With the death today of Abe Coleman, aged 101, professional wrestling lost probably its last link to the likes of Jim Londos, Man Mountain Dean and other stars of the 1930s.

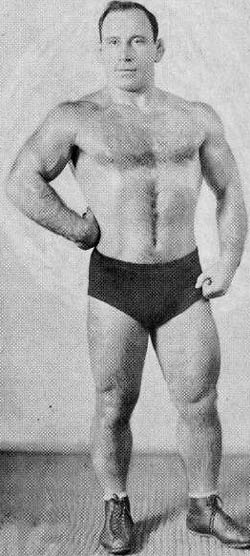

Coleman, who died in Queens, NY, was never a big national star on the wrestling circuit — he was a middle card fellow for most of his 2,000 matches, and was just 5-foot-3, on a solid 200-pound body.

“The squat New Yorker who was just a little over five feet tall and seemed at least that wide,” wrote Paul Boesch in his autobiography, Hey, Boy! Where’d You Get Them Ears? “Coleman liked to leap up and put his feet in his opponent’s face and did it frequently. But Abie never learned to use it with the explosive power needed to become a winning weapon.”

Abe Coleman

Not always being a headliner, however, does not mean Coleman didn’t live a fascinating life.

Born Abe Kelmer on September 20, 1905 in Poland, he emigrated to Canada in 1923. New York City would be his next home.

The story of his entry into the professional wrestling ranks was often repeated in newspaper stories as his age crept ever upward. It was 1929, and he was in a Brooklyn gym working out. Local promoter Rudy Miller approached him and said, “Hey kid, you want to make $25?” Kelmer agreed, and Abe Coleman was born.

But as with many tales, it is possible that the telling of it grew through the ages. There is an Abe Coleman on the March 19, 1928 show, which was the first card at the third incarnation of Madison Square Gardens, located on 8th Ave. Coleman went to a draw with George Deslonchamps.

Newspaper stories over the last few years also credit Coleman for bringing back the drop kick as a wrestling move after a tour of Australia. He would say that he had been inspired by seeing the kangaroos. However, it’s not mentioned in his publicity at the time.

(Another example of reporters not understanding wrestling — or perhaps economics. Coleman was said by a 1995 Newsday article to have made “about 10 percent of the profits, or $10,000 to $12,000 for a match” in the Depression. That would be a fabulous sum for a year during the Depression. Very few wrestlers could claim to make that amount today per match.)

The Ring magazine picked up on Coleman early in his career. In the “Current Wrestling Gossip” column by Tex Austin in the June 1932 issue, he’s given props. “Two short, squat, but fast and spectacular grapplers made very favorable impressions on New York fans in their debut. I refer to Abe Coleman, an energetic California Hebrew, and George Kotsonaros, the Greek actor-wrestler from Hollywood. Both will probably be seen in many thrilling matches in the East.”

The publicity didn’t stop. During the 1930s, there were few Jewish pro wrestlers, and Coleman was billed at times as the “Hebrew Hercules” and “The Jewish Tarzan.” He was also called “Little Hercules.”

Some other examples:

The Ring, January 1933: “Abe Coleman, chunky California Hebrew, gained for himself a large following by his masterful exhibitions in pinning Dick Daviscourt and Rudy Dusek after punishing matches.”

The Ring, June 1933: “Abe Coleman, the ‘Ape Man,’ is one of the most popular Jewish wrestlers that has ever been developed in this country. He is popular primarily because of his aggressiveness and the fact that he is so small. Abe weighs over 200 pounds but is only 5 feet, 6 inches in height.”

Source unknown: “Coleman, not a big fellow but exceedingly hard to hard to handle, combines cleverness with speed and science and a mental makeup which spares his opponent no punishment. He is master of about every hold known to wrestling and can invent one or two when needed. He knows how to apply them so that he can inflict the most possible torture of a foe.”

Coleman did get in the ring with some of the greats of the day. He faced Jim Londos, Man Mountain Dean, Ted Cox, George Zaharias, George Temple and the Dusek brothers. He is also credited with tipping off St. Louis promoter Tom Packs about Orville Brown being a future star (and future world champion).

“I beat ’em all,” Coleman told the Queens (NY) Chronicle-Central Edition before his 100th birthday. “Jim Londos was tough, but I was tougher.”

In 1939, Coleman married June Miller. “I was wrestling at Madison Square Garden in the spring of 1936. I was thrown out of the ring and landed right in her lap,” Coleman told Newsday in 1995. June died in 1987, and the couple had no children.

Coleman’s career would last until the early 1950s. In Wrestling Fan’s Book, put out in 1952, author Sid Feder wrote: “Called ‘The Little Giant’ because of his compact build (5-foot-4 and 220 pounds)… He has been wrestling over twenty years… In 1936, he and Man Mountain Dean drew 36,000 to their match; Coleman won… Now promotes as well as wrestles, working with Bill Johnston on his New York shows… Coleman’s widely-known kangaroo dropkick was the result of studying the animal’s antics during an Australian tour in 1931.”

Reno, Nevada, 1935

Besides promoting the occasional show in small New York City locations with partner Bill Johnston (son of the former promoter Jimmy Johnston), Coleman served as a wrestling referee.

The April 1959 issue of Boxing Illustrated / Wrestling News gives prominence to Coleman as the referee for a bout between Johnny Valentine and Bola Hawkawa in Washington, DC. “But before he could reach three, Valentine had Hawkawa’s lump upper body in an upright position again, slugging him over the head. Finally, in a fit of anger, Coleman grabbed a fistful of Valentine’s golden hair and jerked him off the lifeless form. Coleman shoved his first under Valentine’s nose, threatened to bash his face in as the angry mob egged him on. But the official restrained himself and did the only thing he could do. Reluctantly, he lifted Valentine’s pole-like arm, held it up for a fraction of a second, then tossed it aside as one does with an old shoe.”

Outside the ring, Coleman inspected license plates for the New York State Department of Motor Vehicles. He was honoured by his peers on September 30, 1995, when the Cauliflower Alley Club presented him with an award at a banquet in Elizabeth, NJ.

For the last few years, he was mostly confined to a wheelchair, living at the Meadow Park Rehabilitation and Health Care Center in Flushing, NY.

Previously, he lived in Forest Hills, NY. It was there, when he was in his 80s, that two teens attempted to mug him. As the story goes, Coleman subdued the aggressive youth for the police, with some stories saying it was with a vicious hold, and others that it was a couple of solid punches.

As Coleman would say in his later years, “Who else had a better life than me?”