Terry Morgan Sr. used to get a real kick out of seeing his son’s name on posters and TV advertising. “I’m a Jr., and my father used to take a lot of flak at work all the time, because his name was on there and everybody used to think he was actually wrestling. The guys used to come in and put stuff on his locker at work with his name on it. He thought it was the best thing, he loved it.”

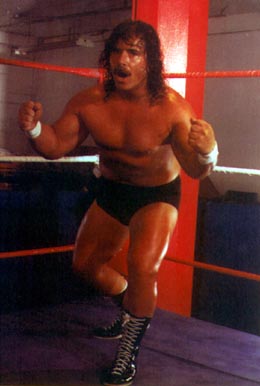

Terry Morgan

Terry Morgan (Jr.) began wrestling as a teenager at Dewey “Missing Link” Robertson’s gym in Burlington, Ontario during the late 1970s. “I was there seven days a week. I lifted weights and I trained to wrestle.” His subsequent career spanned two decades, much of which was spent in the WWE and WCW as enhancement talent. He wrestled under a number of names: Terry Morgan, Terence Storm, Tony Mancini.

Compared to a lot of journeyman wrestlers, Morgan’s entry into the business was a fairly smooth ride. He freely admits he was spoiled getting into the business. “I didn’t have to go through the small venues with 200 people, a thousand people. I was trained by some good guys that gave me the guidance for the big promotions, so I never got ripped off, never lost any pay, never had to go through stuff the way some of the other guys had to. I did okay for myself moneywise.”

After schooling with Robertson, Nick DeCarlo and Benny Lima, Morgan started wrestling before he was 20 years old. “We did mall shows, outside carnivals, an army base, and they had me go to Montreal for the ICW, that was about one or two times a month,” Morgan said.

Then the WWF called, with Vince McMahon contacting the Montreal crew. He needed guys to job for him so off I went,” recalled Morgan. “My first one was with King Kong Bundy, because I had been in the gym and was big but not too tall.”

Morgan was in the WWE just as the massive expansion of the 1980s was getting underway and recalls it fondly. “Hulk Hogan was there, Randy Savage, all the big guys were there, it was great. Vince McMahon ran everything the way it was supposed to be run, and he [always] put on a good show.”

The pace of life on the road, especially in the supercharged WWE of the ’80s, took a toll on a wrestler’s physical and mental wellbeing in a number of ways. “When I started to work for the WWE, I was on the road for two-and-a-half years, and it was hard to come home,” he said. “It was hard to train every day, and it was mentally hard. When I first got home I hated to go outside, because when you’re a star here, everybody wants to see you, wants to talk to you, get their picture taken with you. I wouldn’t leave the house for a long time, then when I finally got my stuff together I could look at it in a different light. I could go back out and enjoy myself again.”

The initial couple of matches a week grew as time went on. Morgan was also careful to avoid spending too much time around the hard-core partiers when he was working. “There’s two different kinds of people on the road. You have the guys that go to the gym, train, are in great shape, and then there’s the guys that hang out, go out drinking and do the drugs. I surrounded myself by the guys that were into fitness. Going out and having a couple of drinks after work was fine, but I would rather have gotten up in the morning and gone to the gym to work out instead of having to stay up all night partying my butt off and then go to work in the morning, because it’s a long day. There was a lot of other work that had to be done prior to our half-hour in the ring, our TV advertisements and all the other stuff.”

Still, Morgan always understood that the lure of drugs and alcohol is too strong for some wrestlers to avoid. “It’s hard, we’ve had so many guys in our business die, from painkillers, from waking up and taking stuff, going to sleep with stuff. Even myself — the first time I was ever involved in a huge match, I couldn’t sleep for three days, because every time I closed my eyes, it was like I was drunk. I felt like I was going to get sick, and I’d have to get up.”

Most of his WWF bookings came through Terry Taylor, and on the road, he became good friends with road agent Gorilla Monsoon. A cheque would come in the mail in U.S. dollars, with pay for each night he worked.

When Morgan moved on to WCW after a few years to work in a similar, occasional capacity, there were a lot of familiar faces waiting for him. “Just about everybody I worked with at the WWF went to the WCW, so the first time I went to the WCW, maybe 75% of the guys I knew already. I had grown up with these guys for five or six years, so it was really neat to see all these people I knew again. I walked out of the elevator and there were a couple of the guys right off the bat who remembered me. So that was fantastic. Business-wise WCW was a little more lax than the WWF, because you had older guys [running it] who had been wrestlers prior to that. So they would talk to you about working, they were easier with you on how to work. Terry Taylor was one of the smartest guys I ever met in my life. As a wrestler, he never got to go that far, never got the course that he should have. Talking to him really made a big difference to me, going into the ring.”

Morgan stopped wrestling about seven years ago, after a not-very-successful tour of northern Ontario. “We did a big tour up at Sudbury and North Bay for about 14 days. I was on the road with these guys and the promotion was terrible. About half of the shows were cancelled — it was the winter time, bad weather, the shows didn’t attract enough people for us guys to go in and do them. I got home and I had a black eye, I was bruised, I’d just had it. In my head and in my heart, I retired.” But he won’t rule out wrestling again completely. “If the show was big enough, I’d probably go back and do it. I mean, it’s very hard to take that out of your system. Somebody’s always going to want to promote you, and once you get that into your head, and you remember what it’s like….”

When Morgan wasn’t on the road he worked as a barber and has his own shop, located in a quiet residential district in the western end of Hamilton. “I’ve been here for 20 years and I love my business, my business is good here. I used to have somebody in here working for me when I went on the road, and gradually I stepped away from wrestling. But I had a fantastic time wrestling, I got to see all of the United States, a lot of Canada, and I loved the business. I have no complaints about my life or the business at all.”

Today, his barber shop is secondary to his family, with daughter Madeline, age five, and yet another Terry Morgan, now three years old. He doesn’t keep in touch with his old colleagues — though he did attend his first Cauliflower Alley Club reunion in June. But on his yearly trips to Florida, Morgan will often run into wrestlers in the gym.

Morgan does actually have one pet peeve about wrestling, one that’s been echoed by countless other grapplers. “It’s not fake, the wrestling business is not fake, that’s probably the biggest thing I hate to hear. I’ve had my nose broken, I’ve had all my teeth knocked out, had my legs broken, my ankles, bruised my kidneys, and you know what? I wish it was fake. I probably wouldn’t hurt as bad right now in my forties, with all the s**t that I’ve had done to me. I’ve been knocked out with a chair, I got thrown through a table, a guy hit me with a fire extinguisher and split my head open. And for somebody to come up to me and tell me it’s fake, you know what? I’ll take you outside and I’ll body-slam you. And if you get up from that, you can tell me it’s fake.”