By STEVE JOHNSON and GREG OLIVER

Today’s fans know him best as the patriarch of a three-generation wrestling family. But during his prime, Bob Orton lined up against everyone from Lou Thesz and Bruno Sammartino to Ed Asner, and there’s no doubt that he prided himself in giving them all they could handle.

Orton died Sunday night, July 16, in his adopted hometown of Las Vegas, a week before his 77th birthday. He had suffered a heart attack on Friday at home, and another at the hospital. “He had an eight hour surgery that gave him a 20 percent chance to survive; he did, but about 10 hours after the surgery he passed away,” Randy Orton told WWE.com.

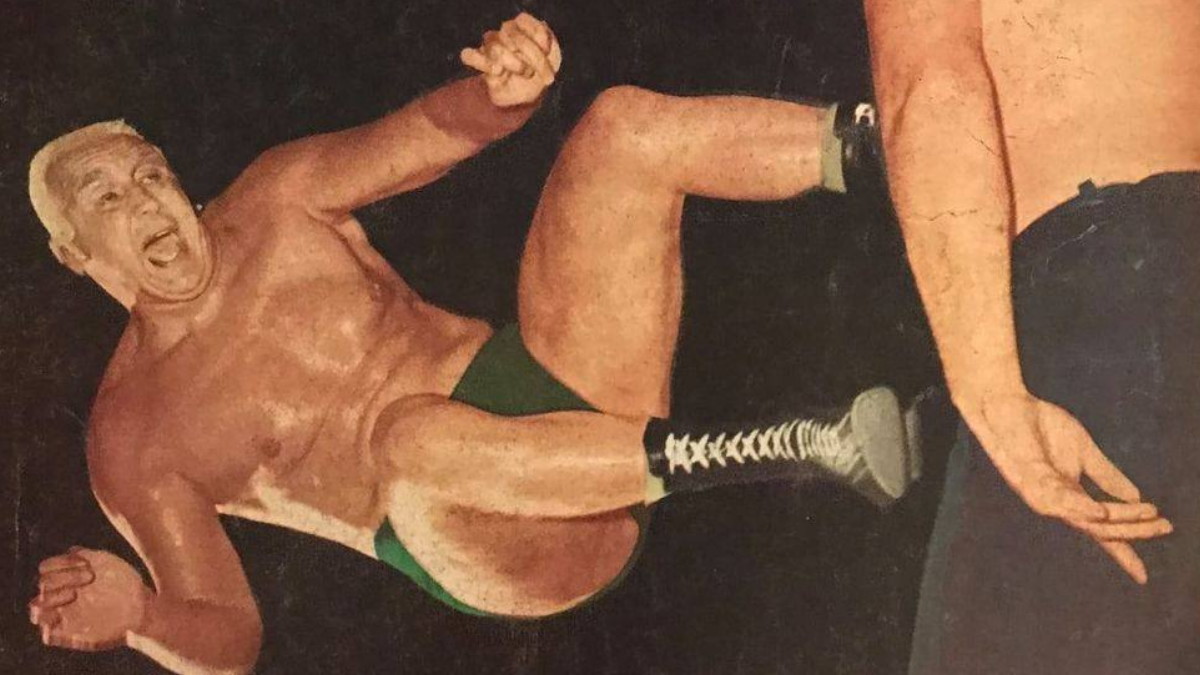

Bob Orton Sr.

While his body had been battered by his nearly 30 years in the ring — he often moved around with the aid of a wheelchair — he remained as witty and sharp as he was cantankerous. He stayed in regular contact with many of his old wrestling colleagues, and beamed with pride at the success of his grandson, Randy, in the WWE.

“His style is damned near duplicate to mine. He moves just like me, every damn thing. I didn’t teach him, I don’t know what he saw — some tapes I guess. But I think mostly it’s just him, he’s just a little like me, weird, you know? It’s wonderful to see Randy doing so well with Vince [McMahon],” Orton said in an interview just last week.

Born July 21, 1929, Orton grew up in Kansas City, Kan., where his mother, Mary, operated a popular tavern for years. He was a natural athlete at Wyandotte High School, where he graduated in 1948, and he broke into wrestling when he was 20. Though he said he didn’t realize it at the time, he was exposed to pro wrestling during a peak time in one of its hottest territories. With wrestlers like Sonny Myers and Orville Brown, whom Orton called “the greatest of all,” he said he picked up a lot just by observation.

After he turned pro, Orton was a veritable cross-country traveler, working in Florida, Georgia, upstate New York, the Midwest, Cleveland, Winnipeg and California in his first three years. In California, he hooked up with wrestler-trainer Lou Hines at the San Francisco Athletic Club, one of the three great influences on his career — Rube Wright and Boris Malenko were the others, he said. “The first time I met him, the son of a bitch looked at me and hurt me,” Orton said of Hines. “Worked out with him for a couple of years. If you’re alive after two years with that bastard, you don’t have to worry about anybody,” he said.

The hard work paid off. Orton won the Central States crown twice in the 1950s — Myers was one of his frequent opponents. But his first big national break came in the early 1960s, when he paired with Buddy Rogers to form a tag team that headed Capitol Sports cards on the East Coast against unlikely good guy teams of Johnny Valentine and Antonino Rocca, and Valentine and Argentina Apollo.

“I’d get in that ring and just look up like this,” he recalled with an upward nod of the head, “and those Puerto Ricans would be ready to kill.” Orton said he enjoyed working with Rogers, but said the NWA and WWWF champ was definitely protective of his place on the card, and even rebuffed a proposed babyface turn by Orton.

“He was kind of a strange guy anyway. He was always secretive about everything. He approached everything like, ‘Look out, look out, setup.’ But all in all, he did treat me pretty well. But he wanted to make damn sure he had that main position instead of me. We would have made all kinds of money if I had turned on him and all that,” Orton said.

Six years later, Orton returned to the WWWF as Cowboy Rocky Fitzpatrick in 1968, squaring off against Sammartino at Madison Square Garden. “Hell, people knew who I was,” he said. WWWF owner Vincent J. McMahon “just wanted a new character.”

Eddie Graham (foreground) and Bob Orton Sr. Photo courtesy the family of Gordon Solie

Orton had great runs in the Mid-Atlantic and Florida during the rest of his career. A hard-nosed, tough grappler who worked a methodical style, he laid claim to the Southern heavyweight title four times as Bob Orton and twice as the masked Zodiac, a takeoff in 1972 on the killer who terrorized California in the 1960s. (His son, Barry, would later play Zodiac in Stampede Wrestling.) He and Eddie Graham held the Florida version of the NWA world tag title in 1966 and he partnered with Mad Dog Vachon as AWA Midwest tag champs in 1968.

Little known was the fact that Orton suffered from numerous injuries throughout his career, the most serious as the result of a bad bump he took, not as a wrestler, but as a junior high school student in gym class. He landed awkwardly performing a forward roll after a trampoline bounce over a pole, and ruptured his fourth lumbar vertabra. The problem was so severe that he had to step aside from wrestling several times for treatment. Eventually, the fourth and fifth lumbar vertabrae were removed, and his spine was fused with bone from his hip. Orton also noted that he developed three serious abscesses over his right kidney during a seven-year period.

“I kept wrestling after the fusion and every damn thing. Hell, I was stupid,” he said, adding that it did alter his ring style. “I didn’t know any better and I loved it. I finally learned how to protect it, and this and that, and finally didn’t have any more trouble.”

Orton was particularly proud of the successes enjoyed by later generations of his family. Bob Orton Jr., a top-flight amateur, turned pro in 1972, and won the Florida tag team titles in 1976 with his dad, before moving on to a singles career that included a top-of-the-card match at WrestleMania I. He was elected to the WWE Hall of Fame in 2005. Barry Orton competed in the WWF, often as Barry O, and has since moved into acting and directing. Grandson Randy is at the top of the WWE roster, and his grandfather, with characteristic pride, sees his championship status as just grand.

“He’s got the whole package, doesn’t he? You talk about getting even with a lot of people; it’s sure doing it for me,” he said. When Ric Flair, in particular, won the NWA heavyweight title, “I cried for God’s sakes. Guys like Killer Kowalski that should have been the champions, or whatever. Then they get those guys. Goddamn. Women in the audience could beat them.”

Yet to confine Orton’s work to the wrestling ring was to miss an important element of his personality. Last week, he reflected on his career in an interview with SLAM! Wrestling, and told the little-known story of how he ribbed former high school teammate Ed Asner, known for his roles in movies and TV smashes such as Lou Grant and The Mary Tyler More Show.

Orton first encountered Asner at Wyandotte High School, where Asner was an all-city tackle, and Orton played left linebacker on defense and second team quarterback on offense. On the very first play at the team’s first full scrimmage in September 1946, Orton plugged a gap to stop running back Jack Farber.

“I felt my heel hit something when I got up from the pileup and Farber says, ‘Hey, wait a minute,’ and he’s down on one knee, and he points to his shin on his other leg, and my heel had split his shin open a couple inches and this deep, blood going down his shin to his shoes. Well, I felt bad, but hell, that’s football. I didn’t want to be playing the damn game anyway. I just played it because I didn’t want to be called a chicken. Hell, it’s a wonder that every damn play someone don’t end up paralyzed or something,” Orton said with a huge laugh.

Asner felt differently, though. As he got up and saw the injury to his teammate, he yelled out, “Orton, you son of a bitch!” Orton let the matter rest, thinking it was better not to pursue a fight on the field at the first scrimmage.

In 1972, Asner worked in The Wrestler, a movie that featured a number of stars from the American Wrestling Association. A few months later, AWA champion Verne Gagne slipped Asner’s phone number to Orton.

“I knew Gagne really put me over because he was always puts the wrestling over no matter what. I could tell by the way Ed was talking. So I says, “Hey, Ed, Bob Orton, Wyandotte High School, Kansas City, Kan. You remember me?” He says, “How in the hell could I ever forget you?” I said, “Oh, uh huh … OK, man, you remember that day you called me a son of a bitch on the football field?”

“Oh, well … we don’t go into that…”

“The hell we don’t,” Orton shot back. “Now movie star, president of the Screen Actors Guild and everything else,” I said, “my lady and I are out here rasslin’. If you don’t put us over and show around real good and everything, I’m going to tell everybody what you did.”

In fact, the jibe rekindled the friendship, Orton said. Asner invited Orton and his wife Rita to the set of The Mary Tyler Moore Show — giving him a playful slap after production for the heck of it — and escorted them around Hollywood. “Treated me just like a brother,” Orton remembered fondly. “We’ve stayed in touch ever since then.”

Jimmy Valiant and his wife Angel chat with Bob Orton Sr. at the Cauliflower Alley Club reunion in Las Vegas, June 8-10, 2006. Photo by Dr. Mike Lano, WReaLano@aol.com

Orton has been a regular figure at recent Cauliflower Alley Club reunions in Las Vegas. In 2004, the Orton family received special recognition for its distinguished mark in the sport. “I was always known as Bob Orton’s son, now I’m Randy’s dad,” Bob Jr. said in accepting the award.

Memorial service will be at 10 a.m. and 8 p.m. Wednesday, July 19, at Palm Mortuary, 7600 S. Eastern Ave. Donations can be made to the Alzheimer’s Association.

RELATED LINK