WASHINGTON — You walk out the front door of the MCI Center, a glimmering, 20,000-seat artery of activity in the heart of the most powerful city in the world, turn right on F Street, and walk about 500 feet to the west.

There, inside what was once a high-ceilinged bank building, you come upon a pair of hip dance clubs, hot spots that are part of a trendy district where people meet and roar and drink into the wee hours of the morning.

It’s a two-block walk from point to point. For Dave Bautista, it’s the journey of a lifetime.

Five years ago, Bautista — the “u” has been dropped from his nom de guerre — was toiling in those nightclubs — Babylon, The Bank, and others — guarding doorways that were considerably less wide than he, working as hired muscle to put down trouble before it started.

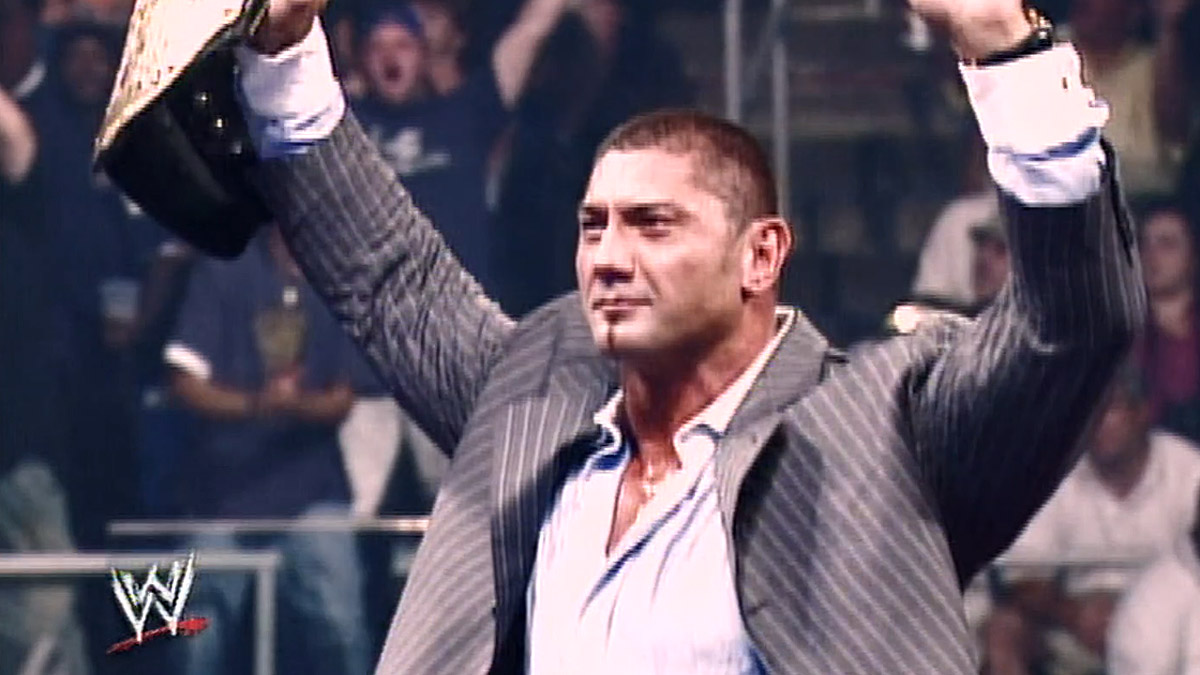

On August 21, he will enter the MCI Center to a thunder of hometown applause as he defends his World Heavyweight Championship against former titleholder JBL at SummerSlam.

At an imposing 6-foot-5 and 300 pounds, Batista is the embodiment of power and strength, a powerful successor to the lineage of WWE champions like Bruno Sammartino and Superstar Billy Graham.

But, as he reflects on his life as a bouncer, and a childhood in a struggling home just a few miles away in southeast Washington, his soft, off-camera voice quivers and cracks.

“It’s kind of emotional. It’s very emotional to come back here and have achieved so much. To know that five years ago, I was down the street …”

He composed himself and continued: “In a really short period of time, I’ve achieved a lot. It’s just coming back home, and people really appreciate and really respect what I’m doing. I came from the streets, I was a real poor kid. To me, it’s kind of like the American dream. I think people can see that and can relate to it and always back me up on it.”

Most outsiders see only the official side of Washington, with presidents and senators, three-piece suits and solemn proclamations of international consequence. But there is another side of Washington. It’s a city in which 17 percent of residents live below the poverty line and parents worry about violence in their children’s schools. And Dave Batista understands that.

He was born 36 years ago in northeast Washington at Lawrence Cambridge Hospital, a facility that no longer exists. But he lived most of his youth in the rough environment of southeast Washington, attending school at Van Ness Elementary, and living in a tough area near the U.S. Marine barracks at 8th and I Streets.

“My roots are very deep in D.C.,” he said. “I spent most of my life living in Southeast. I grew up on the streets.” Sometimes, he and his friends, who were predominantly African-American in a city that now is 60 percent African-American, would try to round up enough gear to play football.

“We didn’t have any money for equipment or anything, so we’d scrounge up stuff here and there. It was a big deal for us to go out and play a football game. I remember I had a pair of shoulder pads, and it was a big deal. Another kid had a pair of kneepads. We all had different stuff. We were so poor, we couldn’t afford much.”

When Batista was 12, his family moved to San Francisco, but he returned a few years later to live with his dad and attend Wakefield High School in suburban Virginia. It wasn’t a model childhood — occasionally, he got into minor scrapes and trouble with authorities.

For about 10 years, he worked as a bouncer at night and competitive bodybuilder by day. He got into wrestling after Road Warrior Animal and the late Curt Hennig saw him at a physique contest in Minneapolis and suggested he visit the WCW Power Plant in Atlanta.

That went nowhere, he recalled, and more than one fan has noted the connection between WCW’s demise and its inability to develop talent like Batista. When he checked with the WWE, officials directed him to Wild Samoan Afa’s camp in Pennsylvania. After starting a stint as Leviathan in Ohio Valley Wrestling in July 2000, he could finally stop checking drunken rowdies. He debuted with the WWE in 2002 as a bodyguard to D-Von Dudley.

Batista hooked up with Ric Flair, Triple H and Randy Orton as Evolution. For more than two years, the group controlled RAW, with Batista in the role of enforcer that he held at the Babylon bar, only with a lot more exposure. His rise culminated with World title victory over Triple H at WrestleMania XXI in April.

“It was a dream come true. I still have a hard time putting that into words. Just a whole wave of emotions hit me when that match was done. Before that, really that week, I really didn’t sleep much and it was just like I was walking around in a dream. Then afterwards, I was flooded with emotions and I still really can’t put into words the feeling of being on Cloud Nine.”

JBL, a villainous cross between J.R. Ewing of Dallas fame and Ted “The Million Dollar Man” DiBiase, plans to “rip apart” Batista in their no-holds-barred match at SummerSlam, But, as someone who paid years of dues as an undercard worker, he also appreciates his opponent.

“Dave is unbelievable. He’s a genetic freak; he really is,” JBL said. “You can’t have a body like that without great genetics. He’s as strong as he can be … and very popular.”

Batista quickly added that his wife, Angie, is even stronger, in her own way. For three years, she has battled ovarian cancer, carefully timing her treatments to fit in with his heavy travel schedule. Batista said last week that she is doing “very well.” On his left arm is a tattoo with “angel” in kanji script, for his wife.

The WWE is banking on Batista’s popularity to jump start sagging ratings for its Smackdown show. The behemoth moved from RAW to headline Smackdown during the company’s latest personnel two-step, which will ultimately define his reign as titleholder. With Smackdown moving to a new night (Friday) on UPN, Batista will be asked to hoist more than a 100-pound pair of dumbbells.

“It’s a lot of weight on my shoulders with Smackdown. They’re expecting a lot out of me,” he said.

“But I wanted to step up. I wanted to step up and be a leader … I’m kind of a day-by-day guy. But I’m hoping people will see me, and it’ll spark a little interest, and they’ll turn on Smackdown.”

Despite WrestleMania’s position as the sport’s signature event, SummerSlam at the MCI Center will hold a special place in Batista’s heart. Even though he has gone to other places — he lives in the suburbs of Northern Virginia — in some ways, he never left the city.

“I think I have a good lesson for D.C. humble roots, real D.C. roots. People always look at our city and they see all the politicians and everything. Really, they’re guests,” he said, pausing for emphasis.

“They’re not Washingtonians. It’s not what D.C.’s about. They’re in the political headquarters of the world. But not’s what D.C. is all about. It’s about the people, good people, proud people.”

So it’s understandable that Batista is deeply troubled by what he sees in his hometown. Just six weeks after he won the World title, Washington officials announced they would spend $30 million in the next two years for security at schools.

In part, that came in response to the fatal shootings of a 16-year-old and 17-year-old at two high schools in southeast Washington, a few blocks from where Dave Bautista played football with his friends.

“When I went to elementary school in D.C., me and my sister were the only two white kids in the school. We never had any problems. There wasn’t the violence back then. This is just a whole new plague that’s swept D.C.,” he said.

“It’s heartbreaking. Some of the things I hear — kids are getting killed for stupid things, like their shoes, or because they stepped on somebody else’s shoe, or they said the wrong thing, or they looked at somebody the wrong way and they’re getting shot for it. It makes me sick.”

Yet, Batista is not going to judge the motives of kids who get into serious trouble. Drawing on his own experiences, he knows that life on the streets causes things-bad things-to happen sometimes. Jumping to conclusions … well, issues can be more complicated than people understand, he said. So, when his whirlwind life slows a bit, whenever that might be, maybe he can help mend a small part of the troubled city.

“I don’t want to sound self-righteous and I don’t want to send a message because I don’t know where the kids’ heads are at. I don’t know what they’re going through,” he said. “I’ll make a visit. I’ll give up my time, do whatever I can … I’d like to actually go in and see them and talk to them. Then maybe I could offer a message of inspiration.

“Sports and athletics is what got me here, what made me a success. That’s a positive. If I can give back to help kids in that way, that’s something I know. That’s something I can relate to. I’d love to do that.”

For now, Batista lives just outside of Washington, convenient to Dulles International Airport, with his wife, three daughters and a complement of dogs.

But from time to time, he reminds himself of where he came from. He goes down F Street and checks out the old haunts. Now, although the clubs go by different names-Home, Platinum-they still have much of the same cast and all of the memories.

“Same clubs, still down there, still open, still running. I still go back when I can go, just to see old faces, keep up-to-date with everybody, let them know that I haven’t changed. I’m still the same person.”

And that’s not the only part of his past that he fervently embraces.

“I drive through my old neighborhood all the time and I always look at my house when I was a kid in D.C. It’s pretty much as I remember it. It’s gone downhill a little bit. It’s been kept up somewhat, as much as that area can be kept up. I always try to remind myself where I come from.”

RELATED LINK