When John Steel Hill looks in the mirror, he sees … well, John Steel Hill.

That observation might seem trivial to most people, but it is quite a welcome change for a man who has operated under more aliases than a master spy.

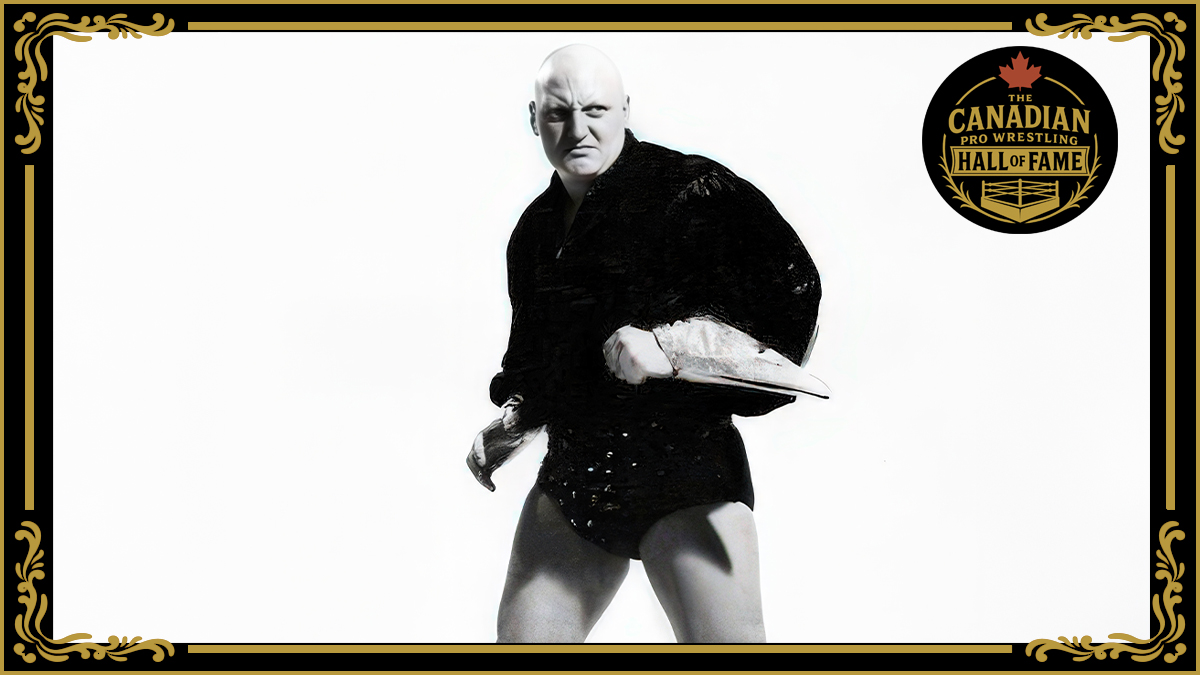

During his 25 years in the wrestling ring, Hill worked as Guy Hill, Guy Mitchell, The Assassin, The Stomper, The Destroyer, The Strangler, Mr. X, and Gentleman Jerry Valiant, among more than a dozen stage names.

That’s not a record — Hill would have to add another handful of gimmicks to catch the likes of Don Fargo — but he figures it’s sufficient to put him in the pseudonym elite.

“I would assume,” Hill said in an interview at a recent reunion of the famed Valiant Brothers tag team. “I didn’t care. I just went out and did what I had to do.”

That was characteristic of the career of the powerfully built native of Hamilton, Ontario. A reliable hand on four continents, Hill shifted personas as needed to ensure that Carolyn, his wife of more than 40 years, and his family, never wanted for anything.

In fact, despite an impressive array of titles and main events, Hill said emphatically that the greatest moments of his life were the enduring nature of his 1964 marriage and the birth of his son in Canada.

“I’ve always said to kids and other guys who are getting married, ‘Marriage is a 60-40 deal.’ Everybody always gets mad. ‘Who’s getting the 40?’ The point is you’ve both go to give 60 percent each. And I guess we’ve done that,” he said.

“You talk about sacrificing, the wives did a tremendous amount of sacrificing, but we did also. We had to sacrifice everything, always give up so much to make them happy. You talk about 40-some years in wrestling, whatever it may be, and think that every night, we’re in some bloody arena somewhere … It gets very tiresome.”

In retrospect, Hill’s commitment to a wrestling career probably was inevitable. Born in 1942, he came from a family of 11 children, which helped him to learn how to stand up for himself. And, he grew up in a city that is to wrestlers what the Dominican Republic is to baseball players — an incredible mother lode of talent.

“There were so many wrestlers walking around the city when I was a kid, I used to joke about becoming one myself,” he said. Hill engaged in some amateur wrestling as a teenager, and spent about one year training with Hamilton notables Al Spittles and Jack Wentworth. He paid his dues by working in the mail room of the Hamilton Spectator — “Executioner” Ernie Moore was a cohort there. Hill turned pro at 17, with Moore as a frequent tag team partner in southern Ontario.

Initially, he used his given name, John (or Jack Hill), but he said promoters decided that the moniker was too common and too bland. He switched to Guy Hill for a time, but that flew by the wayside when he started working in Georgia in 1961, where he thought he could make more money in the States than Canada.

Unknown to him, a newspaper story touting an upcoming card identified him as Guy Mitchell.

“I guess the mistake was made over the telephone. I tried to correct the mistake, but by that time, I had already won a match as Guy Mitchell,” he said.

From there, Hill launched his assault on the identity record book. In the Indianapolis-based World Wrestling Association, he donned a mask and teamed with fellow Canadian Joe Tomasso as The Assassins. The team won the WWA world tag team championship from Nicoli and Boris Volkoff in 1965, and held the belts for about five months.

The Assassins were notable for two reasons. First, the team established a years-long pattern wherein Mitchell would wrestle as a villain under a mask, and as a hero without one.

More importantly, it marked the first tag team break for a young manager named Bobby Heenan. It wasn’t always smooth sailing, either.

“We were going down to Nashville, Tenn. and the people were looking forward to it, and Bobby had just started and he thought he was going to make great money — you’re going back 40 years ago,” Hill said.

“We had him in Jonesboro, Ark. and we had a bit of a riot — the people were lifting up the ring and he didn’t know which way to go, so I had to grab him and pull him out. He was scared. He was ready to quit and leave, and then they tore up our car. That was common back then a lot, guys would guy their cars tore up every night. But he survived. He never wanted to go back to Jonesboro, Ark., along with a few others. But he was the first.”

At one point, Hill was Guy Heenan, kin to Bobby. Later, he had a good run as The Destroyer in Australia, capturing the IWA world title during a 1966 tour. He was back in action as a villainous Assassin, this time in singles action, as part of a long-term program in the Toronto circuit from 1968 to 1971. In July 1971, he lost a Death Match to The Sheik in front of 10,000 fans in Maple Leaf Gardens, and was unmasked as Guy Mitchell.

Oddly, at the same time he was breaking rules in Toronto, Hill was the object of fan adoration in Detroit as The Stomper, a bizarre moniker pinned on him by WWA owner Dick the Bruiser. For the record, Hill stomped a fair amount, but mostly used the sleeper as his finishing hold.

“That was Dick the Bruiser. There was somebody in the area that had the same name [of Mitchell]. Dick always had these little things that he’d come up with in his brain.”

The guise was enormously successful. Hill partnered with Ben Justice to form a championship tag team in the Detroit area. He became the centerpiece of one of the region’s hottest, non-Sheik feuds of the 1970s, when the Fabulous Kangaroos team of Al Costello and Don Kent, accompanied by manager George Cannon, “broke” his leg in a tag team bout.

Hill toured Japan while his alter ego was “recovering” stateside. “When I came back to Detroit, I was gone I guess two or three months, I was in Japan, and you walked in and feel like a matador. It was unbelievable … It was just like a matador coming into the center,” he remembered.

Justice and The Stomper regained the Detroit-based world tag titles for a second time in 1972, and the feud kept going and going.

“The whole thing was, I had to beat both Kangaroos at different times to get to George and that’s how they did this. Then when it came time to get to George, I never got to him. The Kangaroos jumped in and it started all over again. It was clever … That was a good program,” Hill said.

As Mr. X and Guy Mitchell, Hill was a top performer in western Canada from 1973 to 1975. He held one-half of the Vancouver territory’s top tag team title four times, including his stint with former NWA world champion Gene Kiniski.

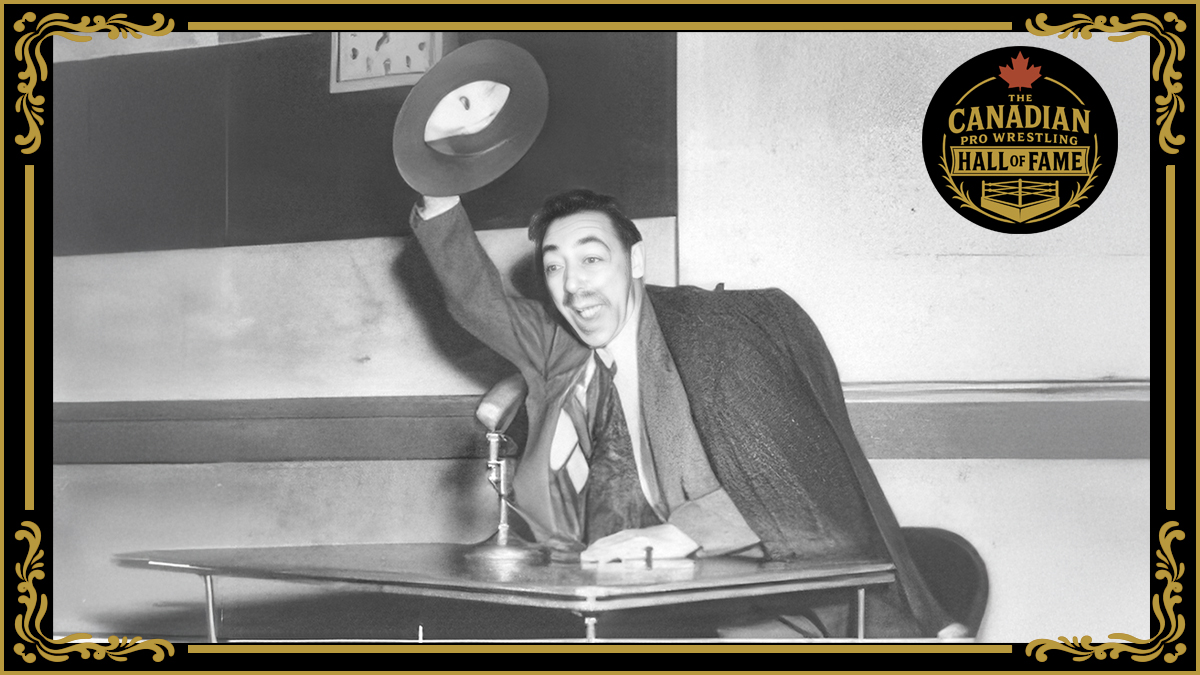

His greatest fame came as a result of a health quirk, though. In 1978, Jimmy and Johnny Valiant were preparing for an encore tour of the WWF, where they had made their mark in 1974-75 as a red-hot, heel team.

But just as the duo was re-introduced on television, Jimmy contracted hepatitis, leaving a massive hole in the federation’s plans. As Johnny (Tom Sullivan) recalled, WWF owner Vincent J. McMahon turned to him for help.

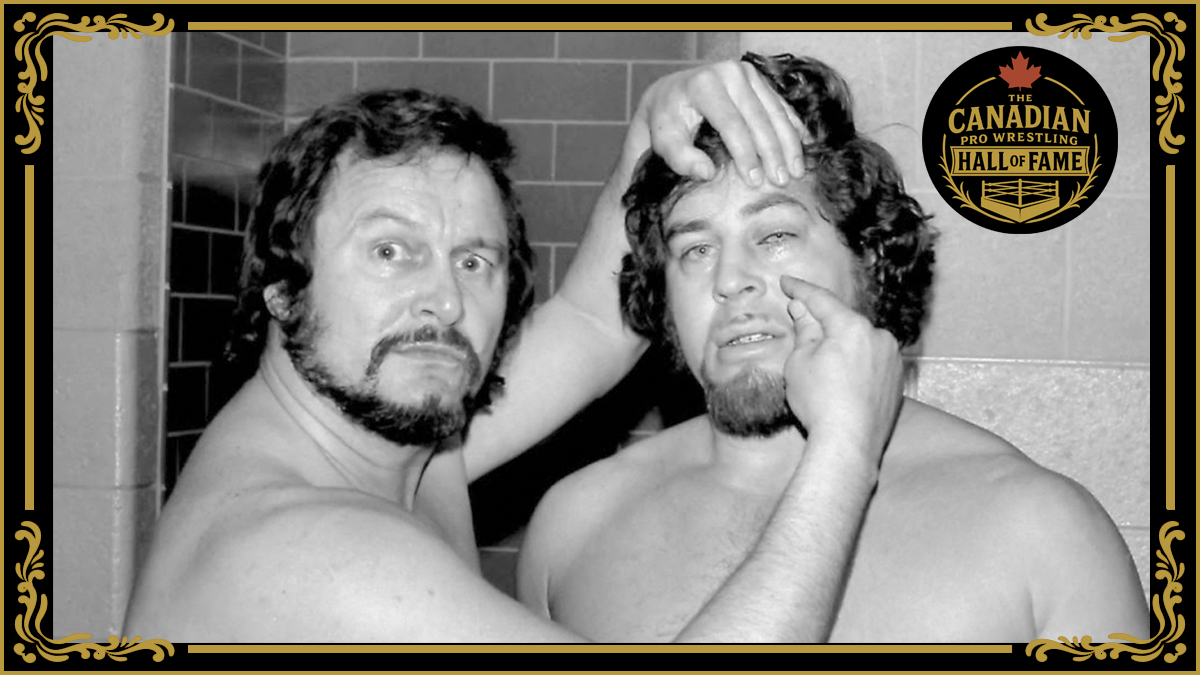

“At that point, [he] said, ‘You’re going to have to come up with somebody else. We’re going to need a third Valiant brother. I’m going to leave it up to your discretion,'” Johnny said. He had known Hill since the two had worked for Bruiser in Indianapolis, and realized his friend fit the bill — big, blond, and a “real pro’s pro.”

“So I ran him by Vince’s father and he said, ‘Bring him on in.’ I thought a while and we came up with the name, Gentleman Jerry Valiant,” Johnny said.

It didn’t take long for Jerry to make his mark, for the first time, as a hoodless heel. He started in the WWE in early 1979, and won the world tag team titles with Johnny from Tony Garea and Larry Zbyszko one month later, with outside interference from the ailing Jimmy.

Jimmy eventually recovered, presenting opportunities for six-man matches up and down the East Coast. Jerry and Johnny lost the belts to Ivan Putski and Tito Santana in October, and Jerry left at the end of the year.

Though his stay in the WWF was relatively brief, it left Hill with a bevy of memories, many of them less than pleasant. The Valiants were thoroughly despised in an era when good and evil were defined clearly in the wrestling business.

“Many times, we were in situations in this area where I said, ‘OK, I am not going to make it to the dressing room without getting stabbed.’ And I accepted that every night. That’s how you have to set your mind,” he said.

Leaving Madison Square Garden in New York, the Valiants regularly were confronted by riotous mobs that tried to overturn their transportation. That’s why Jerry said he left his family back in Indiana.

“I’d tell the cabbie, ‘You just keep going. Drive over the sidewalk, the street signs.’ And we got smart. We started taking the ambulance out. We always had to take the ambulance out, then they got wise to that,” he said.

“There was a bowling alley in Madison Square Garden. We’d go up to the elevator, across the bowling alley, run downstairs, get into to the cab, then you’d see all the people coming, and we took off.”

Hill kept the Valiant character, though, and was a two-time NWA Central States tag titlist with Roger Kirby in 1982-83. After that, he limited his involvement in wrestling and turned his attention to landscaping and contracting work, which he still does in southern Indiana.

He continues his devotion to his wife, who is recuperating from a minor stroke earlier this year. Hill maintains a low profile — his appearance at the Valiants reunion was the first time he had seen his wrestling “brothers” in a quarter-century. But his admiration for the old team is unwavering.

“We wouldn’t be here if we didn’t respect one another. I wouldn’t have lasted through the years,” he said.