It’s been 100 years, today, since Primo Carnera was born. His name may not be familiar to today’s fan, but it should be. His story is one of making good in a new world, and sadly, having it all taken away. SLAM! Wrestling is pleased to be able to share in the memory of the boxing and wrestling great with a classic reprint from SPORT magazine. Enjoy!

The story of Primo Carnera, the uncommon, outlandish giant of the 20th Century, will be a difficult one for future generations to believe. Even now, well over a decade since the most brutal episodes took place, a reporter delving into Primo’s past needs a strong stomach not to be sickened by the facts he uncovers–the filth, the greed, the depravity. This is not, in essence, a sport story, but the tale of a gargantuan, simple, and yes, courageous man who was preyed upon by all the known varieties of human lice.

Those in the fight game who have read Budd Schulberg’s best-seller, The Harder They Fall, recognize it as a thinly disguised novel of Carnera’s life. It etches a sharp and sordid picture of conditions in Cauliflower Alley in the ’30s. It throws a harsh light on the thugs who, through violence and skullduggery, made this helpless giant the heavyweight champion of the world. It shows how they then cheated, befouled, and degraded him, and left him at the last a battered, paralyzed wreck, friendless and without hope.

Everyone connected with the ring knows the shameful details. No one knows them better than Primo. “That book, yes, I have read it,” he said, nodding his huge head. “It is all true.” Then he spread his tremendous, ham-like hands. “But I wish he had come to me. I would tell him so much more.”

Carnera could. For, although the novel tells what happened to Carnera on the American scene, although it exposes the gangsters, gamblers, politicians, bankers, bums, fighters, trainers, and petty crooks who infected his career, it does not tell the complete story. It could not tell it completely, because the story has not yet ended. It is still being lived by Primo Carnera. And it will not end, as the novel did, on a note of despair. The story, in its entirety, is not only one of man’s inhumanity to man, but one that reveals the dignity of the human spirit, and shows the courage of a pitiful creature who refused to stay down.

Nobody in the fight game likes to talk about Carnera’s ring career. Even those who were in no way responsible for it give their information grudgingly. They say it would be best if it were forgotten. The only one who will talk about it honestly, completely, is Primo Carnera himself, the one man who has nothing to hide, the one man who has done nothing of which to be ashamed. Of the dozens of people, the decent and the dirty, who contributed to this document, none gave so much or so freely and fairly as Carnera. At times the simple dignity of his words gave you a choked-up feeling in the throat. His lack of bitterness, where bitterness should have been, created an anger in the listener. Primo Carnera told his story from the beginning. It is the only way it should be told. It is the only way the events which took place can be wholly understood, seen in their proper light against the confusing, chaotic, shifting background of treachery and rapaciousness. It is impossible to understand the forces that act upon a man, unless you know what he is, what conditioned him, how he became a thing that could be shaped, twisted, deceived, and tortured.

This is the story, from birth to now.

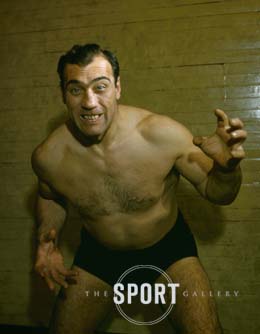

Primo Carnera © The SPORT Collection BUY THIS IMAGE

A birth is a most commonplace occurrence on this spinning earth, but it is always a thing of wonder. No man is a replica of another, nor will he ever be repeated. And so, perhaps, the wonder of birth is that into the world comes not only flesh and blood, another to take its place among the billions of shapes, but something new and different.

The child, born on October 26th, 1906, in the village of Sequals, in the North of Italy, weighed, at birth, 22 pounds. It was a most uncommon weight. But the mother, Giovanna, was not aware of that when she spoke to her husband, a stone-cutter named Sante Carnera, saying, “Since he is our first child, I shall call him Primo.” The word Primo in Italian means first, and the out-sized baby with the strange name was to be the first in the world in many ways–first and set apart from others, looked upon as a freak because of his tremendous proportions.

Carnera’s parents were of average weight and height, as were the two brothers who followed him into the world. The family was extremely poor. They lived in a hut-like structure in the foothills of the towering Alps. Sequals is a place of some 3,000 people and Primo’s father, Sante, eked out his existence in the manner of most men of the village, fashioning intricate mosaics in stone. The artistry of the craftsmen of Sequals, though poorly paid, earned them a reputation throughout Europe.

Primo and his brothers were taught stone-cutting almost as soon as they could stand. The brothers are still practicing that time-honored craft, one in Newark, New Jersey, the other in London. It would have been much happier for Primo if he had been allowed to stay at it. But the extraordinary man, the giant, has little chance of living an ordinary life. He is singled out, gawked at, prodded, exhibited, and forced along paths not of his choosing.

This pattern began early for the boy who was as large as a man, the mountainous Primo. His parents went to Germany to seek work, and the six-year-old boy was left with his grandmother. At eight, he was man-sized and apprenticed to a cabinet-maker to learn that trade. He became quite skillful at this work, attended school spasmodically, and proved to be of average intelligence.

“My childhood was miserable, very miserable.” It is an adjective Primo uses quite often. “We were always hungry. I worked very hard, extremely hard. At school I was not happy, I was too large to be accepted. Miserable. It was miserable.” He smiled. “I did not take part in the sports then. I was too large and clumsy. It was a bad time for me, this childhood time.”

This is the way Carnera spoke. Anyone who sits down with him for extended periods of time, who gets him over his initial shyness, is usually amazed by his manner of speech. Once you become accustomed to the booming, deep-toned voice, it is easy to follow what he is saying. His vocabulary is extensive, his choice of words intelligent.

During the time Primo was touring tank-towns in America, belting over set-ups, the sportswriters had a field day ridiculing this guileless, friendly foreign giant. Stories were circulated that he was as stupid as he was large. At the time, his unfamiliarity with the English language was offered as proof of his mental backwardness.

“What do you think of Hollywood?” a reporter was supposed to have asked him. “I knock him out in the second round,” Primo was reported as saying. It is possible that he did say it. An American, not familiar with the Italian language, might easily have made just as ridiculous an answer. It is a fact that Primo learned English very rapidly and, besides his native tongue, he also speaks French and Spanish fluently. The endless stories told to humiliate him did not go unnoticed, as many believed. They hurt, but Carnera took them without complaining, never losing his temper, always conducting himself with dignity.

Harry Markson, the press agent for the Twentieth Century Sporting Club, who sees more than the muscular surface of fighters, said: “Primo was a nice guy and a very sensitive guy. I remember,” he went on, “how he came in to Jimmy Johnston’s office one day. He took Murray Lewin the sportswriter aside and said, ‘Please, Mr. Lewin, call me anything you want, but do not call me Satchel Feet any more.’ He was very sweet about it and there was something pathetic about it, too.”

In talking about his childhood, Carnera did not try to play on sympathy, or exaggerate it. It would be hard to exaggerate. His parents, who had gone to Germany, were interned when World War I broke out, and were placed in a forced labor battalion.

They returned to Italy in 1918, when Primo was 11 years old. The war had had the usual devastating effect, and for a year the family was close to starvation. Carnera’s father finally set off for Cairo, where he had the promise of a job. When he began sending money back home, Primo decided it was time to get out on his own.

He was now 12 years old. He was around six feet tall. He looked like a man and people took him for a man. Carnera said that he had a miserable childhood. Actually, he had no childhood at all. At 12, almost penniless, he hoboed into France. For the next five years, the boy with the giant frame worked at everything he could to keep alive.

“I worked very hard,” he said, “so hard I was often weak and food was scarce. I did laborer’s work. I carry cement bags, lay bricks. I worked for a time at my father’s profession, the stone-cutting. I did all sorts of work. I could not go back. What for? There was nothing at home for me. The years were bad. I was an innocent,” he smiled. “How do you say it, an ingenuous child?”

At 17, the ingenuous child stood 6-foot-5, had a 50-inch chest, arms and legs like tree trunks. He weighed 250 pounds and was stalking through the streets of Paris hungry, with no job prospect in sight. In desperation, he appealed to the manager of a traveling circus. Here is a body, the boy said; do what you will with it, put it up for people to stare at, make jokes about, exhibit it for the world to see, do this to me, but food is necessary if I am to stay alive–and I wish to live.

The circus man did not need a sharp eye to see money in the form of the huge boy. He was the first to wring profits from the giant from Sequals, to play upon his freakishness of size, to realize that a trick nature had played could bring francs into his pocket. It was the circus that started Primo on the career that would eventually rob him of pride and self respect and place his body on the rack.

The curious, jostling throngs that crowded around the booth where Primo was on display were treated to all sorts of wild theories, mystical explanations of Carnera’s size. It was not discovered until many years later, long after Primo had been in the ring, that he was afflicted by acromegaly, a tropic disease that makes giants.

Primo hated the circus life. “It was no good,” he said. “It is no life to live. I feel foolish and I am very lonely most of the time. I am paid very little, which I do not realize at the time, and the work is hard and the conditions bad. I get very homesick many times, when I am with the circus, more than when I was a laborer.”

Under a variety of names, Carnera was billed first as a freak, then as a strong man, finally as a wrestler. He could, at 17, snatch a 350-pound weight into the air and hold it over his head. He often wrestled as many as 10 or 12 men a day, taking on all comers. In the beginning he was a poor wrestler, but it was good business for the circus when one of the town locals could best the giant.

When circus business was slow, the manager would stage a special wrestling match. He’d paste posters around the town announcing that “The Terrible Giovanni, Champion of Spain,” would be seen in an exhibition match. As Giovanni, Primo would perform against experienced mat men. He often made miserable showings, but his size pleased the crowd. He stayed with the circus three years and, toward the end, actually became a fairly competent wrestler.

Eighteen years later, in 1946, it was the things he learned about wrestling in that small-time circus that were to save him, bring him out of obscurity, give him back the self respect and the fortune that had been denied him as a fighter.

The circus, after traveling all over Europe, wound up in Paris in 1928 and disbanded. A second-rate heavyweight pug named Paul Journee, walking through a park one day, came upon Primo sprawled disconsolately on a bench. Journee marveled at his size. He sat down and began to talk to him. It was this simple action that started Primo Carnera on his fabulous ring career. Here began the blood, sweat, frame and fix that, in six short years, was to see him crowned heavyweight champion of the world.

“If I had not been broke that day,” Carnera said, “if I had not been so miserable, I do not think I would have gone with Journee to talk to this fight manager, Leon See.”

The fight game has had few characters of such clashing temperament as Leon See. He was a strange mixture of a man–at once sentimental and shrewd, tough and learned, a diminutive, kindly charlatan, who had earned a degree at Oxford, been a fighter, promoter, gambler, and referee, a hanger-out in the subterranean dives of Paris, rich one day and poor the next. From the first time he laid eyes on the shuffling giant, the tiny, energetic man had an enormous affection for him.

Carnera has nothing bad to say about Leon See. “He was shrewd, you have no idea how shrewd,” Primo said, “but we were friends. He was always my friend, even though he did wrong many times. His son is here in America now. I do not know where Leon is now. I talked to his son. It is strange,” he went on, “we meet here in the lobby of the hotel and we talk about old times. He is a fine boy.”

The bustling Frenchman, who enjoyed posing for pictures standing under Carnera’s outstretched arms, was delighted with his new charge. He believed him to be the strongest man in the world, and promptly arranged a fight for him. It was the first of many sad mistakes. The 21-year-old Primo knew nothing about boxing. He had over-developed muscles, and was slow and clumsy. Yet, within two weeks after See signed him, he was matched against Leon Sebilo, a Parisian pug of doubtful reputation. Even See, who loved Da Preem, could not resist the opportunity of making quick money.

Primo kayoed Sebilo in two rounds. Whether the fight was on the level, only See knows, and he has never told. From the moment he took Carnera into his heart, and his training camp, Leon See became a frenzied, driven man. It did not take him long to discover Primo’s weakness, which was the fact that a slight tap on the chin by a man 100 pounds lighter would send Carnera reeling. Carnera had courage. He could take blows to the body all day long, but the giant had a glass jaw and the wily Leon was quick to find that out.

The little manager worked long and frantically to teach Primo the rudiments of defense. At the same time, undoubtedly motivated by a desire to cash in, he tossed the huge Italian into the ring at every opportunity, rushing him through 13 fights in less than a year. Primo won most of them by quick knockouts, fighting in Paris, Milan, Leipzig, and Berlin.

Whether these waltzes were on the level is highly debatable, but See was wise enough never to allow his big boy to think he was anything but invincible. Some of the fights might have been square, because some of the so-called fighters who went up against Carnera, couldn’t have lasted a round with any American tank-town bum. Names like Luigi Ruggirello, Isles Epifanio, Constant Barrick, Ernst Roseman, Jack Humbeek, Marcel Nilles, to name a few, were patted over by Carnera in quick order, or as cynical French and English boxing writers put it, “to order.”

The, reputation of Leon See was far from spotless. His connections among the lower depths of Parisian life were solid and extensive. In fact, in those days, there was something of an international underworld linked to the fight game. It was not long before a coterie of mobsters from New York, U.S.A., took a trip abroad to have a look-see at this large-type character who might make them a fast buck. In less than a year’s time, the unknowing Primo was being “cut into pieces,” parts of him being sold to sharpsters who frequented the shadowy sections of America.

“It is well known,” a prominent booker of fights and wrestling matches told me, “that Leon See sold over 100 percent of Carnera before they ever left France.”

The noted sportswriter, Paul Gallico, was the first to uncover the machinations of the underworld types who were preparing to use Primo to bamboozle the public into parting with their money. Some six months after Primo started fighting, Gallico happened to wander into a smoky fight club in Paris, mildly curious about the word-of-mouth publicity that had been passing around about the giant. The place was called Salle Wagram and Primo was matched against a 174-pound powderpuff puncher named Moise Bouquillon.

One of the first mobsters to buy into Primo was also there that night. He did a slow burn when he heard about the presence of Mr. Gallico. Later he said to the sportswriter, “Boy, was that a lousy break for us that you come walking into Salle Wagram that night and see that the big guy can’t punch! Just that night you hadda be there. We could have got away with a lot more if you don’t walk in there and write stories about how he can’t punch.”

Primo won that fight, taking a 10-round decision. He went on pushing down the pushovers. The only fighter of any reputation he fought before coming to America was Young Stribling. Strib was no world-beater, but he was a fair enough boy with his dukes. The fights, one in London and one in Paris, both ended in fouls. Carnera won the first, Stribling took the second after being struck a low blow. The English scribes were rather indelicate in their descriptions of the contest, implying that both fights were as rehearsed as a Shakespearean play.

Through all of this, Carnera was kept completely in the dark. This may be hard to believe, but Leon See was with him night and day, censoring what he read and thought. Leon’s magic tongue worked triple-time, his words convincing Primo that his strength was as the strength of 10, and his punch devastating. Leon even arranged to have Gene Tunney, then visiting abroad, pose for newsreel pictures with Primo, “Europe’s challenger for the title.” As sincerely as Leon liked Primo, he couldn’t ever pass up an angle. “Tunney was very friendly to me,” Primo said. “I was just a novice then and he was very nice: I feel he was pulling for me. He said he hoped he would see me in America soon and wished me luck.”

If ever a man worked hard and sincerely to become a fighter, it was Primo Carnera. The huge, simple, gullible giant believed with all his heart and soul that he had the makings of a great champion. He believed no man alive could hurt him. He believed that his punch was dynamite and that he had mastered the rudiments of la box, as Leon See called it.

“I dreamed of going to America,” he said. “It was with me all the time, this wish, this dream. I work very hard and I was sure that I would someday soon be the champion of the world.”

Those last few days in Paris, preparing to sail forth on his conquest of the new land, were very happy ones for Primo. The 23-year-old mountain-sized boy was led across the ocean to his eventual triumphs and cruel slaughter in the spirit of the knight on the white charger. Gene Tunney just happened to be down on the dock when the boat, groaning under the weight of the huge Italian, docked. Again he wished Primo luck. The big fellow was all smiles, filled with sweetness and love toward his fellowmen and his newly chosen profession.

It is no credit to us, as Americans, that we can be duped and ballyhooed into believing anything. The very people, even the sportswise, who later sneered and smeared the giant Carnera for his simple-mindedness, for allowing himself to be so blatantly tricked and cheated, were among those who created the legend of his fistic prowess. It was late in 1929, the stock market had crashed, the world was confused and churning, when Carnera came to the United States. He was immediately hailed as “a mighty killer,” a “Neanderthal type with a tremendous punch,” “a new, giant menace on the American boxing scene.”

The lying, shameless, vicious men who pulled a gunny-sack over the eyes of the giant and the public did a masterful job of it. They were quite a collection of tawdry and dangerous individuals. There were Broadway Bill Duffy and Owney Madden, both of whom had spent time behind bars for anti-social acts of a violent nature. There were, in minor capacities, such cute characters as Mad Dog Vincent Coll (later rubbed out), Big Frenchy DeMange, Boo Boo Hoff, and other parties of odious repute. It is still considered not altogether healthy for anyone to poke his nose too deeply into some of the “deals” these charming chaps cooked up while interested in cashing in on Carnera.

The fraud started in Madison Square Garden on the night of January 24th, 1930, when Primo Carnera was sent into the ring against a built-up, fourth-rate heavy named Big Boy Peterson. The evil faces crowding around Carnera’s corner at ringside were a bit anxious about the affair, knowing that if the spectators failed to swallow the hoax, their plans would be knocked into a cocked hat. Not having anything to offer in the way of a fight, they had wisely decided to give the onlookers a “show.” It was some show.

Anyone who has ever seen Primo Carnera cannot help but be amazed by his awesome size. The powerful effect of that tremendous figure of a man, as he lumbers toward a ring, is enough to send shudders through even the most hardened fight fan who revels in bloody slaughter. Primo Carnera, coming down the aisle that night, looked like nothing human. This was a deliberate piece of staging. Followed by the tiny Leon See and other carefully picked midget-sized men, Carnera did not wear the usual fighter’s bathrobe. Instead, he was dressed in a hideous green vest, a weird, visor-type cap, and black trunks on which was embroidered the head of a wild boar.

The humorous mutterings of the press, which had implied before the fight that it was to be a phony, were disregarded and forgotten by those who witnessed the spectacle in the Garden that night. The massive figure of Carnera, the lumbering tower of might and muscle that pawed at Peterson, somehow pleased the collected gathering. The men behind the scenes knew that they were “in” and could put the show on the road.

It was a fight that deserves little attention. Peterson managed to get his jaw in front of a glove containing Primo’s pumpkin-sized hand and fell to the floor. He was counted out in the first round, undoubtedly resting comfortably on the canvas and contemplating the steaks he would be eating for the next several months. Back in the dressing room, Monsieur See was jubilantly bouncing about the room telling one and all about his fighter’s glorious future. Primo sat on the table, surrounded by the tough guys, his large, kindly brown eyes dreamy and filled with wonder. That night he proudly sent a cablegram to his parents in Sequals, telling of his triumph.

“It was the first cable ever received by anyone in my town,” he said. “It was very impressive.”

The gang bundled up their giant and began a cross-country tour, moving from state to state and leaving behind them a trail of fixed fights, intimidated and coerced pugs and managers. Working with gangsters and gamblers, and using threats and violence, they cold-bloodedly staged one outrageous swindle after another. In one year, Carnera watched 22 victims go down under his playful pushes, more frightened by what they saw outside the ring than by the big, helpless man they faced.

In Chicago, the Illinois Athletic Commission proved somewhat more determined than the New York hierarchy. After Primo cuffed Elziar Rioux to the canvas in 47 seconds of the first round, the yowls of the press were so long and loud that the fighter’s purse was held up. But the gang pulled strings and Primo was given the green light, Rioux taking the blame for a poor showing.

What Rioux knew was that it was better to do poorly and live than to tag Carnera and die. The men behind the giant were intent on cleaning up and that they did, gathering unto themselves over $700,000 on the tour. If an opponent refused to take the dive, to “talk business,” he was shoved about a little by the muscle-men. If that didn’t work, he often found himself, just before a fight, staring into the tiny, round opening of a .38 caliber weapon. Does it sound unbelievable? It happens to be the absolute truth.

In Philadelphia, a Negro heavyweight named Ace Clark walloped hell out of Carnera through the first five rounds. Just before the bell called him out for the sixth, a small, icy-faced man slid up against the ropes near his corner and said, “Look down here, Ace.” The fighter looked, saw something gleaming and metallic beneath a coat, and performed an extremely believable dive in the next 30 seconds. A Newark pug was visited in his dressing room and treated right roughly when word reached the “crowd” that he might doublecross them and put up a fight. He too melted in the first round.

Out in Oakland, California, a large, classy puncher named Bombo Chevalier was having a lot of fun belting the amazed Primo around the ring. He might have ended the string of faked victories then and there, but midway through the fight he suddenly discovered something had gone wrong with his eyes. One of his own handlers had been bought, during the course of the fight, and had rubbed his orbs with some sort of inflammatory substance. That incident smelled so foully that an investigation followed, but the gang weaseled out of it and went on to the next swindle.

Some of the fighters Carnera bowled over were not bums, but they were all made to see the light. George Godfrey, a large, fast-moving, and skillful puncher, had a terrible time losing to Primo. It was almost impossible for this boy to fight badly enough for the huge Italian even to hit him! He finally solved the dilemma by fouling Primo in the fifth round.

After the fight, several suspicious reporters came into Godfrey’s dressing room and began to ask him how hard Primo could hit. “Hit?” the large Negro grinned, “That fellow couldn’t hurt my baby sister.” The reporters began to laugh and then into the room walked several of the gentlefolk who were handling Carnera. Godfrey’s face changed. “That white boy sure has some punch,” Big George said, quickly, “I thought the house had fallen on me a couple of times there.”

It was that raw. Long before Primo Carnera became champion of the world, the Duffy crowd had given the heave-ho to Leon See. As sharp as the little Frenchman was, even he could not stomach the conniving that was part and parcel of the Carnera buildup. He could visualize the end. He knew that the “fix” could not go on forever, that someone would tag the vulnerable chin of the giant and the inevitable decline would begin.

Leon did not always play square with Primo in the matter of money. But he did try to teach him to defend himself, and he did his best to keep the big fellow from suffering physical harm. After he was ousted by the gang, See took to writing a syndicated column, exposing the fights Carnera had. He stated outright that on the few occasions when opponents could not be threatened by guns and brass knuckles, then Primo lost.

While Leon See was at Primo’s side, life was bearable for Carnera. “He was the one friend I had in America,” Primo said, “He did not always do right. He was reckless and foolish in handling my money, but he was my friend.”

Carnera saw very little of the juicy sums collected for the 80-odd fights he participated in before winning the title. In California, Leon took a chunk of Carnera’s dough and invested it in real estate, buying two homes. In Oklahoma, he sunk a pot full of cash in an oil well that was dry as dust.

“I didn’t know what he was doing,” Carnera said, shaking his head. “The banks notified me that the homes he had bought for me were no longer mine. I did not pay something or other. The mortgage, that was it. Leon bought many things for me, but I believe he was cheated.”

While Leon was with him, Primo at least had someone with whom he could talk, someone to kill the hours of loneliness. See treated him like a son, babied him, became maudlin and sentimental over the giant he knew was going to be taken away from him by the wolves. Carnera idolized the little manager. If he went out to a movie alone at night, he would scrawl a note to Leon telling him at what time he would return. Then he would rush back to the hotel to tell him all about the picture he had seen.

Shortly after Leon See was forced out of the picture, the dazed and unhappy giant was asked how he felt a manager should treat a fighter. By that time, Primo knew (or suspected) that all was not well, that he was not quite as invincible as he had been led to believe. “He who goes slow, goes surely,” he said. “He who wants to travel far, is kind to his horse.”

Carnera on the cover of the Oct. 5, 1931 Time magazine

It was after the fight against Jack Sharkey on October 12th, 1931, that Primo Carnera knew that he had been tricked and deceived, that he was not the one-punch killer that he had been led to believe since the days in Paris. It was a terrible, humiliating, cruel fact for him to face. It was much harder to take than the beating the Boston gob gave him.

No one who saw that fight in New York will ever forget the look of pain and wonder on big Primo’s face as he went down under Sharkey’s blow. It was a sharp left hook to the jaw and it dumped Carnera to the canvas with a thud that could be heard in Times Square. He sat there dumbfounded, his eyes glazed. He finally got up on his feet, but when he saw the scowling Sharkey advancing on him, he dropped to his knees, a pitiful, abject, and stunned creature.

Those who crucified him as being cowardly, who taunted him with boos and derisive cries, did not know what was going on inside the huge man. As later fights proved, he was courageous beyond belief. He could take merciless punishment. That night, it was not Sharkey from whom he was cowering. He was hiding from himself, from the realization that he was nothing but a gigantic fraud in the hands of hoodlums, that he had nothing, neither a punch nor a defense.

Sharkey almost lost that fight. When Primo sank to his knees without being hit, the sailor started to jump out of the ring, thinking the fight was finished. It would have disqualified him, but his handlers managed to restrain him. He went on to pound, jab, poke, and cut up the giant for nine more rounds. Primo took it, then tottered down the aisle, his head hanging.

After that fight, Carnera wanted to quit. He was broke, lonely, sick at heart. “It was too late, then,” he said. “They had me by the throat. They would not let me quit. Every fight was to be my last one, but it never was. I had no friends in the game, nobody I could talk to even, or ask advice. Everyone cared for the money, that’s all. I knew it, and this is a very lonely thing.”

The gang had an answer for everything. After he beat King Levinsky and Vittorio Campolo, they hustled Carnera out of the country until the stench of the upset would blow over. They pushed him into fights in London, Paris, Berlin, Milan. There was quick and easy money to be made in these places. Carnera’s string of knockouts in America could be made to look very impressive and the Sharkey thing could always be explained as a fluke.

“After Leon left,” Carnera revealed, “they did not even care whether I trained or not. I did the best I could by myself. They did not care whether I was in condition, or what I did. They just made the matches and took the money and that was all.”

Eight months in Europe and then the gang led Carnera back to the States again, arranged another tour, and fined up a bevy of such hand-me-down old-timers as Les Kennedy, Jose Santa, K.O. Christner, Jack Spence, Jim Merriott and even Big Boy Peterson again! By this time, even the public was wise to the set-ups, so the mob used a convenient ruse to ride Carnera into the fight for the title against Jack Sharkey.

On February 10th, 1933, Primo kayoed Ernie Schaaf in the 13th round of a fight at Madison Square Garden. Shortly after the fight, Schaaf died. The ugly fact is that Ernie Schaaf was a sick man before he entered the ring that night. A few months before, in Chicago, he had been terribly battered by Max Baer. He should have been in a hospital bed that night instead of a ring. It was not Primo’s ineffectual jolts that killed him, but a lax Boxing Commission.

Max Baer

The death of Ernie Schaaf was just the sort of thing that the men who had the giant in chains could use to boot him into a fight for the heavyweight title. It was just the gimmick they needed. They passed the word around that Primo’s mighty punch was responsible for Schaaf’s demise.

The incident still has painful memories for Carnera. “It was not me who did this to him,” he said. “Everyone knows now that it was not my fault. I would not do such a thing. When it happened I felt sick. I told everyone that it was not my fault.”

But the mob made use of the tragic accident–their boy was a mighty man again–and they signed him to meet Jack Sharkey for the title on June 29th, 1933, at the Long Island Garden Bowl.

The Boxing Commission closed their eyes and allowed the fight to take place. There were some very queer strings being pulled in high political circles. It was not the first time that top, national figures had been reached to pull the mob behind Carnera out of the fire. The zippy, dark-haired, fast-talking Jimmy Johnston had intervened a few months before to square Carnera with the New York Athletic Commission, going all the way up the ladder to make a pitch to Jim Farley.

The behind-the-scenes knavery was so obvious that when you study the reports of that heavyweight title fight, you sense the shame of the newsmen who were sent to cover it. Few of them came right out and called it a fake and a swindle, but all of them either felt it or knew it. Nat Fleischer, the most renowned ring expert in the country, stated in plain English that he couldn’t understand how Primo won. When I talked to him about it recently, he said, “Sharkey should have knocked him out. Carnera won that fight with an invisible punch. I don’t hold Carnera responsible though,” he went on. “He was built up by set-ups. He was a nice guy and never meant anyone any harm. He just wasn’t made to be a fighter.”

And Gallico, who had been keeping close tabs on Carnera’s ring activities ever since that night in Paris, was another who announced in clear and ringing words that nothing would ever convince him that it was an honest prizefight, contested on its merits. Paul was still feeling hot under the collar about it as late as 1938, when he wrote his Farewell to Sport.

“Sharkey’s reputation and the reputation of Fat John Buckley, his manager, were both bad,” Gallico wrote. “Both had been involved in some curious ring encounters. The reputation of the Carnera entourage by the time the Sharkey fight had come along in 1933, was notorious, and the training camps of both gladiators were simply festering with mobsters and tough guys. Duffy, Madden, etc., were spread out all over Carnera’s training quarters at Dr. Bier’s Health Farm at Pompton Lakes, New Jersey. A traveling chapter of Detroit’s famous Purple Gang hung out at Gus Wilson’s for a while during Sharkey’s rehearsals. Part of their business there was to muscle in on the concession of the fight pictures.”

Primo climbed through the ropes that night looking very unlike a confident, keyed-up challenger rarin’ to slug his way to the heavyweight championship. He looked miserable, ill-at-ease, soggy, and listless. Sharkey scowled convincingly from his corner, but the beefy John Buckley seemed uncomfortable, as though someone had been following him all day.

For five weary rounds, Sharkey scored point after point, bouncing light left hooks off the huge target that floundered around in front of him. Jack was always an in-and-outer, but at his worst, he should have been able to put Primo away in four heats. He had, some 18 months before, hardly worked up a sweat belting Carnera unmercifully for 15 rounds. On this June night, however, his punches had about as much kick in them as a wet sock swung by a ten-year-old. In the sixth round, after a mild exchange of blows, Sharkey went down as though he had been hit by Jack Dempsey.

He was counted out. Manager Buckley, making pantomimic gestures, rushed to Carnera’s corner and demanded to inspect Primo’s gloves, implying that they must have contained horseshoes or other such implements of iron. The amazed Carnera stood helplessly in his corner while this farce was being enacted. The entire scene was fragrant with an unmentionable type of odor.

It must have been a sweet night for the gamblers. The odds were in favor of Sharkey, 5-4. Everyone cleaned up. By this time, the vultures who had been cleaning the big bird through 80 fights had cut themselves in on grosses that amounted to over $2-million. And Carnera? The day after he won the Championship of the World, he had just $360 to his name.

A month after the fight, the bewildered giant filed a bankruptcy suit. He was also being hauled into the courts on a breach of promise case involving a waitress, who claimed the champ had promised her a ring and a trip down the aisle. Primo escaped to Italy for a few months of peace and attempted, among his own people in the tiny village of Sequals, to collect his wits.

In Rome, the Fascisti hailed the giant as they would a conquering hero returning from ancient wars. A match was arranged against Paulino Uzcudun, a tired old warhorse who submitted to Primo’s clumsy clouts for 15 rounds. Mussolini stuck his jaw out an inch or so further, pounded his chest, dressed Carnera in military uniform, and sent pictures to the far corners of the earth showing Primo executing the Fascist salute.

It is not to Carnera’s credit that he played ball with the Fascist hoods. But he was politically unaware and, by this time, conditioned to take orders from anyone who held the whip-hand. The element he had been dealing with in America had not been a whit more scrupulous or less brutal than the dictatorship to which he returned.

Primo did disobey Mussolini once. It is not very well known, but the massive man had an inordinate love for automobile racing. He would cram his huge frame into a tiny racing car and, with utter fearlessness, give it the gun. The belligerent Benito forbade him to race, but Primo, on the sly, entered the annual 1,000-mile Italian auto race. He didn’t have the moola for a car of his own, so he drove for the Alfa Romeo auto company and placed third.

“When the boss heard, about it,” Primo said, smiling, “he called me to Rome to see him and he gave me hell.”

When Carnera returned from Italy to America, he brought with him a little Italian banker named Luigi Soresi. How Soresi was able to chisel into a “cut” on Carnera, why the mob allowed him a share of their boy, is something that Primo, to this day, does not know. Soresi conned Carnera into believing that he would protect him. The way it turned out, he was even more ruthless than the others.

Tommy Loughran

Some of the statements Primo gave out to the press in those days were lulus. In Miami, preparing for a defense of the title against Tommy Loughran, in 1934, Carnera told reporters: “I don’t pay any attention to money and such things. I am crazy about boxing. The rest I don’t give a damn about!”

And the shifty-eyed, sharply dressed group who hovered around him managed to keep a straight face. They were having the time of their lives in Miami nightclubs, spending C notes in huge quantities, tossing lavish parties, and carrying on in a style that was imitative of Capone in his heyday. They paid absolutely no attention to their fighter’s training or condition. They set him up, in miserable quarters on one of the back-lots of the town and never even bothered to see him. Primo tried to get in shape for a week or so, then gave up and sat brooding, lonely and filled with despair. He came into the ring against Loughran some 20 pounds overweight.

Carnera is proud of the fact that he won a decision against Loughran. In a sense, he has a right to be. It was one of the few fights he is certain was on the level. Actually, the Carnera crowd knew that they were taking few chances sending their boy in against Tommy Loughran. They knew Loughran was completely honest and could not be fixed, but he was an aging, washed-up fighter. He was 32 years old, had been fighting for 15 years, and had always been a powder-puff puncher. Most of Tommy’s reputation had been made as a clever light-heavyweight. Carnera outweighed him that night by a mere 105 pounds!

Actually, the gang desperately needed one honest fight to hold up in front of the public, no matter how uneven the match. Writers like Quentin Reynolds were putting the finger on them in national magazines, stating, “Carnera is directed by very rough characters, who hover about his corner and sometimes the corner of his opponent.” The boys did not consider this a very nice way to talk about them. It hurt them right where they lived, in their pocketbooks.

So Primo leaned against Tommy Loughran for 15 rounds in Miami. He was little better as a boxer than when he had started, but Loughran was unable to hurt him, or he Loughran, and he was awarded the decision. That same year, such whirlwind pugs as Walter Neusel, Johnny Risko, and Jose Caratoli also punched out a decision over the tired Tommy. At that, Loughran managed to whack Primo a couple of times in such a manner as to make his legs wobble. Carnera landed on Tommy’s button time after time with right hand uppercuts that had more steam than the one that floored Sharkey and won him a title. Loughran barely blinked.

The characters behind Carnera might have gone on forever lining their pockets with championship gates, but law and order finally stepped in and took charge. The Roosevelt Administration had outlawed the speakeasies, and G-Men were putting the chase on Public Enemies. Mister Duffy took a trip to the jailhouse for evasion of income tax. Others in the select circle who had a piece of Carnera did not consider it quite safe to be seen in daylight and things, in Runyonesque lingo, had become very deplorable, indeed. Max Baer was clamoring for a crack at the title. The public was fed up with poor Primo, and the unhappy giant was badly in need of money. He agreed to meet Baer.

The thing that took place on the night of June 14th, 1934, in Madison Square Garden Bowl, was not a fair fight either. It was a slaughter, an indecent and pitiful thing to watch. Max Baer could hit. He made a bloody mess of the monstrous, defenseless, reeling ex-circus freak and strong man.

“I never liked Carnera before,” a rival fight manager told me. “To me, he was nothing but a big, stupid bum. But, by God, I loved and pitied the big, blind ox that night, because I never seen so much guts.”

Baer knocked Carnera down three times in the first round. He gave him a worse beating than Joe Louis later gave Max, but the giant got up and kept on taking it. At the end of the 10th frame, his face a grotesque, bruised, and bloody mask, after being knocked down in every round for a total of 13 times, Primo was still in there taking it. Baer never did beat him into unconsciousness. It would have been much more humane if he had been able to do so. The referee stopped the fight in the 11th, to the relief of everyone but Carnera. Primo was too numbed by that time to feel much of anything.

Did the gang relinquish their hold on Carnera then? They did not. There was still the possibility of wringing more blood-money out of the peaceful Italian. There were still sadistic fans who would shell out to see what they considered a monstrosity being hammered into a pulp by a mere, ordinary man. Soresi and company patched Carnera up and carted him off to South America to paw some pesos out of our unsuspecting friends south of the border. For six months Primo wallowed around rings in Argentina, Uruguay and Brazil, earning his backers still more dough.

Citizen Duffy was released from prison, and one of his first acts was to bring Primo back from South America. The boys had arranged an interesting and remunerative little fracas for their sorely battered fighter. They were throwing him into the same ring with a harmless young heavyweight out of Detroit, a certain Joe Louis. After all, the Bomber couldn’t kill the big lug, although it is doubtful if that would have made the slightest difference to the men in Primo’s corner on that memorable night.

In the first few seconds of the fight, one of Joe’s jolts completely smashed in Carnera’s mouth. Who among those who saw the fight and knew the story behind Carnera will ever forget the sight of Duffy and the boys shouting angrily into the ears of the bloody giant, shoving him out round after round to what looked like certain death?

The time was 2:32 in the sixth round when the ghastly affair was halted. What a wretched thing was dragged from the ring that night, what a mess of a man! Thus had fate dealt with the uncommon offspring of Giovanna Carnera, who had once said, softly, “Since he is our first child, I shall call him Primo.”

Here on a night in June, 1935, was the apparent end of a career that had started because a miserable, giant-boy of 12 had wandered hungrily into France in search of any work that would keep him alive, and had once listened to the words of an old prizefighter who had found him on a park bench.

If ever a man should have been through with the ring, it was Primo Carnera after the Louis debacle. But the jackals who still had him in tow never asked themselves such a humane question as, “How much is enough?” His name would still draw the suckers.

Carnera kept fighting through 1935 and into 1936. A third-rate Negro heavyweight named Leroy Haynes finally administered the coup de grace. He kayoed Carnera in three rounds at Philadelphia. The fight drew a fairly good crowd, so it was repeated just 11 days later in Brooklyn. Haynes hammered, cut, and chopped Primo for nine rounds, beating him so fiercely that one of the giant’s legs became paralyzed and he could no longer stand up to take his punishment. He was hustled from the ring to a hospital. His tormentors then released him.

Listen to Carnera’s words. “I lay in the hospital bed for five months. My whole left side was paralyzed. I was in much pain. During all this time, not one of them came to see me. Nobody came to see me. I had no friend in all the world.”

When Primo was released from the hospital, he was still limping. He hobbled up a gangplank and took a boat back to Europe. In Paris he stopped long enough to pick up a meager purse in a fight against someone called Tony Duneglio, which he lost in 10 rounds.

A week before Christmas in 1937, on a snowy night in Budapest, Primo Carnera, the former heavyweight champion of the world, was knocked out in two rounds by an unknown Hungarian heavyweight named Joseph Zupan. It was his last fight. The New York newspapers devoted a couple of lines to it.

The world of sport had written the giant off the books. It looked as though that was the way it was going to be.

Primo went back to Sequals, to the village where he was born. His parents had died, but the people of the small town still had great affection for their giant, and he for them. He built himself a house, lived simply, devoted himself to farming. He was married, in 1939, to a girl who worked in the post office in a nearby town.

After they were married, Primo and Pina planned to settle down to a peaceful life in Sequals. They had two children, a handsome, sensitive-faced boy named Umberto, now seven, and a girl, Joanna Maria, now five years old.

But Carnera’s peace was short-lived. The war began, and the Nazis moved into Italy. Primo and Pina buried most of their household furnishings in the ground. The Germans put Carnera to work with a pick and shovel, at 20 cents a day. On Carnera’s back is a deep, indented scar, fully five inches long, a wound suffered at the hands of the Germans during this time. At night he would scavenge around the countryside, trying to find food for his children.

One day a plane came in low over Primo’s house in Sequals and the family hustled to the cellar in terror. When it had gone, Primo went out into the yard and found a huge box had been dropped. “I approach it very carefully,” he said. “I poked it with a stick. I thought it might blow up. It was from you–from the Americans. It was food, all kinds, and canned milk and cigarettes and beer and almost everything. I knew then that it would soon be over.”

The GI’s finally trudged into Sequals. They shook hands with Primo, stayed in his house, took pictures of him, talked about fights and America. When the war was over, Carnera was broke, but he was no longer a lonely or hopeless man. The world had hit him with everything, but he was still standing upright and thinking of the future. There came offers from the United States. He was not completely forgotten.

At random, Primo chose the offer of a smalltime Los Angeles promoter named Harry Harris. He wrote, agreeing to come to America and work for him, providing Harris would send him enough money to make the trip. Harris called the Olympic Auditorium, owned by the matchmakers Babe McCoy, Cal Eaton, and Johnny Doyle. He got McCoy on the telephone and said, “I’ve got Primo Carnera. Are you interested?”

“Yeah?” There was a pause. “Where is he?”

“In Italy,” Harris said. “Would you put up the money to bring him over and get him started?”

McCoy talked it over with his partners. They decided they could use Primo as a referee at fights and wrestling matches, signed a deal with Harris, and sent Primo the money to come to Los Angeles. On the 1st of July, 1946, 10 years after he had left the United States a crippled and broken man, Primo was back again. He was 40 years old, but even under the careful scrutiny of the matchmakers of the Olympic, the giant looked as powerful and in as good condition as he had been before the sluggers had gone to work on him. They took him to a gym and watched, in amazement, as he wrestled playfully but skillfully with some of their grunt-and-groan boys.

“What the hell,” they said, in effect, “we don’t have to use this guy as a ref. He wrestles better than most of the beefs we’re booking.”

A month after Primo’s arrival, in August 1946, he was matched against Tommy O’Toole in the main event at the Olympic Auditorium in L.A. McCoy and Harris had not the slightest idea how Carnera would fare as a draw or as a grappler. The fact that he had looked good in a gym could mean nothing.

The night of the match, the only cheerful, confident figure was the big Preem himself. Wrestling was something he knew about. He felt he was built for it, fashioned by nature for and would not look freakish at it, the way he had always looked with those big, padded mittens on his fists.

The giant was right. The match was a sell-out. Primo won handily against the burly O’Toole. The crowd loved him. This was the beginning of one of the most amazing and ironic comebacks the annals of sport. In one year’s time, Primo Carnera, who fell harder than any prizefighter in ring history, has climbed to the very top of the wrestling business. From the Hudson Bay Territory to New Orleans, from New York to California, the Italian giant is now the biggest drawing card in professional wrestling. The grosses on Primo’s matches have gone over the million-dollar mark.

Those who come to see Carnera wrestle generally come back for his return engagements. They may come, the first time, because they expect to see a freak, or to stare at a man who was a former heavyweight boxing champion. But they discover that Carnera has more to offer than the memory of a pitiful past.

It is a wonderful sight to see Primo Carnera striding toward the ring, whether you see him in an impressive auditorium in a large city, or in a smelly, smoky, barn like structure in some of the tank towns where wrestling is staged. Once the enormous red-and-blue bathrobe is unfurled, the huge body is still an awesome thing to behold. But now, in contrast to the flabby opponents he faces, you are struck by the beautiful proportions of the giant. The skyscraper height, the massive shoulders and chest and legs, the powerful arms send a thrill rather than a shudder through the crowds who watch him.

But what is most impressive of all is the new-found dignity of the huge man. You know he understands what it is all about now. You know he feels he has found where he belongs, a place and a profession where he is no longer regarded as a freak.

In the seamy by-ways and smoke-filled auditoriums of wrestling, where a turbaned “Hindu,” a self-styled “Champion of Greece,” a bearded “Tyrolean Terror” or “Man Mountain” is commonplace, Carnera gives you the feeling that he is playing his new role as straight as his curious profession will allow.

He studiously refrains from the elaborate play-acting, the contortions, the grunts and groans and burps that are as standard with most grapplers as are the mannerisms of the burlesque “stripper.”

In the ring, Primo wears a self-deprecating smile that seems to say to his fans: “You and I know what this is all about. But what the hell–you’re having fun, and so am I, so what’s the difference?”

Primo Carnera goes for the pin against Tony Galento. © The SPORT Collection

Against Tony Galento one night in Newark, New Jersey, Carnera put on a performance that would have been ludicrous in lesser hands. Towering over his opponent, he looked as though he could pick him up with one hand and throw him into Market Street.

Instead, he crouched and stalked and clenched his huge-fingered hands and went through an elaborate ritual of holds and spills and falls that at times looked almost convincing.

The crowd booed without restraint, but the jeers were friendly: “Don’t worry, Primo! If you lose this one, you’ll win next week in Pittsburgh!” The “contest” ended in a draw. The crowd applauded and whistled and stamped and yelled, but their faces were smiling, and they seemed well pleased. They had got what they paid for–a spectacle–a monster of a man rolling on the mat like a big, good-natured bear in a sideshow.

As a private citizen, Carnera is looked upon today as a decent and honorable man.

When you walk with him through the lobby of a New York hotel, people turn and wave at him. They call “Hi, Primo!” They are not just struck by his size; in their faces are the friendliness and respect that he has needed for so many years. For Primo is one of God’s most warm and likable creatures, a man who has a deep and genuine affection for people, and who needs the same treatment in return.

With the exception of one month of vacation, Carnera has been wrestling four to six nights a week for the past year and half. He has traveled over a million miles by air and wrestled some 300 opponents. He’s lost just one match–in Montreal, when a large, rough boy named Yvon Robert punched him in the jaw. Primo whacked him back, and Yvon went down and out. Carnera was disqualified.

“Carnera is a wonderful trouper,” Al Mayer, who books him in the East, said. “He always shows up for his matches. He never disappoints a promoter. The fans love him.”

Mayer opened the books and pointed to some of the black figures that indicated how Primo had been drawing. In four appearances in New York, the gross was over $100,000; in Montreal, $64,000 for three dates; in Cleveland, Los Angeles, and Philadelphia, his single-shot dates gathered $18,000 in each city; in Detroit, $17,000 for a night; in Chicago, $16,000; and in Miami $12,000. And so it goes.

And Primo now gets his check every week, on the line. He gets a large and fair percentage of the take, and he handles the money himself. He has bought himself a $30,000 home in the fancy Westwood section of Los Angeles. It is clear this time, no mortgages.

The men now connected with Carnera are a different breed of cat from his associates in pugilism. His personal manager and closest companion is Joe (Toots) Mondt, a former heavyweight wrestling champion. The bulky, genial Toots has the face of a benign Santa Claus. His reputation in wrestling circles is spotless and his devotion for Primo is completely and wholly genuine.

“I’ve been traveling with Primo for over a year now,” Toots smiled, “and I’ll tell you that anyone who can’t get along with him must have a hole in his head. He’s become one of the best friends I’ve ever had in this world. He is a clean-living guy, an honest man, and I couldn’t ask for anyone better to handle.”

Mondt gave up a flourishing business as a promoter around Washington and Oregon to handle Primo. Toots was so impressed by Carnera, who appeared in a match Mondt promoted, that he accepted Babe McCoy’s offer to train and handle Primo. Toots is making quite a performer out of Da Preem. And Mondt is the man who can do it. He has met them all–Stanley Zybysko, John Friedberg, Jim Londos, Big Munn, and the renowned Strangler Lewis.

“When I took Primo on a year ago,” Mondt said, “I never dreamed he would do so well. After all, he was 40 years old. But age doesn’t seem to mean anything in Primo’s case. He seems to get better as he goes along.” In an easy-going, effortless, and un-phony way, Toots Mondt can sit all day long and spin yarns about his friend, Primo Carnera. He likes to tell you about the giant’s tiny appetite; how Primo, who actually eats very little, is always embarrassed by the huge portions he is served everywhere he goes.

“We have a terrible time at parties and dinners,” Mondt chuckled. “The host or hostess always gets upset because Primo does not eat much. They think he does not like their food and they never believe it when I tell them that the only time he eats a fairly average meal is at breakfast.”

“It is true,” Primo chimed in, smiling, “I do not eat much.”

It is constantly amazing to Mondt how easily Carnera makes friends and how many of them he now has. As a fighter, he was undoubtedly the loneliest figure in ring history. As a wrestler, Primo is constantly surrounded by admirers and friends. He gets innumerable invitations to parties and affairs in every city in which he appears.

Primo Carnera © The SPORT Collection BUY THIS IMAGE

“He likes people,” Mondt explained. “I never knew a man who liked to be among people so much. I can’t understand it when he tells me he was once afraid of them and lonely. Now, he is happiest when he is among people. In towns where he has not appeared before, he will strike up friendships with people in the lobby of the hotel, even with strangers he meets on the street, and invite them to our room.

“Milwaukee!” Mondt exclaimed, throwing up his hands. “He is always after me to get a match for him in Milwaukee. There are two men in the contracting business there, Andre and Bruno Bertin. Primo knew them in Sequals. They were boyhood friends of his. He gets into Milwaukee and he practically lives with those Bertin guys and their families. It is hard to get him out of the town.”

Even the fighters who slugged Carnera insensible are now included among his friends. He is like a man trying to embrace, with a bear-like hug, the whole world. Max Baer, who took the heavyweight championship away from him, who pounded him so unmercifully, is now counted as one of his pals. In Detroit a few months ago, Baer bought front row seats to watch Primo wrestle Joe Dusek.

“O ho!” Primo bellowed happily, “Max was very excited that night. When Dusek took a slug at me with fists, Max jumped up and screamed at him and took off his coat and was going to get into the ring to help me.”

Carnera looked wise. “Maybe it was a joke, maybe he was only clowning, but it shows he is for me, he likes me. Afterwards, he invited me to the nightclub where he is playing and I am in the show with him and we make jokes together. I like Max Baer. He’s a good guy.”

And old Jack Sharkey, the surly gob, another of the sluggers who pasted Primo to the deck in their first fight, has now benefited by the giant’s affection. Sharkey was hired to referee one of Primo’s matches, a tangle with Jules Strongbow. It was a very different night, financially, from the one when they met for the second time and the Boston gob got the heavy dough in losing the title while Primo wound up with a pocketful of stones. For the wrestling match, Carnera got 40 per cent of an $18,500 gate, while Sharkey got $300 for overseeing Primo’s victory.

Everything has changed for the giant from Sequals. The odds which were once so heavily stacked against him have switched. A world that had no place for him has suddenly opened up what must seem like limitless horizons. At this writing, Primo has left for Mexico, to be re-admitted to the United States under a quota and be allowed to take out the first papers that will eventually make him an American citizen.

Pina, Umberto, and Joanna Maria Carnera are on their way across the ocean, hoping to live permanently in their father’s big house in Westwood, California. “This,” Carnera said, almost reverently, “will make everything completely happy for me.”

But Toots Mondt has still another dream for the giant. He wants to make Primo Carnera the Heavyweight Wrestling Champion of the World. This is what he’s been shooting at during all the months he has been touring with Carnera back and forth across the country.

The business of being proclaimed the World’s Champion Wrestler, as Toots Mondt explained it, is a complicated set-up. There are about half a dozen men, in as many states and subject to as many rules, who claim to be the Champion of the World. Toots wants Carnera to settle it once and for all, by beating all of them. Primo will therefore have to whip Frank Sexton, who some recognize as the champion. He will have to beat Louie Thesz, the St. Louis boy who holds the National Wrestling Association title. He will also have to pin to the mat such heavies as Bill Longson, Whipper Watson of Toronto, Jim Londos, Orville Brown, Bronko Nagurski, and Roughie Silverstein, former Big Ten Champion from Illinois.

“It is my opinion that Primo can beat every one of these men,” Toots said, with a completely straight face. “If the officials are fair and honest, Primo will win all these matches. I mean to see that they are honest,” Toots concluded, “because I intend that Primo Carnera shall be the next Heavyweight Wrestling Champion of the World.”

If this happens, Carnera will be the only man in sport history who has held both titles, the championship of the world in boxing and wrestling. How much or how little the grappling title means, it is still quite a prospect for the once hopeless and crippled, bruised and life-battered giant who hobbled up a gangplank in 1936 headed for oblivion.

Not even those idealistic weavers of words who created ancient tales designed solely to point out a moral could improve the true-life ending of this story. For what has happened to the ruthless, shameless, cruel, and greedy handful of men who tricked and humiliated and bled the giant? Almost to a man, life has repaid them. Three of them are now penniless, two are in ill health, and one frequents the grimy alleys of crime, fearful for his life.

A few months ago, in a large Eastern city, one of them provided us with a thing that is rare in this modern world, a moment of poetic justice. One of these men who had held the giant in bondage for so many years, one of the elite of the once high-riding mob, approached Primo Carnera after a wrestling match and, in our own graceless, work-a-day language, he put the bite on him.

“He looked very bad,” Primo said, “but I could not find it in myself to give him money. Instead, I bought him a meal.”

EPILOGUE

Five years after buying a meal for his former tormentor, Primo Carnera realized his dream of becoming a United States citizen. He continued to wrestle through the late 1950s–winning the ‘world championship’–and also found a third career as a bit player in several movies, including On The Waterfront with Marlon Brando. Although he was not part of the cast, Carnera’s story was the thinly-veiled subject of the 1956 movie The Harder They Fall–most notable for it being Humphrey Bogart’s last film. A weakness for alcohol began to take its toll on Carnera in the 1960s and, in 1967, following a collapse brought on by diabetes and cirrhosis of the liver, he returned to his hometown of Sequals. The gentle giant passed away there on June 29, 1967 at the age of 60.

All Rights Reserved – The SPORT Collection

RELATED LINKS