still new to the U.S. (he was born in France) and had trouble speaking English, but was extremely nice to work with.”

Greenberg could not recall the exact amount, but knew it took numerous takes for Andre to say the line, “Are you talking to Andre?”

In an interview with Trash Times Magazine (reprinted here) before his passing in 2003, Jackson talked about the movie. “Hulk Hogan and Andre the Giant were both Superstar wrestlers and you just couldn’t touch them. They were both under very strict contacts — every time they were photographed or filmed, those images had to be approved by their managers and the wrestling federation. What I loved about The Sheik is that though he was a well known wrestler, he was his own man. I went up to him at a match one day, told him what I wanted to do. And, he was the nicest guy. He gave me full access. He also introduced me to many of the other wrestlers, who allowed me to film them, as well.”

Although conceived as a documentary, a lot of movie aspects were visible in the original footage. The camera was inside the ring after matches, which was unheard of at the time in wrestling. Insert shots of wrestlers entering the ring or close-ups of referees would be shot hours before the matches took place inside an empty arena.

A scene shot with female wrestler Heather Feather in her first match with a male opponent was shot with a camera dolly circling the ring, something that probably has never been reproduced in wrestling still to this day. “Heather Feather tells a story in the film about wrestling a bear, but a regret I have is that we did not shoot that match,” he said.

Farhat would keep the crew up to date on what matches were taking place each week, and the crew would decide what to film. Footage would be shot not only in Detroit but also Indianapolis, Toledo and Flint, as Greenberg recalled.

Was there anyone who was opposed to the film? “No one I can recall,” Greenberg said. “But I remember Bobo Brazil mentioned he was ‘signing his life away’ when signing his release for the film.”

Greenberg is still obtaining the additional footage shot for the film, but hopes to make something close to the original concept of the film in the future. “Pretty much people stayed in character when the cameras were on, but there is footage of guys drinking, laughing and things shot outside the ring I hope to release.”

One moment that Greenberg remembers was what happened after a scene featuring Eddie “The Brain” Creatchman and Abdullah Farouk (Ernie Roth, later The Grand Wizard). “The two were yelling at each other, the director called for a cut, and the two started laughing loudly. It’s one scene I hope I can find and add back into the film.”

Sonya Friedman

Many of the film’s crew have gone on to bigger and better things. Dennis Skotak, who was a camera operated on the movie, would go on to win a Special Effects Oscar from his work on Abyss (1989). He would also work on movies such as Terminator 2, Titanic and Aliens. Sonya Friedman, who appears on camera speaking about the psychological effects of wrestling, would go onto be a best selling author and have her on show on CNN in the late 1980s named Sonya Live.

Friedman helped finance the film but never received any compensation in return when the film was released years later. A request for an interview with Friedman was turned down.

Bryan Greenberg would have his own success in California during the birth of music videos in the early 1980s working on videos for Michael Jackson, Prince and Billy Joel. He still makes a career today as a cinematographer.

When Donald G. Jackson passed away in 2003, Greenberg acquired the rights to I Like to Hurt People, and has been able to obtain much, but not all, of the original footage.

“It’s a pet project I hope to finish soon,” Greenberg spoke about re-cutting the movie. “It is always good to know people when people mention and like the film.

RELATED LINK

New documentary offers look into cult classic ‘I Like To Hurt People’