Les Thornton, the former world junior heavyweight champion, is 70 now, and retired from pro wrestling since 1990. He’s enjoying a relaxing life in Calgary, but still owns his gym — and still gets asked all the time to help train young wrestlers.

“I’ve got a few kids that want me to train them. It’s not the time — it’s getting stuff together. I’m still trying to decide is it worth it?” he told SLAM! Wrestling. “If you can push them up and get the WWF to use them, then it’s okay. But they’ve got their own people now, training their own people, putting their own people under contract now so it’s kind of hard to get people in there.”

He can feel the 34 years of pro wrestling in his bones. “I still work out. I’ve got aches and pains and what not,” he said. “All that bumping and banging shit. The first 10 years of my life, we didn’t do that. It was all ground wrestling, so in other words, you didn’t take any of those goofy bangs and bumps. In England, you could do that.”

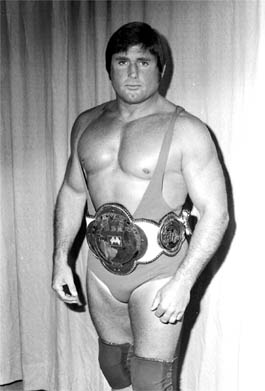

Les Thornton as the world junior heavyweight champion. Courtesy Chris Swisher

Born just outside Manchester, England, Thornton was into cricket, soccer, boxing and rugby as a youth. In the British Navy, he was an able seaman stationed in Korea, and honed his boxing skills. Thornton later played professional rugby for a dozen years before being convinced to give pro wrestling a try by an oldtimer. “I was in the YMCA one time, doing a little training, working out on the mat with the amateurs. A fellow by the name of Bomber Bates … he asked me if I wanted to turn professional, so I did.”

Thornton trained in the famed “Snake Pit” in Wigan, getting schooled in amateur and submission wrestling. He broke into the squared circle in 1957 and was soon a regular on the British and European circuits.

“What got me big in England was a fellow by the name of Bert Assirati. He was a bonecrusher, breaking everybody’s legs and stuff,” he said. “So to make a name in England, if you went in with him, then your money went up and you got your name. You were made then.”

Built like a fireplug — 215 pounds of muscle on a 5’9″ frame — Thornton quickly made a name for himself under his real name, and as Henri Pierlot and the masked Checkmate.

By the end of the ’60s, he was a veteran of rings around the world. In Sweden, they expected you to wrestle in the ring, and would whistle and boo at any pro moves – no throwing punches, for example. In Turkey, they really love their wrestling. “Even the girls have got cauliflower ears!” he half-joked, before launching into a story about falling onto an octopus.

In his native land, the occasional promoter would tell both opponents that they were going over 2 falls to 1 so the third fall would be a shoot; “There’d be a fight for the last bloody fall!”

He met Gene Kiniski in Japan, and “Canada’s Greatest Athlete” invited Thornton to his Vancouver, B.C. promotion. (Thornton completed trips to Germany and Beruit before arriving in 1970.)

Thornton soon realized that there were indeed reservations with the promoters about pushing British grapplers, and a distrust of sorts from the wrestlers themselves.

“The English people were never pushed,” he said. “You went down to the States, to be the champion there you had to do absolutely ridiculous things. …. But they always treated us good and made us money. They made us money, but didn’t put us on top a lot. That tells you something, doesn’t it. That’s the business.”

He brings up the great Billy Robinson as the perfect example. “You don’t read about the English because the Americans never built the English up. Bill Robinson was the best wrestler in the world, but it never moved him up. He got a bad name because he wouldn’t work for some.”

The exception was Stu Hart’s Stampede Wrestling promotion, where Thornton first made it big, trading the North American title with Big John Quinn. “Stu was good. You know why? Because we were good for his territory-we were good workers and wrestlers. Stu brought people who could wrestle. It was good for Stu because the style got over here. Americans didn’t like our style of fighting. They were frightened of it.”

Off-and-on for five years, Thornton was in a tag team with Tony Charles, who was from Wales. “Tony was a great worker, great wrestler. There’s a fellow, he boxed and wrestler in the Commonwealth Games,” Thornton said. “We flew into Alabama a couple of times just to put somebody over on TV because we were coming off Georgia TV. And we went tag team into Amarillo, and into Texas. In fact, we were the tag team champions there in Amarillo … and in Georgia. Then we split up. I went single all around and he lived in Florida.”

Thornton spent two years living in Australia and New Zealand. “That was a good circuit in them days. You could do Korea, you could go to Japan three times a year, you could go to Manilla in the Philippines, into Australia and New Zealand, then up into Singapore. That was a good run if you wanted to be away all the time,” he said. “You could make a good living doing that. A lot of people, like Americans, don’t like being abroad. They don’t like the change, where the Europeans did. They’d think nothing of jumping on a plane and going. The Canadians the same. But the Americans just didn’t like it.”

By 1980, Thornton was making runs at the NWA’s World Junior title, eventually claiming it by forfeit in March 1980 after being unable to overcome champ Ron Starr in the ring or in the boardroom. “The only reason that I got that World Light Heavyweight Championship was because I took it. I got sick of getting messed around in Oklahoma by Leroy [McGuirk] …” he explained, trailing off into memory. “They gave [Starr] the belt, brought him up and he wouldn’t drop the belt to me. … he ran away with the belt. Then I got the Junior Heavyweight belt and I kept it.”

From 1980 to 1982, Thornton was a four-time champ, losing the title to Jerry Stubbs, Terry Taylor and Jerry Brisco for short spells, before going down to Tiger Mask (Satoru Sayama) in May 1982 in Japan.

He shared some thoughts on those opponents:

- On Jerry Brisco: “I worked with Jack, and I worked with Jerry. I had the belt and we worked all over, went all over the Caribbean with Jerry. The match was so good, they made us a lot of money down there.”

- On Terry Taylor: “He was only a kid … I had the world belt when I went into North Carolina. They’d built him up there, so I went in there. Then he was in Tennessee, they built him up there, in Nashville. Good looking kid. … Nice kid. When I used to go into Nashville, I slept at his place a couple of times. … Nice kid, good worker, a good, clean-looking fella. A good worker.”

- On Tiger Mask: “I went all around and put up with him.” Was he as good as they said? “No. You had to feed him. You know what I’m talking about, the business. He had four holds, four big moves, and you had to feed him. Even as the champion, I had to still do it to make him look good. He did all the flying over the top rope.”

Taylor is thankful today for the influence that Thornton had on his career. “He could have really resented the 25-year-old kid across the ring from him, and probably had every reason to resent me, but he didn’t,” Terry Taylor explained in a guest column about Thornton written for SLAM! Wrestling. “Les treated me with respect and taught me a lot.”

A short while later, Thornton caught on with the expanding WWF and was one of their key men on the international scene. “Vince [McMahon] made me three or four grand a week, and I wasn’t doing much,” he chuckled. Into his early fifties, he was given the reigns of a WWF tour of the Middle East, including Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Kuwait. “We went to Saudi Arabia, and it was a seven-week tour in Saudi Arabia in ’84 or ’85,” he said. “I ran the shows in Saudi Arabia and Australia and in Kuwait and Cairo for the WWF. I wrestled and ran the shows for them. When I came back, I couldn’t keep up with them. My wife had come back here [to Calgary], so when I was 50, I came here and opened a gym.”

He laughed at the memories from the tour of the Middle East. A regular user of chewing tobacco at the time, Thornton had an ally in Jimmy “Superfly” Snuka, who also partook of “snuff.”

“[Snuka] always had snuff. I had run out of snuff. It’s the middle of the day and we’re all playing cards. ‘Jimmy, give us a pinch, will ya? I’ve run out of snuff.’ He said, ‘Okay.’ After about a week, I couldn’t get snuff there. Finally, he said, ‘Listen, Les, I bought you some snuff from downtown.’ I didn’t even look at the can, and I stuck it in my mouth. It tasted bloody awful. ‘Jimmy, where’d you get that from?’ They all laughed at me. It was camel shit. He’d picked up some camel shit and put it in a can.”

Yet, despite the fondness in his voice as he recalls old friends, Thornton explained that he severed his past wrestling life quite on purpose. “When I cut myself clear, I cut myself clear. When I finished, I finished, and I didn’t bother with anybody.”

The one person in Calgary he sees regularly is “Cowboy” Dan Kroffat. “I see him all the time and I believe he is living quite comfortably here in calgary with his wife,” said Kroffat. “He looks good and is taking care of himself.”

RELATED LINKS

- Feb 3, 2019: Les Thornton dead at 84

- Terry Taylor column: Les Thornton – What you DIDN’T know!